Rendering the Economic Fat for a Steady State Economy

by Gary Gardner

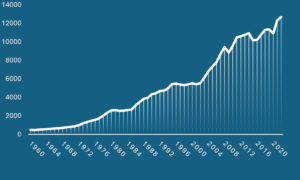

Global GDP per person, 1960-2022, U.S. dollars, inflation adjusted. (World Bank)

Mention the steady state economy at a gathering of friends and a predictable concern is sure to arise. “I couldn’t possibly manage on a flat income, much less a reduced one. I can barely make ends meet now!” Heads will nod all around. The idea of a nongrowing economy—not to mention degrowth—quickly sours the party mood.

The objection is understandable from people long accustomed to ever-greater levels of consumption. But flip the perspective. Given our wealth, humanity has never been better positioned to absorb the transition to smaller economies than it is today. The 20th century was a period of enormous output, creating wealth—and waste—far beyond the material needs for a happy life.

To the objection that we can “barely make ends meet,” I offer a potent data point. Global income per person today is nearly 28 times greater than in 1960—even after stripping out inflation. Many Herald readers, or their parents, were likely making ends meet comfortably in 1960. The challenge today is not insufficient income, but inflated expectations.

Indeed, many wealthy countries are awash in excess and waste. The upside to our cornucopian abundance is that we have ample opportunities to pare down our economies without enormous sacrifice. In fact, many of the opportunities to render the economic fat would likely make us better off.

The greatest pain in our transition to a steady state economy is not likely to come from physical deprivation, but from a shift in psychology. We face the challenge of accepting that many “essentials” of modern life are not essential at all, and may even be encumbrances. Downshifting, individually and societally, could actually be liberating. We may even find that life after excess is the richest life of all.

Tales of Excess

Food Waste

In the summer of 2015, intrepid activist Robin Greenfield biked from Madison, Wisconsin to New York City. An impressive ride, to be sure, but most noteworthy was the fuel he used for his cycling: discarded food from supermarket dumpsters along his route. With the media in tow, Greenfield used his trip to call attention to food waste in the USA by showcasing the completely edible food, often in unopened packages, that he scavenged from garbage bins at every stop.

Greenfield displaying his dumpster bounty in Cleveland. (Robin Greenfield)

Food waste is a tremendous untapped resource for policymakers seeking to build sustainable economies. The U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization reports that nearly one-third of the global harvest goes to waste each year—some on the farm, some in processing and shipment, and some by consumers.

We correctly think of food waste as a moral issue, given the 828 million people globally living in hunger. But its moral shadow has an environmental dimension as well. If a third of food is wasted, then the fertilizer and other inputs that went into that food were wasted, too. And the energy used to make the fertilizer, run the tractors, and deliver the food to market was wasted. Emissions from those activities wasted atmospheric space needed to equilibrate the global temperature. And the farmland that generated the wasted food—and was unavailable for, say, biological conservation—was also wasted.

In other words, reducing food waste would relieve pressure on land, water, energy, and atmospheric resources. Given that agriculture generates 31 percent of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, ending food waste could be a quick-acting strategy for reducing humanity’s climate impact. What’s more, consumers in particular can reduce their generation of waste at little expense, simply by changing purchasing and consumption habits.

Obesity

In the early 1990s, 56 percent of Americans over the age of 20 were overweight or obese. The share surged to more than 72 percent by the 2015–2018 period. Data available for the period since 2018 shows a continued upward trend.

Overweight and obesity contribute to a wide range of health impacts, from diabetes and heart disease to gout and kidney disease. These conditions take a huge financial toll on individuals and institutions. In 2021, people with an obesity or overweight diagnosis averaged $12,588 in health care costs compared to $4,699 for people with no obesity or overweight condition. So addressing the obesity epidemic would yield a huge financial benefit to individuals and society. But it would also contribute to a higher quality of life for the previously afflicted.

Screens

The surgeon general would like a word. (Emily Wade, Unsplash)

Another pool of excessive or imprudent spending is purchases of various screens for kids. The National Institutes of Health reports that 53 percent of U.S. kids have a cell phone by age 11. Yet U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy recently warned that social media is taking a toll on Americans’ mental health, and even called for placing warning labels on social media. Cell phones for kids would seem to offer another win-win opportunity for society. By practicing restraint and telling kids they have to wait, parents can save $822 per child, the average cost of a cell phone in 2023, while protecting kids’ mental health.

Screens on TVs, computers, and video games represent a similar cost-benefit calculus. Pre-teens spend more than four hours per day in front of a screen, and teens more than seven hours. We can explain this exposure partly by kids’ easy access to the technologies. More than 40 percent of children between four and six years old, and more than half of kids eight and older, have a TV or video game console in their bedroom.

The impact is real. Kids with bedroom media consume greater amounts of screen time, which displaces important activities such as reading and sleeping and often leads to poor school performance. Bedroom media also influence risk for obesity and video game addiction and increased their openness to aggression, according to a 2017 study.

Guns

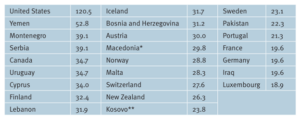

Civilian-held legal and illicit firearms per 100 people in the 25 top-ranked countries and territories, 2017. (Small Arms Survey)

Meanwhile, guns and the carnage they inflict represent an often-overlooked reservoir of spending that could be used to help promote a sustainable society. The USA leads the world in privately owned guns, with more such firearms than it has people, and more than twice as many per capita as the next leading nation, Yemen.

The nation’s stock of guns entails serious costs to society. A 2022 study from the advocacy organization Everytown for Gun Violence finds that gun violence costs $557 billion annually. That’s $1698 for every resident of the USA. This includes not only the immediate medical and investigative costs, but also earnings lost to disability or death, criminal justice costs, and the costs of lost quality of life for victims and their families. And of course no price can be assigned to the lives of the 44,000 people who are killed from guns each year (more than half from suicide).

Significantly, however, these costs are less than half the national average in states with stronger gun laws. The cost in states with weaker gun laws, and where gun injuries and fatalities are higher, is double or more the national average. Thus, gun restrictions offer a simple way to save substantial amounts of money—the $557 billion cost of gun violence is equivalent to 60 percent of the federal government’s non-defense discretionary spending.

Homes

Economies of excess create a need for oversized houses. So it’s little surprise that the square footage of houses in the USA increased 49 percent between 1970 and 2023, even as the average household has shrunk! Yet this increased living space cannot contain all our stuff, so eleven percent of American households now rent storage units. And the country’s stock of more than 50,000 storage facilities is growing: On average, 439 new facilities were added each year from 2010 to 2019, but 735 were added annually between 2020 and 2023. The cost of extra storage to hold excess stuff: $96 per month, on average. This cost arguably belongs on the list of unnecessary expenditures cited above.

A Soft Landing

The set of excesses identified here is a random collection emerging from the briefest of brainstorming efforts. I might also have mentioned the large share of the grain harvest that goes to biofuels and livestock raising. Or tax breaks for the wealthy. Or a bloated defense budget. Herald authors before me have covered other excesses, including NASCAR, fast fashion, planned obsolescence, and luxury goods. Surely readers will have their own examples of excess that could be turned toward building sustainable economies. The cascade of examples suggests a reserve of resources and funds that could help propel the transition to sustainable societies.

Equally important, the examples above suggest that, far from a sacrifice, eliminating excess might leave us better off. Who wouldn’t want to see a society with fewer gun deaths, lower rates of obesity and cardiovascular disease, kids off screens and engaged instead in sports and nature, and lower levels of stuff management?

Happy and healthy, without a screen in sight. (Robert Collins, Unsplash)

The process of paring back might also serve up alternatives that can help create more efficient societies that enhance wellbeing. For example, we might build the sharing economy to better utilize stuff that often sits idle. We have long done this for books by making a shared stock available to all in public libraries. Berkeley, California and Arlington, Virginia extend the library model to include tools. Falls Church, Virginia and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania boast toy libraries. And some towns in Belgium offer items like strollers, car seats, and other baby equipment that are unneeded as a baby grows, but are still very usable. Such creative initiatives provide ways for people to meet particular needs without a large ecological or financial footprint.

Friends who swear they cannot make ends meet might consider an early use of the idiom in Thomas Fuller’s The History of the Worthies of England in about 1661. Fuller wrote, “Worldly wealth he cared not for, desiring only to make both ends meet; and as for that little that lapped over, he gave it to pious uses.”

Taken as our model, the quote suggests that we need to slim down so that resources “lap over,” rather than run short. Then we should tap that surplus for more pious purposes. The archaic language notwithstanding, what could be more pious than sustaining a just economy in balance with nature?

Gary Gardner is Managing Editor at CASSE.

Spot on. As a supporting anecdote, the amount of clutter I see in American households is pretty unreal. Frequently I see yard sales and garage sales where people seek to part with immense piles of useless stuff, and then a couple years later the same house will do it again. In a couple of years they’ve filled their dwelling with cr@p again.

I can’t help but think that the mental health angle of living more in sync with a steady state would be tremendous. Clutter = stress and unhappiness.

Thanks, Cole, and I agree that the mental health angle is important. Living with less can be freeing, and can open up time and space for deeper relationships with others and with nature, all of which can lead to lower stress levels. Who wouldn’t want that? The promise of a less stressful life should sell itself, but we may need to find ways to make that vision as enticing as the (overwrought) promises of a TV ad. Thanks for weighing in…

Yes! Well done. In my first job as a Biology teacher in 1968, my income was $500/month, $6K/year. The next year I made $7200/year, and we thought we were in Fat City! It’s all in one’s viewpoint re what’s really necessary for a contented life, eh?

In 1964, I bought a pair of Levi Strauss blue jeans for $3.95, a common price for quality jeans back then. Over the decades since 1964, prices of everything have risen exponentially; however, unit cost of production has gone down and wages have only kept pace with inflation (in general). It makes one wonder what’s happening. It also seems to show that exponential and infinite economic GROWTH on a finite planet is an oxymoron.

Keep up the good work, Gary.

Much to like in this article, Gary, especially the one about guns! The excess of clutter, especially in huge homes with few or no children where nobody’s home most of the time is nauseating. Just imagine how many homeless people could be served if we emptied all those storage lockers!

But may I quibble a bit?

Inequality has been growing. Those McMansions with the excess clutter belong to the top 1%. I’ve seen charts (not at my fingertips) where the top 0.01% is pulling away from the top 0.1%, which is pulling away from the top 1%, which is leaving 99% in the dust. People legitimately can’t make ends meet because they are house-burdened, debt-burdened (often from college loans), local tax-burdened (which pays for public education), utility-burdened (closing the “digital divide”, courtesy of COVID), and car-burdened (the only way to get to work when they can’t work from home). Wealth and income redistribution is an urgent need.

Agriculture requires dozens of reforms if not hundreds. Large farms in the US grow monocrops of corn and soy, not for food, but for ethanol and oil, the latter for prepared foods and cosmetics. The waste feeds beasts in CAFOs. Before entering the CAFOs, they “ranged free” on burnt-down Amazon rainforest. Industrial ag sucks in one to two orders of magnitude of kilocalories more than the kilocalories it produces, thanks to petrofertilizers, pesticides, mobile equipment, and freshwater-depleting energy-intensive irrigation. While the food waste Robin Greenfield encountered is sad and terrible, it’s a drop in the bucket of necessary ag-land-food reforms that no US government will dare to undertake.

Thanks, Robin. I agree that inequality, a structural problem, is an important factor here, so your comment gets at the question of structurally driven expenditures v. expenditures of personal choice, a distinction I did not address. To be clear, my point was not to blame individuals alone, but an entire system that encourages waste and (often via advertising) frivolous spending. A more nuanced approach would have made this clearer. And yes, reform of agriculture is needed. At the end of the article I gave a nod to the share of the grain harvest that goes to livestock and the share that goes to biofuels, both examples of a poor allocation of resources. Thanks for chiming in!

While I do think there is more than enough for everyone, I don’t think we are going to convince people of that by scolding them about their expenditures or shame them about their eating habits. And even though I followed the link on the expenditures charge I still can’t tell what the source of the statistics was or how they were handled. The source article seemed to mostly be about convincing people they could afford life insurance if they just gave up some “non-essentials”. I would not share this with someone having trouble finding affordable housing within a reasonable commuting distance to their workplace. I think we can do better than this and part of that is being careful not to overstate the contribution of personal consumption on the issue.

(By the by, a large part of the reason for the big jump in obesity is that in 1998 the BMI cutoffs for overweight and obese were lowered. People’s bodies didn’t change, how they were labeled did.)

Thanks, Amy. Regarding scolding, I did not intend to be a finger-wagger, but I can see how it came across that way. I was simply struck by the amount of cushion found in our economy and many examples in daily life came from individuals’ consumption. A broader framing would examine waste in public expenditures, not just personal ones, and would likely have a less-scolding tone. Thanks, also, for identifying the questionable nature of the survey on consumer spending patterns. I have removed that discussion until I can get a better source. Thanks for chiming in!

Expecting individual choices to change to deliver sustainability in the absence of an overall strategy may be overly optimistic. Consumer behaviour is a crowd behaviour, we often operate like the shoals of fish from which we evolved. We’re swimming in capitalist waters and are behaving accordingly, encouraged to consume by the marketing and competing with one another lest we have nothing as it will be competed away from us. Systemic change to cooperate more is the way forward. Encourage social business, support it by purchasing and assisting in any way. Its the switch to a free market non profit non growth economy, an economy driven by cooperation, that can be our saviour. Brand up, wear a Patagonia t shirt and drive that cultural change.