Steady-State Origins in Sauk County

By Dave Rollo

The Driftless Area of Wisconsin (Corey Coyle, Wikimedia Commons).

As the setting for Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac, Sauk County, Wisconsin, holds a special place within the pantheon of environmental literature. Leopold’s writings on ecology and forestry brought an understanding of land repair and remediation to academic and general audiences. It is difficult to imagine the fields of wildlife biology, soil conservation, or restoration ecology without Leopold’s contribution.

Likewise, the moral basis for the environmental movement in later decades owes its origins in part to Leopold’s land ethic. Leopold articulated an eco-centric morality that placed humans as “plain member[s] and citizen[s] of the land community” rather than its “conquerors.”

Sauk County straddles the eastern edge of the “Driftless Area,” a region that “escaped” the Pleistocene glaciers. This unique geological history helps to explain the area’s trademark topography and ecology. The county is home to the Wisconsin Dells, erosion-carved sandstone cliffs along the Wisconsin River, and the Baraboo Hills, outcrops of some of the oldest rock in the country.

The Driftless Area harbors some of the most ancient plant life in the Midwest. Sandy soils and a continental climate support dry prairies that are particularly vulnerable to damage by agricultural development. It was in northern Sauk County that Leopold purchased 150 acres of degraded farmland, built a small cabin (“The Shack” of Almanac fame), and worked with his family to repair the land by planting trees and restoring prairie soils.

Sauk County is working to extend Leopold’s legacy of recognizing humanity’s place in the wider web of life. This recognition is integral to ecological and steady-state economics. It also presents a microcosm of the challenges we face as we struggle to recognize limits and live within them.

Farmland Under Threat

Over 75 percent of Sauk County is occupied by farmland. A mixture of cropland, woodland, and pastures constitute the primary land covers. Almost 65 percent of farms are under 180 acres in size, with 95 percent family owned.

Yet, the American Farmland Trust (AFT), a national organization dedicated to preserving farmland against development and sprawl, reports that Sauk County is the fourth-most likely in the state to suffer from runaway sprawl (defined as the conversion of open space to low-density housing). AFT estimates Wisconsin lost nearly a quarter of a million acres of agricultural land between 2001 and 2016.

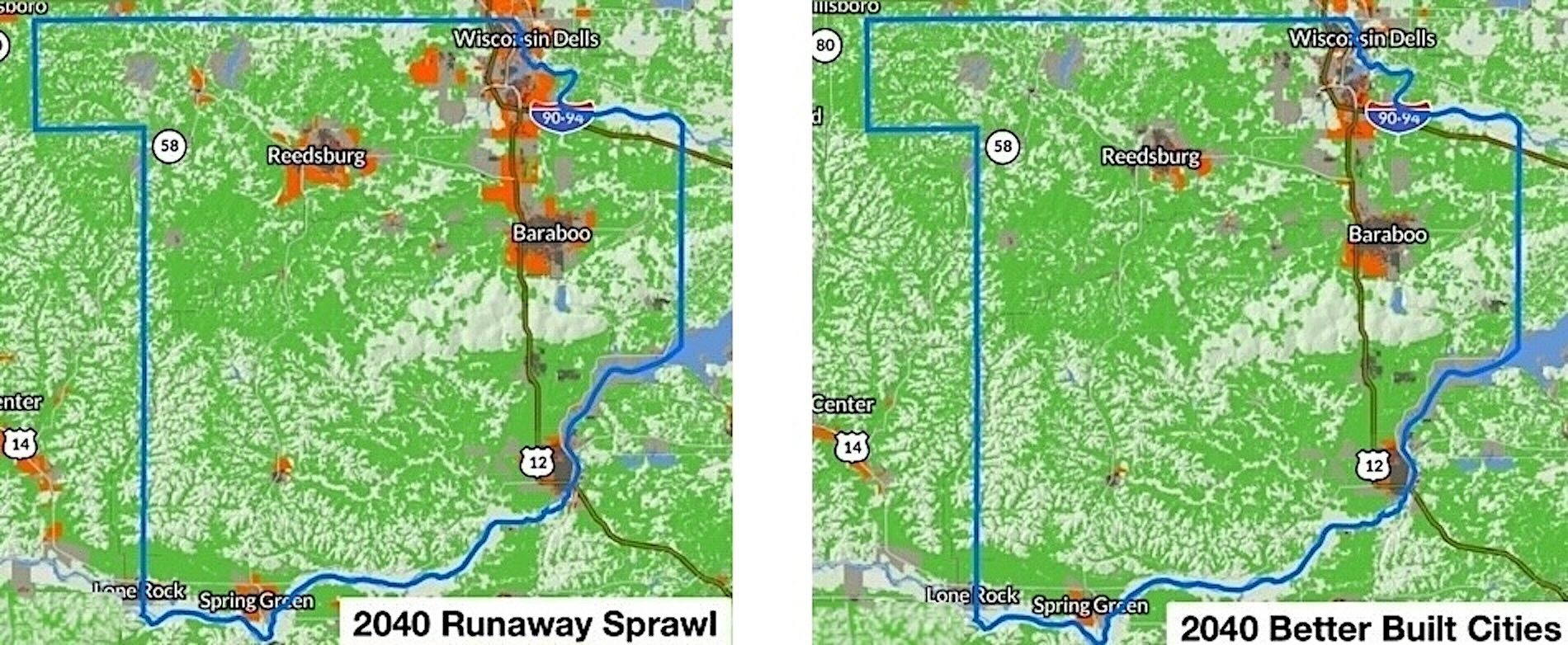

AFT analysis of farmland conversion in Sauk County under a Runaway Sprawl vs. a Better Built Cities scenario (American Farmland Trust, Farms under Threat 2040).

Furthermore, AFT projects that over half a million acres will be converted to development by 2040. Through its scenario simulations of business-as-usual and runaway sprawl, the ATF has estimated that the county could lose from 12,000 to 16,300 acres of farmland to residential housing by 2040.

Flanking Sauk County to the southeast is Dane County, the second most populated county in the state. It is also the fastest growing–by a staggering 32 percent in twenty years. This growth has generated sprawl and influenced development on its periphery. Bill Berry, an award-winning Wisconsin writer, has long tracked this trend. The “influx of [commuters] and their abodes in Sauk County,” Berry noted in our recent conversation, “is threatening Sauk County’s agricultural land and natural attributes, such as viewscapes of the Wisconsin River.”

Preservation through Local Land Policy

Recognition of development pressures has prompted Sauk County to take steps to preserve their farmland. ATF has created a consortium of organizations, both public and private, known as the National Agricultural Land Network (NALN). Within NALN, “policymakers and land-use planners promote compact development and reduce sprawl, saving irreplaceable farmland and ranchland from conversion.”

Sauk County is a member of NALN. So is the Driftless Area Conservancy (DAC), a land trust dedicated to protecting the unique ecological region by land acquisition and subsequent conservation. The DAC has protected more than 7500 acres in the Driftless Region of Wisconsin, including 1,126 acres in Sauk County.

Sauk County’s website describes their commitment to integrate conservation, recreation, planning, and zoning to protect farmland. The county has participated in efforts to increase biodiversity through native plant restoration and plant sales to the public. It has also worked with towns such as Woodland, Freedom, Winfield, Excelsior, LaSalle and Reedsburg on their comprehensive plans to limit sprawl.

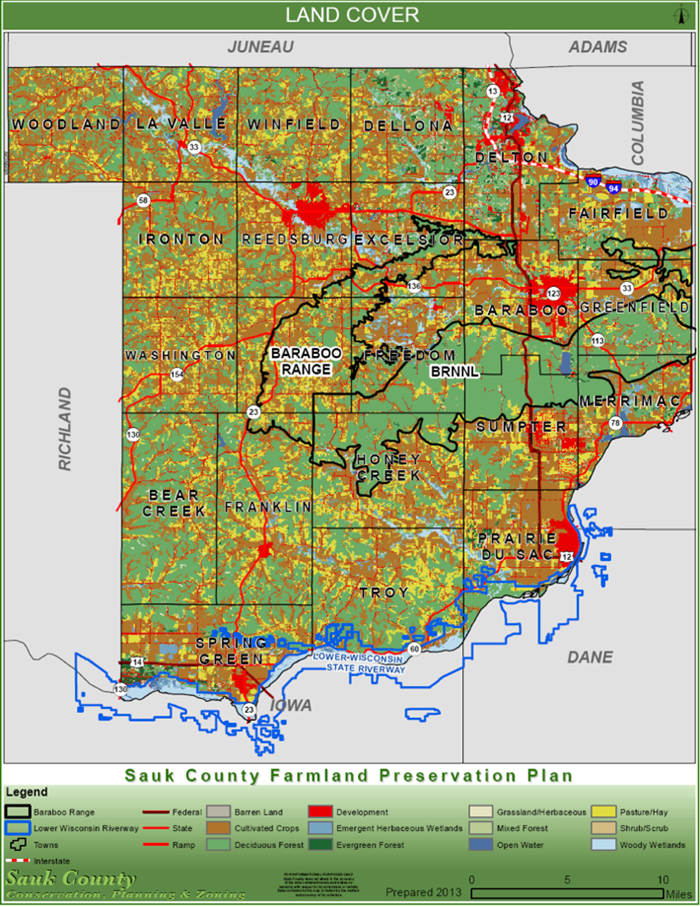

Sauk County is also updating its Farmland Preservation Plan. The planning process is open for public input. The plan includes a thorough geospatial analysis of the county. It considers conditions such as slope, vegetative cover, soils, and groundwater.

The plan will also implement several policy tools for maintaining the rural character of the county. This includes the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), which provides incentives to property owners to set aside vulnerable or marginal lands. The Board of Supervisors also instituted EAZs–Exclusive Agricultural Zoning Districts–to protect farmland. Furthermore, the county administers the Planned Rural Development Program, which establishes a limit of one housing unit per 35 acres in designated areas.

The Farmland Preservation Plan notes that about eight percent of county land is currently developed (commercial and residential). A further eight percent is designated as “undeveloped.” Tools such as Planned Unit Developments are available to direct concentrated development while preserving larger intact areas.

The Sauk County Farmland Preservation Plan evaluates land cover with precision – essential for planners to evaluate future land uses (Sauk County Farmland Preservation Plan, p.12).

The county has also created incentives to preserve its agricultural heritage. In conjunction with the Sauk County Extension of the University of Wisconsin, it has created programs to develop and diversify local farming by focusing on agrotourism. Currently, some 35 farms produce retail items for consumers, and the county is home to seven farmer’s markets.

Agrotourism demonstrates a growing desire for people to reconnect with farming. A notable agrotourism site is the Sauk County Farm, a 19th century asylum for the poor, mentally ill, and disabled. Today, the 566-acre farm serves partly as a historic site and partly as a center for development and education of sustainable and regenerative farm practices.

The County Farm Master Plan is guided by a reverence for local history. One of preservation sites is a cemetery, with the aim of “chronicling the people and events that have converged here.” The master plan also expresses a commitment, “through demonstration and research, to adopt conservation and resilient agricultural practices that improve soil health, promote biodiversity, wildlife, increase profitability, and protect water quality for the creation of resilient farms and communities.”

Seventy-five years after Leopold began his work on land repair and remediation, these efforts taken together constitute a cogent commitment to Leopold’s land ethic.

An Active Tradition of Conservation

Sauk County and neighboring Columbia County to the east includes the Baraboo Range National Natural Landmark consisting of some 53,000 acres. This designation has been a catalyst for land protection efforts. Among these is Baxter’s Hollow, the state’s largest nature preserve, located at the heart of the Baraboo Range. Here, the Nature Conservancy owns and manages almost 10,000 acres of forest habitat.

With the Baraboo Region containing so many unique natural features, it’s no surprise that the area has been the focus of coordinated conservation groups. Curt Meine, a conservation biologist and Leopold’s biographer, told me about this “remarkable constellation of groups, including the Savanna Institute, the Nature Conservancy, the Baraboo Range Preservation Association, the Driftless Area Land Conservancy, and the International Crane Foundation, Friends of the Lower Wisconsin Riverway, The Prairie Enthusiasts, the Wormfarm Institute, and the Aldo Leopold Foundation that together form a robust culture of community-based conservation.” The members of these groups share a bioregional identity and work to build consensus at the community level. Meine explains that “this bottom-up approach, with deep roots here in our area, relies on local community education and activism.” The approach has led to many successes of land preservation and restoration in Sauk and neighboring counties.

Badger Army Ammunition Plant Before (General Services Administration, Wikimedia Commons) and After (Badger Ammunition Plant Facebook page)

One of the most prominent conservation efforts in the Baraboo region involves the remediation of the former Badger Army Ammunition Plant, an enormous ammunitions manufacturing and testing site that was decommissioned in 1997. The 7,354-acre site is the focus of a 30-year effort to restore oak savanna and prairie and provide conservation-oriented educational, recreational, and agricultural opportunities. Through a process coordinated by Sauk County, the Badger Lands are now in the hands of three main landowners: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, USDA Dairy Forage Research Center (DFRC), and Ho-Chunk Nation. Over the last twenty years, the massive complex of 1400 buildings formerly devoted to manufacturing propellants for lethal weapons has been largely transformed.

Meanwhile, the land transfer of 1550 acres of the site to the Ho-Chunk Nation marked the first instance of land being returned to Native people by the U.S. Department of Defense. The restoration of prairie on the Sacred Earth “Maa Wákącąk” in the Ho-Chunk tongue) is aligned with the Ho-Chunk constitution, which observes the “Rights of Nature” (a legal provision that they were the first to incorporate and is now adopted by four other tribes). The Land Ethic and Rights of Nature concepts are clearly complementary and harmonious. The convergence of Leopold’s influence and indigenous cultural traditions forms the basis for community-based conservation efforts in Sauk County and beyond.

The Enduring and Expanding Land Ethic

Sunrise over Les Cheneaux Islands, which Leopold explored with family and friends as a young man (Kate ter Haar, Flickr)

The influence of Leopold now extends globally. The Aldo Leopold Foundation, itself active in land preservation and restoration, continues developing and extending his vision. Curt Meine, who serves as Senior Fellow at the Foundation, describes the “organizational DNA” of the process that brought about the land transfer and restoration of the Badger Lands. “We knew that we could never come to a shared vision without first defining our shared values,” says Meine. Exploring and deriving those values through consensus at the start of the process provided direction for collective decision-making. The shared framework functions “as a kind of filter,” according to Meine, to ensure that all perspectives are honored.

At its core, the steady-state perspective requires a more holistic sense of our place in nature–our extended community. “Steady statesmanship” is analogous to Leopold’s land ethic, which invites us to reclaim our place within the biosphere. It is also congruent with indigenous Americans’ reverence for nature.

Adopting the policy of a steady state economy by Sauk or any other county will require broad agreement on shared values. Or, as the Leopold Foundation puts it, “a moral code of conduct that stems from these interconnected caring relationships.” Shared values of care for each other, posterity, and for the myriad of non-human members of our community.

In the foreword to A Sand County Almanac, Leopold lamented, “Like winds and sunsets, wild things were taken for granted until progress began to do away with them. Now we face the question whether a still higher ‘standard of living’ is worth its cost in things natural, wild, and free.” Leopold understood that an economics uncoupled from ecological systems would ultimately harm the basis of human flourishing. In the ensuing 75 years, we have continued unabated on the path of perpetual economic growth. Now we observe the consequences of our narrow view of “progress.” But, in the same way that Leopold worked tirelessly to restore the damaged land under his stewardship, we can remediate economics to harmonize with limits to growth.

Dave Rollo is a Policy Specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

This beautiful article helps me “see” a territory that I once visited without really seeing. It’s good to have this example of how to stop sprawl and defend the rights of nature, with an array of bottom-up committments. Better built cities will need to be denser cities to prevent the spill-out, and hopefully, sites for agro-tourism can be reached by bicycle.

My family owned land in the Baraboo Hills from 1975-2014, now 288 acres sold to The Nature Conservancy. So my happy life includes living more than half of the Sand County Almanac chapters. The quartzite rock lays on the surface of parts of the Baraboo Range, so it was never plowed. TNC made its first Wisconsin purchase in the early 1960s when Orie Loucks, an Ecologist, took a hike and discovered a beautiful “northern remnant” plant community in one of the hollows. That community, an ice age holdout, is almost 100% gone now due to climate change and airshed logging. So preservation can fail in a warming world. I’d also mention that one reason the preservationists got to parts of Sauk County before developers was an amazing anaesthesiologist named Kindschi who lived in a trailer park, drove an old VW bug, and donated most of his salary to TNC land acquisition. It was cheap then. Leopold demonstrated the possibility of ecosystem restoration.

Shared values of care for each other, reinforced within interconnected caring relationships delivering a moral code of conduct.

Forgive me for shuffling a few of the key words. For me steadystatesmanship will come about from a cultural shift more so than from writing and enforcing policies. (That of itself is important as it helps frame the problem and focuses attention). If we get to a place where we all follow a code of conduct to do no harm our job is done.

The journey to achieving a cultural code of conduct is one of interconnected caring relationships within which we are nurtured and encouraged to do the right thing for our shared environment. Relationships the fabric of the solution, rely on known reputations. Without a framework of personal reputations being known and being accessible the fabric of the solution shall unravel.

In days of old cooperating locals knew one another, took responsibility of their reputation by helping one another, and during hardship cooperated for survival. It’s this loss of known reputation; in anonymous modern populations, that has unravelled the fabric of the framework of relationships required for our shared values of care to deliver that all important code of conduct. The solution lies in the tech in our hands. Apps to track monitor and share our reputation on indivisual environmental impact. Apps to direct our purchases onto not for profit not for harm coops. Apps to direct surpluses to environmental social and peacemaking demands.

This is the sort of thing that gives me hope, thank you.

It occurs to me, looking at the before and after pictures of the old ammunition plant, that more and more when we see a beautiful natural area the way to describe it may be less “it is untouched” and more “we made it that way, it was a choice.” Even if we humans did not literally till the soil and do replanting, it can be a significant choice to simply stop messing with an area, remove the worst things we have done, and let the biome find its own way.