Radical Post-Growth Gratitude

by Alix Underwood

In our paradoxical society of excess and dissatisfaction, dedicating a day to gratitude is a powerful gesture.

There is abundant evidence of the importance of gratitude for well-being. A dearth of gratitude is a critical component of Western society’s epidemic of dissatisfaction and mental illness.

It’s no coincidence that this epidemic has been accompanied by economic growth beyond planetary boundaries. For degrowth to a steady state economy, we must cultivate a radical kind of post-growth gratitude. In the hands of consumers, such gratitude is a potent weapon that can be wielded at the fuel cap of the GDP bulldozer. On the flip side, the GDP bulldozer could be framed as a weapon of mass gratitude destruction.

I’m grateful for the red maples—native to Maryland, where I live—that greet me with their vibrant fall colors when I take a walk with my dog. (National Parks Gallery, Public Domain)

Post-growth gratitude will look different for each individual, according to their circumstances. For me, at this stage in my steady-state journey, it looks like acknowledging the goodness in everything I consume, material and immaterial. It also entails recognizing the energy, materials, and time that went into the thing I consumed.

If we are to use gratitude for more than self-help—as an agent of social and economic change—we must harness the feeling for action. In my case, if the resources it took to make the things I consume feel overwhelmingly abstract and numerous, I take this as a sign that I’m consuming too much of the wrong things. If gratitude comes naturally—as tends to be the case with quality time spent with loved ones or in nature—I’m consuming the right amount of the right things. I try to make small, sustainable adjustments to my consumption patterns accordingly. It’s a work in progress.

Essential for Satisfaction

Studies link feeling and expressing gratitude to a number of positive outcomes, including increased life satisfaction. One study involved a four-week gratitude contemplation program. Participants consistently reported higher life satisfaction and self-esteem than people in the control group. Another study found that, controlling for demographic and personality traits, a high level of gratitude contributed to psychological well-being and self-esteem. Yet another showed that gratitude reduces envy and increases resilience.

The list of the benefits of gratitude is long. One of them happens to be reduced materialism. A study on marketing students showed that low levels of gratitude were the mediating link between high materialism and low life satisfaction (a well-established relationship).

It’s intuitive: If you’re grateful for what you have, you’re less likely to continually want more.

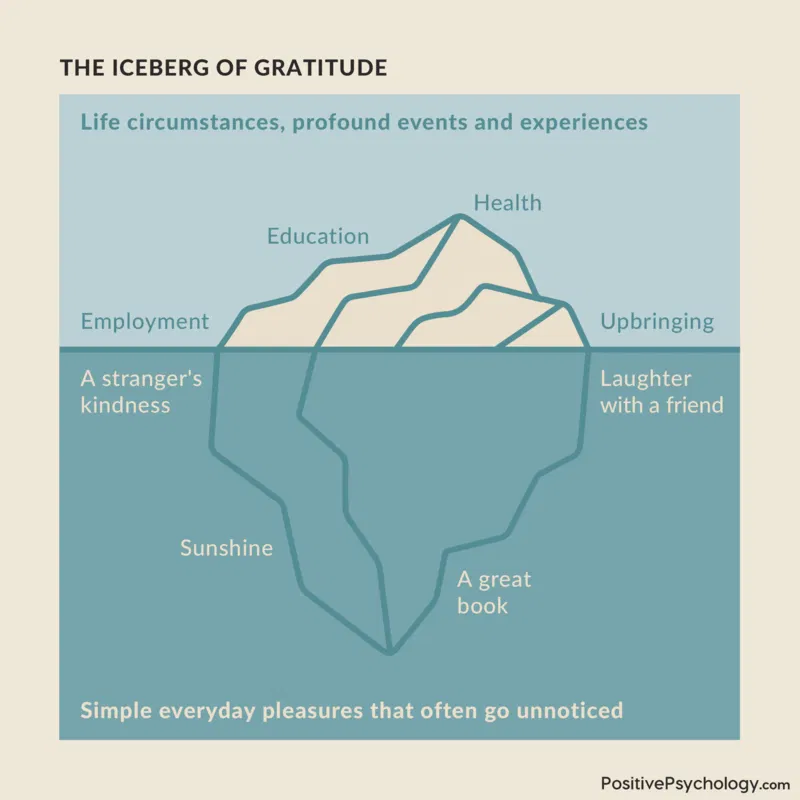

It’s gratitude for the small things, below the surface, that really improves life satisfaction. (Positive Psychology)

But what exactly is gratitude? Psychology professor Robert Emmons frames it as a feeling that involves two stages. Acknowledging goodness in one’s life is the first stage. The second is recognizing that this goodness comes from outside oneself. This recognition that the good things in life are provided by external entities—Earth, for example—makes gratitude the antithesis of entitlement.

There are no rules about which “goods” to be grateful for. However, cultivating gratitude as a long-term trait—as opposed to a transient state—entails extending gratitude to little things. Psychology educator Tiffany Sauber Millacci compares gratitude to an iceberg. Most people, when they take the time for gratitude, think of big-ticket items, such as employment, health, and family. But those are the tip of the iceberg. Adopting a “gratitude attitude” requires going below the surface, acknowledging a breath of fresh air or a shared smile and recognizing it as a blessing.

Extending Millacci’s analogy, the growth economy is putting our gratitude icebergs, like our real icebergs, in peril. (I’m grateful for glaciers and their life-giving role in the water cycle.)

Dissatisfaction and Economic Growth: A Vicious Cycle

Let’s consider three drivers of the positive feedback loop from more consumption to less satisfaction and back again.

1. The More You Have, the Less It Matters

The more stuff you have, the more dispensable it is, and the less you appreciate it. If you and your community have in excess—if you don’t experience shortage—expectation occupies gratitude’s seat in your mind. Instead of feeling grateful for the goods you have, you feel disappointment and resentment about the ones you do not. Your “gratitude muscles” atrophy (assuming you developed them in the first place).

But those muscles are key to life satisfaction, so without them, you feel anxious and insecure. This leaves you vulnerable to comparison and manipulation, ready to buy whatever you’re told will fill the void. So, you’re back at the Amazon checkout, the local Target, or even Saks Fifth Avenue.

2. Market Goods Crowd Out Relational Goods

No material good is a satisfactory substitute for relationships and interactions with nature. (The Resilient Activist, CC0 1.0)

Though the pathway may be more abstract, there is ample evidence that materialism erodes community and a lack of community lends itself to materialism. Materialism stems from “extrinsic” values for financial success and status. These tend to crowd out “intrinsic” values for relationships and community. Your values manifest in the way you spend your time and energy—finite resources. If you value market goods, you spend your time and energy earning money to buy them, then using them until you’re ready to discard them for something new.

In the United States, materialism is a significant predictor of poor relational well-being. This is a two-way street: Valuing possessions as “happiness medicine” or status symbols increases loneliness. Loneliness also increases these materialist values. You’re back at the Amazon checkout.

3. Inequality Breeds Dissatisfaction

As the global economy grows, the wealth accumulation of the richest is accelerating. Billionaire wealth grew three times faster (by $2 trillion) in 2024 than it did in 2023, dwarfing the growth in wealth of the world’s poorest. This trend is particularly evident in the United States.

This doesn’t bode well for gratitude or satisfaction. Social comparison theory posits that one’s relative economic position can have a larger effect than their absolute wealth on their happiness. Evidence supports this theory, with one recent study demonstrating that the “jealousy effect” is stronger than the “proud effect.” In other words, in an unequal context, owning less has a larger negative effect on one’s happiness than the positive effect of owning more. This can be explained by a psychological tendency known as “loss aversion”: People focus more on loss than on gain.

Under certain conditions—carefully cultivated by corporate and investor interests, hereby referred to as the “growth juggernaut”—people at the short end of the inequality stick view their counterparts’ wealth as aspirational, not abominable. Their response is to strive to acquire more wealth and to consume more. The alternative—to lower the wealth ceiling—is a secondary and politically fraught consideration (though most Americans favor raising taxes on the rich).

Back at the Amazon checkout.

The Advertising Assault on Gratitude

Humans are somewhat predisposed to seek material wealth, as a matter of basic biology. And culturally, even before the growth paradigm took hold, plenty of people valued material goods at the expense of relationships, intent on surpassing the wealth of neighbors. But today’s advertising behemoth has charted the ins and outs of this predisposition and harnessed, manipulated, and amplified it.

When people are satisfied with what they have, “manufacturing lack” (not unrelated to “manufacturing consent”) is the GDP bulldozer’s only path forward.

Gratitude, which fuels satisfaction, is growth enemy number one. The growth juggernaut is armed with marketing techniques—informed by cutting-edge psychology—to make you feel anxious and insecure. It has been firing away at consumers’ gratitude since the 1920s, when psychoanalysis was first leveraged for propaganda-style marketing on a large scale.

In the 1920s, Edward Bernays’s infamous tobacco ads idealized thinness, eventually morphing into the “Torches of Freedom” campaign, which linked tobacco to women’s empowerment. (Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

Fear is a primal emotion. There is ample evidence that “fear appeals” influence our attitudes and behaviors. The advertising industry has taken notice. From insurance to health supplements, corporations tap into our survival instincts to convince us to buy their products, and fast! Of course, as social beings, one of our strongest fears is the fear of missing out, the notorious FOMO of social networking fame.

Which leads us to another prominent advertising technique: idealized imagery. Ads that show idealized lifestyles or bodies shift people’s comparison standards, driving consumption to draw closer to the ideal. In academic literature, the well-evidenced link between this type of advertising and insecurity is often framed as an unintended consequence. However, deteriorated self-perception and diminished satisfaction are precisely how idealized imagery gets you to buy stuff. Chief marketing officers in the beauty industry know their ads make young women feel they aren’t enough; that’s the whole idea.

But advertising is only as powerful as its access to you. Enter social media, deftly designed to serve you up on a silver platter to those who seek your attention, your money, and your apathy. 5.42 billion people use social media for an average of almost 2.5 hours per day.

Social media platforms don’t need paid advertising to make users feel anxious and insecure, prone to buying material quick fixes. Even so, social media spending by advertisers is projected to reach $275 billion in 2025 and grow by nine percent each year through 2030. The portion of that spent on influencers, who often seamlessly incorporate ads into their content, is growing much faster: by 36 percent from 2024 to 2025.

Radical Post-Growth Gratitude

We need radical gratitude to defend ourselves against the sophisticated weapons of the growth juggernaut. But gratitude can be more than defense. We can leverage it to put the brakes on the GDP bulldozer.

Post-growth gratitude should not be confused on Thanksgiving (or any other day) with turkey-gobbling abandon. The 46 million turkeys sold in the United States for Thanksgiving are raised in conditions that reflect a complete lack of appreciation for non-human life. The equivalent of eight million of them end up in the trash. That’s just another manifestation of an economy on growth steroids. (Granted, Thanksgiving isn’t the most materialistic U.S. holiday.)

On the contrary, someone wielding post-growth gratitude might acknowledge where every dish on the table came from and what it took to produce it. They would appreciate Earth’s abundance and Earth’s limits. They might feel gratitude for the turkey’s life, ended for their nourishment, and they might strive to give back as much as they take from Earth, with a spirit of reciprocity. They may even decide that the turkey represents a taking they cannot reciprocate and forego it altogether, creating space for new traditions.

Whatever post-growth gratitude looks like for you, how does one foster it? Journaling is prominent among the endless online content on “gratitude exercises”, as are meditation and letter writing. But if you’re searching the web for solutions, be wary, as self-help is a playground for insecurity advertising. (They’re trying to fill a void. Quick; sell them the product!)

A mind full of gratitude, rather than consumer clutter, makes you more comfortable with the backs of your eyelids. (Zeyneb Alishova, Pexels)

For starters, I am wary of anything that encourages me to do or consume more of something without doing or consuming less of something else. This addition-only rhetoric is a product of the growth paradigm, so ubiquitous as to be almost imperceptible. Your mind—the content within it that affects your day-to-day life—is finite. And likely, it’s chock full. Full of that comment someone left on your Facebook post, that disturbing video you saw on Reddit, and that skin-care product that might get your acne under control.

In my non-psychologist opinion, the first step is to clean house. That’s a lot more difficult than it sounds. All that consumer-culture content is designed for you, and you are likely not entirely immune to it. So, you must make intentional, ongoing efforts to expose yourself less—to reclaim control of your brain space.

If you celebrate Thanksgiving by spending it with loved ones (how grateful you must be!), there’s no better time to start. Acknowledge the goodness of the day, starting with the tip of the iceberg, like good health. Then contemplate the iceberg’s underwater mass: a shared smile, a tasty morsel, or a warm hearth. Recognize where these goods came from. Don’t shy away from any accompanying sadness about the exploitative systems that brought you some of these goods (or about the brutal history associated with Thanksgiving). That’s a critical component of post-growth gratitude.

Alix Underwood is managing editor at CASSE.

Alix Underwood is managing editor at CASSE.

Thanks Alix,

I also believe that gratitude is infectious. My Mum (pardon the Australian pronunciation) suffered from polycystic kidneys, had both of them removed when she was 35, eventually had a kidney-transplant, and died at age 62 with the body of an 85-year-old (from years on horrible anti-rejection drugs). She had moments of quite reasonable health, particularly in her 40s, but scarcely went a year between the transplant and her death when she didn’t have at least one short spell in a hospital.

Mum had all the reasons in the world to be bitter (why me?), but she always said there was someone somewhere worse off than her. She was a living angel who, together with Dad, adopted me and my younger sister (in both cases, only weeks after our birth). Her life was all about gratitude – Dad’s was too – and it rubbed off on everyone Mum came into contact with. She was also grateful that she lived in a country with a free and universal health-care system (Americans, you can have one too!).

Gratitude is not just about how appreciation and thankfulness might benefit an individual. It’s also how it can influence others, especially when they can see that you don’t have to be a mass-consumer racing around to tick off and post a photo of yourself on social media doing the next thing on your ‘life bucket list’ to be happy and satisfied.

That’s a nice sentiment Philip and generous of you to share.

I came across a youtube video encouraging gratitude as a life hack.

It goes.. after brushing your teeth in the evening reflect for two minutes on all of the happenings and opportunities of the day that you are grateful for. The idea being that as you repeat this habit you start to notice and become grateful in real time as things happen, noticing opportunities and acting on them.

More and more consumer items is just stuff that is in your way, its the kindness of others and opportunities for us to do better that light up our gratitude sentiment.

The more gratitude I feel for what I have, the more I focus on buying quality items that last. Somehow, the ‘retail therapy’ hawking fast fashion and cheap goods does not lure me in anymore. My quality of life does not increase when I buy more. In fact, consumerism for the sake of it forces me to live amidst clutter, and chains me to… what? Just an awful environment with cheap physical clutter which leads to mental clutter.

Spot on.

All I can add is that as individuals, when we (understandably) seek to improve our lives and immediate physical environment, we’re conditioned to think in terms of *adding* things. But *removing* things can be surprisingly effective in creating a calmer personal space.

In the spirit of this Thanksgiving day, thank you Alix Underwood, for providing both robust research on problems with economic growth and a focus on gratitude for spurring personal transformations and cultural change. That message has often been overlooked in the US where, as Werner Sombart observed in 1906, there is weak support for a labor party or socialism because of the satisfactions of “roast beef and apple pie,” his succulent stand-ins for the appeal of abundance. Or as this essay puts it, the American working class has regarded “wealth as aspirational, not abominable.”

But the heart of this essay is not politics but the feelings beneath it, including with an elegant insight on expectation muffling gratitude with longing for more, especially as advertising has amplified appetite. By contrast, gratitude puts a stopper on the material more by growing satisfactions in more experiences, relationships, sharing in community, small pleasures in nature, health, and laughter, and more mores in the “iceberg of gratitude.” Reduced economic growth is not deprivation, but liberation. Pity those well-heeled enough to own boats or multiple houses. So much stuff to manage. Sufficient material resources are essential; in excess, they become burdens, distracting from other riches.

The crucial role for awakening to gratitude gains reinforcement in the first two Comments, about Philip Lawn’s mother (“Mum”!), “all about gratitude” even with her health problems, and from connor desmond “noticing opportunities and acting on them.” May the good ship Steady State find fuel in the growth of attitudes of gratitude.

Wow, thank you, Philip, Conor, Suzuki, Cole, and Paul, for these thoughtful and personal comments! Researching for and writing this article has made me much more conscientious of all the “goods” in my life this Thanksgiving season. I hope some readers experienced a similar effect. And I hope it didn’t come off as holier than thou… My “post-growth gratitude” needs a lot of cultivation!

Thanks to you, Alix, for your attitude of gratitude! That’s a perspective not holier than thou but thinking with each and every other thou out there.