A Steady-State Approach to Immigration

by Brian Czech

“Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses…” The USA has been a nation of immigration. (CC BY-SA 4.0, Mcj1800)

Steady staters live with the reality that economic growth is unsustainable. It can continue for only so long before Nature will no longer support it. Therefore, we call for stabilization—the steady state economy—rather than growth. In particular, population and per capita consumption must be stabilized. Of the two, population is the most fundamental aspect of stabilizing the economy and its ecological footprint.

The population of a country is determined by births, deaths, immigration, and emigration. The focus here is on immigration. Why? Because in North America, western Europe, Australia and a few other regions, most of the population growth in the past few decades has come from immigration, not the “native” growth rate. Furthermore, in these regions the role of immigration in population growth has increased rapidly. Immigration has become a driving concern for citizens, especially conservatives.

There’s another reason to focus on immigration, at least in this venue. Steady staters have something special to offer; namely, a policy framework that makes eminent ecological, economic, and political sense. It just might be the political elixir needed to satisfy the divergent needs of all (or most) involved in the immigration debates.

The Meaning of “Native”

We should never forget who the real natives are. In the USA and much of the Western Hemisphere, Native Americans came first. They and their tribal cultures were largely eliminated by the growth of nations populated by European immigrants. From the perspective of Native Americans, perhaps “invaders” is a better label than “immigrants” for the European colonizers of the second millennium.

The real natives. (CC BY-SA 3.0, Turn685)

A similar acknowledgement pertains to Aborigines in Australia, Maori in New Zealand, Uyghurs in China, Buryats in Russia, and Saami in northern Europe. Standard practice is to refer to the great diversity of such groups with the capitalized “Indigenous peoples,” emphasizing their equality with “Europeans,” “Americans,” “Asians,” and other geocentric groups and their diaspora. Indigenous peoples are the original, bona fide natives.

That said, “native” is also a handy term for the resident citizens of countries today, in contrast with non-citizen occupants, the vast majority of which are immigrants. “Native” can be used as a noun or an adjective: for example, “Chinese natives” (Chinese citizens living in China) and “native French” (French citizens living in France). Heretofore, I use “native” in this demographic/political sense. U.S. natives, then, are American citizens (including Native Americans) living in the USA.

The final proviso is that “native” also implies place of birth. For example, a Polish immigrant attaining citizenship in the USA wouldn’t be considered a U.S. native. However, his or her children, if born in the USA, would be.

Native Birth Rates

Writers tend to use the terms “birth rate” and “fertility rate” interchangeably, while demographic authorities attempt to distinguish the two, as well as versions of each. Here we’ll consider both terms in a manner that should be self-explanatory.

Happy family of two parents and two children. (CC0 1.0, Mircea Iancu)

The birth rate of U.S. natives is down to 1.6 births per woman. That’s significantly lower than the steady-state rate of 2.1 (aka “replacement rate”). The USA is among 65 countries and territories in which birth rates are below replacement rates. South Korea has the lowest birth rate at 0.9.

All European countries have birth rates below the replacement rate. Many of them, especially in Eastern Europe, have birth rates below 1.5.

Meanwhile, numerous countries have birth rates far higher than the replacement rate. African countries have the highest birth rates, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, followed by southwestern Asian countries including Iraq, Tajikistan, and Pakistan.

We can leave it to The Economist and the Institute for Family Studies to argue about whether or not birth rates are too high for the particular times and places of various African countries. The upshot here is that, with all the aforementioned low rates and high rates accounted for, the global birth rate is 2.4. That’s less than half of what it was in 1960, and it’s still declining toward the global replacement rate, which is estimated at 2.3.

Few disagree that a demographic transition has transpired in many countries, lowering fertility to replacement rates (or lower). The verdict is not so clear on whether the demographic transition model will apply to the high-birth countries of Africa and southwest Asia. The global birth rate hangs in the balance.

Population Growth and Immigration in Wealthy Regions

The U.S. population grew at its slowest rate ever—0.1 percent—from 2020-2021. Native births minus deaths, or “natural increase,” was down to 148,000, while “net international migration” (immigration minus emigration) was also relatively low at 247,000. Both of these figures reflect the effects of the COVID pandemic. However, they also reflect a more durable trend, with or without COVID: Immigration—not natural increase—has become the primary cause of U.S. population growth.

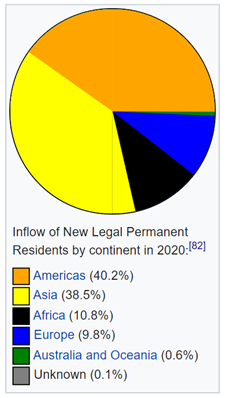

(DHS)

For many years, the USA has taken in by far the largest number of immigrants. From 1965–2015 the U.S. population grew by 131 million (68 percent), including 72 million “linked to immigration” (that is, immigrants per se plus the children and grandchildren thereof). In 2016 alone, U.S. net migration was over a million. Today, over 40 million people in the USA were born in another country, “accounting for about one-fifth of the world’s migrants.”

Germany, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and the UK round out the top five countries for receiving immigrants. France, Canada, and Australia are also in the top ten.

The country producing by far the most emigrants is India, followed by Mexico, Russia (a country of frequent migration in both directions), China, and Syria. Pakistan, Ukraine, and the Philippines are also in the top ten. U.S. immigrants come primarily from Mexico, China, India, the Philippines, and El Salvador.

Immigration Politics

Why wouldn’t immigration be one of the hottest political issues of our time, or of any time? We need only recall the Lasswellian definition of politics—who gets what, when, how—to realize that immigration is like a flame under the political stove or a bee in the political bonnet. It’s up there with taxes, inflation, and health care. In fact, it’s hotter than each of those because it’s all about the very first political variable: the who in the “who gets what.” Who gets health care, who gets schooling, who gets job opportunities?

Yes, slick politicians with their neoclassical economists in tow will tell you we can all get more and better health care, schooling, and jobs. We and immigrants alike. In fact, we need more immigrants for more entrepreneurial spirit, cheaper labor, and higher demand for the existing products. And remember, “a rising tide lifts all boats.”

The beauty of diversity. Unfortunately, not all faces are smiling as limits to growth are reached. (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, Julie Kertesz)

The neoclassical firmament is cracking, though, as pro-growth, conservative politicians have turned against immigration. They may not know it yet, but they’ve bumped up against limits to growth. Immigration is teaching them a lesson, if only they’ll study it.

Immigration is no faceless issue like firearms or fentanyl, either. Immigration is all about faces. It’s about racial, religious, and ethnic diversity, where diversity is synonymous with dissimilarity or difference. That’s what makes immigration inherently challenging, politically, for practically everyone. Rapid diversification can quickly descend into an “us vs. them” mentality unless civility is cultivated and nurtured by all parties.

The USA, Statue of Liberty and all, hasn’t fared well with the challenge. While it has a constitutional government and a bill of rights, it also has a history of racial injustice and ethnic discrimination. The history is still being written, too. In fact, the USA today is viewed worldwide as a country of racial and ethnic discrimination.

Yet the notion that the USA—or any country—should simply open the doors to anyone and everyone is clearly unsustainable, impractical, and unwise. Therefore, centric politicians like Joe Biden and most Democrats opt for nuanced policy frameworks intended to balance the needs of U.S. citizens with a moral approach to international affairs.

In addition to moral nuance, Biden and the Dems find it handy that an army of neoclassical economists will back them up on purely material terms as well, touting immigration as the cure to a flagging rate of GDP growth. “Research suggests,” we find at JoeBiden.com, “that ‘the total annual contribution of foreign-born workers is roughly $2 trillion’,” with the Biden campaign quoting economists from the Hamilton Project, whose motto is “Advancing Opportunity, Prosperity, and Growth.”

The Steady-State Solution to the Immigration Challenge

For steady staters, there’s no way around it: Population stabilization is as fundamental to a steady state economy as a horse is to a horse race. Yet population stabilization can’t come at the expense of civil rights or impoverished masses, either. Not morally, and not politically.

Given these conditions, the only feasible solution to the immigration challenge comes into focus. The steady-state nation must tighten its borders to the degree that population is stabilized, but only while transitioning to a steady state economy. At the same time, it must lend a helping hand to impoverished regions, essentially in lieu of welcoming the emigrants thereof. In many cases, the helping hand would amount to a better deal for the impoverished, too, for how many among them would really want to leave their homeland, if only conditions were better there?

In contrast, consider what would happen if a big, wealthy country tightened its borders while striving for GDP growth. Recall that all wealthy countries at this point in history have stable, stabilizing, or even declining native populations. For them, tightened borders with a growing GDP would amount to a growing per capita consumption, even while their ecological footprints are already far into overshoot. Locking out impoverished emigrants would make them look like—and be like—pigs at the global trough, especially as wealthy nations lean heavily upon poorer countries for natural resources.

If you’re a pig at the global trough, how good can that be for national security?

Put yourself in her submerged shoes. Should wealthy countries not help? (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, Oxfam International)

Unfortunately, we already have an idea, because with Donald Trump as president, the USA did tighten its borders substantially, even before the COVID pandemic. Trump’s draconian immigration policies were significant factors in the plummeting global approval of the USA during his presidency. Trump’s handling of immigration became a how-to manual for marching toward pariah status in international affairs.

Now let’s try a thought experiment. Let’s say the president was more like a Jimmy Carter, with a Congress wise enough to pass the Full and Sustainable Employment Act (aka Full Seas Act) calling for the transition to a steady state economy in the USA and steady statesmanship in international diplomacy. I chose Carter for this experiment because of his well-known conservation ethic and his honest, humble demeanor. Those traits seem like a natural fit for steady-state economics, domestically and in international affairs.

Imagine this 21st century “President Carter” announcing to the world—perhaps at the UN General Assembly, a G7 meeting, or a climate summit—that the USA, recognizing limits to growth, was determined to establish a steady state economy with stabilized population and GDP. Imagine him (or her) apprising the international community, “We have to. It’s the smart thing to do, it’s the only sustainable option, and now, with the Full Seas Act, it’s the law.”

Next, the president would acknowledge how this transition would affect our friends around the world. “Establishing a steady state economy means we don’t have any choice but to keep our immigration numbers at a level congruent with a non-growing, stable population. We realize, too, that emigrants in many cases are attempting to leave impoverished regions for a better life, and we want to help them. Our help, though, must be less in the form of an open border, and more in the form of improving conditions in the homelands of all who suffer from low standards of living and limited opportunities.”

The Full Seas Act would indeed authorize an Aid-In-Place Fund with mandatory minimum appropriations calculated to assist, at a reasonable level, the same number of people that otherwise would have legally emigrated to the USA (based upon a reference period). This aid, administered by the U.S. Agency for International Development, would take the form of housing, health care, schooling, job training, and other living standards on a case-by-case basis. In other words, aid packages would be tailored to the specific challenges of the region in question. In cases of natural disaster and ecological deterioration due to global heating, such as sea-level rise, the Aid-In-Place Fund would assist (in concert with the U.S. Foreign Service) with relocation to ecologically and culturally similar regions.

Given a 21st century President Carter, the Full Seas Act, and the Aid-In-Place Fund, imagine how the people of the world would view the USA. Not like a pig at a trough, but more like a mature, stable, helping friend. A friend to the world, leading the way with a sane, sustainable immigration policy.

Brian Czech is CASSE’s Executive Director.

Brian Czech is CASSE’s Executive Director.

“We need cheaper labor” is where I stopped reading.

Looks like you misquoted me, plus pulled your misquote out of context. You’re referring to a paragraph where I was exposing the fallacious beliefs of neoclassical economists:

“Yes, slick politicians with their neoclassical economists in tow will tell you we can all get more and better health care, schooling, and jobs. We and immigrants alike. In fact, we need [say these neoclassical economists, as evidenced by the link to The Economist] more immigrants for more entrepreneurial spirit, cheaper labor, and higher demand for the existing products. And remember, ‘a rising tide lifts all boats’.”

The very next paragraph starts, “The neoclassical firmament is cracking, though…”

Perhaps you should have kept reading after all (albeit a bit more carefully).

Be careful of the context with short quotes – I think you may have inadvertently interpreted Brian’s remarks as standing for exactly the opposite of his message in this article.

You can get the essence of the article by reading the last three paragraphs of the article – you’ll get a much better sense of what Brian and Steady State Economics would like to see happen.

1. There are troubling aspects to this post. Let me quote two snippets.

“The steady-state nation must tighten its borders to the degree that population is stabilized, but only while transitioning to a steady state economy. At the same time, it must lend a helping hand to impoverished regions, essentially in lieu of welcoming the emigrants thereof. In many cases, the helping hand would amount to a better deal for the impoverished, too, for how many among them would really want to leave their homeland, if only conditions were better there?”

“In cases of natural disaster and ecological deterioration due to global heating, such as sea-level rise, the Aid-In-Place Fund would assist (in concert with the U.S. Foreign Service) with relocation to ecologically and culturally similar regions.”

First, let me state my agreement with the notion of doing what we (blobal North) can to help improve conditions in other regions to lessen the desire/necessity of residents to flee. We haven’t done a great job of that. Ever. As far as I can tell.

Second, this is a very parochial (and entitled?) response to a global problem and it is therefore very surprising to read it in this blog.

Third, it downplays significantly the likely impacts of environmental degradation which will, most likely, provoke a massive flood of environmental refugees. Also, the notion that we should help “with relocation [of refugees] to ecologically and culturally similar regions” is simply bizarre. First, ecologically similar obviously means another region in crisis. It also ignores the fact that environmental degradation is a global crisis; it is “only by the grace of [deity of choice]” that we find ourselves as residents of the “global north”.

2/

In North America, we also have the benefit of two wide moats that a priori provide us relief from acute waves of refugees (the continuing immigration from Central America and Mexico notwithstanding – and how much of that, in any event, is the result of American political actions in the region?), such as has occured in Europe, for example, over the past decade.

It’s a wicked problem but don’t think that any nation can think themselves so pure as to be able to sit above the fray.

Not to mention that the majority of the GHG emissions have been from nations in the global north, which nations you counsel should insulate themselves from the future waves of environmental refugees that they, in fact, will have had a major part in creating.

The essential policy foundation of this article is the closest I’ve ever seen to a rational approach to an immigration issue that has no structural solution in the world as we know it. Judging by the comments so far, the article could be a springboard for a healthy debate. Here’s my question. In 1954, the USA engineered a coup to overthrow the democratically elected president Arbenz in Guatemala. The long-term consequences for Guatemala included brutal dictatorships and wrenching economic policies determined by the United Fruit Company. In theory, some degree of Guatemalan immigration to the USA could be traced back to that coup and subsequent American interventions. Similarly, Algerians immigrating to France may be a rebound from French colonialism. How many rural Mexicans have crossed into the United States as the result of NAFTA policies. Or Haitians coming here because of the holy mess Bill Clinton made with the Haiti earthquake relief fund. I am sure that a steady statesman or woman in power would have humane and equitable ways to address these contradictions, and this is why I think Brian’s article could be a springboard for a healthy discusssion.

I agree – one thing I had not realized until a number of years ago is that NAFTA put many simple subsistence farmers in Mexico into dire straights. Their life revolved around growing and selling corn. A flood of industrially produced US corn wiped them out.. leaving them with not much choice but to trek North and try to find some kind of paid work in the USA.

Alas, we have a bad habit of not thinking through, or perhaps taking responsibility for, the unforeseen consequences of things we create.

Your example of Mexican farmers hits a home run for me, since I’ve known some of them, and even worked with them. Brian’s idea of aiding these people in their own countries is essential. In the case of corn farmers or victims of unforeseen consequences, I would call this “restorative aid”, but rather than fight for a phrase, I’m happy with this steady state solution as it stands.

Thanks Brian, this is a really good treatment, with a lot of wisdom and holistic thinking, of a very touchy subject. Independently I’ve concluded for some time exactly the same things: if we in developed countries ignore problems in other parts of the world, eventually those problems will affect us.

Reaching out to *help* poorer societies become less poor is one of the few win-win policy objectives out there. I think it’s fair to say that even a healthy young man does not walk 1000 miles from Guatemala or Syria because it’s fun, or easy, or because it’s a lark. Desperate circumstances drive desperate actions.

Letting people know that help is on the way, and that long term, they should see their familiar homeland become a much better place to live, is absolutely the right thing to do on many levels. Thanks again for pointing this out so eloquently.

Great article Brian and so relevant for us in Australia too.

I question the figure of 2.1 for replacement fertility, particularly where life expectancy continues to increase so previous generations remain alive while more young people are born and reach reproductive age. Where less than 10% of people die before they reach reproductive age a fertility rate of much closer to 2.0 should stabilise the population.

Thanks for this insightful, intelligent, compassionate essay, Brian. It reminds me of the Clinton Commission on Sustainable Development’s “Population and Consumption Task Force” which said the exact same thing back in the ’90s. See here: https://clintonwhitehouse4.archives.gov/PCSD/Publications/TF_Reports/pop-pref.html

All best, and keep up the great work.

Gary

Thank you Gary. I appreciate the compliment.

That said, I should clarify that Clinton’s Council on Sustainable Development and the task force you noted (there were several task forces among the Council) did not say “the exact same thing” as the whole of my article. The Population and Consumption Task Force did call for stabilizing population, but not for establishing a steady state economy. That’s profoundly distinct from steady statesmanship, as I emphasized in the final section of my article.

It’s true that some of the participants with the task force were inclined to be steady staters—Robert Repetto, for example, became a CASSE signatory in 2010—but as Crescencia Maurer reported in her case study of the Council (http://pdf.wri.org/ncsd_usa.pdf), the “task forces were at the center of the most difficult as well as inspiring discussions: balancing economic growth with conservation and equity concerns.” Nowhere in any of the Council or task force documents (or reports thereon) have I seen any acknowledgement of limits to growth or the need for a steady state economy, although I’d imagine these topics came up at task force meetings. (And, I haven’t scrutinized every single document, some of which are hard to track down now.)

In any event, the Clinton Administration as a whole was famous—or infamous to steady staters—for the win-win rhetoric that “there is no conflict between growing the economy and protecting the environment.” I witnessed and experienced the legacy of that for years in my position with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Many DOI officials actually believed the rhetoric. Others saw through it but rode the political wave it created for them.

Anyway, thanks for joining the conversation, and you too keep up the great work! At CASSE, we are very grateful for your chapter leadership.

Thanks for addressing the issue of immigration limits. It is central to earth’s carrying capacity, sustainability and human survival. Yet it is avoided like the plague by nearly all environmental, governmental, and political organizations.

I’ve also concluded that the wisest approach to helping potential immigrants is to support them in their country of origin — so that they do not break up their families, take great risks and break laws to immigrate. People in developed countries need to think and resist the emotional urge to engage in the “pathological altruism” of unlimited immigration.

Aid in Place needs to become a commonly used term. And as pointed out decades ago by environmentalist David Foreman, one the worst things for planet sustainability is people immigrating from low resource using countries to high resource use countries while keeping their traditional high reproduction rate.

Excellent and concise, thank you. I’ll have to remember that phrase, “Aid in Place.” It’s better for all concerned.

On Rosalie Schultz question about replacement fertility rates, I’ve recently seen 2.075 in developed countries. The reason it is more than two and always will be, is that some do not survive to adulthood, so it takes more than two to replace two parents. A few are sterile and produce no kids. In the best countries, nearly 2 in 1000 babies born die in the first year of life (the U.S. is way down the list with about 6 per 1000 infant deaths). In the worst countries over 50/1000 die in the first year. In those countries, replacement fertility is a couple of tenth’s higher, maybe 2.3 kids/woman. A reasonable number to use, I think, for a global average is still close to 2.1. This number we are quoting is a statistic called total fertility rate that is a cross sectional measure at a point in time, obtained by summing births in a given year. So it tracks changes well.

The win win solution to migration is cutting birthrates in source countries. This is the “Norwegian Solution.” Norway sent 400000 to the U.S. before their birthrates dropped and Norway got rich. Now net migration from Norway (and all of Europe) is near zero. So we should offer family planning aid to help improve the status of women in high fertility countries.

On the more general issues, I very much liked Brian’s efforts to sort this complicated issue out rationally. My immigration lawyer cousin reminds me that immigrants are people with unalienable human rights. My dad was an immigrant. But we don’t live in a perfect world. We live in a world where if we had open borders probably a billion people, many from countries with much higher fertility rates than ours, would probably want to come to the U.S.A.

“The win win solution to migration is cutting birthrates in source countries.” Yes, that is the only sustainable path forwards. PMC do great work with edutainment on TV and radio populationmedia.org

Thank you for this article Brian, a perspective that is often lacking in this very reactive and dichotomous debate.

It resonates with my a couple of my perspectives, that being:

– That open borders is a nice idea in theory, but only when there is a degree of global equity in place. It is something to perhaps aspire to while recognising that it is impractical at this point in time, particularly when when there are so much variability between countries, not least the access to reproductive and family planning health care.

– I’m paraphrasing author Derrick Jensen a little hear, but he shared a perspective not long ago that if the USA restricts immigration, it must be conditional that it attempts to live within its means (i.e. that it doesn’t continue to extract resources from the countries it is restricting immigration from).

– I agree that there will be an increading exodus of people from the global south to the global north resulting from climate change and environmental catastrophe. But isn’t this even more of an argument to the fact that we should do away with economic migration in the mean time? So that host countries have more ‘give’ in terms of being able to accomodate people, downn the track, who need to migrate because they have to? Economic migration, but constrast, is a movement of people based on preference and narrow economic ideologies.

-Anyway, there will be a limit to the extent to which ‘global north’ countries can continue to hold their own populations, let alone others. Is it not true that the reduced snowfall around Colarado will impact the viability of millions of people in the Mid-West?

Up until World War II, America had a need for immigrants. There was a need for immigrants to build cities, infrastructure, schools, homes, railroads, hospitals, highways, etc. West of the Mississippi River there was a vast expanse and natural resources were not in danger of being depleted. Today, it is much different. Our cities, schools, highways, hospitals, are overburdened, overpopulated, congested, crowded. Taxes are raised to accommodate immigrants, legal and illegal. We must close the doors, for we can no longer accept or absorb more people. There is only so much air that one can get into a balloon. Overinflate, and it explodes.

This is a reasonable position. I support all parts of it, including more generous aid to poor people overseas. However, two caveats.

First, we need decreased populations, worldwide and in the US, to achieve sustainability. Not stabilizing at our current bloated numbers.

Recent estimates of a sustainable global population run between two to three billion people, depending on how optimistic researchers are about international cooperation to solve wicked collective action problems. Examples include Theodore Lianos and Anastasia Pseiridis, “Sustainable Welfare and Optimum Population Size,” 2016; Christopher Tucker, A Planet of 3 Billion: Mapping Humanity’s Long History of Ecological Destruction and Finding Our Way to a Resilient Future, 2019; Partha Dasgupta, Time and the Generations: Population Ethics for a Diminishing Planet, 2019; Lucia Tamburino and Giangiacomo Bravo, “Reconciling a Positive Ecological Balance with Human Development: A Quantitative Assessment,” 2021.

It might be rhetorically more effective to call for population stabilization than population reduction. Nevertheless, we appear to need much smaller populations to have a fighting chance to create sustainable societies.

Second, we can’t solve all the world’s problems. Nor can we allow creating a sustainable society in the US to depend on whether peasants halfway around the world have fewer children, or their leaders suddenly discover and embrace western ideas about government furthering the common good (rather than being a vehicle to enrich their families or ethnic group).

Creating a just and sustainable society here in the US is challenge enough. To do that, we need to reduce our bloated population, and to do that, we need to reduce immigration. A lot. That’s in addition to building a new economy around “enough” rather than “more.”

We need to reduce legal immigration by 90%, end the H and L work visa programs, and mandate E-Verify for all employers. We also need to aggressively support family planning programs in the Third World.

It should also be pointed out that the Third World is far from being without responsibility in ecological degradation. The rapid population growth in the Third World, and overpopulation in rapidly industrializing nations like China and India, have destroyed a huge quantity of forests and wildlife habitat. This has exacerbated climate change. The First World has certainly done its share of damage, and continues to do so by various inactions such as the refusal to replace fossil fuel power generation with nuclear power. However, the Third World is far from innocent here.

Congratulations, Brian and CASSE for a positive way forward on immigration.

We in the post-industrial world need to be careful when assuming responsibility for conditions in developing countries, lest it takes their agency from them. The helping hand in lieu of immigration would indeed be a better deal for them because it could be targetted [sic] at the truly needy who can’t afford to go an an emigration adventure to upgrade their lifestyle and escape overcrowding and environmental degradation. In Australia, having ‘stopped the boats’, we now have a lot of Indian immigrants flying in who, I can attest, are sometimes coming from conditions that are actually better than the conditions they find themselves working in (albeit temporarily) here. A certain level of opportunism is healthy, but I believe we have well and truly come into a global culture of self opportunism. “Ask not what you can do for your country, ask what the planet can do for you.” The growth mentality is alive and well in countries like India where the burgeoning population is regarded as an asset and a form of leverage for global influence via its diaspora. Turning off the tap of migration would compel countries with growing populations to deal with their fertility – something post-industrial countries could also target aid toward, as we did mid-last century with very effective, non-coersive [sic], popular family planning programs. The Catholic Church put a stop to that.

What are you thoughts on RFK Jnr? At least he’s ecologically literate.