COP15: The Good, the Bad, and the Smugly

by Brian Czech

On a scale of one to ten, COP15—the UN Biodiversity Conference in Montreal last month—was a solid five. That may not sound like a ringing endorsement, but it represents significant progress from prior COPs, which dabbled along in the one or two range for the better part of three decades. The progress was evident from the start, when UN Secretary General António Guterres kicked off the conference by noting, “With our bottomless appetite for unchecked and unequal economic growth, humanity has become a weapon of mass extinction.”

General António Guterres delivered the metaphor of the decade: the human economy as a “weapon of mass extinction.” (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, UNFCCC)

That was good.

Also promising were several sessions quite focused on the conflict between economic growth and biodiversity conservation. The problem was, these sessions weren’t official negotiations of the parties (nation-states) to the Convention on Biological Diversity. Rather, they were “side events” strewn about the official negotiations.

That—the marginalizing of these excellent events—was bad.

Finally, a few key individuals fell short, in terms of telling it like it is about the conflict between economic growth and biodiversity conservation. They say they don’t “believe” there is a conflict. Such an outdated, unscientific “belief” is gradually being relegated to a sort of smug cohort that opines on such matters with nary a background therein.

Let’s explore some examples of the good, the bad, and the smugly from COP15.

The Good

A metaphor for the ages was born in Montreal. When Secretary General Guterres referred to the economy as a “weapon of mass extinction,” he raised the bar for all future COPs as they wrestle with exactly how we get sustainable. How do we conserve biodiversity? How do we stabilize our greenhouse-gassed climate? How do we protect the planet for indigenous and non-indigenous people alike? It certainly won’t be by employing the “weapon of mass extinction.”

The “weapon of mass extinction” (GDP growth) provides such an apt metaphor, it’s tempting to advance its also-apt acronym: WOME. WOME is coming; WOME is here. WOME pulls the rug out; it’s WOME we should fear.

Surely the COP milieu can handle one more acronym. Acronyms filled the air, agenda, and signage in Montreal, where the UN, CBD, and PRC were especially prominent. I gave a talk in a side-event enclave marked, “COP15 – CP/MOP10 – NP/MOP4,” discovering later that the full name for the cumulative event in Montreal was actually acronymized as “OEWG 5/CBD COP15/CP-MOP10/NP-MOP4.”

No, the acronym soup wasn’t particularly digestible for the unfamiliar, but some of the ingredients were nourishing nonetheless. SNAP, for example—the Société pour la Nature et les Parcs du Canada—was forthright and firm in describing the fundamental conflict between economic growth and biodiversity conservation.

SNAP was the organizer of “Side Event #4362,” a panel session held on December 8 in one of the medium-sized auditoriums of the convention center. The title was “Joining the Dialogue: Solutions to the Underlying Causes of Biodiversity Loss.” By the time it was kicked off by Alain Branchaud, SNAP’s Directeur Général, the auditorium was packed with approximately 400 attendees. The session was focused as advertised on the underlying causes of biodiversity loss, and Branchaud wasted no time in tapping into Guterres’s metaphor. He elaborated eloquently and explicitly about the conflict between economic growth and biodiversity conservation.

Here’s looking at you, Mayor Plante and Grand Chief Gull-Masty, for steady statesmanship. (CC BY 2.0, UN Biodiversity & CC BY-SA 4.0, Erbvdat)

Branchaud was a steady stater par excellence, setting the stage so compellingly that none of the other panelists could overlook the conflict. Not that many of them would have. Oscar Soria of Avaaz (with its 70 million members) and Mandy Gull-Masty (Grand Chief of Quebec Cree) were right on board. Valérie Plante (Montreal’s mayor) and Steven Guilbeault (Canada’s Minister of Environment and Climate Change) seemed quite aligned as well.

When an opportunity like that materializes, and when good people have put themselves on the line for the sake of the inconvenient truth, I think steady staters are practically obligated to participate as supportively and synergistically as possible. Thus, in the open forum, I shared a quickly concocted vision of steady statesmanship, suggesting it start with Mayor Plante in tandem with Grand Chief Gull-Masty. The idea was simple: With the substantial PR tools at their disposal, the mayor and the chief would announce to the broader public their mutual concern with Montreal’s sprawling growth. Was growth still a wise thing at this point in history? What good was it doing? Conversely, what was it harming? How much “illth” was it causing?

The mayor and chief would propose instead a transition to a steady state economy. The transition would be gradual and reflected in budgets, tax codes, planning documents, and ongoing oratory leadership. The metropolitan and tribal governments wouldn’t be micromanaging the economic activity of citizens, but they’d cease and desist from macroeconomic stimuli, and lead businesses and consumers to conserve.

Such a campaign would resonate strongly and would naturally (and strategically) spread to Quebec at large, then into the Canadian federal government, ultimately emanating into international affairs. It would amount to the first clear episode of steady statesmanship in history.

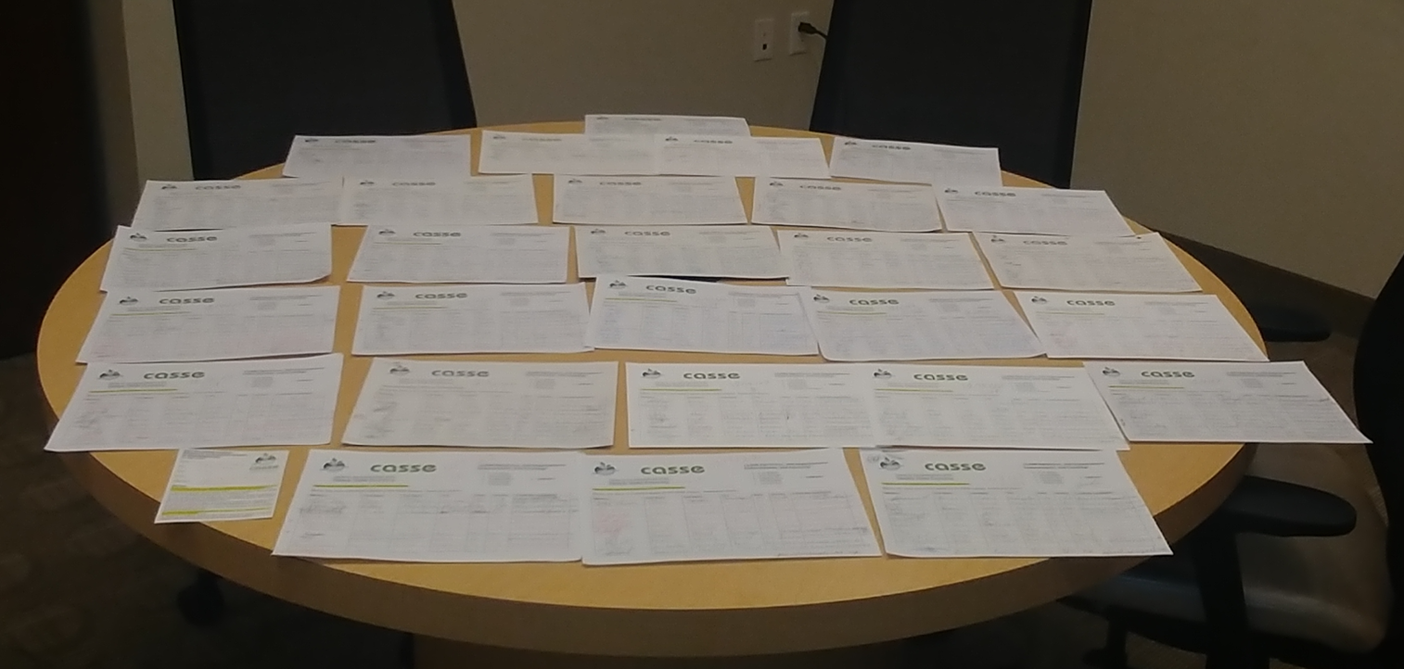

The audience seemed energized by such a vision, and the mayor promised to consider it. Shortly after the session, Gull-Masty signed the CASSE position on economic growth, as did Soria. If Mayor Plante follows up, “Side Event 4362” could go down as the best thing to come out of COP15.

The Bad

WILD was another presence at COP15. And WILD wasn’t bad, actually. In fact, WILD was one of the best of the good.

“WILD” (short for the WILD Foundation) is capitalized not as an acronym but out of sheer emphasis. Led by Amy Lewis, this organization appreciates and advocates for the wild—wilderness, wildlife, wild nature—like no other. WILD’s energy and effectiveness was felt in a number of COP15 venues and events. One was a panel session on December 10, led by Lewis, called “Let’s Talk about Half: Delivering Effective Conservation to Halt the Sixth Mass Extinction.” Lewis and her fellow panelists were some of the most vocal opponents of the “30 by 30” deal ultimately adopted at COP15. Pursuant to 30 by 30, nearly all the parties pledged to protect 30 percent of their lands by 2030, whereas Lewis and WILD fought for 50 percent with sound science and vivacious verve.

Too bad one of the best panels at COP15 was a “side event.” (Far left: Amy Lewis, WILD Foundation. At the mic: Julia Jackson. Credits: CASSE.)

Lewis herself gave one of the most impassioned speeches I’ve ever seen. Outside of memorial events—funerals for example—you rarely see a speaker shedding tears, but the deep-thinking WILD leader was moved by the plight of non-human species, and her sincerity was palpable. Like Branchaud before, she cut to the chase about the conflict between economic growth and biodiversity conservation. Most of her panelists were quite good at the same, especially Julia Jackson, a wide-ranging environmental leader with similar impact as a speaker. Surely no one who attended the session will ever forget it.

The “bad” part about it (the only bad part) was that it turned out to be, again, a “side event,” and a much smaller one than the one led by Branchaud. Perhaps a hundred people attended, whereas it should have been witnessed by thousands.

The bad of COP15, then, was that the conflict between economic growth and biodiversity conservation was largely sidelined, shrugged off and shoved under the rug by the parties per se. Not enough paradigms were shifted, because not enough minds were exposed, notwithstanding Guterres’s one-off reference to the “weapon of mass extinction.”

The Smugly

While WILD wanted to protect 50% of the planet for biodiversity, the World Bank was concerned with a different 50%. They wanted to “act now for a nature-positive world” because 50% of global GDP “depends on biodiversity and ecosystem services.”

The concept and its application were as flawed as a factory second. It must be obvious to anyone with a mouth, stomach, or lungs that the “other” 50% of global GDP also depends on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Humans can’t even exist without the non-human variety of life (biodiversity in other words); the plants and animals that provide or comprise the proverbial food, clothing, and shelter, including literally all food.

As for ecosystem services, where would we even start? Suffice it to say: Want to breath? Must have plants. There’s no “50%” about it.

Next, the World Bank twisted their concept into the notion that economic growth and biodiversity conservation go hand-in-hand. It’s long been a common error of amateurs dabbling in conservation. The fuzzy, fallacious thinking is to the effect, “Biodiversity is valuable natural capital, producing goods and services, so if we get better at protecting it we can produce even more goods and services, growing the economy in the process. See? There is no conflict between growing the economy and conserving biodiversity.”

It was precisely to avoid such blunders that I penned a primer on economic growth and biodiversity conservation for COP15 conferees. But CASSE is a tiny non-profit organization, not an environmental behemoth like the World Wildlife Fund (long a muddler on the relationship between growth and conservation). Guess which one was represented at COP15 by one individual pamphleteering out of a rolling suitcase, and which by an army of staffers manning the “Nature Positive” pavilion at COP15, the latter becoming a big tent for the win-win rhetoric that “there is no conflict between growing the economy and conserving biodiversity.”

CASSE’s COP15 flyer came in postcard form. Nearly 2,000 circulated.

So it was unsurprising to run into numerous win-win rhetoricians at COP15, including none other than the CBD Executive Secretary, Elizabeth Maruma Mrema. In a press briefing on December 12, when asked if the parties would finally be recognizing the conflict between economic growth and biodiversity conservation, Mrema opined that she didn’t “believe” there was such a conflict. It was the rock-bottom moment of COP15.

Mrema’s audience was crucial for the success or failure of COP15. While it wasn’t as big as the SNAP audience, it was much bigger than the WILD audience. More importantly, it comprised primarily news reporters and journalists from all over the world. The press briefing was a chance to get some ecological economics (and common sense) into the mainstream, global media. Instead, if anything, the opposite happened, with outlets such as the Financial Post delivering nothing more than a muddled account of the exchange.

Yet under the heading of “Smugly,” Mrema is hardly the quintessential offender. She seemed sincere with her answer, and probably hadn’t yet encountered to the basics of ecological macroeconomics. That’s a “bad” we can attribute to prior COPs.

Mrema wasn’t smug, in other words; just wrong.

Unfortunately, that’s not the impression given by some of the win-winners operating under the Nature Positive Pavilion. On December 16, a two-session mini-series called “Nature’s Moment” was sponsored by the World Bank and moderated by Anita Anand of the BBC. I’d done my job prior to the series, distributing CASSE’s COP15 flyer, a postcard asking, “What is biodiversity conservation in policy terms?” and answering, of course, with “a steady state economy.”

Some of the panelists from “Nature’s Moment” including (left to right) KM Reyes, Anita Anand, Satyendra Prasad, and Mari Pangestu. (Credits: CASSE.)

Anand received a copy prior to the event, as did Mari Pangestu, the Managing Director of Development Policy and Partnerships at the World Bank. In fact, the three of us chatted briefly about it just minutes before the event. Yet minutes later, Anand inexplicably contorted the topic, asking, “Is it fair to say that there is still very much the notion out there that biodiversity is something that comes at a net economic cost, rather than a net economic benefit?”

Anand’s fuzzy but loaded question was bound to produce a fuzzy answer. It was like substituting the simple question, “Does two plus two equal four?” with “Is it fair to say that there is still the notion out there that a three coming with a one plus a zero coming with a two leads to a four?” Who’d care about whether there was a “notion out there,” especially when the subject of the “notion” wasn’t clear to start with? And how was someone on the spot, miked up for the panel and recorded for posterity, supposed to reply to such a loaded prompt?

Anand could have simply asked, “Is there is a conflict between economic growth and biodiversity conservation?”

Not that Pangestu would have answered correctly, anyway. “I think you’re right,” she said about the fuzzy question. “I think people don’t see, I mean at the moment, there is kind of this misperception that addressing biodiversity or climate change is a cost. Actually investing in nature and climate is about development; it is about the opportunity for development and growth, and it’s not a trade-off.”

The discussion was clear as mud and an embarrassment to the conservation community. Pangestu’s background, prior to the World Bank, was as trade minister for Indonesia. Anand’s two books included a novel about a princess and a history of the Koh-i-noor diamond. Yet in their self-assurance about growth and conservation ambling along hand-in-hand, they came off as smug as Donald Trump discussing Mexico with Tucker Carlson.

Hundreds of signatures on the CASSE position from COP15. (Credits: CASSE.)

Contemplating the leadership and moderation of “Nature’s Moment” brought back memories of Confessions of an Economic Hit Man. I glanced about furtively to see if John Perkins might be slinking around behind the stage, pulling strings and pushing levers. Who else in the bowels of the OEWG 5/CBD COP15/CP-MOP10/NP-MOP4 would have ever positioned Anand and Pangestu thusly?

Yet even in this smugly corner of COP15 there were signs of steady-state progress. The one panelist who was actually an environmental expert, Tony Juniper, took one look at the CASSE position on economic growth and signed on the spot. So did the ambassador from Fiji, Satyendra Prasad. My guess is that most of the panelists would have concurred with the CASSE position, explicating the fundamental conflict between growth and conservation, and that Anand and Pangestu were anomalies despite their leading roles in the event.

Similarly, of the hundreds of individuals I spoke with in Montreal about economic growth and biodiversity conservation, the vast majority got it about the fundamental conflict. Many had the attitude, “Of course.” Some of them were advanced students of ecological economics. Others were just smart, experienced professionals who expressed their frustration with the win-win rhetoric of politicians and World Bankers.

Far from a “notion” that “still” exists, the scientifically rooted reality of the conflict between growth and conservation is finally sinking in across the board.

Brian Czech is the executive director of CASSE.

Brian Czech is the executive director of CASSE.

This is highly encouraging news! Brian, I think you (and any other steady staters at the conference) have done yeoman work. The CASSE flyer, condensed enough to be approachable by a casual reader (and maybe get a few people thinking), and the signatures gathered… excellent stuff.

I’ve gotten used to the idea that humans are incredibly, maddeningly slow to understand that the future really is shaped by actions today, and that the future really will come along and “hit ya in the backside”. We see this with individual health – hundreds of millions of people know full well they theoretically should not eat junk, but they do it anyway… until the consequences hit.

I can’t think of any change in human civilization that came as quickly as it should have, in hindsight. Our species is blinkered. Knowing that, the right thing to do is not let frustration gnaw at us too much. We’re starting to see a bit of movement, and these things can start moving very quickly after a certain point. It’s probably not soon, but I’m encouraged, and grateful.

Excellent post. Insightful and informative.

Hear, hear.

Thank you for the inside view, and the proof that some members of our species are blinkered, but a growing number of others are not. It is to be expected that the leading members at such events events are anomalies and hold their positions because the balance of power has not yet shifted to the side of the majority. Takes hard work to get 100s of signers. Bravo.