Signs of LIFE: Assessing the European LIFE Programme

by Adel Ramdani

In November 2021, the European Commission approved an investment package of €290 million to support 132 new environmental projects through L’Instrument Financier pour l’Environnement, or the “LIFE” programme. LIFE is designed to help reach the environmental goals outlined in the EU Green Deal, and it’s the only EU funding programme entirely dedicated to environmental, climate, and clean energy objectives. With certain adjustments, it could be more aligned with steady-state principles.

What is the LIFE Programme?

Environmental finance is crucial for fulfilling the goals of the EU Green Deal, including Europe’s goal of becoming climate-neutral by 2050. Fortunately, the EU has a long-standing commitment to financial assistance for environmental protection. In the late 1980s, for example, Europeans shocked by the devastating effects of the Chernobyl catastrophe called for more action on environmental protection. Other issues, including ozone layer deterioration over the poles and climate change, prompted further EU action. Finally, in 1992 the EU adopted an all-encompassing fund for the environment, the aptly named LIFE programme.

From 2014 to 2020, LIFE had a €3.4 billion budget divided into two major sub-programmes, one for environment (comprising 75 percent of the programme) and one for climate action (comprising 25 percent). LIFE’s funding has since increased to €5.4 billion to be spent between 2021 and 2027 for the following areas:

The Chernobyl catastrophe monument and immediate action following the disaster are a testament to the EU’s dedication to environmental protection. (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, Matt Shalvatis)

- Nature and biodiversity

- Circular economy and quality of life

- Climate change mitigation and adaptation

- Clean energy transition

The Nature and Biodiversity sub-programme focuses on the protection and restoration of nature throughout Europe to stop (and to the extent possible reverse) biodiversity loss. It supports projects that help implement the EU Birds and Habitats directives and achieve the objectives of the EU’s biodiversity strategy for 2030, as outlined in the EU Green Deal.

The Circular Economy and Quality of Life sub-programme aims at “facilitating the transition toward a sustainable, circular, toxic-free, energy-efficient, and climate-resilient economy” and “protecting, restoring and improving the quality of the environment, either through direct interventions or by supporting the integration of those objectives in other policies.” Specifically, this sub-programme includes projects aimed at recovering resources from industrial and agricultural waste, as well as recycling materials from discarded and out-of-date goods. Additionally, it establishes environmental governance authorities to execute these programs smoothly and expediently.

The Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation sub-programme administers the shift towards a “sustainable and resilient economy.” For climate change mitigation, LIFE supports projects pertaining to farming, land use, peatland management, renewable energy, and energy efficiency. For adaptation purposes, the sub-programme focuses on urban land-use planning, infrastructure resilience, flood management, and coastal planning in the face of sea-level rise.

Lastly, the Clean Energy Transition sub-programme focuses specifically on the renewable energy transition. The fund goes towards coordination and support efforts, and engages local authorities, nonprofit organizations, and consumers in the clean energy transition.

Given its size, budget, and mandate, LIFE should not be underestimated in its potential to shape a sustainable Europe. LIFE takes a comprehensive and integrated approach to climate change by simultaneously targeting energy, climate change mitigation, and the economy. However, by analyzing specific projects we realize that LIFE fails to bridge the gap between financing environmental initiatives and reforming the economic system that causes environmental deterioration.

Case Study: Fish Conservation in Marine Ecosystems

Overfishing is one of the greatest drivers of declining ocean wildlife populations. The EU’s fishing policy aims to address the problem of catching fish faster than stocks can replenish. The number of overfished stocks has tripled in 50 years, and one-third of assessed fisheries are depleted beyond biological limits. Therefore, the EU has financed several conservation projects to improve the status of fish species “from unfavourable to favourable.” LIFE is financing local partners to eliminate or mitigate major threats, restock rivers, improve habitat quality, and update fishing regulations.

Another key target of LIFE-funded projects is the Mediterranean seafloor, where human activities (like trawling) have dramatically reduced biodiversity. The EU has funded the LIFE ECOREST project, coordinated by the Spanish Institute of Marine Sciences, to restore the natural condition of seafloor habitats off the Catalan coast impacted by fishing activities. Among other measures, the project intends to restore no-take zones (through habitat restoration and fish restocking) over the continental shelf, an action that should “return 75,000 individual organisms into the sea.”

These promising projects are only a few of the more than 5,000 projects already co-financed by LIFE to date. But, with so many projects and money invested in the environment, why don’t we see significant progress towards the expected changes? According to the European Environmental Agency (EEA), Europe will not achieve its 2030 climate and energy targets “without urgent action during the next 10 years.” Meanwhile the agency argues that European biodiversity remains the biggest area of “discouraging progress.”

Limits of LIFE

Many argue that the biggest challenges to fish conservation are outdated fishing regulations and increased international trade. While those factors play a key role in the degradation of marine life, the increasing water pollution and invasive species have been just as damaging. Yet the ultimate factors are the growth of the human population and its consumption: that is, economic growth. Although LIFE addresses some of the consequences of our economic activity on commercial fishing, the program falls short of tackling the root of the problem—the economic system itself.

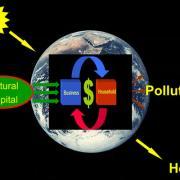

LIFE funds projects believed to advance the EU Green Deal goal of achieving “economic growth decoupled from resource use.” In fact, a significant portion of LIFE and the larger Green Deal is devoted to projects supposedly congruent with a circular, zero-waste economy of “sustainable growth.” But, the second law of thermodynamics, the entropy law, stipulates that a zero-waste economy is impossible, and decoupling growth from resource consumption is likely a hopeless fantasy. So why are we expending more energy and consuming more resources for such a doomed pursuit?

Climate activists beware buzzwords like “decoupling,” “zero-waste,” and “sustainable growth.” (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, Mike Langridge)

If the LIFE programme is to truly make a difference in economic and ecological matters, it must be informed by limits to growth. The issue of aquifer depletion, for instance, is linked with agricultural demand and urban development (including the proliferation of manufacturing and service sectors), meaning protection of marine ecosystems cannot be achieved without addressing the broader economic system.

Limits to growth is not a new debate in Brussels, where many EU institutions are seated. Eric Heymann and Norbert Walter have already explained that it’s “possible to have a higher standard of living—including a clean environment—for everyone, while at the same time consuming less resources and respecting the wellbeing of future generations.” But, reducing consumption won’t happen until policymakers acknowledge the fallacy of endless economic growth and the shortcomings of our debt-based economic system when developing policy.

A key strength of LIFE is indeed its bottom-up approach, solidly grounded in its willingness to finance local and community-driven projects. However, we will not reach the transformational change we require by focusing solely on such initiatives. While these projects are profoundly necessary, we need a bold, systemic change in our economic paradigm to adequately address the climate and ecological crises.

CC BY-NC 2.0, Creator: Stuart Rankin

CC BY-NC 2.0, Creator: Stuart Rankin

Thanks Adel for the informative and insightful article on the EU life program. It is clearly a well intentioned noble endeavour with a multifaceted program. I agree that no matter how comprehensive will it ever be sufficient to offset the ravages of continuous growth. I completely agree that ‘we need a bold, systemic change in our economic paradigm’ – a change that will also address the wealth gap to improve the social and economic imbalance – so that personal potential has every opportunity to flourish,. Necessity is the mother of invention. Effort needs to be focused on finding this new best direction. Hopefully change comes soon.