Resisting the Temptation of Growth at the County Level

by Daniel Giles

Across the USA, a battle for the souls of rural counties is being waged. The battle is fought not in major news outlets, but in local government meetings and the opinion columns of local newspapers. Despite the lack of national coverage, the cumulative outcome of these localized conflicts will change the American landscape for generations to come.

This monumental battle is between those fighting for growth—or “development” as some use interchangeably—and those who strive to conserve the current character of counties. I should note the important distinction in ecological economics between quantitative “growth” (as measured with GDP) and qualitative “development,” connoting a general societal betterment (regardless of GDP). However, there is a lot of wiggle room with these terms, and in the context of rural counties, “growth” and “development” look like the same bulldozer tearing through picturesque landscapes to make way for businesses and housing projects.

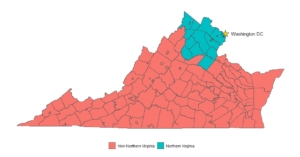

In Northern Virginia, on the western periphery of Washington, DC, county and local governments are preoccupied with the battle nearly non-stop. While the two sides engage in short-term skirmishes, the pressure to grow intensifies with every passing day, and so do the stakes. While the prospect of higher tax revenues and new community assets may seem tempting to politicians, growth is a one-way road to suburbanization.

Population Growth: The Catalyst

The ultimate source of this conflict is the rapidly increasing population. Since 2010, the population of Northern Virginia has grown 12.4 percent due to the economic opportunities and cultural attractions of the “DMV” area. The regional population has burst the seams of DC-adjacent locales such as Arlington, Alexandria, Fairfax, and Loudoun. Suburbanization is rampant. The counties closest to the nation’s capital have welcomed growth bulldozer-style, while the relatively rural counties beyond this radius simply haven’t had the infrastructure to accommodate the ravenous housing demand. But now the growth machine has begun invading these once-rural areas, foisting a “housing supply” and suburbanization.

Northern Virginia, or NOVA, comprises eleven counties on the western periphery of Washington, DC.

The next tier of counties to the west—Warren, Culpepper, Rappahannock, and Page—are facing imminent threats of growth. Retirees who made their fortunes in Washington DC feel the innate human desire, “biophilia” as E.O. Wilson called it, to enjoy a life in nature. Wanting to escape the congestion of the city and the cultural shortcomings of the suburbs, many venerable veterans of life view these rural counties as their own vestiges of paradise. They often find that the main barrier to their biophilic dream is a lack of housing. (Their biophilia is seldom strong enough for long-term tent camping.)

Increasing demand in these rural counties pushes home and land prices relentlessly upward. As property values increase, the pressures mount for farmers, cattle growers, and woodlanders to sell their lands to developers. Rappahannock County, with a recent population count of 7,348, has seen skyrocketing property values over the last decade. The Home Value Index increased 29 percent from 2012 to 2021. As the pressure to grow turns into new construction, the county lies at a critical political crossroads.

Rappahannock County: Preserving the Rich Agricultural History

Rappahannock County lies about 90 minutes southwest of Washington DC. It’s a low-density county relying primarily upon agriculture, tourism, and timber for revenue, with small pockets of developed areas dotting the landscape. Shenandoah National Park, partially overlapping the county, attracts millions of visitors every year, essentially all of whom wish to enjoy the agricultural aesthetic and uncluttered countryside.

Conservation easements have played a critical role in protecting Rappahannock’s land and ecosystems. (CC BY-ND 2.0, NRCS Oregon)

This relatively pristine paradise faces several economic challenges such as an aging population, insufficient broadband access, and job shortages. These problems motivate growthers, who argue that bulldozer development (but with “bulldozer” remaining implicit) would attract new families and increase tax revenues. However, plenty of pushback is evident throughout “the Rapp,” too, with several measures limiting the scope of development. For example, the Farmland Preservation Program incentivizes farmers not to sell or subdivide their land. The county acquires development rights via conservation easements donated by farmers, who retain all other property rights including agricultural production.

As for non-agricultural land, “open-space easements” have spared many parcels from the bulldozer. Landowners receive substantial tax breaks to donate such easements, most of which are intended to be permanent. In Rappahannock, the primary body accepting open-space easements is the Virginia Outdoors Foundation, which, as of 2020, holds easements on 31,885 acres of Rappahannock land. Meanwhile, landowners are still allowed to practice land management activities such as timber management, trail maintenance, and outdoor recreation. Approximately 20 percent of the land in Rappahannock County is under easement.

In addition to these and other types of easements and deed restrictions, Rappahannock County adheres to a maximum development density of one dwelling per 25 acres. That means, for example, that only properties of 50+ acres may be split into two developable parcels. This restriction is one of the most systemic woodland-preserving measures imaginable east of Appalachia. However, it is only as durable as the county’s Comprehensive Plan, which is reviewed every 15 years and is always subject to amendment, given enough political pressure in or upon the county government.

Similarly, while it’s true that easements “run with the land” and most are classified as “permanent,” the constant pressure of growth jeopardizes their sanctity. Courts may be unwilling to uphold conservation easements in some instances, and the status of an easement may change according to the doctrine of changed conditions.

It Takes a Village to Stay a Village

The few villages in the county, or “designated development areas,” are also protected from the bulldozer to some degree. For example, growth is restricted to one dwelling on parcels of less than five acres. This restriction fends off the long-reaching arm of DC’s suburbanizing influence and rapid population growth.

“Bulldozer” development threatens to tarnish the well-kept landscapes of rural regions. (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, Virginia Department of Transportation)

In the recently updated Comprehensive Plan, the Board of Supervisors and Planning Commission stuck with specific policies and goals for protecting the natural beauty of the Rapp and keeping villages as villages; albeit somewhat larger villages. The plan’s principles and polices protect “fragile ecosystems” and specific resources such as soil, water, air, scenery, and even “night skies.” This reveals the local government’s commitment to stopping widespread growth from consuming the county.

By prioritizing conservation over profit and growth, Rappahannock is, in many ways, nearing a steady state economy. Though there are still provisions for growth and development, the plan specifically prohibits strip malls and residential strips along county roadways. Commercial growth is confined to villages, and even those developments are limited. The final principle in the county’s Comprehensive Plan exemplifies steady statesmanship and citizenship at multiple levels:

Promote the philosophy that land is a finite resource and not a commodity, that all citizens are stewards of the land, and that the use and quality of the land are of prime importance to each present and future citizen as well as to the Commonwealth, the nation, and the world.

While Rappahannock County has proven itself a strong defender of its natural landscape and resources, the county has made several concessions to developers. Pressures from pro-growth citizens have pushed the Board of Supervisors and the Planning Commission to approve certain projects. For example, Rush River Commons was recently approved by the Washington Town Council for the construction of commercial offices, a food pantry, and rental units. Critics argue that approving the commons is a step onto the slippery slope of growth and eventual suburbanization. Supporters, however, extol the potential tax revenues and affordable housing.

The “affordable housing” label, however, is a suspected “Trojan horse” for developers seeking to conquer new areas. Furthermore, it establishes a certain level of commitment to growth beyond mere housing. Additional housing obliges governments to the installation and maintenance of infrastructure such as roads, schools, and utilities.

Steady-State Policies: The Bottom Line

The fact remains that unrelenting suburbanization and growth isn’t sustainable. If left unchecked, the rural character of many exurban counties will be lost forever. Ecological and economic factors aside, humans possess an innate appreciation for the outdoors and relish the comforts of nature; we are happy in bucolic settings. As city populations grow, more city dwellers will seek refuge in the countryside. Even counties not directly bordering urban areas must prepare to face the incoming wave of demand. Historically, Rappahannock has proven to be an excellent example to county politicians, governments, and citizens who find themselves experiencing similar pressures.

Despite Rappahannock’s continued efforts to preserve land and natural resources, however, it’s important to note the chinks in its armor. While easements and zoning laws provide some protection from eager developers, these measures can be fallible and volatile. To resist the temptations of growth, county citizens must embrace an unwavering dedication to conservation and pass that dedication down to subsequent generations.

If steady staters actively participate in local and county governments, we stand a greater chance of not only winning battles against pro-growth factions, but eventually winning the war for the soul of rural America.

Daniel Giles was the Fall 2021 economic policy intern and a senior Economics major at American University.

Daniel Giles was the Fall 2021 economic policy intern and a senior Economics major at American University.

"General Audience with Pope Francis" by Catholic Church (England and Wales) is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

"General Audience with Pope Francis" by Catholic Church (England and Wales) is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Unfortunately, these infrastructure funds are going to produce an explosion of growth. They should use the funds just to repair water systems, existing roads, and move people out of floodplains — but I’m hearing of a lot of plans to build new stuff — mainly housing.