The Oceans are Sending an SOS

by Gary Gardner

Media coverage of the loss of the Titan submersible last week turned the world’s attention to the oceans—that vast, mysterious realm that sits below the surface of our landlocked consciousness. Two factoids in the coverage caught my attention.

The first, emerging from chatter about the extent of the search effort, is that international law requires vessels to respond to an at-sea distress call if they are able to, an obligation dating back more than a century to around the sinking of the Titanic. The second, also related to the Titanic, is that it was the first ship ever to send out an SOS, a new distress code at the time. These tidbits from the margins of media coverage point to a legal, ethical, and technological regime in place for more than a century that makes the seas safer for seafarers and voyagers.

Oceans: A prodigious source of economic services (NOAA via Flickr)

Which sparks a thought: Imagine that regime extending from protection of ships on the ocean surface to the rich marine domain below. What if lawmakers had decided to protect the seas themselves, to maintain fish populations and prohibit the pollution that throws ocean ecology out of whack? The seven seas would surely be in better shape than they are today. In the absence of broad protections, the situation of the world’s oceans is serious: Many marine fisheries are collapsing, carbon pollution acidifies seawater, farm runoff creates marine “dead zones,” and a combination of practices is killing coral reefs. If these afflictions were the dots and dashes of Morse code, they would surely spell out “SOS.”

Protective rules for the oceans would also protect the world’s people and their wellbeing, given the many contributions oceans make to economies worldwide, even for landlocked nations. Consider that oceans:

- provide food to about a billion people who rely on fish, most of it marine-based, as their main source of animal proteins

- support economic activity, to the tune of trillions of dollars, through tourism, shipping, oil production, and fishing

- regulate the world’s climate, by circulating water and moderating temperatures, and

- protect biodiversity, including coral reefs, which are among the most species-rich ecosystems on the planet.

A proper response to the oceans’ SOS requires addressing the common driver of its diverse problems: the ongoing commitment, by governments, industry, and society at large, to ongoing growth. The pressures on the world’s oceans come from a growing global population, high levels of consumption in wealthy countries, and the need for more equitable economic opportunity in the poorest countries. Adherents to neoclassical economic theory believe that oceans and indeed all resources can be conserved and/or substituted for without curbing growth. But the case of oceans demonstrates both the allure and ultimate weakness of their case.

Ocean Demand is Surging

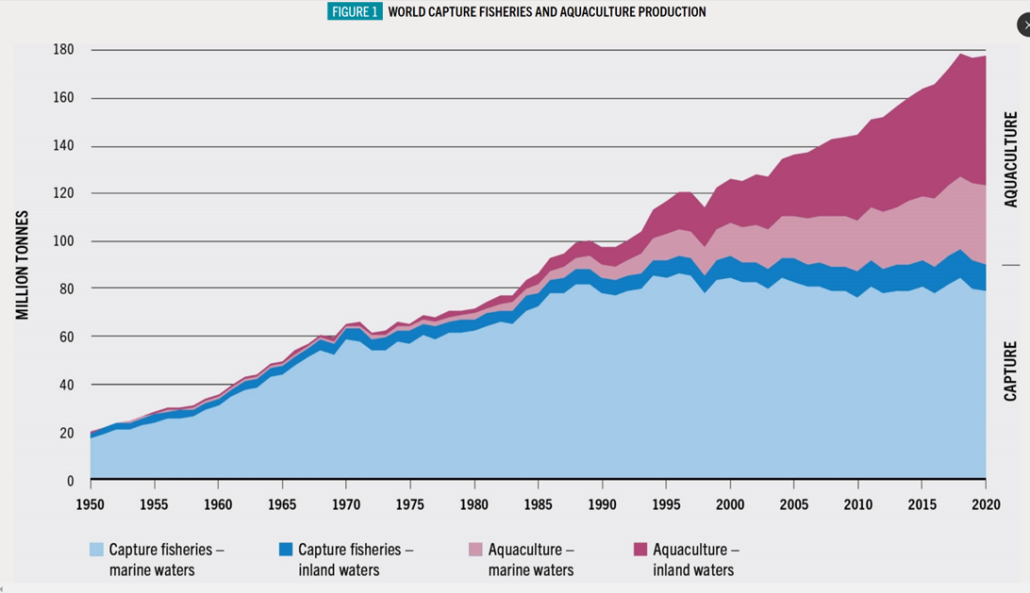

Pressure on oceans starts with the demand for marine goods and services that comes with a growing population and its expanding appetite for fish and other ocean products. Global population increased from 2.6 billion to 8 billion between 1950 and 2023, a large share of this coming in nations with high levels of fish consumption. Meanwhile, fish consumption per person also increased, from fewer than three kilos per year in the 1950s to nearly 20 kilos in 2015. The result: Between 1950 and 2020, global fish harvest increased twelve-fold, from 15 million tons to nearly 180 million tons.

However, the figure also reveals that fish catch (capture) has been essentially stagnant since the mid-1990s as fishers were unable to coax more from the oceans. The gap between surging consumption and stagnant production was filled using aquaculture, or fish farming. In fact, while aquaculture was a niche industry prior to the 1980s, providing only a marginal supplement to global fish catch, aquaculture now supplies more fish than wild catch does. This is a textbook case of substitution—a solution, neoclassical economists have long argued, to resource scarcity and a reason why economic growth is not a problem. Disappearing resources can be substituted for, as the swapping in of aquaculture seems to confirm.

Fish capture falters, aquaculture steps up (FAO)

But analysis of the substitution argument must consider the costs of aquaculture, not just its achievements. Farmed fish must be fed, and that feed has its own resource requirements. For most fish species, 1.5 to two kilos of feed are needed for each kilo of weight added to a farmed fish. That feed comes from other fish that are made into fishmeal, or from plant-based material grown on land. Moreover, raising fish in close quarters can spread disease and breed parasites, another set of concerns with resource costs.

In sum, aquaculture replaces what had been a self-provisioned good, wild fish, with a product that must be fed, raised, and cared for. All of this entails resource costs that must be factored into the resource balance sheet for aquaculture.

Ever More Clever Tools

Another argument neoclassical economists offer for continued growth is their faith that increasing efficiency will reduce the pressure of growing demand for resources. Once again, fish catch provides a useful case for questioning this argument.

Since 1950, fishing has become an industrialized endeavor with technologies that have enabled intensive fishing practices—including drift nets, longlines, GPS, sonar, and onboard refrigeration. The most sophisticated fishing vessels are now capable of staying months at sea and capturing dozens of tons of fish, which can be processed, packaged, and frozen on board, then quickly sold once in port. From the perspective of a ship’s productivity, this is a highly efficient operation. Again, the neoclassical argument scores points in its opening round.

But by other measures fishing today is less efficient than before the advent of super trawlers. In this era of increasingly depleted fisheries, today’s global fleet catches only 20 percent as much fish per unit of effort as it did in the 1950s (measured, for example, by catch per days at sea). More effort to catch the same tonnage of fish strongly suggests a depleted stock and should be a troubling metric for any observer, including neoclassical economists, no matter how efficient operations at the ship level appear to be. Another indicator of fishing inefficiency is bycatch, fish that are unintentionally caught up in the fishing process. Some 10 million tons of bycatch are swept up each year.

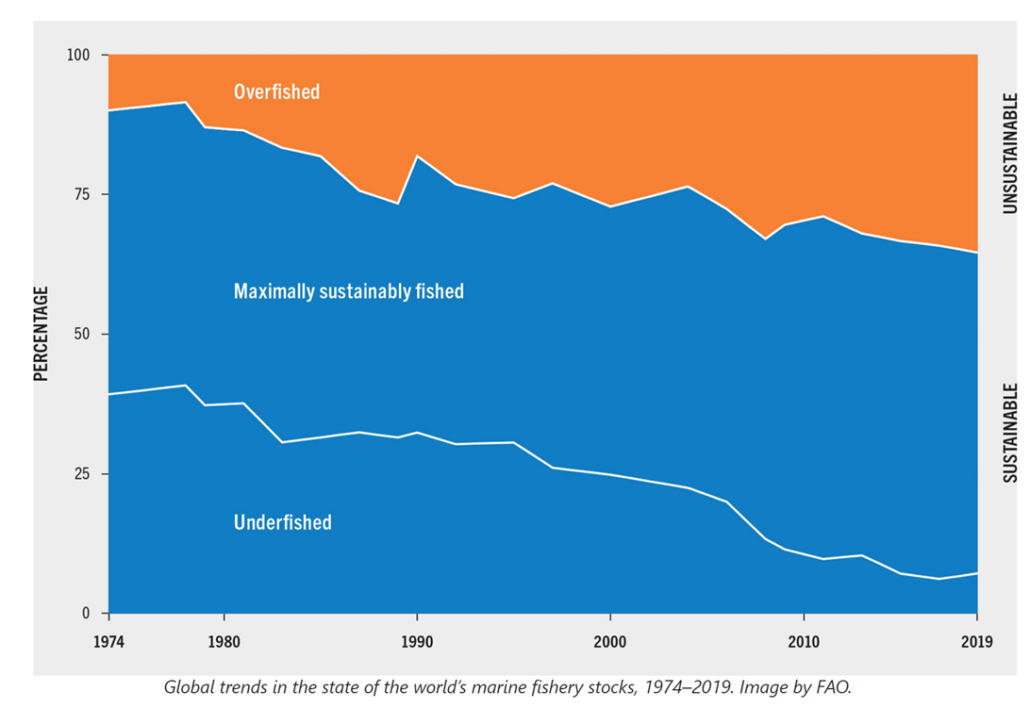

The result has been progressive depletion of fisheries: The Food and Agriculture Organization reported in 2022 that fishery resources continue to decline because of overfishing and other factors. Less than two-thirds (64.6 percent) of fishery stocks were at biologically sustainable levels in 2019, a reduction of 1.2 percentage points from 2017. This, in spite of a 10 percent reduction in fishing vessels since 2015 as China and the EU in particular work to reduce fleet sizes.

The result has been progressive depletion of fisheries: The Food and Agriculture Organization reported in 2022 that fishery resources continue to decline because of overfishing and other factors. Less than two-thirds (64.6 percent) of fishery stocks were at biologically sustainable levels in 2019, a reduction of 1.2 percentage points from 2017. This, in spite of a 10 percent reduction in fishing vessels since 2015 as China and the EU in particular work to reduce fleet sizes.

Pollution: Not Just a Local Problem

A growth economy comes complete with side effects, like pollution, that often escape market dynamics. Pollution is a big omission: it creates “dead zones” along coasts worldwide, die-offs of coral reefs, and acidification of ocean waters.

“Dead Zones”—As fertilizer runoff from farms flows into streams and rivers, then reaches the open sea, it creates nutrient-rich waters that fuel the growth of algae. The algae eventually die and sink to the sea bottom, where they are consumed by bacteria, a process that depletes the water of oxygen. Lack of oxygen drives away or kills fish and other marine life, resulting in a “dead zone” that can be quite sizable: the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico, formed by runoff from midwestern U.S. farms that enters the Mississippi River and flows to the Gulf, was nearly 8,500 square kilometers in 2022, about the size of Delaware and Rhode Island combined.

With the intensification of agriculture since the 1960s and the consequent use of greater quantities of fertilizer, the number and extent of dead zones worldwide has spread dramatically. The United Nations Development Programme identifies more than 500 dead zones worldwide, affecting a total area of some 250,000 square kilometers, about the size of the United Kingdom.

Degradation of coral reefs—Another major sign of the declining health of oceans is the state of coral reefs, among the most species-rich ecosystems on the planet. The Status of the Coral Reefs of the World 2020 reported that between 2009 and 2018, the world lost 14 percent of its coral reef area. Acidification of oceans is a key source of coral decline, but warming seas, pollution, and destructive fishing practices also take a toll.

The value of reefs to the environment and to humans is enormous—some $2.7 trillion. Although coral reefs cover only 0.2 percent of the ocean floor, they support some 25 percent of all marine fish species, making them a trove of biological wealth. Reefs act as centers of spawning, refuge, and feeding for a wide range of species. And because reefs are rich in species, they are typically important fishing areas, especially in poor countries. In addition, reefs protect coastlines from storm surges and violent wave action, and are a growing source of ingredients for new medicines.

Acidification—The world’s oceans are about 25 percent more acidic than before the Industrial Revolution, largely the product of steadily rising levels of pollution carbon dioxide, which is absorbed directly from the atmosphere. In fact, and about a quarter of humanity’s annual atmospheric emissions of carbon end up in the ocean. CO2 reacts with seawater to raise the acidity of the water; today’s acidification rate is estimated to be 10 to 100 times faster than at any time in the past 50 million years.

Acidification causes the shells and skeletons of “marine calcifiers”—corals, oysters, clams, mussels, and snails, in addition to phytoplankton and zooplankton that form the base of the marine food web—to dissolve more readily. By the middle of the century oceanic accumulation of carbon dioxide is likely to be twice as great as prior to the industrial era, creating increased acidification pressures. Indeed, at continued high rates of carbon emissions, acidity could increase by 170 percent by 2100.

Dissolving pteropod in seawater with the pH levels projected for 2100. (NOAA)

Oceanic history provides clear warning signs of the harm from acidification. An increase in atmospheric carbon and oceanic acidification 55 million years ago—at rates far slower than today’s—produced a mass extinction of marine species, especially deep-sea shelled invertebrates. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change observes that acidification of oceans over the rest of the century could produce ocean changes similar to those observed during the event 55 million years ago.

For all the trouble that ocean acidification portends, ocean absorption of carbon is also credited with slowing the rate at which the planet is warming, because the carbon taken up by oceans would otherwise have remained in the atmosphere. But this blessing is likely to diminish: As the world’s oceans warm and as oceans become saturated with carbon, the rate of oceanic accumulation of carbon is projected to fall.

More than an SOS

In sum, the world’s oceans are sending out an SOS, but the message goes unheeded. The historical record once again serves up food for thought. The crew of the Titanic sent out multiple distress signals that tragic night in April, 1912, including the traditional “CQD” signal, the predecessor to the SOS. In the wireless telegraph world of 1912, “CQ” indicated broad distribution—that all stations should sit up and listen—while “D” signaled “distress.”

An “all stations” message suggests a worldwide response is needed to answer the oceans’ distress call. “All stations” also suggests a need to look at the problem broadly—not as a set of technical marine fixes but as a comprehensive challenge of system design—then correcting the root issue: the ongoing growth in population and economies. Whether the challenge is framed as an SOS or a CQD, our response needs to be quick, comprehensive, and robust if we are to avoid a Titanic-level catastrophe for the Earth’s oceans.

Gary Gardner is Managing Editor at CASSE.

Great line for a chilling story: “If these afflictions were the dots and dashes of Morse code, they would surely spell out SOS.” The Bureau of Labor Statistics lists fishing worker as the seventh most dangerous job, based on fatal work injuries. Perhaps there’s a way to combine protection of the oceans with protection of those who work at sea.

Yikes, this is sobering. All I can add is that for me, this reinforces the insight that holding the banner for a steady state economy is by far the best use of my limited time and resources as a private citizen. There are many worthy ideas and causes out there, but I don’t think anything else compares.