Bottom-Up or Top-Down: How to Degrow the Economy

by Vlad Bunea

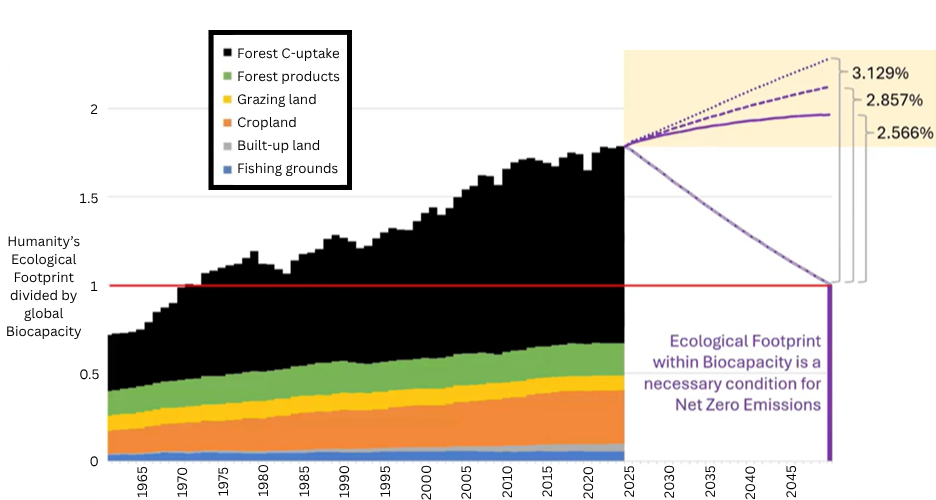

The Big Picture: the world’s 2025 ecological footprint and biocapacity accounts. (York University, Footprint Partnership)

To stop global warming, the 6th mass extinction, and ecological unravelling in general, humanity must degrow its ecological footprint very fast. We must degrow by 2–3 percent per year until our footprint falls under the planet’s biocapacity to regenerate itself. The only way to do this is to completely overhaul our growth-oriented, capitalist economic system.

There is a passionate ongoing debate in degrowthUK’s Prospects for Degrowth series about how to achieve this. The debate could be categorized into two approaches: bottom-up and top-down.

Those who favor the bottom-up approach advocate for the evolution of thinking and behaviors at a personal level. They call for a voluntary rejection of capitalism and the adoption of a simple, anti-consumerist lifestyle. These “bottom-up-ers” include: adopters of voluntary simplicity, ecovillage inhabitants, those living off the grid, minimalists, the Amish, self-conscious urbanites, communitarians with ecological awareness, and the financially independent “sustainability class.” One extreme, fictional portrayal of the bottom-up approach is the Captain Fantastic family, living in the forest and educating themselves in Chomsky and Marx.

Those who favor the top-down approach advocate for massive reforms at the level of the state, for a post-capitalist societal transformation. “Top-down-ers” hope that the right kind of laws and regulations, like the Steady State Economy Act, will change lifestyles and cultures. Top-down-ers include: members of environmental activist organizations, union members, political activists, and both academic and non-academic policy wonks.

Differing Perspectives on the Need for Change

Bottom-up-ers tend to say that it is futile to convince the government to adopt degrowth, because governments are captured by the flaws of electoral democracy. They must operate under popular mandates, and they are lobbied by special interest groups, so they defend the capitalist status quo.

Is top-down change possible, or is the government too corporate-captured? (BUNDjugend, Flickr)

Top-down-ers tend to say that it is futile to convince people to adopt simplicity, because people never actually change without pressure from some external force. They say it takes laws and regulations, social stigma, war, pandemics, etc., to spur real change. Some top-down-ers go as far as proposing climate Leninism, an aggressive strategy to solve the climate crisis fast, predicated upon the rise of a “revolutionary party.”

Most people aren’t aware of the multitude of approaches to economic reform, let alone the debate over bottom-up versus top-down degrowth. However, a growing majority of people recognize the need for systemic change. The following perspectives are common:

- I hate our capitalist system. I can barely make rent, and I live paycheck to paycheck. But I still want to fight. What do I do?

- I hate our capitalist system. I make okay money. I have some savings. I own my home. I have some free time, and I want to fight. I live in a big city. I cannot leave it, because my family is here. What do I do?

- I am agnostic about capitalism, but I do think the system is fundamentally broken. I think oligarchs have too much power. We need a completely new economic system, but I do not want to lose any of my hard-earned assets. I don’t have time for activism, but once in a while I donate money to a cause. Am I doing okay?

Why the Emphasis on Capitalism and not Simply Economic Growth?

Zooming out briefly, let’s consider the primary source of the reckless economic growth that has sent humanity beyond planetary boundaries: capitalism.

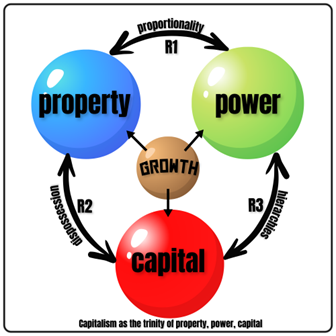

Avoiding the capitalism elephant in the room does not advance the conversation. We must say it like it is, even if it sounds jarring to many ears. We must also acknowledge that different people have different definitions for capitalism. A useful definition of capitalism encompasses its foundational doctrines and how they link property, power, and capital in a perpetual pulsation of accumulation (profit and growth). Such a definition can be leveraged to help develop effective alternatives. Therefore, my definition of capitalism comprises three doctrines: proportionality, dispossession, and hierarchies.

Growth is at the center of the three defining doctrines of capitalism: proportionality, dispossession, and hierarchies. (author’s figure)

Proportionality refers to the fact that one share, as opposed to one human, equals one vote in corporations. Dispossession refers to the appropriation of property, with or without consent, to transform it into profit-making capital. Hierarchies refer to the unelected managers and executives in corporations and other status-quo organizations. Abolish these 3 doctrines and you abolish capitalism as we know it, in its corporate-driven sense.

The most common understanding of capitalism is that it refers to free markets and private ownership of the means of production. That is true, but a longer view, encompassing the origins of capitalism, reveals that markets long preceded capitalism.

Starting in the 16th century, social relations between the propertied and landless classes in the United Kingdom evolved into today’s capitalism. The doctrines of proportionality, dispossession, and hierarchies codified into law the links between property, power, and capital (the means of production). These doctrines continue to govern our economic system, with the growth imperative at its core.

Abolishing capitalism would require phasing out the three doctrines. But what’s the best approach?

Circles of Thinking

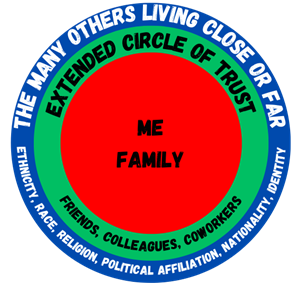

When considering the bottom-up versus top-down dilemma, it is helpful to conceptualize human thinking as falling into three overlapping circles. Bottom-up-ers think change must start in the red circle and push outward. Top-down-ers think change must start in the blue circle and push inward.

In which of these “circles of thinking” do you invest your energy for change? (author’s figure)

Revolutions are contextual. They are vectors with several axes: location, culture, and the material throughput of the economy. Each axis has unique tipping points and contributes to the relative prominence of each of the three circles of thinking. Strategies for reform should target each circle with a tailored narrative. North American and most European cultures are heavily anchored in the red circle, with people’s thinking driven by their own interests and those of their immediate families.

Red-circle reform requires dismantling some virtues, such as conspicuous consumption, to expose them as vices. Green-circle reform entails creating groups of trust for a common purpose, such as tenant unions and cooperatives. Blue-circle reform requires attacking capitalism on its turf, boycotting speeches, engaging in civil disobedience, and pressuring politicians. Ideally, change in any of these circles will spill over into the others.

Whether bottom-up or top-down, shifting culture is possible. From slavery to smoking, humans have changed their thinking and behaviors, often within a decade. Degrowth toward a steady state economy should be front and center as the solution to today’s polycrisis, from climate breakdown to colonialism and inequality. Degrowth is about limiting material consumption, but our freedom and security are at stake.

Why We Need Both Approaches

If you are in the top one percent globally, or the top ten percent locally, you should take it upon yourself to do some bottom-up degrowing. There is no excuse to accumulate more than $5 million in wealth (earned from wages, inheritance, or capitalist appropriation), or to seek income 5 times more than your local minimum. In Canada, that translates to a maximum gross income of $184,600 per year. We should leverage bottom-up approaches to socially stigmatize earning more than that in a year. We are riding a historical wave of opportunity to expose the “virtue” of excessive wealth for what it really is: a chokepoint on life.

However, there is a hard limit to the effectiveness of voluntary simplicity as a pathway to degrowth. For many people, voluntary simplicity means “homesteading” in the countryside. But a rural lifestyle is not necessarily more sustainable if one makes trips by personal [electric] car to hospitals, theaters, and libraries—common goods that we should not abolish.

The degrowth transition will require bottom-up and top-down limitations. As individuals, we should attempt to rework our entire ecological footprint, from what we eat to where we live, how we move, and what we buy. For the people who won’t voluntarily simplify, and for the growth-oriented infrastructure that is largely impervious to individual actions (the stock market, for example), we also need government intervention.

We’ll need every conceivable approach—bottom-up, top-down, and in-between—to save the things we love from the GDP bulldozer. (© ecoflight)

Governing bodies must justly ration production and consumption, using concepts like ecological footprint to ensure fair distribution for all humans. We need them to cap the extraction of natural resources and the end-use consumption of commodities like electricity. Governments must also facilitate the conversion of mega mansions into multi-unit buildings, for example, to ensure individuals’ bottom-up actions don’t lead to waste.

There is no single recipe to fight capitalism. Bottom-up is okay. Top-down is okay. In fact, the intersectional challenges we face call for a diversity of approaches. Some of these challenges are hyper local, such as drinking-water quality. Some are intercontinental, such as present-day colonialism. We need all hands on deck, whether you are drawn to a “simpler way” of life, union involvement, or political activism.

As long as they target the three core doctrines of capitalism, all fights are legitimate and desirable. We cannot remain stuck in the red circle of thinking. Neither can we remain stuck in the blue circle. The flow of thinking should constantly move from me to us and from us to me.

Vlad Bunea is a video essayist, essayist, and editor of the Sufficiency and Wellbeing Magazine.

Vlad Bunea is a video essayist, essayist, and editor of the Sufficiency and Wellbeing Magazine.

This makes a lot of sense – in my mind, I call it the “all of the above” approach to problem solving.

In particular when it’s hard to predict with certainty what will work best, it’s wise to have competing approaches at work.

This wonderful article got me thinking about examples of people who have managed both bottom-up and top-down. Ralph Nader came to mind. He does not own a car, his clothing is that of a “conscientious objector to fashion”, he lives on $25,000 a year and donotes a large perecentage of his stock holdings to non-profit causes. At the same time, his activism enabled him to play key roles in legislation (top down) in the Clean Water Act, the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency, OSHA, FOIA and other breakthroughs. Neither of the two major political parties can come close to what he accomplished. Finally, Nader has remained non-sectarian and still does a podcast, now in his nineties. I am sure we can come up with other people who have been successful at both bottom-up and top-down.

Nature is telling us that 8 billion people are not sustainable and overshoot is a threat to humanity. Women given the opportunity to choose will have fewer than replacement children and the overshoot will be corrected.

Think about

Marandi

Mamdani

and now

Francisco Albanese (New Sophia Loren)

They talking somewhat of similar issues but wildly different approaches.

I believe sustainability – operating within the ecosphere’s regenerative and waste assimilative capacities – can only be achieved with a ‘top-down’ approach (mutually agreed upon mutual coercion) in the form of ‘caps’ or quotas based on Herman Daly’s very simple principles: (1) extract renewable resources no faster than they can regenerate; (2) extract non-renewable resources no faster than they can be replaced by renewable resource substitutes; and (3) generate waste no faster than waste sinks can absorb them. ‘Bottom-up’ approaches can reduce the throughput-intensity of economic activity (more efficient allocation) but can’t limit the volume of economic activities in the same way as throughput caps. Hence, unlike caps, they cannot prevent the onset of the rebound effect of Jevons’ Paradox.

If a country’s rate of throughput currently exceeds its biocapacity, the caps should be tightened over time, which would lead to degrowth until settling at an ecologically sustainable steady-state economy. Thus, any required degrowth needs to be imposed from above. It cannot be guaranteed from below.

A complex, technologically sophisticated economy cannot function without modern money/taxation and modern markets. However, they cannot function effectively (equitable distribution and efficient allocation) without a currency-issuing central government using its fiscal powers in an appropriate manner (including ignoring its irrelevant budget bottom line) and without central governments heavily regulating modern markets, which again requires top-down policies. Once these have been implemented, we can then allow bottom-up methods to efficiently allocate a sustainable rate of throughput to society’s benefit. Macro (top-down) control and micro (bottom-up) flexibility.