Water Theft in the Heartland: The Case of Tippecanoe County

by Dave Rollo

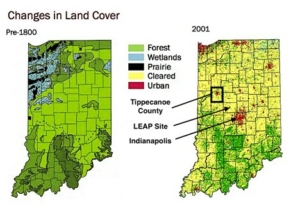

Indiana’s wetlands and rivers were appropriated for ag use, leaving cities dependent on groundwater. Green shading in left figure indicates different forest types. (Indiana University Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences).

Imagine a landscape with some of the richest wildlife habitats in North America. Settlements are scarce and water is plentiful. Birds dot the skies, mammals abound on the ground, and fishes fill the rivers and lakes.

That’s Tippecanoe County, Indiana. In 1800.

The county’s transformation over the past two centuries would make it unrecognizable to its original inhabitants. Today, much of Tippecanoe consists of flat plains of fertile soils. They host vast expanses of farmland, spotted with a few hills and valleys. The county’s makeover is emblematic of the change in much of northern Indiana.

The region’s extensive conversion to farmland brought changes that reverberate across the landscape today. A great example is the draining of the great midwestern marsh of northern Indiana—the Kankakee Grand Marsh, once comparable to the Everglades in size and biodiversity. Its elimination in the late 19th century caused half a million acres of wetlands to vanish, including the largest natural lake in Indiana. The loss rendered the landscape nearly devoid of surface water. It forced settlements to turn to the remaining rivers or groundwater to meet urban needs and to irrigate farmland. This conversion of wetlands to farmland contributed to water scarcity in Indiana and set the stage for battles over water resources today.

Growing Demand

Tippecanoe County, like most of west-central Indiana, is increasingly reliant on groundwater. The Teays Aquifer, which extends beneath ten counties in the region, is now the essential water source for Tippecanoe, together with the Wabash River, which is overused.

The Wabash River in Northern Indiana. (Chris Light, Wikimedia).

One of those ten counties is Marion County where Indianapolis dominates municipal governance. Given its projected water needs, the county may find the available water supply to be too confining. Dependent on the White River and the county’s own aquifer, city leaders and developers have long coveted surrounding water resources for the city’s expansion. In 2006 the city attempted to tap Monroe Lake, a reservoir some 60 miles to the south. That project failed after considerable resistance from multiple jurisdictions and state officials, including the governor.

The target of the growth boosters of Greater Indianapolis is the Teays Aquifer. They propose to transport water 50 miles to advance the largest development project in the state’s history. Developers call it LEAP, the Limitless Exploration/Advanced Pace Research and Innovation District. LEAP is a megasite—a type of enormous industrial and manufacturing center developed as a group effort by state agencies, universities, and private developers.

Unlike a failed attempt in 2006, LEAP has the support of the current governor. But whether appropriation of the water for distant growth ambitions comes to pass remains to be seen. The battle is just beginning.

The Wabash Consumed

We often think of water wars as occurring in the western USA. But conditions are shaping up for similar skirmishes in the Midwest. As recently as the fall of 2023, drought impacted some 50 percent of the Midwest. And periodic severe droughts have tested regional water providers. Furthermore, climate modelers predict that Indiana will have wetter springs but drier falls, with higher temperatures creating stress on humans and crops alike.

Already, seasonal droughts in Tippecanoe County have impacted the largest surface water source in the region, the Wabash River. Its watershed encompasses two-thirds of Indiana, and cities in the catchment area draw heavily from the river. During the summer, cities withdraw river water at nearly the same rate they replenish it. (Replenished supply is water used by power and sewage plants that is treated and returned to the river.) In other words, during its period of lowest flow, municipal users appropriate nearly the entire supply of river water. What will happen as demand for water grows?

The county also gets water from the Teays Aquifer. The twin cities of Lafayette and West Lafayette depend entirely on the aquifer to meet residents’ needs.

The Wabash River watershed serves much of Indiana and a significant portion of Illinois. (Wikimedia)

Tippecanoe County may have a secure water supply for the time being. But counties to the east and close to Indianapolis are not as fortunate. Boone County has rich agricultural farmland, but little subsurface water due to its underlying geology. So it has little potential to increase extraction. Yet the economic development community in Indianapolis has targeted Boone County—25 miles northwest of the city—for the enormous LEAP megasite.

LEAP is an industrial park facility with centers for pharmaceutical development, silicon chip manufacturing, and data storage. It is under construction on 10,000 acres of some of the best farmland in the state. It’s situated along Interstate 65, a superhighway connecting Indianapolis and Chicago.

Analysts estimate LEAP water needs at up to 100 million gallons per day. Yet Marion County (Indianapolis) and the counties surrounding it have no spare water capacity. For this reason, project developers propose to run a pipeline more than 50 miles to extract water from the Teays Aquifer in Tippecanoe County. This $2 billion pipeline plan has alarmed the public and brought scrutiny to LEAP. Yet many aspects of the project remain obscure.

Growth Boosters Shift Costs to the Public

The Indiana Economic Development Corporation (IEDC), whose board is appointed by the governor is a major cheerleader of LEAP. The IEDC and its associated foundation is a public/private partnership that is opaque to public scrutiny. Yet is Indiana taxpayer fund it to the tune of billions of dollars.

The IEDC keeps secret the names of private donors who provide supplementary funding, as donors request anonymity. But the public lobbying group Common Cause has noted that a thank-you to sponsors on the IEDC website mentions the five largest investor-owned utility companies in the state. IEDC has also been evasive regarding LEAP. It refuses to share internal reports, excluding the public from meetings, and failing to answer questions posed by citizens, citizen advocacy groups, and the media.

A December 2023 report from the largest citizen/consumer advocacy group in the state, the Citizen Action Coalition (CAC), found “significant and valid concerns” regarding LEAP. It also found that the project “will likely lead to an environmental and financial crisis for Hoosier taxpayers and utility customers.” The report notes that LEAP’s projected water extractions from Tippecanoe County may exceed the water use of 1.3 million average Indiana residents.

A sliver of the LEAP vision. (IEDC)

Tippecanoe County, with a population of 186,000, currently uses 35 million gallons/day from the aquifer—about a third of LEAP’s potential impact. Furthermore, the $2 billion cost of the pipeline and expansion of related utilities is as yet uncertain. (How often do we find massive infrastructure projects come in under cost?) The CAC warns that the cost of adding such capacity may well be borne by customers.

The CAC further revealed that the IEDC purchased the 10,000 acres and committed to greenlighting the site prior to securing the water needed or even conducting a water study of the project. It purchased some farmland at up to six times the assessed value. One farmer reported being approached by IEDC attorneys who “refused to disclose who they worked for or the reason behind the land purchase.”

After issuing their report, the CAC (along with major media outlets and local government officials) has requested answers to numerous questions raised by the LEAP project. Yet the IEDC has refused to meet or even respond. This led WTHR in Indianapolis to report last December that “Over the past eight months, the IEDC has refused all of our interview requests to discuss the project.” The IEDC even ignores inquiries posed by Tippecanoe County elected officials, whose municipal water may be affected by the pipeline. “The project has been shrouded in secrecy and lack of responsiveness since its initiation. Only public pressure has resulted in any willingness to discuss, in a very limited fashion and mostly through press releases, the potential for large-scale water diversion,” David Sanders, a West Lafayette city council member, told me in an interview.

Pushback from Tippecanoe County

Citizens and public officials are pushing back on the LEAP pipeline in Tippecanoe County. Both Lafayette and West Lafayette have passed resolutions against tapping their aquifer. Tippecanoe County has passed a moratorium on high volume withdrawals for the next nine months.

Stop the Water Steal, a citizen group founded by Councilmember Sanders, has rallied residents in Tippecanoe County to resist the pipeline and work toward an independent water analysis that will evaluate the effect of a potential 100 million-gallon-per-day extraction from the Teays Aquifer. This evaluation has been supported by legislators at the Indiana Statehouse.

Tippecanoe citizens are pushing back against the pipeline that threatens their water supply. (Stop The Water Steal).

Richard Meilan, Professor of Natural Resources at Purdue University in W. Lafayette, found that test wells for the project created a drawdown of 1.5 feet after only a 2-million-gallon withdrawal over a 72-hour period. He lives only a mile from the test wells and spoke directly to a drilling company employee who expressed surprise at the decline of the water table. Dr. Meilan, CAC, and Stop the Water Steal have all remonstrated in public forums. Their efforts have garnered seventeen resolutions against the pipeline from county and city jurisdictions as far away as Bloomington, some 100 miles distant. “Don’t take the LEAP” might summarize their message.

Such resistance has prompted Indiana Governor Holcomb to pause the LEAP proposal pending further analysis of the pipeline’s impact by the Indiana Finance Authority (IFA). However, CAC Director Kerwin Olsen says this should not be considered a fully independent study. The IFA is under the authority of the governor, who is also Director of the IEDC Board. The delay, according to Olsen, is a political response to lower the project’s profile during an election season.

Fortunately, the delay also provides additional time for citizens and their representatives to continue to spread the word, gather evidence, and build resistance to the water theft in the heartland.

Dave Rollo is a Policy Specialist and team leader of the Keep Our Counties Great campaign at CASSE.

CC BY-NC 2.0, Creator: Stuart Rankin

CC BY-NC 2.0, Creator: Stuart Rankin

Thanks for this great story!

Who knew that little, old Indiana would catch the eyes of CASSE and yourself.

The LEAP development is an environment travesty of the first order. However, in this state, as in many communities across the US and world the pursuit of money and profit outweighs any and all considerations for the environment and our quality of life. (Jobs! Jobs! Jobs! Go the brain-dead politicians.) There are many other smaller, contemporary stories of Indiana’s determination to be first…at the bottom.

Although I consider the prospects of really stopping this project nil maybe, as you say, the delay for faux reconsideration is time to build one last great act of defiance.

For me as a Californian, this story sounds all too familiar. Good luck people of Indiana in stopping this thing, if not now, hopefully eventually.

from concerned citizen