American Totalism: Technology, Economy, and Nationality

by Brian Snyder

Nicholas II and his family unaware that their totalitarian state would rise against them. (CC0, Source)

“Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality.” Those were the principles that underlaid most of the Tsarist governments in the final 80 years of Romanov rule. It was a slogan and a belief system, Russia’s version of “liberté, égalité, fraternité.” Eventually, under the leadership of a poor autocrat, Nicholas II, it would lead to the Russian Revolution and the brutal murder of Nicholas and his family. Yet between its coining in 1832 and the Revolution in 1917, “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality” established a framework for a nascent totalitarianism.

The nascent totalitarianism matured under Lenin and was “perfected” under Stalin, but the Soviets used a different tripartite slogan: “Peace, Land, and Bread.” Despite its less reactionary tone, the Bolshevik’s slogan was even more effective in creating a totalitarian state, perhaps because of its more positive spin. After all, who could oppose peace, land, and bread?

State totalitarianism never emerged in the West. Yet totalism is alive and well in the USA, and it is underlaid by its own tripartite foundation: “Technology, Economy, and Nationality.” These three concepts may not be an explicit slogan (yet) in the way “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality” was, but they are the aims of American totalism.

Totalism and Totalitarianism

First, we must differentiate between totalitarianism and totalism. Totalitarianism is the control of individuals by the state. As defined by psychologist Robert Lifton, totalism is the control of individuals by other individuals or groups. Thus, a cult is totalist but not totalitarian. Furthermore, unlike totalitarianism, totalism does not require leadership in a single person or governing class. Totalism can be an emergent characteristic of the group. In this case, totalism is not monitored by a Gestapo-like police state but by other members of the group.

The USA and other Western societies are not totalitarian, but they are totalist. Rather than autocratic leaders dictating and enforcing cultural norms, we enforce these norms ourselves. Yet without autocratic leaders, who benefits from this totalism? In the short term, we all do via an increase in the number and diversity of our material possessions. Yet, like nearly every totalitarian regime in history, our totalism is not sustainable and will collapse as the costs of our prosperity and possessions erode the ability of the totalism to function.

Technology

One of the most insightful thinkers on the role—or rather control—of technology on modern society is Wendell Berry. His recent compilation of essays, The World-Ending Fire, is full of critiques of technology in the modern world, but one is particularly interesting. In the late 1980s, Berry wrote an essay describing why he preferred to write with a pencil rather than use a computer. It was a short essay that described his work habits, some of his rules for replacing an existing technology with a new one, and whether new technology actually improves our lives.

We might think that one person’s decision to eschew the computer would not be controversial, but Berry’s publisher, Harpers, received dozens of letters from readers outraged that a person would criticize computer technology. They argued about how useful a computer was, called Berry a misogynist because his wife typed his writing on their typewriter, and labeled him a hypocrite for using other technologies. But why would anyone care?

They cared—were outraged in fact—because Berry had violated the expectations and norms of society. Berry spoke out against technology, one of the pillars of the totalism. While they did not send Berry to the Gulag for his transgression, they effectively policed his thought.

Yet the debate about Berry’s writing tools is the result of a well-established technological totalism. The age of the personal computer did not mark the dawn of technological totalism but rather an already-established totalism that was first noticed by the French sociologist and philosopher Jacques Ellul in his 1954 magnum opus, The Technological Society. According to Ellul, technology, or what Ellul called “technique,” was not subservient to humans. Instead, humans became subservient to technique. Indeed, Ellul’s distinction between technique and technology is instructive. Technique is the system that prizes efficiency above all else. It is technology, but it is also sociology underlying its use and the cultural movement toward efficiency. Thus, technology is a subset of technique. When Berry’s detractors criticized his rejection of the computer, they were criticizing his failure to uphold the technique.

According to Ellul, “Technique cannot be otherwise than totalitarian […] Totalitarianism extends to whatever touches it, even things which seem, at first sight, very remote from it. When technique has fastened upon a method, everything must be subordinated to it” (125). And, “No technique is possible when men are free […] Technique must reduce man to a technical animal, the king of the slaves of technique. Human caprice crumbles before this necessity; there can be no human autonomy in the face of technical autonomy” (138). Or, in the more straightforward language of Ellul scholar Darrell Fasching, “Modern technology has become a total phenomenon for civilization, the defining force of a new social order in which efficiency is no longer an option but a necessity imposed on all human activity.” [Emphasis added.][1]

In the intervening decades, I would argue that Ellul’s thesis and Berry’s pencil have been proven correct. Technology continues to advance, but (to borrow from Robert F. Kennedy’s famous 1968 speech at the University of Kansas) these advances have done nothing to improve our children’s education or the quality of their play. They have not improved our poetry or marriages, the intelligence of public debate, or the integrity of public officials. They improve neither our wit nor courage, neither our wisdom nor learning, neither our compassion nor devotion to our community. They improve everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.

Economy

The totalism of the economy is discussed by Herman Daly, although, to my knowledge, he does not use the term. Nonetheless it is an underlying theme of his, and of many other anti-growth economists. Here, the argument is that the “health” of the economy has become a cult, and we all worship at its altar. As if it was our own child, the health of the economy is measured by its growth, and when our economy’s growth slows or reverses, people become alarmed.

The economy and its wellbeing exert vast control over our public policy, from local decisions about zoning to global decisions about free trade agreements. At the local level, we sacrifice our children’s literal health for the economy’s metaphorical health when we offer tax incentives to polluting industries to expand in our cities and states. At the global level, we sacrifice our employment to technology or globalization because it increases efficiency and thus GDP growth. At the national level, we cut taxes on the wealthy and corporations to stimulate growth, and then borrow money from the same wealthy individuals and corporations to pay for our military-industrial complex.

Our personal lives are just as motivated by economic growth, yet we are unaware of its control. It is pernicious. Thirty years ago, if you were settled down to dinner with your family and your boss called your phone, you would assume that something terrible had happened, such as a fire at the office or the death of a co-worker. Yet ten years later, a generation of workers were given Blackberries in the name of “progress,” and they became tethered to their bosses and coworkers 24 hours a day. This progress was not for the workers, nor was it for the bosses, who became no less chained. It was for the economy. Today, I am listening for the ping of my email every moment I am awake. Undoubtedly, I am more productive for my employer than I could have been three decades ago. But why? At what benefit, and at what cost?

Equally concerning is the fact that no one planned any of this. It is not some conspiracy by a cabal of industrialists in a smoke-filled back room. The distribution of Blackberries was not the result of a secret government agency. It simply happened because we are embedded in a totalist society, all happily playing our part in the industrial economy and believing that some of the expanding mammon will trickle down to us.

As is the case with technology, we police those who blaspheme our economy. For a time, admitting you were a socialist was a greater sin than belonging to the Ku Klux Klan. Today, even those who criticize economic growth from a capitalist perspective are considered to be naïve, misinformed, and an impediment to progress. Totalism does not require that its critics be silenced, but it does require that they be thought of as kooks. Economic totalism, with its hundreds of thousands of neoclassical economists, is quite adept at that.

Nationality

While Jacques Ellul may be the great prophet of technological totalism, and Herman Daly plays the same role for economic totalism, we might consider Stanley Hauerwas to be seer of nationalist totalism in the USA, although he had plenty of forbearers. Hauerwas, a theologian and scholar of Christianity, argues that America has a civil religion which revolves around the flag and war. This civil religion has its sacred holidays (the Fourth of July, Veterans Day, Memorial Day, etc.), a sacred text (the U.S. Constitution), near mythical ancestors and saviors (for example, George Washington and Abraham Lincoln), and even divine miracles (July 4, 1826).

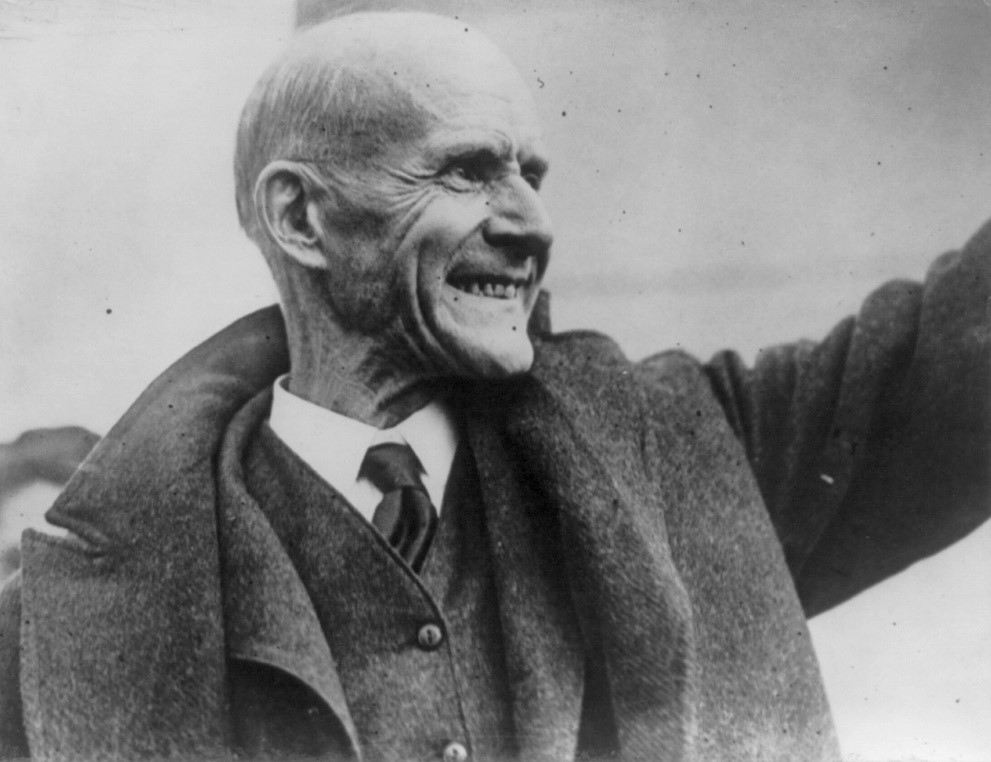

Eugene V. Debbs, Socialist U.S. Politician, leaving prison in 1921 after being jailed for nearly two years for criticizing the U.S. government during World War I. (CC0, Source)

In 1918 Eugene V. Debbs observed, “In every age it has been the tyrant, who has wrapped himself in the cloak of patriotism, or religion, or both.” Our civil religion is both, patriotism masquerading as religion, but it is not the tyrant who has deceived us; we have only ourselves to blame. The same civil religion that binds us together is also a way we enforce totalism. Criticism of the flag, the troops, or whatever war we happen to be in today is thought to be un-American and prohibited by the group.

Hauerwas would argue that this civil religion reinforces militarism and war, but that is not my immediate concern. Instead, the primary fruit of our civil religion is understood to be our freedom. We are told that we could not have our freedom without the sacrifices of generations of soldiers. I do not intend to dispute that, especially given the prohibition I just mentioned, but what is this freedom that is so critical to us?

Free speech? Freedom of the press? Of religion? I do not mean to imply that we do not value those freedoms, but I do think that the freedom we hold most dear is the free market. At least once in our history, we have abrogated every freedom in the constitution from at least one segment of our population (e.g., slavery, Jim Crow, the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, the Sedition Acts of 1918, Japanese internment, etc.), but we have never violated the free market. Because the free market is taken to be a result of American civil religion, it is sacrosanct. Because the “health” of the economy depends on the free market, the economy becomes sacred, and so our nationalism and economy are intertwined.

American Totalism

Ellul argued that as totalitarian regimes develop, their control becomes less obvious and more sophisticated.[2] For example, early totalitarianism in the Soviet Union was brutal and public (e.g., the Red Terror, the Great Purge, etc.). By the end of Stalin’s life, he had created a complex system of propaganda, fear and domestic espionage that controlled the population without resorting to genocidal purges. Indeed, Stalin’s totalitarianism was so effective that it went unnoticed by many of his citizens.

In the same way, we should not expect to easily discern the totalism of “Technology, Economy, and Nationality,” but nearly every part of our lives is controlled by the totalism. What we get our children for Christmas is controlled by marketing and keeping up with the Joneses (a phrase that tacitly accepts this totalism). The jobs we accept are decided by the paycheck, as are the extended hours we work. The houses we buy, as well as the cars, televisions, cellphones—none of these decisions are dictated by what we need or what will bring us actual joy, but by a need to fit in with the totalist group. We are both the oppressor and the oppressed.

Totalism is not totalitarianism, and being in the thrall of a growth economy is not equivalent to the Red Terror. Yet over the long term, totalitarian systems typically collapse or become less totalitarian to adapt to changing circumstances. I am not sure if the same will be true of American Totalism before it is too late.

Footnotes

[1] Brueggemann, W. 2018. Tenacious Solidarity: Biblical Provocations on Race, Religion, Climate, and the Economy. Fortress Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

[2] Fasching, D. 1981. The Thought of Jacques Ellul: A Systematic Exposition. Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston, New York.

Brian Snyder is an assistant professor of environmental science at Louisiana State University and CASSE’s LSU Chapter director.

Brian Snyder is an assistant professor of environmental science at Louisiana State University and CASSE’s LSU Chapter director.

These three links definitely reinforce your assertion about technology not advancing our species as planned…and they’re all extremely troubling. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uaaC57tcci0 & https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aisZHLj1vYk & this one should scare everyone: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oe3y-OdNSsw&feature=youtu.be&fbclid=IwAR0531sIpO4Nv_P_PUdyB4yuAz6D5Oz3YUkyBnTv9ekTxwgy5nqlWFUBd0E

And this PBS series also points out the just how technology hasn’t been the salvation that some thought it would be.

https://www.pbs.org/show/hacking-your-mind/

There are two other dimensions of “totalism” that are even more widely shared–the refusal to acknowledge our ever-increasing human population as a problem, making it “taboo” to speak about, and the anthropocentrism that is required to maintain a devastatingly exploitative market in animal parts (domestic and wild) that our economism demands.