Biden’s Black Swan: New Oil Leasing is Bound to End in Disaster

by Taylor Lange

The USA is well acquainted with disastrous crude oil accidents. Eleven years ago an explosion on the Deepwater Horizon oil platform killed 11 workers, injured 17 more, and discharged roughly 4.6 million barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico. The incident cost BP more than $65 billion to clean up, destroyed thousands of acres of ocean reefs, and killed thousands of marine animals. Just over two decades prior, the Exxon Valdez spilled 11 million gallons of oil into an ecologically sensitive area of Prince William Sound, Alaska, effectively killing a quarter of a million sea birds and several thousand sea mammals. Most recently, a crack in an underwater pipeline caused by a rogue anchor released close to 25,000 gallons of oil off the coast of Orange County, California.

Despite this, President Biden’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) has followed through with a Trump-administration leasing plan that will open up 80.9 million acres of deep-sea floor in the Gulf of Mexico to oil and gas drilling. Apparently, this is what leading on climate action by example looks like in the Biden Administration. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

In 2010 we published a Daly News article about the BP oil spill, explaining that a spill of that magnitude was literally, statistically bound to happen because of the scope of oil production at the time. As we consider the implications of the new leasing plan, it’s worth revisiting why unlikely events like massive oil spills occur in the first place. The answer lies in the laws of probability, which we disregard at our own peril.

Observing Black Swans

For millennia, Europeans regarded black-feathered swans with incredulity because Europe’s swans are exclusively white. Because of this, many Europeans used the term “black swan” to describe something impossibly rare. For example, in “The Ways of Women,” the Roman poet Juvenal mocks his friend for being too preoccupied with finding the perfect wife, describing her as “a prodigy as rare upon the earth as a black swan!” That all changed in 1697, when Dutch Explorer Willem de Vlamingh stumbled upon black swans while exploring present day Western Australia. From that point on, the “black swan” idiom evolved to refer to something assumed to be impossible but could be later discovered possible. The mathematical statistician and philosopher Nassim Nicholas Taleb then adopted the term to describe events with minute probability and substantial impact.

Deepwater Horizon is just one example of many catastrophic oil spills, with many more to come. (CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0, Kris Krug)

Taleb argued that many influential events in human history had such a low likelihood of occurring that they were nearly unpredictable. But black swan events are only unpredictable from a certain point of view. One such black swan event is the September 11th terrorist attacks on U.S. soil. From the perspective of the average U.S. citizen, the attack was completely unexpected; nobody knew of plot against the USA by Al-Qaeda, and most citizens comfortably assumed that our national security apparatus and law enforcement agencies would detect and squash any potential threat. Despite American surprise, however, the attack was inevitable from the lens of the perpetrators.

The Deepwater Horizon event could also be categorized as a black swan event. Though minor oil spills are relatively common, a disastrous explosion resulting in over 4 million barrels of spilled oil was almost inconceivable to most people. But for experts in the industry, it was not only conceivable, but foreseeable. After all, BP experienced an eerily similar well failure 18 months prior in the oil fields of Azerbaijan due to similarly shoddy cement work. Not only that, Deepwater Horizon was overdue for 16 inspections at the time of the spill, with the most recent inspection completed by someone still in training. Even further, the U.S. Department of the Interior was rife with corruption, and inspections across the region were far below standard. In other words, some insiders were aware a Deepwater event was sure to happen soon, while the rest of us were left completely unprepared.

Odds of an Oil Spill

To put Deepwater Horizon into perspective, consider the empirical probability of an oil spill. In 2012, BOEM conducted an historical analysis of spill rates for platforms, pipelines, and tankers, measuring the spill rate as the number of spills per billion gallons of oil transported. Using this method, we combined data on oil spills from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and oil production from the Energy Information Administration to extrapolate the probability of oil spills in the future contingent on the amount of oil produced.

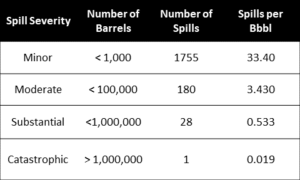

Figure 1. Spills were categorized into different severities according to the number of barrels released and counted from 2001-2020 (Bbbl = Billion barrels of oil produced)

From 2001 to 2020, the USA produced approximately 52.54 billion barrels of crude oil across all production facilities, including offshore platforms and land wells. During the same period, 1,964 spills of crude oil or an oil derived product (like gasoline or diesel) occurred, including Deepwater Horizon. Though most of these spills were minor, there was at least one substantial oil spill of more than 100,000 barrels (but less than a million) each year, and a little less than nine times that number of moderate spills (Figure 1).

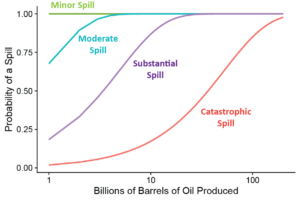

Assuming these rates continue, we can calculate the probability of each severity of spill occurring over the next 20 years[i] (Figure 2). To nobody’s surprise, minor and moderate spills are all but guaranteed, even at very low amounts of production. Furthermore, the probability of substantial and even catastrophic spills is very high, given the levels of production called for by Trump-like or Bidenesque GDP goals.

Figure 2. Probability of at least one spill of each severity occurring by the potential number of barrels produced in the USA, logarithmically scaled.

Biggie was Right: More Money, More Problems

The more we produce, the more opportunities we create for things to go wrong, resulting in a higher likelihood that they will. As oil production increases, more individuals must be employed to handle the oil, more pipelines constructed to transport it, and more tanker trips to ship it. At every point along the supply chain, growth creates more opportunities for malfunction and calamity.

It is worth mentioning that Taleb advises against trying to predict black swans, as the amount of information required to predict them is almost impossible to collect. Instead, he advocates for the creation of what he calls “antifragile systems,” which develop with the acknowledgement that black swans will happen and have appropriate coordinated responses in place. These systems have compensation mechanisms based on past mistakes that allow them to accommodate and grow from future shocks.

Biden’s decision to follow through with his predecessor’s plan to lease half of the Gulf of Mexico is perhaps the most fragile decision the leader of our country could make. It perpetuates the use of fossil fuels and contributes to additional greenhouse-gas loading of the atmosphere. Ironically but unsurprisingly, then, the decision exacerbates climate change and increases the likelihood of catastrophic weather events that further increase the risk of oil spills.

The increasing certainty of these accidents was a more than acceptable cost of pursuing GDP growth for the previous administration. Disappointingly, it appears that the sentiment is shared by Biden. As such, our commitment to the behemoth of economic growth will continue to expose us to an ever-looming and ever-growing probability of disaster.

Footnotes

[i] For those interested in our calculations, the code and data used in this blog are available on CASSE’s GitHub account.

Taylor Lange is the ecological economist at CASSE.

Taylor Lange is the ecological economist at CASSE.

"Rappahannock County Courthouse" by taberandrew is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

"Rappahannock County Courthouse" by taberandrew is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

"Rappahannock County Courthouse" by taberandrew is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

"Rappahannock County Courthouse" by taberandrew is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Thank you for this article. Another black swan is LNG transport by rail, truck, ship.

Very interesting (and sobering). Kudos for the logarithmic modeling, the resulting frequencies of events speak for themselves!