Unlearning Growth: Reclaiming Higher Education for Sustainability

by Zachary Czuprynski

What it means to “increase and grow” has shifted at many universities (Picryl).

At the bottom of McGill University’s coat of arms, beneath the red shield, a scroll reads Grandescunt Aucta Labore— “By work, all things increase and grow.” Historically, mottos of higher education institutions (HEIs) symbolize the cultivation of virtues and moral excellence, often rooted in religion. Over time, however, this idea of growth in personal and moral development became tainted by the paradigm of economic growth.

Today, HEIs are celebrated for their role in advancing economic growth by generating scientific knowledge, supplying skilled labor, and driving productivity. Millions of graduates depart HEIs every year to fuel industries and “increase and grow” the economy. Yet the growth paradigm mistakenly conflates societal wellbeing with continuous economic expansion. It has left us instead with social, ecological, and economic crises.

Let’s trace the pivotal historical moments that entrenched HEIs with the growth paradigm. Then, let’s imagine pathways for reorienting their role toward sustainability and equity in a post-growth world. What could higher education look like if it resisted the growth imperative and aligned itself with the needs of the planet and society instead?

Industrialization: Knowledge in Service of Expansion

Early HEIs were tied to religious and philosophical traditions. Knowledge was valued for understanding the divine and contemplating human purpose. This reflected a worldview in which “growth” was primarily spiritual or intellectual. The Industrial Revolution changed this status quo as systematic experimentation and technological innovation made its way into academia.

HEIs pivoted their focus from clerical and classical studies to those deemed more “practical”—the sciences, mathematics, and engineering. Colleges like Harvard, Yale, and UPenn installed technical programs to support American capitalism. This realignment met the demands of burgeoning industries that required specific skilled labor and technical expertise.

Iowa State University’s Morrill Hall (Joe Wolf, Flickr). Many land-grant universities have a Morrill Hall.

As industrialization intensified, HEIs further aligned themselves with industry priorities. Governments viewed universities as fertile sites for producing expertise. The United States’ Morrill Land-Grant Acts of 1862 and 1890 institutionalized this trend by funding new technical and agricultural schools, often on expropriated Indigenous lands. Institutions like Texas A&M and MIT provided practical training in agriculture, engineering, and applied sciences. Each state tailored its HEIs to support dominant local industries, from dairy in Wisconsin to mining in Colorado.

Land-grant colleges improved many people’s quality of life. They made education widely accessible to workers seeking employable skills and secure, comfortable lives for their families. “Higher learning” was increasingly sidelined for skill development and pre-job training—a transformation still apparent today as students opt for “practical” degrees. Golding & Katz summarize the shift: “Science replaced art in production; the professional replaced the tinkerer as producer.” Although this realignment offers tangible benefits for many, the promise of a “better life” comes at the expense of a broader purpose for education.

War and Knowledge: Universities as National Assets

HEIs were crucial to the Manhattan Project, contributing scientists, equipment, and research (Los Alamos National Laboratory, Wikimedia Commons).

The world wars further entrenched HEIs in service to economic and industrial growth, this time under the narrative of national development and security. During World War II, universities were central to innovations such as radar, jet propulsion, and nuclear weaponry. These efforts not only influenced the outcomes of the conflicts but also established a framework for long-term partnerships between academia, governments, and industry.

After the war, this collaboration deepened with the establishment of agencies like the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health. These agencies conducted and funded research aligned with national priorities. The Cold War added a new layer to this dynamic: Gross domestic product (GDP) emerged as the dominant measure of national success, linking economic growth with prosperity. This elevated universities as sites for producing intellectual capital, whether through cutting-edge research, technological advancements, or ideologically driven knowledge dissemination.

As economic growth became a metric of national strength, HEIs increasingly oriented research efforts toward industrial and governmental objectives. This legacy is still present in funding structures that support national interests and economic competitiveness rather than solutions to the polycrisis.

The Neoliberal Turn and the Rise of Entrepreneurial Universities

The neoliberal policies of the late 20th century marked the transition of HEIs from public institutions to market-driven entities. HEIs began prioritizing efficiency, financial growth, and competition. Public funding cuts during the Reagan and Thatcher administrations forced universities to seek alternative revenue sources. Today, many schools rely on exorbitant tuition rates and an exploitative adjunct model for a “financially feasible” model that covers operational costs. As a result, students face heavier financial burdens. Meanwhile, adjunct faculty bear cost-cutting measures through underpaid and precarious employment.

Universities worldwide compete for rankings and celebrate when they’ve made it onto a top-50 list (Petaling Jaya, Free Malaysia Today).

Global ranking systems, such as the Times Higher Education and QS World University Rankings, reinforce competitive dynamics. They drive institutions to chase measurable and marketable achievements linked to research output, citations, and reputation. Universities focus on increasing student enrollments, recruiting faculty with high citation counts, and procuring lucrative research grants. These dynamics create a self-reinforcing loop, where growth and prestige are both the means and the end in the neoliberal paradigm.

The neoliberal turn commodified higher education and reframed it as an individual investment in economic success rather than a public good fostering civic responsibility or even critical thought. “Education in the university moved from developing educated, critically thinking citizens to shaping students into competitive, self-interested, and self-reliant individuals for whom the greatest goods are freedom and consumption.”

Reimagining HEIs for a Post-Growth World

As universities strive to keep up with the growth imperative, they reinforce systems that prioritize growth over sustainability. Yet could HEIs become catalysts for a post-growth transformation? What changes are needed to align education with planetary boundaries and social needs?

For What Purpose?

Experiential and place-based learning are essential in a post-growth education (Speak for the Trees Boston).

To challenge the growth paradigm, higher-education leaders must shift from asking What does the economy demand from education? to What do people and planet demand from education? This requires restoring universities as spaces cultivating curious, engaged citizens who are empowered to tackle wicked problems. This could involve integrating inter- and transdisciplinary courses that address complex global challenges, such as climate change, inequality, and technological ethics; requiring experiential programs that emphasize community service and social responsibility; and leveraging place-based approaches that foster participatory stewardship of local environments.

Research also highlights a need for a decolonized education. This refers to education that provides an accurate assessment of how the economic system works, critiques that system, and trains students to imagine alternative, post-growth visions.

Several HEIs are already leading with alternative education models. Prescott College is a small school in the southwest United States that emphasizes place-based, experiential learning in regenerative practices. College of the Atlantic specializes in a single degree—Human Ecology—exploring the interconnections between humans and their local environments. The Autonomous University of Barcelona offers the first two graduate degrees in degrowth. McGill University and the University of Vermont collaborate on a program called Leadership for the Ecozoic. This program trains early-stage researchers to advance transdisciplinary scholarship for a better future. Many other programs exist and are slowly building a network of post-growth education.

Divestment and Beyond

In recent years, we’ve witnessed massive on-campus protests around movements like Black Lives Matter, fossil fuel divestment, and defunding the Military-Industrial Complex. Many of these movements have been successful. Consider the recent actions by Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, where students and employees conducted a 40-hour reading marathon of the IPCC report. This catalyzed VU and several other universities in the Netherlands to cut ties with the fossil fuel industry. In addition to divesting, they halted research that advances socially and environmentally harmful industries.

Students are a powerful force in mobilizing change at HEIs (James Ennis, Wikimedia Commons).

HEIs must go further, forming partnerships that prioritize ecological and social goals. Sustainable procurement practices, ethical investment portfolios, and community-centered research initiatives can all contribute to this transformation.

A Greater Good

Transforming the corporate university model requires reinstating education as a public good—a resource that benefits all of society. One approach is to eliminate tuition, as Nordic countries have. This would redefine education as a publicly funded priority rather than a market-based commodity. This shift would require rethinking funding mechanisms and most likely rely on significant public investment.

Reallocating subsidies from harmful industries is one possible mechanism to support this initiative. Another is a wealth tax or other forms of progressive taxation. For example, as a rider to CASSE’s Salary Cap Act, a portion of self-employed earnings over the cap could be allocated to education. Alternatively, institutions could explore cooperative funding models like income-share agreements or community-based financing. These models offer more equitable ways to support students without burdening them with debt.

Metrics that Matter

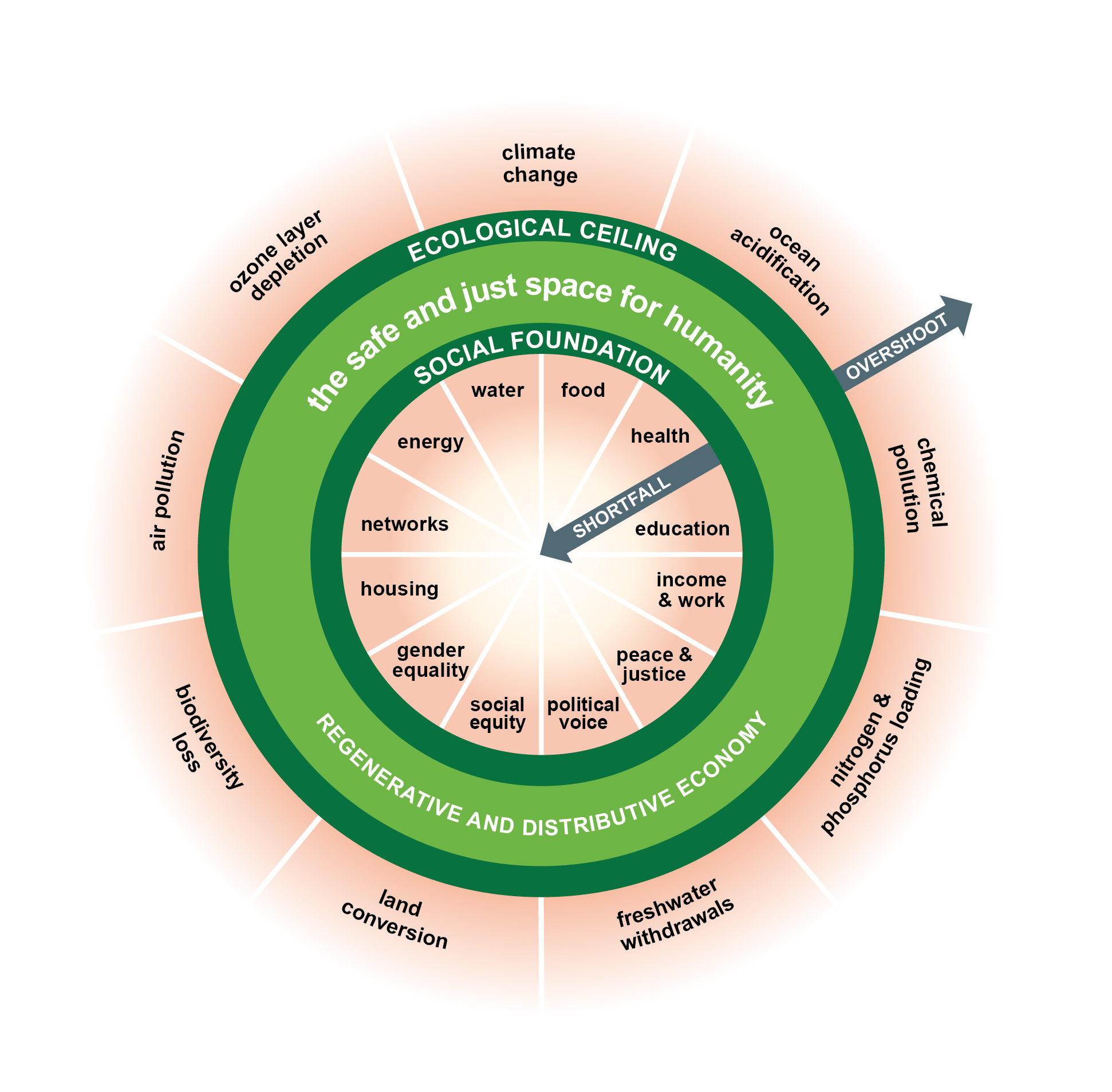

Current metrics of college and university success incentivize competition and prestige, perpetuating the growth paradigm. HEIs can adopt alternative metrics that reflect biophysical, socio-economic, and academic well-being, encompassing a more holistic framework of success in a post-growth world.

- Biophysical Indicators – Colleges and universities have an associated throughput with their operations, just like cities and nations. HEIs could track their greenhouse gas emissions, energy and water consumption, pesticide use, and air pollution. They could also measure potential ‘sinks’ such as tree canopy ratio, restoration efforts, and on-campus composting operations.

- Socio-economic Indicators – These metrics could include information on employee wages, gender parity, cultural inclusion, student debt, campus food security, and connectivity to essential services.

- Academic Culture Indicators – HEIs could track post-growth values or sustainability attitudes on campus, overtime worked by employees, crime prevalence, overall job satisfaction, completion time by students, voice and power in decision-making, and general institutional concern for environmental and social crises.

The doughnut of ecological overshoot and social shortfalls can be adapted to HEIs (Doughnut Economics, Wikimedia Commons).

Several HEIs are already tracking these metrics, either for reporting requirements or through voluntary reporting systems like AASHE STARS. These data could map to a “doughnut diagram,” to see which indicators are in overshoot and which are in shortfall. For example, the University of Lausanne in Switzerland adopted the doughnut in 2022 to track improvements in the campus’s biophysical footprint and social impact. This visual approach to measuring success may inspire HEI betterment rather than intercampus competition.

The Future of Education: Growth or Beyond?

Higher education has always responded to broad cultural and societal transformations, from Enlightenment ideals to the demands of industrialization, wartime innovation, and marketization. Today it faces a choice: Continue perpetuating the growth paradigm or reimagine higher education as a force for transformation into a post-growth, steady-state world.

HEIs have the potential to catalyze such a transformation by redefining their purpose, breaking partnerships with harmful industries, adopting new metrics of success, and restoring education as a public good. By embracing these changes, universities can help build a world that values planetary health and social well-being over profit and prestige.

Zachary Czuprynski is Sustainability Coordinator of Prescott College.

Zachary Czuprynski is Sustainability Coordinator of Prescott College.

15 years ago my daughter considered Prescott College because the boys there were outdoorsy hunks.

Seriously, most HEIs these days are endowment machines. They aren’t even interested in the economy. They are just interested in how much endowment their prestige can generate. Well, things will change as AI takes over education, though probably not for the better.