The World Fertility Transition: Moving Toward a Steady-State Population

by Max Kummerow

“There’s just too many of us and no one is talking about it.”

—Biologist Patrick Benson in Meera Subramanian’s, A River Runs Again: India’s Natural World in Crisis

It is hard to imagine a growing population supporting a steady state economy. “Jobs” and higher incomes for growing numbers of people anchor the platforms of political candidates and economists worldwide.

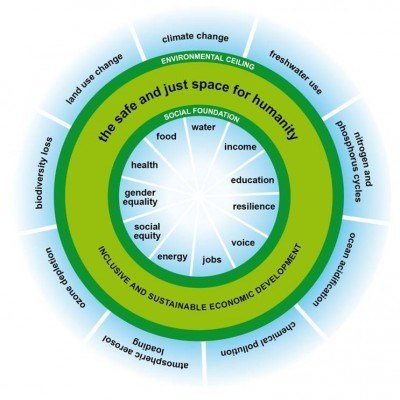

But what about a different approach? Why not reduce population to a size that fits the planet, allowing sustainable economies and decent standards of living?

An illustration of the “negative externalities of overpopulation”. (Left: public domain. Right: Image by James Cridland, CC BY 2.0)

It is possible, because we have seen that educated, liberated women usually choose small families, and population decline has already begun in a few countries. Could the world reduce population to make fewer demands on the planet and allow an economy of abundance? The following summarizes the current status of efforts to reverse an unhealthy rate of population growth and points to a need for establishing a sustainable population size.

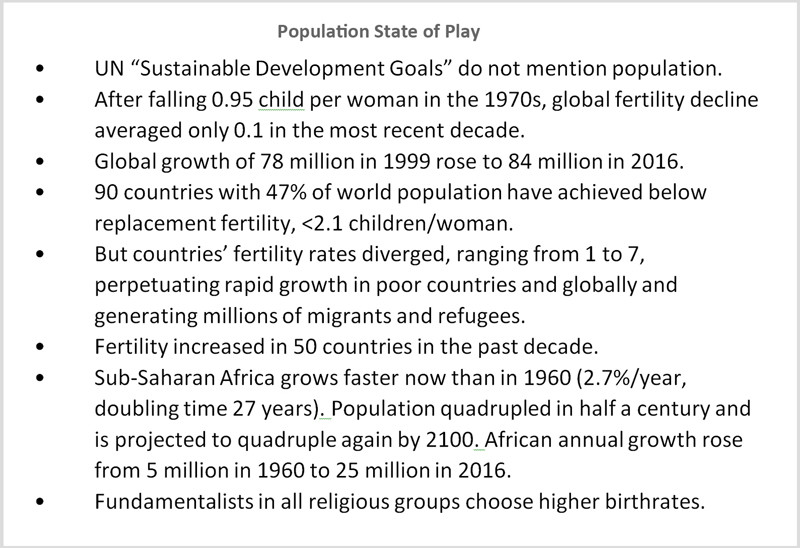

Global average fertility rates fell from 5 to 2.4 children per woman from 1970 to 2010. Population growth rates halved too, from 2% to 1.1% per year.* Contraceptive technology keeps improving. But fertility rates were not reduced enough to offset the rate of population growth. Today, growth continues as fast as ever, increasing by 80 million people per year—a billion more of us every 12 years. Here’s the math:

2% population growth rate times 3.5 billion people in 1970 = 1% population growth rate times 7 billion people in 2010

Long-term stabilized population will require active fertility transitions in more than 100 countries. Fertility transitions are achievable, but they are contingent on deliberate choices and actions by governments and individuals. Fertility transitions around the world won’t happen fast enough without improved access to contraceptives, education for both men and women, and efforts to change cultural fertility norms to accept smaller families and deliberate choices to lower fertility rate.

Like the Titanic headed toward an iceberg, it takes a long time to reverse population growth or even slow it down. In countries with the highest fertility rates, half the population is less than 15 years old, and it takes approximately 50 years for “population momentum” to slow, as those children grow up and are then able to make choices about the number of children they will have. For example, even though Japan’s fertility rate fell below replacement (2.1) in 1957, its population kept growing until 2008. China had 900 million people when the One-Child policy began in 1979, but it will peak near 1.3 billion around the year 2030.

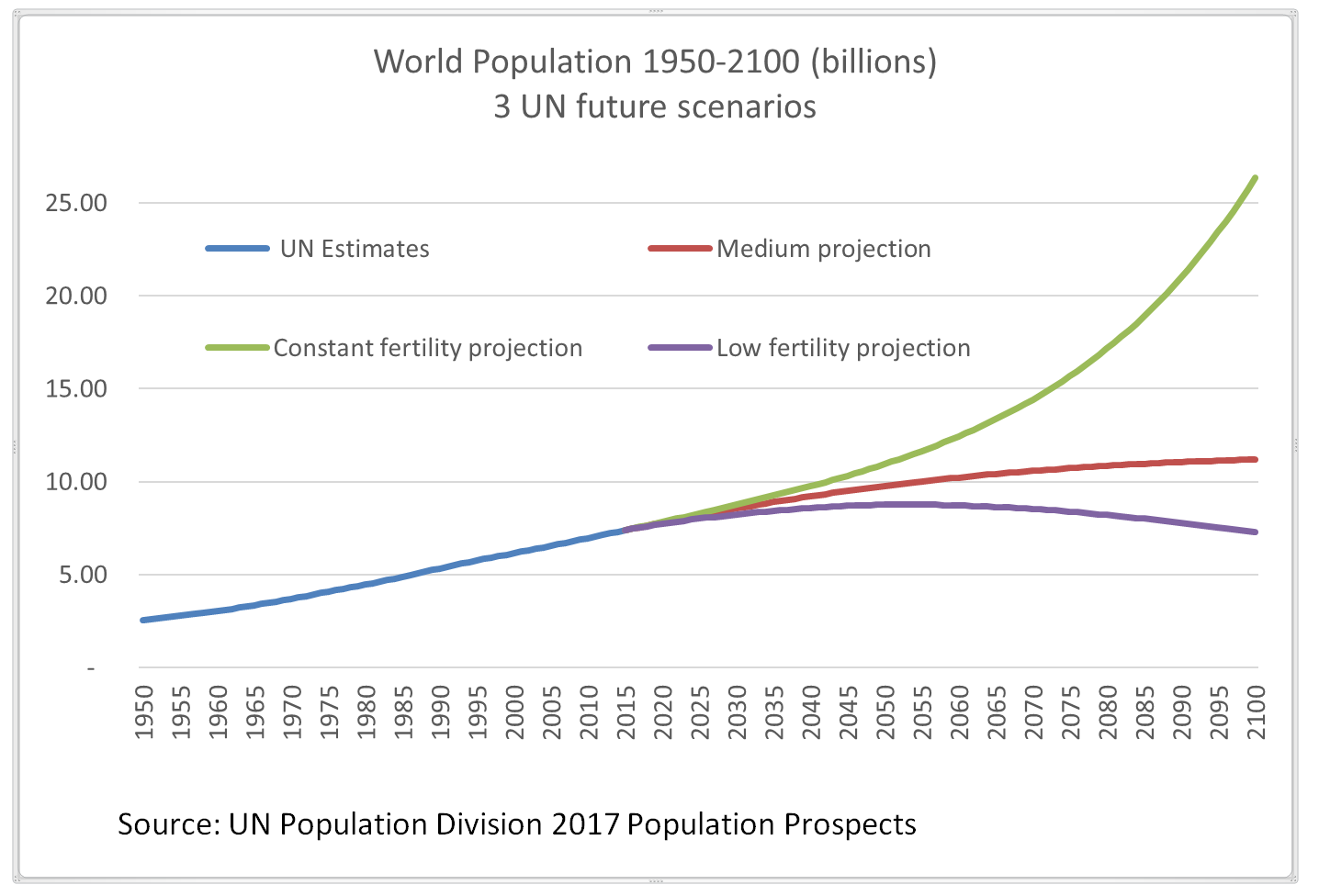

A graph of possible future scenarios using data from the United Nations shows world population quadrupling from 2.5 to 10 billion in a the century from 1950 to 2050. The three UN scenarios—low fertility, medium fertility, and continuation of current fertility—give outcomes that range from 7 to 26 billion by the year 2100. The difference is due to a wide range of possible outcomes, future policies, and individual choices.

UN global 2050 projections were revised upward by 900 million between 2002 and 2017 (from 8.9 to 9.8 billion) as fertility decline stalled. Sub-Saharan Africa still averages approximately 5 births per woman, as high as 1970 rates. Worldwide, about 200 million women who do not want to get pregnant have “unmet need” for modern contraceptives. Nearly half of all pregnancies worldwide are unintended, whether due to lack of contraception or lack of education for men and women.

Much is known about how to achieve lower fertility rates from demographic research and the experience of diverse countries—Iran, Brazil, Thailand and many others. Low fertility helped families and countries find prosperity through a “demographic dividend” in which the working-age population is larger than non-working-age groups. Government family-planning campaigns and policies aided successful transitions, especially in the East Asian “Tiger” economies that went from poverty to prosperity in a single generation as birth rates fell and stabilized at more sustainable numbers.

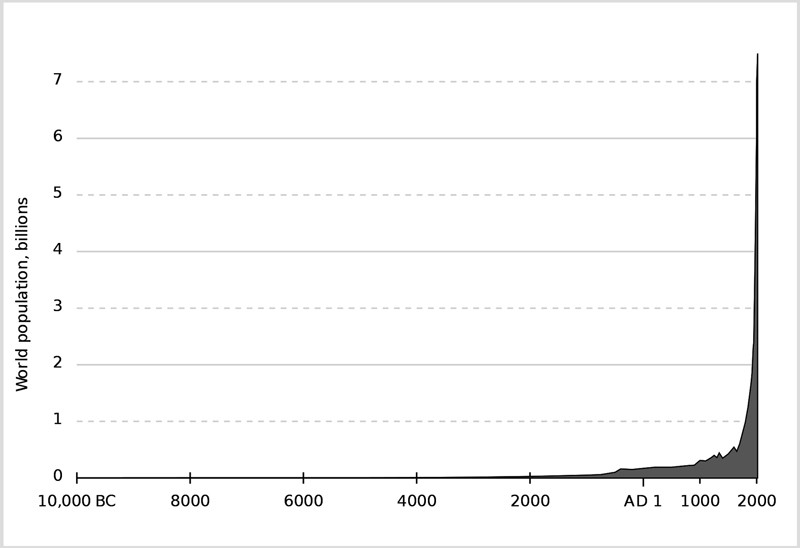

Graph showing an unsustainable “hockey stick” explosion of human population in the past few centuries.

A population too large for the planet has a heavy carbon footprint too. Americans emit far more carbon per person than underdeveloped countries. In China, reducing fertility rates increased environmental impacts by spurring economic growth, highlighting the interplay among population, consumption, technology, and social justice. Every person born becomes a consumer in need of resources like food and water, and many are born into cultures that fuel advertising-stoked desires to consume more.

Population stability is therefore a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition for a steady state economy. A world in which rising population leads the world toward poverty, war, and shortages of all kinds of resources is Malthusian and certainly not ideal. But, with declining population, a steady state economy with a sustainable level of prosperity becomes realistic and feasible, given a green, recovering planet.

People around the world should be talking a lot more about the world fertility transition and working on ways to create change—and a desire for sustainable global, national, and local populations.

* All statistics in this piece are from the United Nations and World Bank.

Max Kummerow is a retired business school professor and population activist who researches demography, ecology, and economic development. He has presented papers at ESA, PJSA, NCSE, PAA and EAERE meetings showing the benefits of accelerating the world’s stalled demographic transition toward lower fertility rates.

Max Kummerow is a retired business school professor and population activist who researches demography, ecology, and economic development. He has presented papers at ESA, PJSA, NCSE, PAA and EAERE meetings showing the benefits of accelerating the world’s stalled demographic transition toward lower fertility rates.

Thank you for this! I can only add three additional thoughts:

1) At the level of national policymakers, there’s a lot of inertia and centuries-old thinking that equates bigger populations with more power. Specifically elites like the idea of having (to be blunt) bigger armies. This is not only disturbing as a motive, it’s also no longer true. Hordes no longer equate to national power, for what it’s worth.

2) Happily I think people around the world are concluding that when it comes to children, quality matters now more than quantity. Humans are becoming more and more of a “K selected species” (https://www.britannica.com/science/K-selected-species) where parents devote more resources and time to raising each individual child. Which is good.

3) Regarding a larger percentage of populations becoming older: this gets a lot of handwringing in many circles, but it shouldn’t. If our civilization was based on manual labor, sure, it would better to have younger backs for doing all the back-breaking work. But happily that’s not the case. I’ll predict that the most successful societies going forward will be those that tap the consulting wisdom and experience of their burgeoning senior population. Instead of viewing the currently retired population as worn-out bodies, we’d do well to view them as savvy advisors who should be paid well for part time consulting.