Challenging the Pro-Growth Market: Mark Carney’s Reith Lectures and the Need for a Radical Approach

by James MacGregor Palmer

Mark Carney, coming around but still a green growther. (CC BY-SA 2.0, World Economic Forum)

“Society won’t settle for worthy statements followed by futile gestures. It won’t settle for countries announcing plans in Paris five years ago for 2.8 degrees warming, far too high, that they don’t even meet. Society won’t settle for companies that preach green but don’t manage their carbon footprints, or financial institutions who can’t tell us whether our money is on the right or wrong side of climate history.”

These are not the words of an environmental activist, Green politician, or concerned steady stater. These are the words of a neoliberal former investment banker. A former governor not only of the central bank of his native Canada but also the Bank of England.

Mark Carney is the latest “significant international thinker” to be invited to deliver the BBC’s flagship annual lecture series: The Reith Lectures. In his four-part series, entitled “How We Get What We Value,” Carney eloquently identifies many of the problems with the model on which many of the global West’s and North’s economies are based. But the solutions he proposes fall woefully short, offering more of the same when the changes we need will have to be more radical at this stage.

The Deity of the Market

Carney begins his first lecture with a story, spinning a narrative to shine a light on a fundamental truth:

At some point every North American child learns a sentimental story by an American writer, O. Henry. It tells the tale of a newlywed couple one Christmas Eve. Penniless and frantic to find a gift for her husband, Jim, Della sells her long tresses of hair and uses the proceeds to buy a chain for his beloved watch. When they are reunited for dinner in their small apartment […] she discovers that Jim has just sold his watch to buy a set of combs for her hair. He has no watch, she’s cropped her hair, and although they are left with gifts that neither can use, they realize how priceless their love really is. Now, when I first heard that story, it had its desired effect. I momentarily forgot about the hockey stick I’d been coveting and thought more about my mother’s need for new slippers. It’s in the giving that we receive.

Henry’s The Gift of the Maji, Carney laments, teaches a moral truth that has been eroded from our collective conscience as neoliberal values escape the confines of the market and seep into our social lives. Delivering his lectures in Glasgow, the birthplace of capitalism’s founder Adam Smith, Carney argues that our current economic hegemony is a far cry from what Smith envisioned. While Smith warned of “the mistakes of equating money with capital and divorcing economic capital from its social partner,” we have blurred the lines between economic and social value since the rise of Thatcherism in the UK and Reaganomics in the USA. The pandemic has illustrated the ugly effects of this conflation in horrific detail. If we do not learn our lessons, the climate will be an even less forgiving teacher.

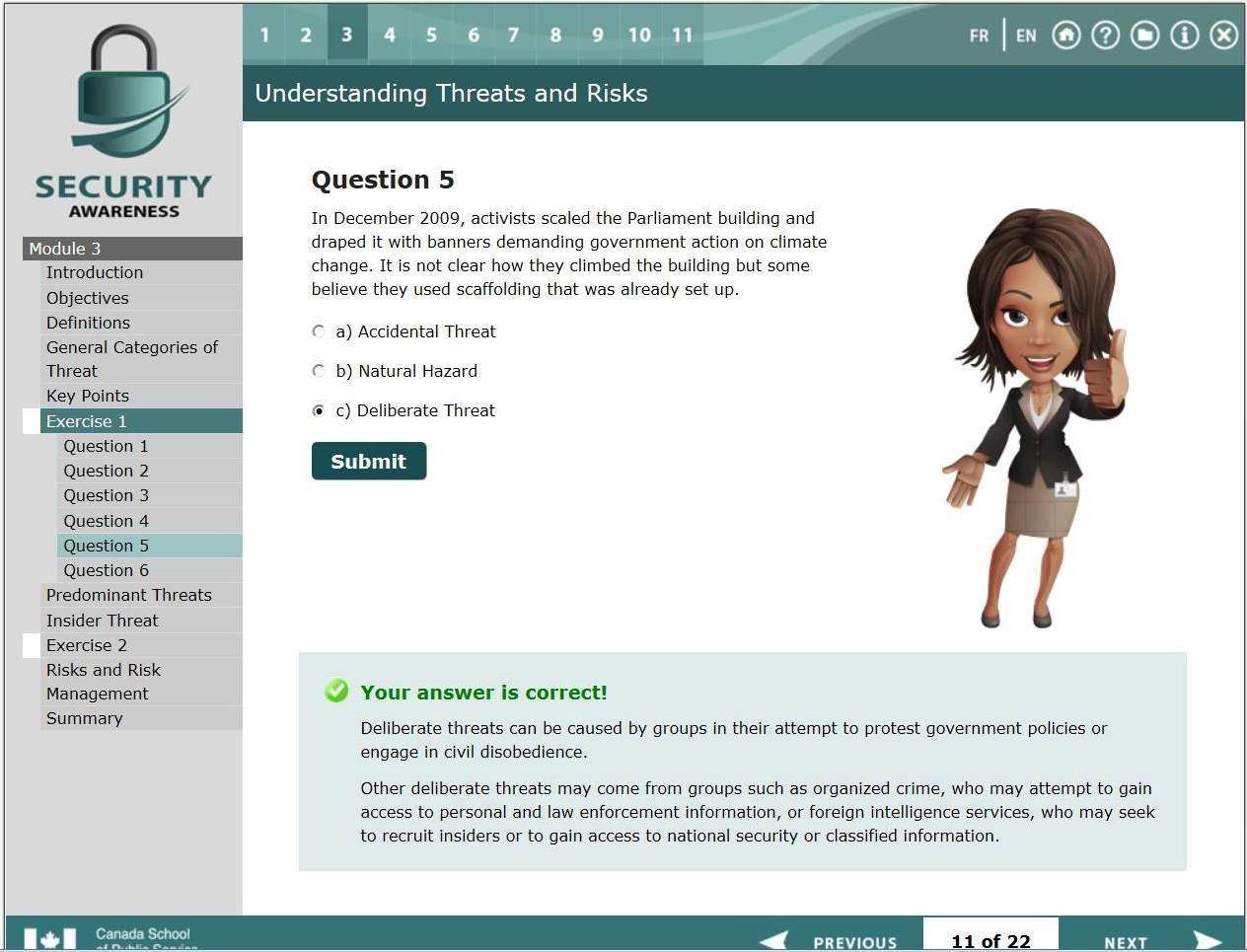

Carney provides a rather terrifying insight into just how powerful the market has become. He recounts how, upon joining the G7 in the early 2000s, he discovered an environment where “policymakers like [himself] had nothing to tell the market—they only had to listen and learn.” This mindset led to a poignant observation from Carney’s colleague Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa: “When we grant an entity infinite wisdom, we enter the realm of faith.”

If the market has become a deity, then it is not a benign one. When we remove the agency of policymakers and replace it with blind faith in the entity of the economy, we forget that it is an entity we constructed. It must work for us, or it does not work at all.

The Incentive of Civic Duty

The intrusion of market values into the moral sphere is the core problem that Carney identifies, and it is one of the key issues that a steady state economy would aim to set straight. However, Carney also offers insight into an interesting phenomenon that may hold the key to gaining mainstream acceptance of steady-state ideas.

Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa: “When we grant an entity infinite wisdom, we enter the realm of faith.” (CC0, Stephen Jaffe)

Despite the increasing inference of economic value on noneconomic activities, devaluing them when there is a lack thereof, monetization of an activity can actually decrease its perceived value. Carney raises several examples. In the UK donating blood is a voluntary activity, whereas in the USA blood donors are compensated, and the former yields far greater participation. Fines for late pickups from childcare are viewed by parents as simply the financial cost of being late and not as appropriate chastisement. And in a study (which Carney sadly does not cite), children were shown to be more incentivized to raise money for charity when they were not paid for their troubles. In other words, a sense of civic duty is a powerful motivating tool. But when we allow the market to infringe upon civic life, it ascribes financial value to civic actions, and slowly we begin to see only the financial value and not the intrinsic one.

This logic can be mapped onto the climate crisis, though Carney stops short of doing so. In a consumerist society, the environment is framed as an asset to be exploited. If it is worth protecting, then we only protect our ability to extract value from it in years to come. This is a long-term financial motivation which, as Carney argues, is inherently weak and will always be superseded by the short-term financial incentive to exploit the natural world as quickly as possible, no matter the damage caused.

Advancing the steady state economy fundamentally changes the way we frame the environment, and we must begin changing that frame before we have any hope of achieving our economic goals. Framing the environment as intrinsically valuable—a social good or even a good thing in its own right rather than merely an economic good—is essential in order to incentivize people to protect it. Once we begin to see protecting our environment as a civic duty—to both the environment itself and our fellow human beings—the incentive is far greater. But in order to create this sense of civic duty, we must first redefine the lines between economic and social value.

The Solution Is Not Tinkering

Though the problems Carney identifies in his first lecture are sound, the solutions he identifies in his fourth fall short of the mark. He recalls the moment he sat in the UN General Assembly and heard Greta Thunberg stand up and address the room:

“You’ve stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words. And yet I am one of the lucky ones. People are suffering. People are dying. Entire ecosystems are collapsing. We are in the beginning of a mass extinction, and all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth. How dare you!”

Greta Thunberg to the Mark Carneys: “…all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth.” (CC BY 2.0, European Parliament)

Whilst Carney acknowledges the “power of Greta Thunberg’s message,” he refuses to accept her analysis. “The market is not the answer to everything, but it can play a critical role in solving many of humanity’s greatest challenges,” he argues. “Continued growth isn’t a fairy tale—it’s a necessity.”

Carney’s view is that net-zero carbon emissions will only be achieved by manipulating the market to favor businesses who are environmentally conscious. By forcing businesses to work toward carbon neutrality by making it more profitable for them to do so, the climate crisis could be solved whilst growth continues to soar. Mark Carney wants to have his cake and eat it too.

In making this argument, Carney completely undermines his analysis from previous lectures. What his solution amounts to is a financial incentive, the likes of which he laments the limits of earlier in the series. It is a far easier fix than initiating a fundamental hegemonic shift, but it is also far less sufficient. If financial incentives are weaker than civic ones, why would we not aim for the latter?

Carney seems to also assume that the only issue with endless growth is that it causes carbon emissions. This is far from the truth. A society centered around GDP growth can make our vehicles less efficient, our commutes more stressful, our work more time consuming, our healthcare more expensive, our family time more scarce, and our civic calling short-changed. In other words, not only the environment but our personal and social wellbeing suffers from the obsession with GDP.

When it comes to the environment, the climate crisis is not just what we’re putting into our atmosphere, it’s what we’re taking out of our ecosystem. A carbon tax would do nothing to address the exploitation of other natural resources, the destruction of habitats, and the attitude that everything on the planet is ours for the taking. To follow Carney’s lead would be to leave the clock ticking indefinitely, solving one crisis but awaiting the inevitability of the next.

The climate crisis, just like our wellbeing and inequality crises, will not be solved by economic tinkering. In identifying that the structure of our economies has a role to play, Mark Carney has come halfway to realizing what is required. Old habits die hard, but it is time for him to let go of the notion that “the market knows best.”

James MacGregor Palmer is a master’s student at the University of Stirling studying international journalism.

James MacGregor Palmer is a master’s student at the University of Stirling studying international journalism.

Can the market solve the climate crisis? I think this is absurd question. There is no way “the market” would ever solve the climate crisis because it is privately controlled for profit by greedy people. That is why we need to nationalize the money and put a demurrage fee on it. The monetary system concentrates all the money to the wealthiest. They use it to dominate the markets for personal gain. They don’t have the mental or moral capability for addressing the climate catastrophe.

Yes, this is my point. An entity that is so set up to benefit those at the top, no matter the detriment to the environment or those at the bottom, cannot just be tinkered with in the hope of solving such a monumental threat. Thanks for your comment!

As I was reading, I was imagining the author as being a wise emeritus. What a surprise I had when I arrived at the end to see this analysis from someone much younger. A very well-written piece. And, not being previously aware that Carney was the Reith lecturer this year, now I will have to listen.

Thank you for your kind words! The lectures are definitely well worth a listen, some interesting points raised even if I disagree with his conclusions.

I’ve listened to two of the four, now. I was struck, during the Q&A, by how introspective can be the tone of those (particularly former Tory ministers) when looking back. The Teflon suits go on as they, essentially, imply by way of the use of the 3rd person that they played no part in the lead-up to the crisis. All very serious — mmm, yes, harrumph, harrumph — in that Churchillian British sense while directing the blame elsewhere whilst in solemn conversation.

Something else that Carney mentioned early in the second lecture was a brief anecdote from his time at Goldman Sachs where someone he respected said that “if something doesn’t make sense, it doesn’t make sense. Run away, if you don’t understand it.” That strikes me as suggesting, perhaps disingenuously, that Goldman is lacking in agency and, further, played no part in the leadup to the crisis. In my opinion, Goldman doesn’t follow on these questions, it leads. It controls. Matt Taibi’s classic description, “a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money” wasn’t earned from meekly following and playing by the rules set by others.

I listened to all four lectures and would suggest that James’ critique of Carney’s supposed obsession with GDP growth is not justified. First, there is no evidence of such obsession. Second, he talks (in the 4th lecture) about growth in the context of growing economic activities that are needed to overcome climate change and de-growing what belongs to the “old” economy. Steady-staters tend to mistakingly believe that all growth is bad, thereby ignoring that the economy is and should be dynamic — only net growth should be zero, at least in rich countries. In fact, I have yet to see an analysis that deals with the practical problem of how such zero net growth can be achieved.

Each of Mike Carney’s lectures contains much wisdom (besides a few bloopers). Central to his thesis is the very non-neoliberal proposition that “values” must trump market value — solidarity, fairness, responsibility, compassion. Re climate change, he posits a commitment to “net-zero by 2050” as a goal that supersedes any market considerations. (Apparently 126 countries have now formally committed to this goal.) I.e., trade-offs (economy vs. environment etc.) should not be a valid consideration.

I didn’t seem to recall a portrayal of Carney as having an “obsession with GDP growth.” So I checked again, and indeed, the author portrayed Carney as being somewhat confused and or waffling about the sustainability and desirability of growth. That’s far from “obsessed.”

The author did state “not only the environment but our personal and social wellbeing suffers from the obsession with GDP,” but he wasn’t portraying Carney as having such an obsession.

Then, too, the key word here is “obsession.” Carney ultimately did revert to his pro-growth stance; given the context, some folks might view that as a sign of obsession. I wouldn’t. I tend to save that word for obvious growth obsessors such as Donald Trump. See for example https://www.steadystate.org/democrats-trump-underbelly-of-growth/ .

Finally, we say and write all the time at CASSE that some sectors will expand while others decline in a steady state economy. Of course. Achieving that is not rocket science, and we have plenty of practical policies proposed toward that end already. The bigger challenge at this point is building the awareness of the need for these policies, thereby achieving the political viability thereof. The awareness building and political advancement go hand-in-hand with finer tuning of the policy framework and instruments.

The earth and the total energy input into it are finite so basic physics shows that growth on the earth cannot continue forever, i.e., a finite input (the daily energy input from the sun) cannot result in an infinite output. That does not even take into account the second law of thermodynamics, that order becomes disorder (or ‘rust always wins’). In practical terms this means that everything humanity has built is gradually falling apart. There will also be a point at which the air (too much methane and carbon dioxide leading to increasing greenhouse effect with measurable increases in temperature, loss of permafrost and a positive feedback loop that is accelerating that damage), water (water tables dropping, lakes (much of one of the Great Lakes has undrinkable water), rivers (whales dying in the St Lawrence River) and oceans showing visible damage already (algal blooms, small country -sized floating masses of plastic and more) and land (desertification, mountain top removal) are dangerously polluted, due to the ‘economy’. Ongoing economic growth will only increase the damage to our earthly home by increasing the necessary inputs to maintain economic growth (causing abuse of land, air and sea to obtain the resource inputs required to maintain, let alone grow, the economy. The only answer is a combination of reducing the world’s population, redistributing wealth more fairly from rich people and countries to poor people and countries and education of people with goal of teaching an appreciation of nature, reducing consumerism (the best things in life are free (or should be)-friends, family, air to breathe, water to drink and food if home grown), and encouraging our support for one another.