CO2 Emissions: Accounting for Accountability

by Taylor Lange

In my very first graduate statistics course, the professor often cautioned us about data collection: “Garbage in, Garbage out.” What she said, in no uncertain terms, was that mistakes in the measurement or methodology would invalidate our statistical analyses. I’ve consistently reminded myself of this mantra. My colleagues, students, and I double check the sources and methodology behind any data we’re testing. If we aren’t entirely confident in the integrity of the data, we toss it into the garbage instead of using it to propagate further garbage.

At CASSE, we’ve noticed some changes in the accounting methods used to tally CO2 emissions. Uncannily, these changes seemed to take root around the same time CO2 emissions were shown to decline in the USA. We were immediately skeptical, because extremely powerful interests would benefit from a display of declining CO2.

After an investigation of the scientific literature, the answer turned out to be a bit more complex than we previously imagined.

U.S. Emissions by the Number

In April, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) published an inventory report on greenhouse gas emissions and sinks in the USA from 1990-2019, and it suggests some cause for cautious optimism. Emissions rose steadily from 1990-2007, then reversed course and have declined ever since. As of 2019, U.S. emissions are only 1.8 percent higher than they were in 1990, due primarily to decreased energy use stemming from innovation and conservation efforts.

Economic globalization has allowed embodied emissions to travel around the world. (CC BY-SA 4.0, Caitlin Duffy)

The inventory is a synthesis of annual reports that the EPA prepares pursuant to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Ratifying nations of the UNFCCC agree to estimate greenhouse gases with global warming potential emitted within their boundaries so that a global assessment of greenhouse gas emissions can be made. The primary concern is CO2, due to its major role as a greenhouse gas, and as a standard by which other gasses are measured for their potential to trap heat in the atmosphere.

This method of estimating global emissions makes the simple but important assumption that each country is responsible for the greenhouse gasses emitted within its boundaries. Experts[i] began questioning this assumption in the late 2000s because it omits a crucial step in the supply chain: global trade.

Focusing on CO2, let’s explore how discounting the consumption of goods—foreign or domestic—can bias our understanding of who is responsible for emissions. We can then examine how a more thorough understanding of emissions accounting can empower consumers to reduce their own emissions.

Production-Based (Territorial) Accounting

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) guidelines[ii] suggest countries measure CO2 emissions associated with five categories:

- Energy: This includes all fuel combustion related to transportation, electricity production, and residential uses (such as lawn mowers), the extraction of fuel (such as coal mines), etc.

- Industrial Processes and Product Use: This entails emissions from producing materials such as iron, steel, and cement, and other intermediate and final goods.

- Agriculture: These emissions are a result of soil management (such as the application of fertilizer), and livestock production.

- Waste: This includes CO2 released through trash decomposition, sewage water treatment, and composting.

- Land Use, Land Use Change, and Forestry: This mixed category includes emissions and sinks from forests, croplands, grasslands, etc. While deforestation and various land uses do emit CO2, the CO2 stored in plant growth usually makes this category net negative.

Taking stock of emissions in this manner is referred to as “territorial” or “production-based” carbon accounting, though the term “production” can be a bit misleading. These are actually emissions that occur during the extraction of natural resources, the production of goods, and their transport to market within the country. Production-based accounting does, however, account for some global trade by estimating “bunker fuels,” which are emissions from shipping vessels that depart from a territory.

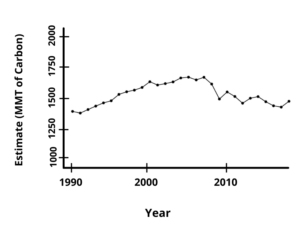

Figure 1. U.S. carbon emissions, measured in million mega tons of carbon. Data from the Global Carbon Project. These data do not include estimates of bunker fuels.

U.S. emissions from 1990-2018 were charted by the Global Carbon Project, a consortium of scientists who use the UNFCCC’s data to calculate and annually publish the global carbon budget in the journal Earth System Science Data[iv]. U.S. emissions steadily declined from 2007-2018 (Figure 1), but how would this story change if we were to consider the implications of global trade?

Consumption-Based Accounting

An alternative to production-based accounting is consumption-based accounting, which was founded on two observations:

- Goods have an emission “cost.” Emissions are released throughout the supply chain, from extraction of natural resources to the energy used transporting products to retail outlets. This suggests emissions are “embodied” in final goods[v].

- Because consumer demand drives supplier behavior, consumers bear substantial responsibility for embodied emissions. Production-based estimates include the consumption of domestic goods, but not all goods produced in a country are consumed in that country. In consumption-based accounting, estimates are adjusted based on embodied carbon in exports and imports. In 2004, for example, 23 percent of global emissions were embodied in goods consumed in other countries[vi]. The USA, Japan, and many European countries were the largest importers of carbon, while China, Russia, and India were among the highest exporters.

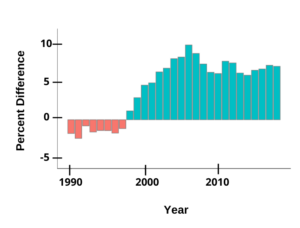

Figure 2. The percent difference between production (red) and consumption-based (blue) estimates in the USA from 1990-2018.

When global trade is considered, the data depict a slightly different story. Until 1998, the USA was actually responsible for less CO2 because more embodied carbon was exported than imported (Figure 2). However, in 2005 and 2007, the USA was responsible for 7.4 percent and 7.8 percent more emissions, respectively. By accounting for imports and exports, we realize that U.S. consumers are significant contributors to annual emissions.

Accounting Methods Matter

Consumption-based accounting not only reveals a country’s real contribution to the problem, but also the country’s capacity to change.[vii] Imagine that a company in an affluent country decides to outsource a carbon-intensive part of its supply chain to a developing country. While this may benefit the developing country’s economy, this decision also reallocates the carbon emissions from a rich country (with the means to invest in cleaner production methods) to one with fewer resources. Consumption-based accounting helps remedy this ethical dilemma by holding accountable countries with greater regulatory power and higher per capita emission consumption.

Consumption-based estimates are only useful if we address how carbon-intensive our consumption actually is.[viii] Consumption-based accounting suggests that we—consumers—play a vital part in effecting change. Here are some things you can do:

- Reduce your consumption. Adopt a philosophy of minimalism and be conscious of embodied emissions, especially in food.

- Choose brands that have reduced the carbon cost in their supply line. Carbon Trust has eco-labeling certifications for identifying carbon-neutral products.

- Advocate for consumption-based accounting alongside production-based accounting. Different data serve different purposes, motivate multiple actors, and result in complementary reforms.

Moral of the Story

While consumption-based accounting may arguably lead to a fairer assessment of emissions, justice is a moving target. The age-old question arises about who really drives the economy: producers or consumers. Was Say’s law ever truly debunked? And don’t producers—augmented by their Madison Avenue advertisers—“produce” demand as well as goods?

The whole discussion evokes the chicken:egg causality puzzle. Which comes first? What is not in dispute is that we have far too much “chicken” and just as much “egg,” all proliferating in lockstep and emitting greenhouse gases along the way. With GDP growth as the central economic policy, production and consumption are even more relentless.

Perhaps the greatest hope for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, then, is not with accounting practices, but starting with the right policy goal. After all, it’s “garbage in, garbage out.”

Footnotes

[i] Steven J. Davis and Ken Caldeira, “Consumption-Based Accounting of CO2 Emissions,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, no. 12 (March 23, 2010): 5687–92, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0906974107.

[ii] IPCC, “2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories” (Japan: National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme, 2006)

[iii] Global Carbon Project, “Supplemental Data of Global Carbon Budget (Version 1) [Data Set],” Global Climate Project, 2020, https://doi.org/10.18160/gcp-2020.

[iv] Pierre Friedlingstein et al., “Global Carbon Budget 2020,” Earth System Science Data 12, no. 4 (December 11, 2020): 3269–3340, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-12-3269-2020.

[v] G. P. Peters, S. J. Davis, and R. Andrew, “A Synthesis of Carbon in International Trade,” Biogeosciences 9, no. 8 (August 23, 2012): 3247–76, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-9-3247-2012.

[vi] Steven J. Davis and Ken Caldeira, “Consumption-Based Accounting of CO2 Emissions,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, no. 12 (March 23, 2010): 5687–92, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0906974107.

[vii] Karl Steininger et al., “Justice and Cost Effectiveness of Consumption-Based versus Production-Based Approaches in the Case of Unilateral Climate Policies,” Global Environmental Change 24 (January 1, 2014): 75–87, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.10.005.

[viii] G. P. Peters, S. J. Davis, and R. Andrew, “A Synthesis of Carbon in International Trade,” Biogeosciences 9, no. 8 (August 23, 2012): 3247–76, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-9-3247-2012.

Taylor Lange is the ecological economist at CASSE.

Taylor Lange is the ecological economist at CASSE.

Good article, Taylor. I write to call your attention to an egregious statistical error coming from the United Nations and on down, the underestimation of emissions from forest practices. Here are some references:

• Center for a Sustainable Economy, Oregon Forest Carbon Policy: Scientific and technical brief to guide legislative intervention (https://sustainable-economy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Oregon-Forest-Carbon-Policy-Technical-Brief-1.pdf).

• Center for a Sustainable Economy, Clearcutting our Carbon Accounts: How State and private forest practices are subverting Oregon’s climate agenda (2015) (https://sustainable-economy.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Clearcutting-our-Carbon-Accounts-Final-11-16.pdf).

• Ecosystems Climate Alliance (Global Witness, The Wilderness Society, Rainforest Action Network and Wetlands International), Deconstructing LULUCF and its Perversities: How Annex I Parties Avoid their Responsibilities in LULUCF (Rules Made by Loggers for Loggers (www.wetlands.org/publications/de-constructing-lulucf-and-its-perversities/) (2018).

• Carl Segerstrom, Timber is Oregon’s biggest carbon polluter :A new study finds that forests are key to reducing the state’s climate impacts”, High Country News, May 16, 2018 (www.hcn.org/issues/50.11/climate-change-timber-is-oregons-biggest-carbon-polluter).

• Beverly E. Law, et al, “Land use strategies to mitigate climate change in carbon dense temperate forests” (www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1720064115 ).

Hi David,

Thank you for pointing this out for us. We’re looking at forest management practices another project and these are great resources to look at!

-Taylor