Steering Away from a Car-Centric Society

by Mai Nguyen

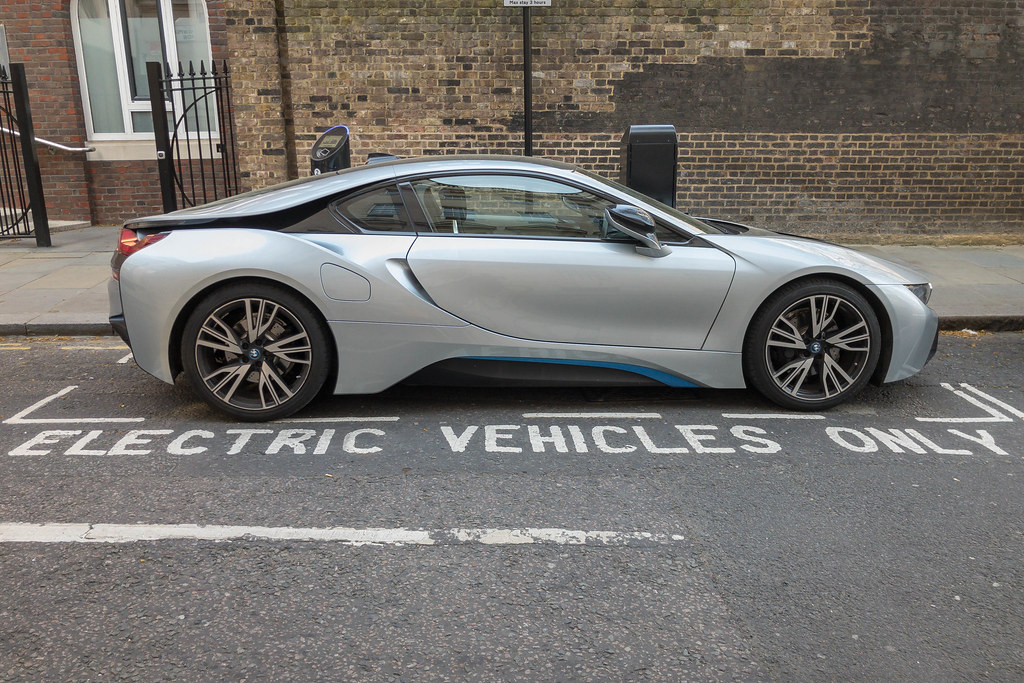

Our car-centric society is in a jam. (CC BY 2.0, Oran Viriyincy)

Learning to drive scared me as a teenager. There was something terrifying about controlling a two-ton hunk of metal, and my drivers’ education teacher didn’t help by showing a graphic slideshow of injuries we could expect from a brutal car accident. This didn’t bother me much once I moved to the city; with buses, the metro, and bike or scooter shares, there are plenty of other ways to get around. However, you’ll be hard-pressed to find these same options outside the city.

Cars are ubiquitous in the USA, with 286.9 million registered vehicles on the streets in 2020. That’s almost 300 million gas tanks to fill. The EPA reported that the transportation sector accounted for 29 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions in 2019. Now, coming out (we hope) of the COVID pandemic, we’re seeing more traffic again with attendant emissions.

Some people are eagerly replacing their gas-powered cars with new, “green” electric vehicles. The intentions are a good sign, but we can’t “get sustainable” simply by exchanging some of the energy we consume.

How Bad Are Cars?

Cars are massive machines that require heaps of resources, from building the vehicles to fueling them for the road. The average vehicle requires 900kg of steel and 39 different plastics and polymers. A single tire requires about seven gallons of oil for its production. The aluminum content per vehicle is also steadily increasing, projected to reach 505 lbs in 2025.

Manufacturing is also immensely energy-intensive and complex. Stages of car manufacturing include extracting ores, transporting raw materials and components from around the world, and assembling the vehicle. Though each of these steps emit plenty of CO2, it can be difficult to put an exact figure on car-production emissions. Carbon footprint researcher Mike Berners-Lee breaks it down in How Bad Are Bananas? The Carbon Footprint of Everything, finding that the carbon footprint of manufacturing a car ranges from 6–35 metric tons.

And the environmental cost doesn’t stop there. It’s no secret that fuel consumption contributes to air pollution, but a 2018 study found that, globally, passenger road travel accounted for 45.1 percent of global CO2 emissions, or nearly six times as much as passenger air travel (8.1 percent). Americans used a grand total of 123 billion gallons of motor gasoline in 2020, corresponding with 56 percent of transportation sector emissions.

It’s Electric!

The ubiquity of gas-guzzling personal vehicles can’t be a part of a sustainable future. For some, the solution seems obvious: electrify vehicles to remove the problems that come from gas-power. Tesla kicked off its precedent-setting electric vehicle (EV) line in 2008, and today car companies like General Motors and Honda are edging into the competition. (Ironically, GM could’ve led the EV revolution as early as the 90s with their wildly popular EV1 if they hadn’t killed the model for profiting less than their gas-guzzling counterparts.)

Are EVs driving us to a sustainable future, or are they another guise for green growth? (CC BY 2.0, marcoverch)

EV innovations do, in fact, look promising. Though not exactly carbon-neutral, EVs emit significantly less emissions than gas-powered cars, and they can handle just as much daily travel. EVs don’t run on empty, though. Depending on how your local power is generated, charging EVs can produce carbon emissions, and a worldwide shift to EVs would only exacerbate the global power demand. While it is generally accepted that emissions over the lifetime of an EV may be lower than a gas-powered car, the construction of EVs emits substantially more than the construction of traditional internal combustion vehicles. Specifically, a 2017 study found that the manufacturing of parts and assembly of EVs resulted in approximately 37 percent more emissions per vehicle than that of combustion vehicles.

Even though EV sales are picking up fast, we can’t bank on them and other “green” alternatives to solve limits to growth without a plan to fully transition away from fossil fuels and reduce consumption. Take the trendy plant-based alternatives filling shelves at grocery stores, for instance. Despite its massive carbon footprint, the U.S. meat market still dominates its plant-based competitors by almost $160 billion, and we’re simply “gifted” with more choices when we shop. The development of eBooks was similarly predicted to overhaul the publishing industry, but print books still outsell eBooks four-to-one.

Even if we all switched to EVs, we’d be exploiting yet another fuel source: lithium, the rechargeable battery’s key material. In 2021, global extraction of lithium was about 100,000 metric tons, about a 20 percent jump from 2020 levels. A worldwide switch to EVs would entail a 500-fold expansion of EV-battery manufacturing capacity. With the new mining boom, lithium and precious metal mining will simply replace (some) oil extraction.

The environment around South American deposits would be hit especially hard, bringing perils like wind drift of toxic chemical residue from the mines. This not only endangers the ecosystems along the Andes mountains—where the continent’s largest deposit is located—but threatens the livelihoods of farmers.

Chasing Us off the Streets

The problem with cars extends beyond their immediate environmental impact. We must examine why we find it so difficult to rid ourselves of them. Today’s suburban sprawl and congested highways didn’t come as a result of innovation for the masses; it’s more like the aftermath of an auto-industry takeover. Roads were once public spaces made for the people. Pedestrians freely crossed roadways without designated walkways and children played in the open space, while streetcars and railways catered to commuters and travelers.

Robert S. Kretshmar (Executive Secretary of AAA’s Massachusetts Division), Commissioner Thomas F. Carty (Boston Traffic Department), and Mayor John F. Collins celebrate jaywalking legislation. (CC BY 2.0, Boston City Archives)

It all changed with the mass production of cars in the 1910s. Over the next two decades the public was outraged at the rise of car-related fatalities, most of which involved children. A battle for the roads ensued between the masses and the auto industry. Unfortunately for the masses, car companies held sway.

A 1923 Cincinnati ordinance was proposed to limit auto speeds to 25 mph, but car companies killed the proposal—despite the 42,000 petitioners backing the plan—with a racist ad campaign mocking the city and rousing car owners. Other methods to overpower pedestrians included a slew of anti-pedestrian laws, indoctrinating children to stay out of the streets, and shaming jaywalkers.

The campaign for cars cuffed another rival, too: urban railways. Public transit has always been a key connector between low-income communities and thriving cities. It remains a major aspect of social mobility. But in the 1920s, car drivers were allowed over streetcar tracks, disrupting routes and making it nearly impossible for efficient streetcar operations. This drove transit passengers to purchase personal vehicles, further crowding the roads.

GM and other auto and fossil fuel companies bought up railways spanning 46 transit networks, only to dismantle them immediately. And while this isn’t the only reason why trolleys have fallen from grace in the USA, trolley companies were convicted of monopoly in 1949.

With the road cleared of obstacles, the auto industry set out to sell more cars. With the help of designer Norman Bel Geddes, GM debuted Futurama, a diorama portraying a car-centric future dreamed up by the company, at the New York World’s Fair in 1939 and introduced millions of visitors to something closely resembling today’s America. GM proposed a future centered around the convenience of the personal vehicle, complete with a massive interstate freeway system, suburban sprawl, and the extinction of public transportation.

The masses were sold on a car-centric America, and in 1956 President Eisenhower, with the help of Secretary of Defense Charles Wilson (who also happened to be GM’s president), leveled entire city neighborhoods to make room for highways. Minorities and low-income families comprised an overwhelming cohort of these communities, and they’ve been hit hardest by the environmental effects of “urban renewal” and the widened divide from their wealthy suburban counterparts.

Our Future Without a Map

Transportation in a car-centric society is far from sustainable or equitable. Gas-powered cars have a history of ravaging communities, and the growth of EVs won’t take us the distance. But we still need to get around, so what can we do?

Auto and fossil fuel industries fought hard in the past for political influence, but we can still take back our future. We are not fated to bumper-to-bumper traffic for the rest of our lives, and we can recenter our cities and towns around the people.

In a steady state economy, communities are walkable, bikeable, and personable. (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, UrbanGrammar)

One thing we can do is improve public transit. Access to public transportation is the key to an equitable future, but the system is in constant danger of underfunding. U.S. rail systems are far behind places like Japan, where trains are so convenient that car ownership is on the decline. Japan’s car ownership hit a low of 0.96 vehicles per household this year, while U.S. numbers have been creeping past three per household.

Fortunately, U.S. cities like Los Angeles and Indianapolis are upgrading their public transportation. Los Angeles has spent five years and $80 million on infrastructural changes to put the first electric metro bus line on the road. Meanwhile, Indianapolis is being transformed by the expansive Red Line electric bus system. These cities have shown us that commuters will jump at the chance to use public transit over personal vehicles.

Not only do our communities need access to better public transportation, but we need to foster pedestrian and cyclist lifestyles. Since 2016, Barcelona saw a 25 percent drop in pollution around the Sant Antoni market after experimenting with “superblocks,” nine-block grids of cyclist and pedestrian-first zones. Children there have room to play now, and walking and biking has increased.

In the Horta neighborhood superblock, 60 percent of survey respondents said they had become more comfortable walking on the streets and that accessibility had improved. People within the Poblenou superblock reported that the reduction in noise pollution resulted in more tranquility, improved sleep, increased social interaction, and overall improved mental wellbeing. One study estimated that widespread execution of superblocks could prevent almost 700 deaths annually.

Taking the roads back from auto and fossil fuel industries will be difficult. We‘ll have to re-envision the world around us; a world without the destructive congestion of cars. Our spaces need to be just that, our spaces, instead of streets and parking lots, dealerships, gas stations, auto parts stores, and repair shops. These profound structural and sociological changes will occur not by incentivizing the “greener” electric alternative, but by disincentivizing car culture altogether.

Widely-adopted free public transportation would be a huge step in connecting communities and promoting social mobility. We need to demand of our governments sustainable transportation for the people; that is, the expansion of our electric public transportation webs. Cars should be increasingly marginalized.

A carless society is one that is walkable, bikeable, and accessible for people with disabilities. Urban planners should prioritize the safety and mobility of the people, not cater to the automotive and oil industries. They should help us achieve a kinder, carless culture.

Mai Nguyen is the spring 2022 editorial intern at CASSE, and a junior at George Washington University.

Mai Nguyen is the spring 2022 editorial intern at CASSE, and a junior at George Washington University.

Nice article covering a lot of bases. However, I don’t agree with some of your statements. First, GM would never had led the EV revolution with the EV-1, it had lead acid batteries and terrible range. Did it show promise as a publicity stunt, yes, but it wasn’t until Tesla came on the scene that there was ever a serious BEV. If you go check your figures you’ll see GM is basically doing nothing and will unlikely ever catch Tesla (something like 450 EVs in Q1 while Tesla was 400k), if GM is even in business in 5 years. All of the major ICE car manufacturers have been doing everything they can to delay the switch to EVs, and spend literally billions on advertising and other tactics to hurt Tesla and other EV manufacturers. Regarding the Lithium, there are a lot of sources even here in the US that are showing up now that we are looking. Even Tesla thinks LFP batteries are the way forward as they use cheaper and more available materials. They are also very recyclable, so once cars are converted to electric, there won’t be a big need to dig up more raw materials as recycling is much more efficient and cost effective. Finally, I charge my EV with solar power, and as I live in a remote area, there are no other options, too far and dangerous to ride a bike (not to mention long winters). As a cyclist for over 60 years, I agree that cities and especially rural and suburban areas need better access for bikes, and have fought for this for years. Nothing against city folks but I prefer the natural setting and peace and quiet of the countryside. There is also a new trend, e-bikes and scooters which will soon be ubiquitous. I’m all for steady state economics, but until that change happens, I’d rather have EVs on the road than ICE cars, and I really don’t agree that EVs are greenwashing or promoting growth. Hybrids are however a big greenwashing ploy.

Agree with previous commenter that ev providers are not greenwashers, However an opportunity is bring missed in that older low range evs are being scrapped due to their initially low battery range, degrading with use, and the cars quickly becoming impractical. A big example of this is the Nissan Leaf. Low mileage older cars no longer ‘economically’ viable. Current profit hungry manufacturers not stepping up to provide a viable upgrade battery option, More profit to sell a whole new car around that fresh battery than repurpose a perfectly viable existing car. Is this built in obsolescence? In time as batteries degrade consumers will likely have to buy a new car to get access to the best batteries.This leaves these ‘green’ cars, with their environmental cost of manufacture, possibly doing more harm than good for the environment. Until such times as cooperatively owned manufacturers dominate or social enterprises get mass support and become dominate across all markets, the profit 1st system will put people and environment 2nd.

This article covers a lot of territory, and I wish every American would know this history. No objection to people in rural areas using a car, with no other choice, and Jacob’s comment on e-cars makes sense. That said, most people live in cities. Even if e-cars had no environmental issues, the sedentary lifestyle around car-centric urban-suburban life has become a serious public health problem. When someone gets in a car to buy a loaf of bread, the fuel being used is powering a 2-ton hunk of metal & plastics, not the much lighter human being. To me this seems like an absurd detour in human evolution.