A Not-So-Nobel Prize for Growth Economists

by Brian Czech

How ironic for the Washington Post to opine “Earth may have no tomorrow” and, two pages later, offer up the mini-bios of William Nordhaus and Paul Romer, described as Nobel Prize winners.

Without more rigorous news coverage, few indeed will know that Nordhaus and Romer are epitomes of neoclassical economics, that 20th century occupation isolated from the realities of natural science. Nordhaus and Romer may deserve their prizes for economic modeling, but each gets an F in advanced sustainability.

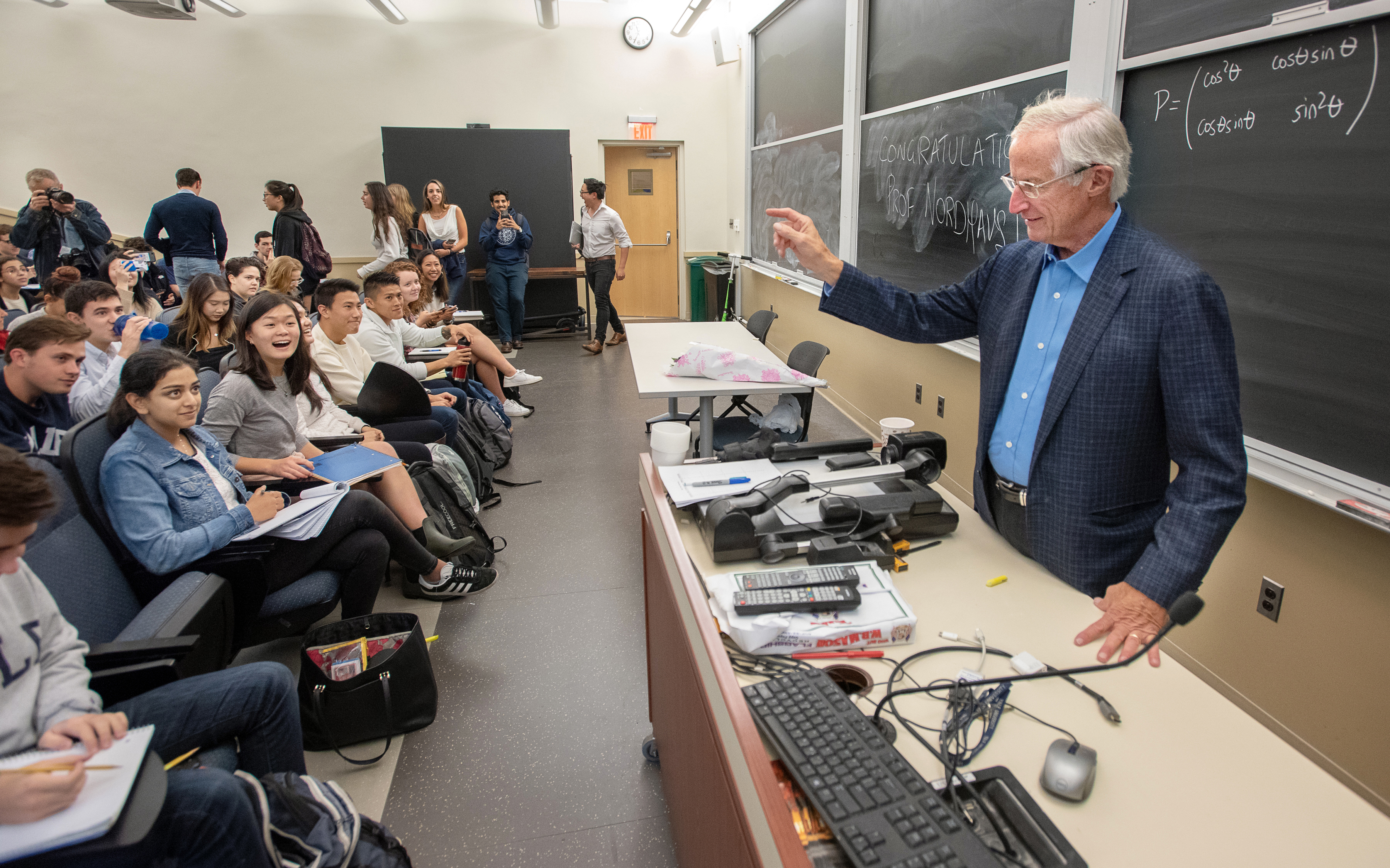

William Nordhaus shaping vulnerable minds in his Yale classroom – Oct. 8, 2018. (Photo credit: Yale/ ©Mara Lavitt)

Nordhaus won his prize (actually the “Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel”— not the Nobel Prize per se) for his mastery of mathematical modeling. He applied his skills to carbon taxes for lowering greenhouse gas emissions. All along he prescribed economic growth – the key driver in greenhouse gas emissions—as the way to afford such taxes!

In 1991 Nordhaus uttered one of the most iconic sentences in the history of unsustainability: “Agriculture, the part of the economy that is sensitive to climate change, accounts for just 3% of national output. That means that there is no way to get a very large effect on the US economy” (Science, September 14, 1991, p. 1206). Think about that. He must have set a graveyard’s worth of classical economists (Adam Smith, David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill…) to rolling. They’d be rolling in laughter if the folly of Nordhaus wasn’t so dangerous.

No follow-up should be needed to expose the ludicrous nature of Nordhaus’s statement, but just in case: Agriculture is the very foundation of the economy. No agriculture, no anything else. Think about it. Any hit on agriculture—whether from climate change, bad luck, or stupid policies—has a magnified effect on the entire, integrated economy. Nordhaus’s “3%” statement was a classic case of ivory-tower cluelessness.

Romer, meanwhile, deserves some credit for his elegant theory of “endogenous technological change,” which took the work of Robert Solow (the father of economic growth theory) to the next level by describing in nuanced detail how R&D leads to technological progress. That said, there has never been a bigger forest missed for so many trees. For him, all that mattered was capital and labor; he said nothing about land, natural resources, or the environment.

Some readers may recall Julian Simon, the ultimate Pollyanna who claimed in the 1980s (and I paraphrase after thoroughly reviewing his 813 page Ultimate Resource II during my post-doc studies), “Sure, there are environmental problems caused by growth, but the more people we have, the more brains we have to solve the problems. Therefore, the more people we have the better, without limit forever.” Romer’s work amounted to a highly nuanced repetition of Simon’s self-christened “grand theory.”

Romer said in a nutshell: We have capital and labor. Part of the labor force is devoted to research and development (R&D). As limits arise, we get over them with more R&D. So we need ever more people, with ever more devoted to R&D, to keep raising the bar for GDP.

Too many trees for seeing the forest?

For Romer, it was as if ideas alone could overcome water shortages, biodiversity loss, mineral depletion, soil erosion, pollution, and climate change. As if ideas could be perpetually borne out of human minds struggling in a degrading environment, a warming climate, and an imperiled agricultural base (not to mention a crowded, noisy, and stressed out society). Romer was like a cook thinking up recipes with no idea where the ingredients would come from.

A generation and then some of economists and business students have been led to the exceedingly dangerous myth that there is no limit to either population or economic growth. Nordhaus and Romer have done as much as anyone to lead them into such a fallacy. Yet politicians and publics heed their advice, while the media regurgitates their fallacious notions.

Does Earth have “no tomorrow,” as the Washington Post wondered? One thing is for sure: Any hope for a happy tomorrow on Earth means rejecting the neoclassical economics of today. Even when such economics wins the “Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel.”

Brian Czech is the founder and executive director of the Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy. He is the author of three books, as well as more than 50 academic journal articles.

Brian Czech is the founder and executive director of the Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy. He is the author of three books, as well as more than 50 academic journal articles.

“Sure, there are environmental problems caused by growth, but the more people we have, the more brains we have to solve the problems. Therefore, the more people we have the better, without limit forever.” Of course one could also draw the opposite conclusion!

I predict that no media pundits, no students or colleagues of Nordhaus or Romer, much less the Professors themselves, will make the slightest attempt to rebut Brian Czech’s criticisms. Please prove me wrong! A real debate on basics would be a breath of fresh air from Nobelandia.

Thank you, Brian Czech, for the concise and pithy rebuttal.

Ho ho! It is not necessary to rebut Brian’s criticisms, since conventional economists don’t seem to feel any need to ground their ideas in reality. The fact that they are also unable to predict anything of importance doesn’t seem to bother them either, nor the fact that their methods don’t support good public policy decision making. The fundamental problem (in my view) is that economics as currently understood and practiced is based on assumptions that are demonstrably false and that it uses bad logic to build on this shaky foundation. Even ecological economists tend to start with something about allocation of scarce resources but if you unquestioningly accept that bogus idea, you’re pretty much stuck with the rest. I think we need an entirely new economics that is true, understandable, and supportive of good policy decisions. This should start with “What is the economy?” and “What is the purpose of the economy?”. The economy is, of course, a system of practices, relationships, traditions, tools, and knowledge, and its purpose is to provide what people need and, if possible, what they want..Everything the economy produces is derived from five elements: energy, natural resources, time, knowledge, and ingenuity. The fundamental assumptions of a true economics should be that there is enough to go around (because there is) and that every person is born with an inalienable right to a share of everything necessary for a secure and productive life (because they are). It would be easy to prove that an activity that reduces any person’s access to their rightful share of life-sustaining resources and opportunities is a bad idea economically (because it actually is).

If you read Nordhaus’s books on climate change you will find, as I remember, that he does a nice rational economic man analysis, based on little or no knowledge of climate science, to conclude that the costs of climate change will be low enough so not much will need to be done until after 2050. And we wouldn’t want to do too much too early. This may be unfair criticism, it’s been a while since I read two of his books on climate. And he wasn’t enthusiastic about limits to growth either a couple of decades back, as I recall. His lousy a forecasts shouldn’t win a Nobel, in my opinion, but at least he was talking about climate issues, even if he got it wrong. But, oddly, even though the guy was wrong, there is at least a little bit of good from the Nobel prize because at least he was talking about climate as something real. So the message of the Nobel is, strangely enough “pay attention, this is real.” It makes pure denial harder. And, now that the weather has turned weirder earlier than scientists predicted and far earlier than Nordhaus predicted, maybe he can cover his tracks (past mistakes) by redoing his numbers yet again to bring them closer to reality. The IPCC process was supposed to build so much scientific consensus that it couldn’t be ignored, but in the age of propaganda and denial, that hasn’t worked very well, at least in the U.S.A. So the Nordhaus Nobel, coming the same year as bad hurricanes and fires might work as propaganda–which turns out to be more important than science. The scariest thing is that not only was Nordhaus wildly optimistic as it turns out, probably the IPCC process will turn out to be behind the curve as well. Jim Hansen, whose forecasts have been pretty good, worries about runaway, unstoppable warming to levels that will make human life really tough.

I found this article via Rob Mielcarski’s blog Un-denial; he does a first rate job scouring up the jewels critiquing conventional wisdom, esp economics related. I post to say, does no one care to examine in depth and critique the ‘Garrett Relation’ posited by atmospheric physicist Timothy Garrett at U Utah? Thermodyamically based, it says, inter alia, we cannot reduce energy expenditure because it is fundamentally linked to present-valued total global wealth (as defined). Just like I can’t stop ingesting food energy and expect to stay the same weight.

Here are links to his work:https://www.cabrillo.edu/~rnolthenius/Apowers/A7-K43-Garrett.pdf

https://www.earth-syst-dynam.net/3/1/2012/esd-3-1-2012-discussion.html

https://www.earth-syst-dynam.net/6/673/2015/esd-6-673-2015-discussion.html

FAQ in response to various confusions out there:

http://www.inscc.utah.edu/~tgarrett/Economics/FAQ.html

Garrett’s blog called nephologue. http://nephologue.blogspot.com

It seems Thomas Schelling repeated the same idea about agriculture and climate change for the US https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/1997-11-01/cost-combating-global-warming?cid=nlc-emc-Promo%20REmail%20-%20080317%20-%20Climate%20Wars%20eBook%20-%20Panel%20A-20170810&utm_source=Sailthru&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Promo%20REmail%20-%20080317%20-%20Climate%20Wars%20eBook%20-%20Panel%20A&utm_content=Final&utm_term=July%202017%20Promo%20-%20Group%20A%20REmail

Brian, a well-written and (if it weren’t so depressingly true) funny. You’ve really covered it all. But I’d like to add how neo-classical economist’s whole schtick is to only recognize labor and capital as the levers of an economy. Land as the third part of economic equations was banished from the mix when 19th-century industrialists wrote Henry George and his tax-only-land theme out of the history books by funding neo-classical economics departments and politicians. And here we are, over a century later, still suffering from the change.

Economics is the only science that believes in the perpetual motion machine. No wonder is was not included in the original Nobel real science prizes in 1901