Introducing the Sustainable Trade Act

by David Shreve

What are supposed to be the advantages of the free-trade consensus that has emerged in the last century? Yes, innovative technologies and techniques have made their way around the globe. The diffusion of digital communications, managerial technology, advanced materials engineering, and efficient shipping techniques are but a few prominent examples. The openness and complexity of the global trading system have facilitated this diffusion.

Global trade has increased dramatically in the last half-century. (HippoPX)

Additionally, trade based on “comparative advantage” has modestly increased global economic efficiency. A nation’s producers have a comparative advantage when they can produce a good or service at a lower opportunity cost than another country’s producers. Theoretically, every country focusing on the goods and services it’s “best” at producing increases efficiency. This efficiency can benefit consumers in developed and developing economies. It has been a key factor, for example, in the suppression of inflation.

Deep trade relations are associated with international peace. Commercial partnerships often remind us that cooperation yields more benefits than transactional, “winner-take-all” belligerence. For example, an expanded trading relationship catalyzed many Sino-American connections and mutual dependencies over the last thirty years.

“Free-Trade” Pitfalls

Despite these modest advantages, associated with comparative advantage and global efficiency, free trade is subject to forces that expand its scale beyond sensible and sustainable limits.

Global trading networks operate on a finite planet. They can easily obscure the environmental impacts of consumption, and thus limits to growth. Developed nations, in particular, use international trade to borrow biocapacity from developing nations. This relationship is reinforced when international institutions encourage countries to “develop” by ramping up exports. These exports are heavily represented by primary products in extractive industries.

Too much trade still depends on iniquitous extraction in developing countries. (CC BY-SA 2.0, Jean-Marie Hullot)

Specialization in higher-value industries is often seen as the ticket out of the extractive-industry trap. “Vertical” specialization is when a country’s production of an intermediate good represents just one link in a larger supply chain. This is associated with increased wage equality in developing nations. However, these benefits have been uneven. Many developing countries in Asia have integrated into global value chains to their advantage. The same cannot be said of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Another free-trade pitfall is that when goods and services cross borders, environmental and labor standards are often compromised. Mobile capital still runs the age-old “race-to-the-bottom.” If given the opportunity, corporations often evade equitable taxes and ignore their dependence on government-secured stability. Corporations also tend to opt for less regulation, though regulation is ironically often the key to their survival.

Free trade—not to be mistaken with uncontrolled trade—cannot be sustainable, fair, or advantageous in an unfettered marketplace. Producers and nations with disproportionate power try to extract more value than they add. Idealized, beneficial free trade is almost always tethered to policy and planning.

But policy frameworks can be lopsided, predicated more on power than on equity or cooperation. Developing nations often need protection to scale up promising “infant industries” (though benefits from such protections have historically been inconsistent). They are frequently forced to safeguard domestic purchasing power with high interest rates or fiscal austerity imposed by developed nations at the International Monetary Fund and World Bank Group.

Without policies aimed at these habitual abuses, free trade is neither free nor beneficial.

A Fair-Wage Revival

Successful trade outcomes also depend vitally on sound policy within the borders of all participating nations. What Paul Samuelson called factor-price equalization—the tendency for increased trade income to benefit investors and workers—only materializes in the presence of robust domestic policies. It does not happen when corporations are allowed to marginalize and shortchange workers.

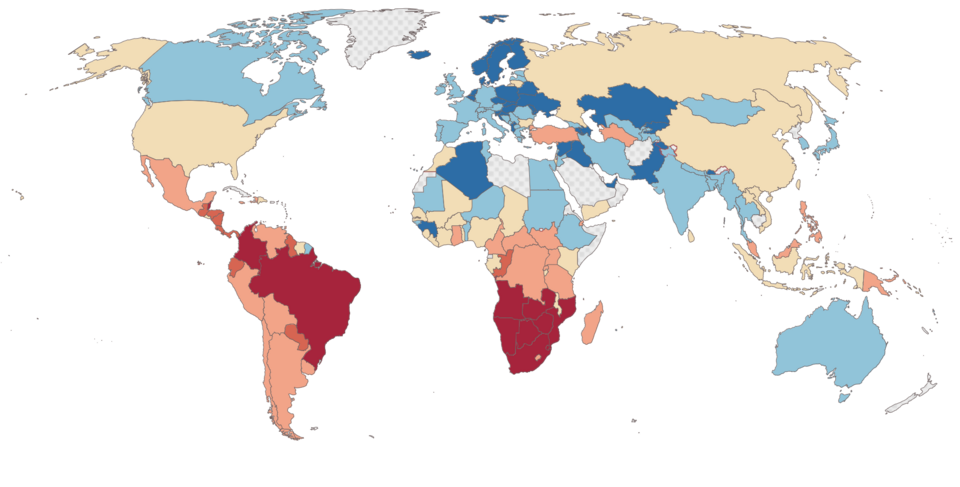

The latest available inequality score (Gini coefficient) for each country. The darker the blue, the more equal the society, and the darker the red, the more unequal. Inequality stymies factor-price equalization. (CC BY 4.0, World Bank Poverty and Inequality Platform)

Samuelson suggested that factor-price equalization emerges autonomously. It generally has not. Samuelson’s theory appeared to explain reality when he conceived it in the late 1940s. At the time, well-planned domestic economies—and international cooperation in the “free world”—were on the rise. Nations seemed eager to pay their workers fairly and share their newfound prosperity more broadly.

But this spirit of fairness and widespread prosperity has waned. It’s in need of an intentional revival. Without such a revival, the marginal income attributed to trade advantages will not flow to workers.

This fair-wage revival depends on much more than safety-net programs. Relocation assistance, temporary income security, and specialized training are useful but not equal to the task. It is far more important that nations adopt policies such as progressive tax systems and robust anti-trust laws. Universal public endowments in education, health care, transportation are also important. Sustainable international trade that benefits workers is impossible in their absence.

Sustainable Trade Requires Good Domestic Policy

To truly benefit from international trade, leading nations must approach it with a refreshed mindset and playbook. The United States must affirm that genuine comparative advantage and global efficiency are the paramount goals. Advantages generated by compromised environmental standards or the suppression of labor rights must be eliminated. U.S. negotiators must leverage trade agreements to marginalize kleptocracies, oligarchies, and the GDP fetishism that still preoccupies many nations.

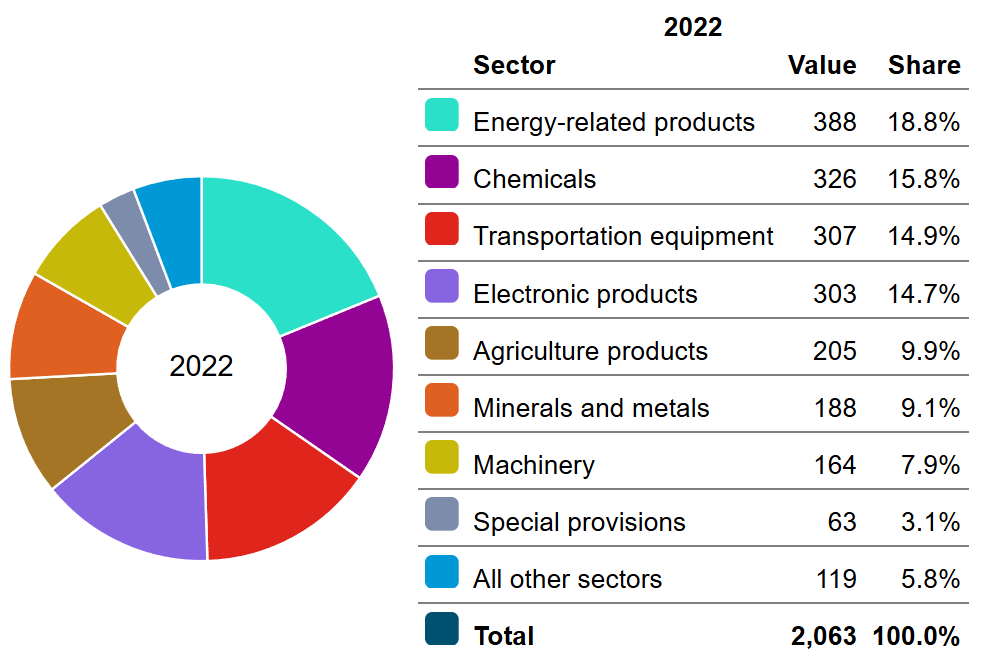

The United States is a major participant in world trade, but it’s a small part of the U.S. economy. (CC BY 4.0, Our World in Data)

No nation should obsess over its negative or positive terms of trade with any other single nation (or region). Done right, global trade will add modest efficiency and value to the economies of all trading nations. But this efficiency and value can only be measured usefully in the context of the entire trading system, the scale of which is every bit as important as its scope.

A fourth of nations engage in international trade with a total (rather than net) value greater than their national income. For the United States, however, international trade represents a smaller percentage of GDP than it does for any other major developed economy. This is thanks to unparalleled natural bounty. It is also thanks to domestic economic policies (progressive taxation, anti-trust laws, and social welfare programs) that have fostered a large middle class capable of generating its own thriving economy.

Properly planned—which entails appropriate scaling—international trade should offer modest advantages to many. But it will always depend upon, and pale in significance to, policies carried out within a nation’s borders.

Principles of Sustainable Trade

Energy products compose the largest share of U.S. exports. (Public Domain, U.S. International Trade Commission)

The most important principle of sustainable trade is ecologically sustainable scale. The first step to applying this principle is to determine which sectors of trade a) drive production beyond national ecological limits and b) enrich corporations and investors with few or no benefits for low- and middle-income citizens and little increase in overall economic efficiency. The next step is to set export and import limits in those sectors, using national biocapacity as a guide.

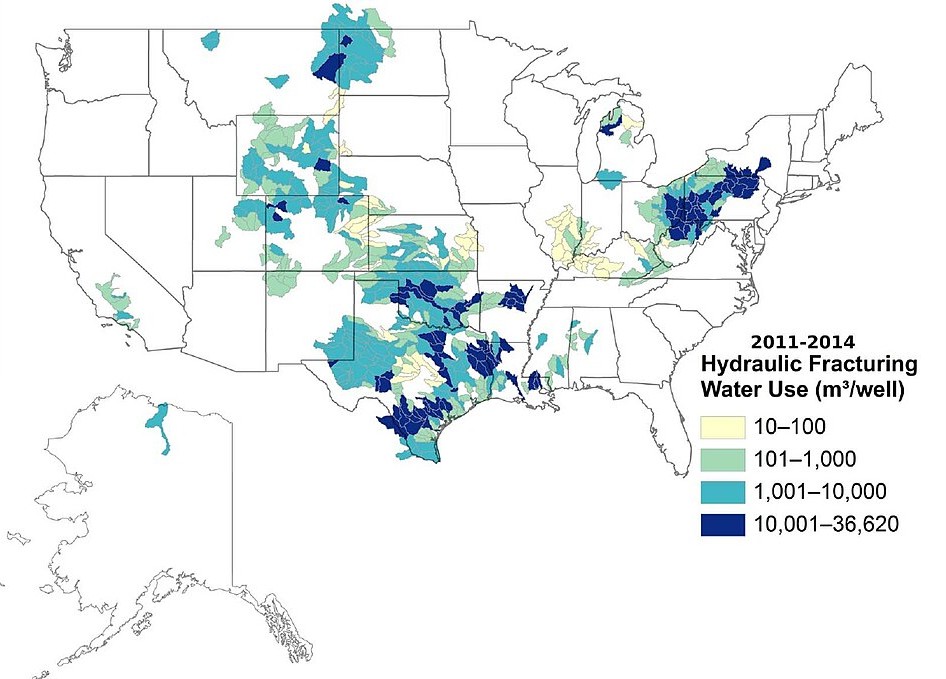

In the United States, marginal trading in the agriculture and fossil fuel sectors fits this description. Sector earnings often take precedence over environmental sustainability or trading efficiency. For example, the Trump administration’s push to expand natural gas exports, produced almost exclusively via hydraulic fracturing, displays a perversely intentional disregard of environmental impacts. Industry earnings are treated as paramount.

Another principle of sustainable trade is to allow more latitude for national support of goods related to less environmentally destructive technologies. Amid global ecological overshoot, there is every reason to allow more of what has historically been called “green protectionism.” The World Trade Organization (WTO) should prioritize the widespread benefits of cheaper and more plentiful renewable energy over the harm that “protectionism” could inflict on a few corporations.

Many nations hope to subsidize renewable energy product manufacturing. (CC BY 2.0, Oregon Department of Transportation)

A third principle of sustainable trade is that sometimes international trade is more efficient and environmentally sustainable than domestic trade. U.S. trade with its North American partners constitutes well over 30 percent of both its exports and imports, reflecting natural advantages. Exchanging goods and services with adjacent Mexican and Canadian regions is often more sustainable and efficient than many longer interior pathways. But none of this sensible exchange should rest on advantages tied to uneven environmental or workforce protections.

A final principle is that factor-price equalization is only possible with macroeconomic policy like wage floors tied to median income and labor-union organizing rights. At international forums like the WTO, the United States has an outsized influence on trade agreements and guidance for other countries’ domestic policy. As long as this is the case, the United States must exercise its power to promote the policies necessary for factor-price equalization. A more modest, sustainable, and mutually beneficial international trading system depends upon it.

Introducing the Sustainable Trade Act

As a feeder bill, the Sustainable Trade Act comprises ten sections. Sections 1–3 of the bill establish its short title, Congress’s findings and declarations, and definitions. Among the key findings and declarations is the assertion that no trade that compromises key environmental or labor protections should be promoted or enabled.

Pursuant to the principle of sustainable scale, Section 4 establishes long-term international-trade targets, expressed as a percentage of GDP. By 2040, international trade, including imports and exports, should represent no more than 20 percent of U.S. GDP, and by 2055, it should represent only 15 percent. The other provisions of the Sustainable Trade Act are designed to increase the feasibility of these targets by making trade less significant to U.S. prosperity.

Section 5 introduces export and import limits for major grains, seed oils, and meats for which exports exceed 20 percent of total U.S. production value or imports exceed 15 percent of consumption value. The Department of Agriculture’s Foreign Agricultural Service is tasked with setting the trade limits according to sustainable production levels. They are to determine these production levels based on the biocapacity of the United States and importing nations.

Water use and water pollution are big issues with hydraulic-fracturing production. (Public Domain, USGS)

Section 6 bans the export of oil and natural gas produced via high-volume horizontal hydraulic fracturing. Most U.S. oil and natural gas is produced using this method, which leads to groundwater and surface water contamination, air pollution, and climate change. Though all hydraulic fracturing—and all fossil fuel extraction—must eventually end, banning the excess production represented by exports is a good first step for our trade bill.

In the interest of speedier diffusion of renewable energy, Section 7 directs the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) to exercise its influence at the WTO by requesting exemptions from trade disputes for subsidized renewable energy products and services. The section lists seven products for exemption, tasking the Department of Energy with annual revisions.

To further encourage environmental goals, Section 8 directs the USTR and other trade-policy entities to increase U.S. participation in WTO “structured discussions” on environmental sustainability. This dovetails with Section 7 by prioritizing exemptions from trade barriers for environmental-protection subsidies in Article XX of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

Section 9 of the Sustainable Trade Act directs the USTR to promote stricter labor- and environmental-protection mandates at the World Bank Group for countries receiving loans and grants. This policy is focused on revenue adequacy, equity, and stability to encourage broader income sharing in developing nations. The proposed loan and grant mandates include commitments from recipient nations to a) establish a minimum wage no less than 60 percent of the median income, b) ensure the right to organize in labor unions, and c) enforce child-labor laws equal to or more protective than U.S. laws.

Section 9 also requires similar prioritization in the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement. It directs the USTR to propose amendments to the North American Agreements on Environmental Cooperation and Labor Cooperation. These amendments would “impose environmental regulations on all trading partners no less stringent than those enforced under existing U.S. law.” Similarly, they would ensure collective bargaining rights for all workers in participating countries at least as robust as those ensured under U.S. law.

The final section, Section 10, identifies the agencies responsible for the enforcement of the agricultural export and import limits and the oil and natural gas export prohibition. It specifies schedules of civil and criminal penalties for violations of these limits and prohibitions.

Collectively, the provisions of the Sustainable Trade Act should help ensure that world trade is “free” but also consistently and fairly regulated. Most importantly, they would reduce the scale of trade, helping to achieve a steady state economy in the United States and worldwide. The Sustainable Trade Act promises a global trading network, nudged by U.S. leadership, that decreases the pressure for austerity and extraction—instead promoting distribution of wealth and prosperity—especially in developing countries. This feeder bill of the Steady State Economy Act would bestow modest economic advantages on all nations, without compromising the health of the planet or any one nation’s economy.

David Shreve is a Senior Economist at CASSE.

David Shreve is a Senior Economist at CASSE.

Might want to check your sources.

Your graphic alleging to show the Gini Coefficient (inequality) around the globe certainly is curious.

The legend suggests ‘dark blue’ countries are less unequal than red/orange ones.

I had no idea that Iraq & Pakistan were more economically egalitarian than Uruguay, THE international poster child for socio-economic levelling.

But, hey, what do I know? I only lived there for years.

Thanks for your critical eye, Mike! I’m also surprised by this. Here’s the link to the World Bank blog the map came from: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/inside-the-world-bank-s-new-inequality-indicator–the-number-of-

If you click on Detailed Category under Figure 1, you get an interactive / more detailed version of the same map. It’s worth noting that it “uses the latest Ginis available by country,” which are sometimes quite old–2012 in the case of Iraq (I’ve modified our image caption to reflect this).

I’m no Gini expert, so I (and I’m sure many readers) would benefit if you shared some critiques here on the way Gini is calculated. I’m sure it’s highly imperfect, if anything due to insufficient data.

Thanks for the note, Mike. Even more significant than the “dated” information behind some of these is the notion than a low Gini coefficient can reflect one of two things: 1) low inequality in a prosperous (or relatively prosperous) nation, where broad prosperity is often dependent upon such relative equality; or low income/low prosperity overall, where even the outsized wealth and income of a few oligarchs do not significantly affect the single Gini number. All in all, it’s a useful indicator, but in many places, to get a clearer picture, it generally has to be coupled with other key indicators or economic assessments.

This is too hard to understand. For instance, I don’t understand this:

“They are frequently forced to safeguard domestic purchasing power with high interest rates or fiscal austerity imposed by developed nations at the International Monetary Fund and World Bank Group.”

After this, there are numerous other things that I don’t understand. For instance:

“A fourth of nations engage in international trade with a total (rather than net) value greater than their national income.”

Can this be dumbed down?

Also — does this article assume that the U.S. is part of the *solution* or part of the *problem*?

Peter,

Thanks for pointing out this insufficient clarity. Occasionally, our Steady State Herald goals–for brevity, and for plain language–come into conflict. In this case, the first excerpt speaks to the problem of IMF/World Bank (mostly IMF) pressure to control inflation with measures that kill jobs and economic opportunity in general, in order to “free up” income to repay loans or attract outside investors. If I had written “Frequently, they are forced to fight inflation with job-killing measures,” it would have been clearer but would have also left much more unexplained. Who makes them do this? And with what instruments? There wasn’t enough space to touch on the “why” this happens, and so I likely erred on the side of trying to jam in just a little more context and info.

The second excerpt was a compact way of saying that in some nations the ebb and flow of international trade is so extensive (as in the EU) that if exports and imports are totaled in the aggregate, the monetary value is often greater than the monetary value of their entire economy. This can occur because only the net value (of imports minus exports or vice versa) is counted when figuring up the monetary value of the national economy (rather than the absolute value of both). This was also a compact way of emphasizing the difference between far flung international trading networks (that can often transgress comparative advantage and sustainability) and those conducted between nations sharing borders or close proximity, which are often exercises in decent efficiency. I was guilty, I think, of both trying to cram too much in and also leaving behind too much reading between the lines.

And to your last question (about the U.S. role), while the example of the limited extent of U.S. trade (compared to its purely domestic economic activity) could be misleading, that was introduced to highlight the overarching significance of the purely (or mostly) domestic economic affairs in any nation. Do this well, as we have in the U.S., and trade carries far less significance overall. These two other excerpts, on the other hand, were meant to convey how and why the U.S. must lead in this area:

“The United States must affirm that genuine comparative advantage and global efficiency are the paramount goals. Advantages generated by compromised environmental standards or the suppression of labor rights must be eliminated. U.S. negotiators must leverage trade agreements to marginalize kleptocracies, oligarchies, and the GDP fetishism that still preoccupies many nations.”

and…

“At international forums like the WTO, the United States has an outsized influence on trade agreements and guidance for other countries’ domestic policy. As long as this is the case, the United States must exercise its power to promote the policies necessary for factor-price equalization. A more modest, sustainable, and mutually beneficial international trading system depends upon it.”

In addition, once you reach the descriptions of the bill itself, you’ll see that all of the bill’s key sections focus on policies and factors that the U.S. control, in areas where its leadership is significant.