To Be or Not to Be: Is the European Degrowth Movement Courting an Identity Crisis?

by Brian Czech

To be or not to be

for lowering GDP.

Deciding is the fee

for degrowthers to be free!

(Free of confusion, that is, and degrees of self-defeat.)

In the heart of the Cold War, John F. Kennedy proclaimed, “Ich bin ein Berliner.” More than halfway to a century later, my solidarity is with a different European ideology, which traces its roots to the French scholar Serge Latouche. I say, “Je suis pour la décroissance.”

Shakespeare would have a question for degrowthers. (Image: CC0 1.0, Credit: The Washington Times)

Yes, I am a degrowther, secondarily at least. I prefer to identify primarily as a steady stater, but by now—well into the 21st century—we steady staters realize the global economy is almost certainly beyond its long-term capacity. No one in steady-state economics is advancing the notion of a perpetual, pre-covid $88 trillion economy. In other words, we’re all for “degrowth toward a steady state economy.”

In many ways, steady staters were the original degrowthers, with Herman Daly at the forefront since the 1960s. I joined the pack around 1995, in the midst of my Ph.D. research, which included an interpretation of the Endangered Species Act as an unintended prescription for a steady state economy. As the author of the CASSE position on economic growth (with input from Daly and others), and as alluded in the last two clauses thereof, degrowth was on my radar more than 20 years ago.

In the “old days,” though, the degrowth movement in English-speaking circles often went by another slogan, “contraction and convergence.” Informed by yet other steady staters—notably the ecological footprint trackers Bill Rees and Mathis Wackernagel—scholars started calling for a contraction of the global economy before striving for a steady state. Knowing such contraction wasn’t politically viable globally without the spreading of some wealth from richer to poorer nations, they coupled the concept of contraction with the concept of convergence. A convergence of wealth, income, and opportunity was required if there was to be any hope for “steady statesmanship” in international diplomacy.

Why bother with the mini-history? Because there seems to be a peculiar notion (to be explored shortly) coming out of pockets of the degrowth movement, particularly in Western Europe. In my opinion, it’s a notion that threatens the credibility and effectiveness of the broader non-growth or post-growth movement. Therefore, it becomes important at this stage to wrangle a bit on the identity and future of the movement.

Such wrangling should start with the realization that no one has a monopoly over the word “degrowth.” While the socially constructed Wikipedia might relay the notion that “degrowth” is “a political, economic, and social movement,” in reality, “degrowth” is a word, and a word with a perfectly clear meaning. The political, economic, and social program entailing degrowth can rightly be called a “degrowth movement,” but not “degrowth” per se.

Degrowth: The Meaning vs. the Movement

Hearkening back to our Shakespearian poem, and speaking as an original degrowther, I for one don’t have any doubt. Why of course I’m for lowering GDP! Not recklessly, draconianly, or stupidly. But certainly and significantly. Why deny it?

Yet many degrowthers—or many who identify themselves thusly—seem quite agnostic about GDP degrowth. Some readers are probably wondering, “Seriously? Can there actually be degrowthers—people calling for degrowth—who deny that degrowth entails a declining GDP?” And who could blame the poor reader, as the very first metric that would come to most minds, when thinking of degrowth, would indeed be GDP. From the Cold War to Brundtland Commission win-win rhetoric to Trumpian politics identifying GDP growth as Goal #1, growth has always been about GDP! When growth is all about GDP, why certainly degrowth would be all about GDP, or at a minimum decisively in favor of declining GDP!

Might I be making a mountain of a molehill? I don’t think so. Maybe a knoll from a hummock, but even a hummock is an obstacle, and hummocks have potential for growing into knolls.

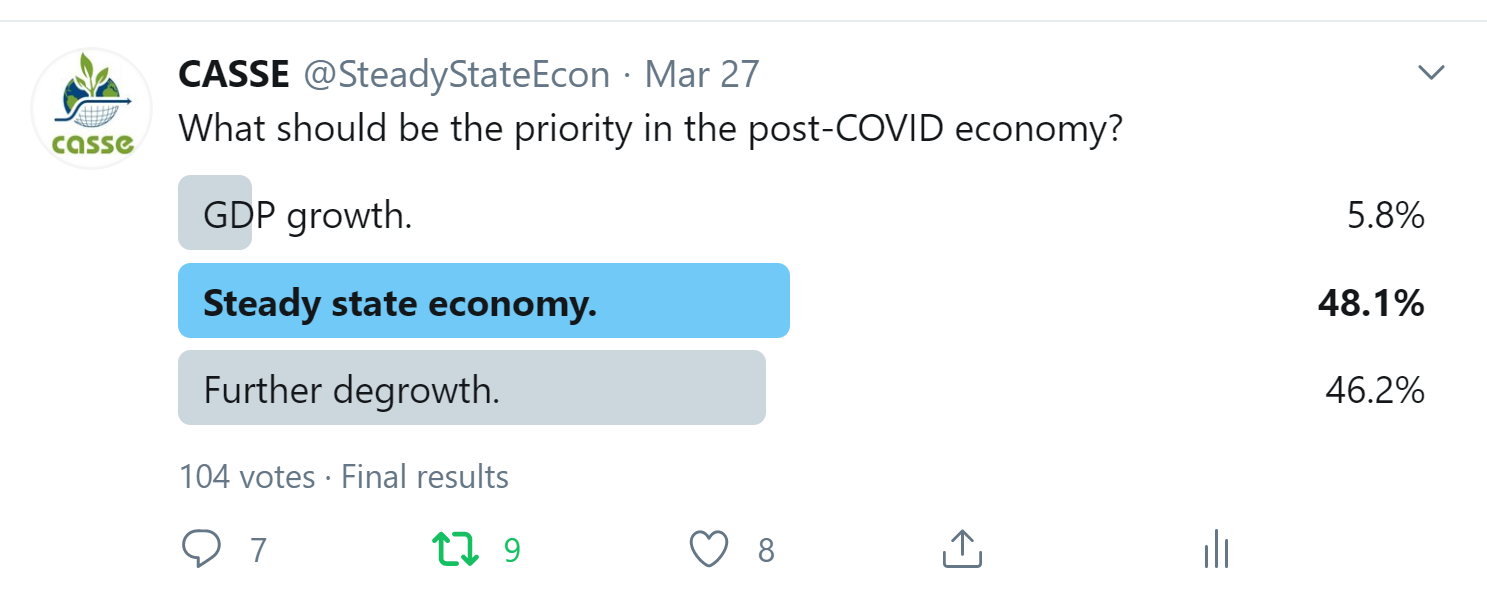

As evidence for the hummock, I would like to quote a degrowther (who shall remain anonymous) who replied to a tweet in which CASSE polled the Twittersphere, “What should the priority be in the post-COVID economy?” First, let’s consider the poll results:

Of course the poll was not conducted with Pew-like research methods and standards. CASSE is followed on Twitter largely by those who get it about limits to growth, so no one would claim the results to be representative of the general public. Furthermore, the difference between steady-state and degrowth votes is statistically insignificant. The key point here, though, is not so much the tally, but rather some verbal responses to the poll and to the covid-caused recession in general, starting with the aforementioned, anonymous degrowther.

The degrowther stated in an email, “What this tweet suggests is that the current situation of economic crisis corresponds to degrowth. The problem is not just that this statement is inaccurate since degrowth does not equal less GDP, but also that it is damaging to the advocacy work that we do here…” (emphasis added).

The full email suggested that the quotee is no muddleheaded green growther, but rather a reputable and scholarly degrowther, and perhaps something of a leader in the field. Therefore, I do not think the quotee was implying, much less believing, that degrowth is congruent with a growing GDP. Rather, I think the quotee was striving to emphasize—and wanted others to strive likewise—that, in the European degrowth movement, “degrowth” is supposed to connote far more than a decreasing GDP, including a thorough political package of social justice. Unfortunately, however, the language used to de-emphasize GDP is often confusing and too inconclusive about the need for lowering GDP.

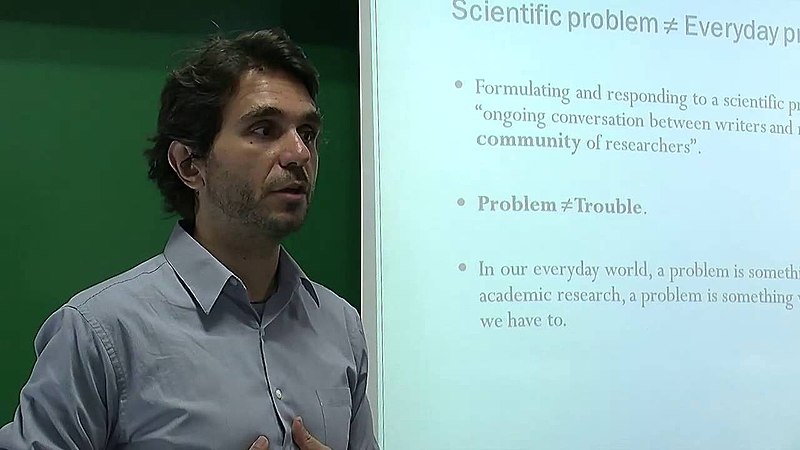

One degrowth leader, Giorgos Kallis, doesn’t offer much clarity, at least not in writing, by insisting that “Degrowth is anything but a strategy to reduce the size of GDP.” Similar to the anonymous quotee, he surely doesn’t believe in “green growth,” as the corresponding video (and recent scholarship) helps to clarify. Yet he wants the degrowth movement “to be distinguished from recession or depression” so much that he downplays the need for declining GDP.

A similar lack of enthusiasm for lowering GDP is found in the article, “Their Recession Is Not Our Degrowth!” The author, Federico Demaria, wrote about degrowth, “Our proposal is not necessarily to reduce GDP (an arbitrary indicator), but rather to ask new questions and search for alternatives to today’s society based on a predatory, unjust and unsustainable capitalist economic system.”

The Significance of GDP in Growing, Degrowing, and Steady State Economies

If Mark Twain were a steady stater (which would not be surprising), he might apprise, “The reports of GDP’s arbitrariness are greatly exaggerated.” In fact, GDP is perhaps one of the least “arbitrary” of all the macro indicators on Earth. GDP growth has been soberly and deliberately (albeit unwisely in recent decades) selected as a central economic policy goal for close to a century. The outcomes are far from unclear, either. GDP serves as an indicator of dozens or hundreds of things, and it is a rock-solid indicator of at least five:

Giorgos Kallis, European degrowth leader. A Shakespearean steady stater might opine, “Kallis doth protest too much, methinks.” (Image: CC BY-SA 4.0, Credit: Riccardo Mastini)

- Energy and material throughput

- Pollution

- Biodiversity loss

- Environmental impact

- Ecological footprint

Now this isn’t the article for refuting the increasingly irrelevant neoclassical growth economists who believe in perpetual GDP growth. That can be and has been done in many other venues. This is an opportunity, on the other hand, for squaring up degrowth and steady-state messages. Let’s start with the five points noted above.

The trophic structure of the human economy establishes that a growing GDP requires increasing throughput, even with technological progress. Pollution is an inevitable function of the second law of thermodynamics, and increases with GDP. The causes of biodiversity loss are like a Who’s Who of the economy. Biodiversity is in turn the top indicator of ecological integrity and environmental health, which decline as the economy grows. We might even view the economy as an $82 trillion giant, stomping across the landscape, leaving its ecological footprint.

In addition to the five points above, it’s no stretch of common sense—much less sound science—to identify tight linkages between GDP and:

- Noise

- Traffic

- Stress

- Soil depletion

- Water shortages

- Competition for resources

- International strife

- War

Then, of course, we have greenhouse gas emissions, climate change, and sea-level rise. While neither Kallis nor myself think there’s a Thanksgiving turkey’s chance of decoupling today’s GDP from greenhouse gas emissions, even a “renewably” energized future is hellish enough, given the relentless efforts to push GDP perpetually upward.

So, does anyone still feel like ignoring GDP? Or downplaying the importance of degrowing it? Here then is one last try to get us over the hump.

The GDP Question in the Politics of Degrowth: We Can Handle It

Assuming we truly do want a decreasing GDP—which we desperately need for the sake of environmental protection, economic sustainability, national security, and international stability—we must strive for it as politically effectively as possible. For degrowthers in western Europe, apparently this entails assuaging the concerns of those who want “degrowth” to automatically connote goodness, or at least improvement from current badness. Connoting goodness or improvement is a tough sell when the public is accustomed to thinking of improvement (if not goodness) in terms of a growing GDP. But that’s our job!

One subtle approach is Timothée Parrique’s proposal (page 326 of his Ph.D. dissertation) for distinguishing linguistically, and thus connotatively, between “degrowth” and “de-growth.” The unhyphenated “degrowth,” then, would connote the broader degrowth movement and all it stands for. “De-growth,” on the other hand, would be limited to the trend in GDP.

Parrique’s approach resonates with CASSE, as we have long distinguished between the “steady-state economy” of neoclassical economics and the “steady state economy” of ecological economics. In the hyphenated phrase of neoclassical economics, “steady-state economy” connotes simply a stabilized capital:labor ratio, and almost always with growing GDP! In the non-hyphenated phrase favored by CASSE, “steady” modifies “state,” and “state” modifies “economy.” In other words, “steady state economy” connotes a political state in which GDP is stabilized.

Our attempt to distinguish, via hyphen, between neoclassical and sustainable concepts would be well understood in only a tiny corner of academia where political science and ecological economics meet (and where neoclassical economists rarely interlope). Outside of that corner, any effects would be marginal. The hope, though, is that neoclassical growth theory will fade far enough away as to leave the “steady state economy” as the only entry that really matters for purposes of politics and policy, even if “steady state” is occasionally or inadvertently hyphenated.

Similarly, I suspect Parrique’s distinction will be understood only within the tight confines of the academic degrowth literature. Outside those confines, especially all the way into public dialogue, “degrowth” will be used just as it sounds and—pursuant to the “Commoner’s Dictionary”—just as it means: Decreasing and, in particular, decreasing GDP.

The bigger point is, that’s not a bad thing! It is decidedly, decisively a good thing in the 21st century. We want GDP degrowth, all the way back to a sustainable and ideally an optimal steady state economy. Of course, it’s not the ultimate end-all goal, but it’s much more than a trivial means to an arguable end. GDP degrowth is such a necessary condition for sustainable wellbeing, it’s crucial that we strive for it.

So, if degrowthers are worried about the tarnishing of their message with the connotations associated with recession, coronavirus, or a covid-caused recession, my response is: That’s life. It’s not easy. It will take plenty of political prudence, and tireless determination, to advance the steady state economy—or degrowth toward a steady state economy—as the central economic policy of the 21st century. We have to learn how to communicate, with clarity if not flair, what Herman Daly has long emphasized; namely that a failed growth economy is not the same as a successful steady state (or successfully degrowing) economy. I think we can do it, but not if we waffle on the need to degrow GDP, which only confuses observers and allows for the persistence of “green growth” fantasies.

Je suis pour la décroissance. That’s right, I am a degrowther. And I’m all for GDP degrowth!

Brian Czech is the executive director at CASSE.

I appreciate the update on the Euro degrowth movement. I can vouch for one branch of the French degrowth movement, La Décroissance: le Journal de la joie de vivre. I’ve never seen them waver about GDP. I can understand how some “mainstream” degrowthers debate about which terminology they should use, but La Décroissance is so unbudging, that they are seen by others as sectarian. Serge Latouche is still in good standing as is Ivan Illich. The critique in Planet of the Humans against growth-oriented environmentalists pales in comparison to what La Décroissance does to anyone who dabbles in GDP-type concessions. This journal only appears in print, and only in French. You can find it at most newspaper-magazine kiosks. Most of us will find something we are doing wrong somewhere in their pages. They are both merciless and fun to read.

Thanks for the insights Mark. I wish we had such a journal in the USA, especially now!

Brian provided the following potted history’: ‘In the “old days,” though, the degrowth movement in English-speaking circles often went by another slogan, “contraction and convergence.” ‘

No, the concept of Contraction and Convergence was developed by the Global Commons Institute specifcally for greenhouse gas emissions. It should not be confused ‘degrowth’ which refers to consumption in general. It’s possible to have Contraction and Convergence without degrowth and it’s possible to have degrowth without Contraction and Convergence. That’s a key problem!

After another thirty years of ‘Expansion & Divergence’, either we return to the original meaning of C&C – neg-entropy or ‘organic growth’ – or we’re done for.

Either way the American Dream is done for: –

http://www.gci.org.uk/Symmetry_Binding_Properties.html

It appears to me that showing the difference between our current pandemic driven recession and degrowth can simply be highlighted through the difference between unexpected in the first case and planned or managed in the latter.

I would go so far as to say with proper planning and preparedness we could also reduce some of the negative impacts of pandemics while managing degrowth and eventual steady state economics.

Management also requires metrics such as GDP, and likely a plethora of new ones to track and achieve steady state economic goals, as well as control mechanisms over the current Wild West of “free market economics” and the growth religion.

How much better could the Marxist planned economies have performed if they had today’s computing and telecommunications technologies?

Great discussion

You sure packed a lot into four sentences! Regarding only the first one, though, why not say something like, “Covid-caused degrowth is not the same as healthy degrowth.” The former is still a case of degrowth, but hard-luck degrowth. The latter is, as you say, planned out and therefore a healthy success of the degrowth movement.

FYI our plan is starting to take shape in the Full Seas Act:

https://steadystate.org/a-post-covid-vision-the-full-and-sustainable-employment-act/

thanks for the article. I think it was Paul Ehrlich I heard say in a lecture that environmental disasters such as the Exxon Valdez ADDED to GDP, not because of the problems they caused but because of all the economic activity generated to clean them up. Alternatively, recent studies have shown that the way Amazonian first peoples have managed the rain forests has Increased biodiversity, reducing negative ‘environmental impact’ whilst enabling the extraction of resources. Modern Permaculturalists and some agriculturalists promote ‘regenerative’ practices that aim to improve the ecosystem whilst enabling extraction for human use.

Whilst far from main stream (and many are anti-mainstream and would happily advocate reduced consumption, increased reuse etc), could it be possible to alter human activity in such a way as to Generate increased environmental ‘goods’ whilst also extracting what’s needed for human civilization?

Permaculture “a creative design process based on whole-systems thinking” https://permacultureprinciples.com/

Farmers on the Frontlines of the Regenerative Agriculture Transition https://www.conservationfinancenetwork.org/2020/04/15/farmers-on-the-frontlines-of-the-regenerative-agriculture-transition

Innovation by ancient farmers adds to biodiversity of the Amazon, study shows https://phys.org/news/2020-06-ancient-farmers-biodiversity-amazon.html

I am with Brian on this. I know the GDP needs to shrink and I occasionally remind my colleagues when they are thinking about how to the legislature that the efficiencies and green energy need to drop out of the total amount of buying and selling in the economy, not replace and enhance it. My slogan is use less, share more. We actually need to distribute better and we can use less,. but they are all worried about offending the rich and powerful who’s votes they need and afraid of being less effective and thought of as a kook. Me, I just try to speak truth to power.

“Use less, share more.” What a wonderful slogan for the 21st century! Ethical, sustainable, and perhaps even—in many cases—politically powerful. It’s been bandied about a bit, but should really be coming on strong, starting in degrowth and steady-state circles.

Hi Brian. I ran myself into the ditch before I got to the end of the article because I got stuck on a couple of aspects of economics. Once I have a better understanding, I’ll call the tow truck and carry on.

In Ken’s ECON for Dummies course, I need to understand one basic notion. Assuming everyone received an even amount of $$ per unit time. Call it what you want: salary, basic universal income, still-breathing dividend. Doesn’t matter if you’re a CEO or Chief Sloth. You get the same amount.

Q: If everyone gets the same, does it matter if everyone gets $1, $10, or $100? To my way of thinking, it wouldn’t matter because prices would simply be altered by moving the decimal point accordingly.

If the answer is ‘no, it doesn’t matter’, which makes sense to me, then a couple of questions/observations arise:

1. Wealth is not an absolute measure but a comparative measure (except perhaps the emotional wealth of internal peace); the more one has COMPARED TO ONE’S NEIGHBOUR the wealthier one is.

2. If there was no race to have more than the next guy, would the GDP necessarily be steady?

3. If there is a race to have more, is there any hope of achieving steady state?

One last observation is that, to my lay eye, Steady State does not necessarily imply that everyone is paid the same through the course of their lives, even in the same job, and that difference occupations need receive the same remuneration. However, if we are to have inequality in current income, how does one avoid the desire to have more than the next person?

Not to mention determining remuneration rates for existing and novel occupation.

Would the attributes of a realized Steady State economy necessarily be defined in terms of the carrying capacity of the biosphere?

Take your time!

More seriously, I’m not expecting answers to these, I’m just pondering out loud.

Typos…

One last observation is that, to my lay eye, Steady State does not necessarily imply that everyone is paid the same through the course of their lives, even in the same job, and that different occupations need NOT receive the same remuneration. However, if we are to have inequality in current income, how does one avoid the desire to have more than the next person?

Not to mention determining remuneration rates for existing and novel occupation.

All this agonizing over growth versus steady state could be avoided if a basic income provided financial security in either case. However, basic incomers seem worryingly sanguine about growth. It will only work as it could and should if firmly tied to eco-taxes, and a recognition that an end to growth will happen by ghastly accident if we don’t plan for it. http://www.clivelord.wordpress.com

Thanks Brian for this thought-provoking piece!

Should degrowth be about bringing down GDP? My answer: not primarily.

GDP is just a blunt aggregate weighing scale. You can indeed make yourself sick by eating too much apple pie, but it also matters whether the pie contains too much dough and too few apples: a pie of the right size can still be unhealthy. Degrowth efforts are likely to bring down GDP because socially and ecologically undesirable economic activities that count towards GDP are deliberately replaced by socially and ecologically desirable economic activities that don’t count towards GDP. In other words, not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted. Other activities that currently count towards GDP, e.g., in health care, education, welfare and other public services, should be preserved—like apples in an apple pie. Degrowth is therefore not primarily about bringing down GDP; it’s about downscaling what is unhealthy, unfair and unsafe. GDP degrowth cannot guide us there.

Curious to hear your reaction!

There is some truth to that, but let’s consider a couple of metaphors:

1) You can only put so much lipstick on a pig. In this case the economy—super pig-sized now—has an inviolable trophic structure. To have all those healthy and happy services, we have to start with the agricultural/extractive surplus at the trophic base in order to free the hands for the division of labor unto said healthy services. GDP growth with healthy and happy services proliferating everywhere would still entail an expanding trophic base; i.e., expanding at the competitive exclusion of nonhuman species (and other aspects of biodiversity and environmental protection) in the aggregate.

2) In seafaring terms, when she’s loaded to the Plimsoll line it doesn’t matter if you add a puppy or a skunk; either way your ship is sunk! You can’t have a bajillion bicycles any more than you can a billion Hummers.

So, I believe we are left with recognizing the need for GDP degrowth for basic sustainability, as well as the efforts you note—efforts of the degrowth movement if you will—for a happier state of sustainability.

Thank you Brian for the great metaphors, and for taking time to respond. I agree with you that ‘healthy and happy’ services also contribute to throughput, and therefore to our ‘sinking ship’. But I’m still not 100% convinced about GDP degrowth, because it lumps together what should be downscaled and what should be preserved. Another metaphor: just as GDP growth is sailing by a wrong compass, so too could GDP degrowth lead us astray. So for me, we are left not with GDP degrowth, but with biophysical degrowth towards a steady-state (AND the ‘degrowth’ efforts I have noted).

Crelis, I am very tempted to say, acknowledging but the merest tinge of exaggeration, that there is nothing more biophysical than GDP! I say this due to a long-standing interest and investigation of the trophic structure of the human economy. See for example:

https://royalsoc.org.au/images/pdf/journal/152-1-Czech.pdf

This is pure ecological macroeconomics.

But of course, as I described in my book Supply Shock, the following must be accounted for when applying the trophic theory of money, perhaps in order of simplicity:

· Inflation

· Propensity to use money as the means of exchange

· International trade

· Technological progress

While technological progress may seem especially tricky to account for at first glance, it itself is tightly linked with GDP growth based upon current levels of technology. Economies of scale play a key role in this linkage. See here:

https://steadystate.org/wp-content/uploads/Czech_Technological_Progress.pdf

Thanks for the excellent references Brian.

The growth rates of GDP and material throughput are indeed very strongly correlated. No disagreement with you there. However, we are primarily concerned with lowering material throughput, not the indicator of GDP per se. Material throughput must shrink, which will undoubtedly bring down GDP. But we should not put the cart before the horse. For me, as a Degrowth scholar, the matter of how we shrink material throughput is key, and GDP-degrowth as a policy goal doesn’t help—especially as we begin to partly decommodify economic life, reclaim the commons and work towards other ambitions linked to the degrowth movement. I already referred to preserving (or even growing) essential basic services (more apples and less dough in the cake). Adding to that, it would be beneficial if the material standards of living of the ‘poor’ go up (on a side note: this type of growth is not equivalent to GDP growth in the global South, which tends to happen at the expense of the poor). In a world of limits, growth of throughput by the ‘under-consumers’ demands more degrowth of the throughput by the ‘over-consumers’.

These are just some examples of why we need more targeted degrowth strategies (as opposed to GDP-degrowth in the aggregate). Of course, in the aggregate, we also need to make sure that we downscale to and remain in a safe steady state. But I doubt that World GDP is the best indicator to help us make that assessment (especially if we start to transform the economy as mentioned above). To track our aggregate biophysical impacts, we might want to look at the planetary boundaries framework, for example.

Crelis, I don’t view the choice as either/or. I am all for targeted throughput caps, starting with oil at the wellhead and for several other resources at the lowest of trophic levels (where amplification is maximized). I also see throughput-lowering conservation regulations as economic policy writ environmentally. In the USA, for example, strict enforcement of the Endangered Species Act would lead to the steady state economy; albeit a steady state with many species eking out an existence on the barest limbs of the tree of life.

The main point of my article is that it is misleading and counterproductive to call for degrowth while wavering on the implications for GDP. When we cap oil at the wellhead, we will (ceteris paribus) be lowering the rate of GDP growth, ideally (for some time) into negative territory in wealthy regions. If we have conditioned our readers and public to think that GDP growth is “not necessarily” at stake, they will feel cheated and vote out the degrowth, wellhead-capping politicians in the very next cycle.

On the other side of that exact same coin, and as we’ll be demonstrating with the Full and Sustainable Employment Act—aka “Full Seas Act”—efforts to lower the rate of GDP growth (even into negative territory for some time, for accomplishing degrowth toward a steady state economy) will absolutely lower throughput. Take just three examples:

· Removing tax code incentives for having more children than two.

· Sectoral salary caps (see today’s Steady State Herald (later today)).

· Keeping the Federal Reserve (or whatever monetary authority) out of the growth game and purely onto its original mission of fighting inflation.

These and many other fiscal and monetary reforms are throughput droppers as surely as wellhead capping, and with crystal clarity of intent—vis-à-vis GDP—for all to see.

Thank you for this clarification Brian. I fully agree with you on the first point. It would indeed be counterproductive not to recognise that a reduction in throughput brings down GDP. I believe we are on the same page there. For me, the discussion was more about the second point, regarding the policy focus on GDP-degrowth.

There is a difference between saying “we need to reduce GDP” and “we need to understand that GDP will be reduced as a consequence of all this targeted degrowth stuff we‘ve been talking about.” It seems to me that the monetary/fiscal reforms you mentioned intend to do much more than to lower the indicator of GDP (even if that is going to be one of the outcomes). But maybe I am splitting hairs.

In any case, your article is in part about why some degrowthers are not engaging with a GDP-degrowth policy, or failing to take a clear stance. While I don’t speak for them of course, I was trying to provide examples of some of the ambitions in the degrowth movement for which GDP-degrowth doesn’t provide a very useful compass. At the same time, I do see the importance of debunking the GDP fetish. So of course it is not an either/or choice. We need to tackle the problem on many different fronts. But that is exactly the point I think; there are different fronts.

I’ve made many comments but

1) alot of these discussions are about terminology, which is important. (One another degrowth list people asked what term might be ‘best’ (as in most ‘saleable’ –some said degrowth, others steady state, or regenerative, etc.; i also like ‘Use Less , Share More’.

my own is ‘voluntary simplicity is another kind of complexity’.

I’m amazed since I listen to alot of mainstream media economists still talk about the need for ‘growth’ without ever discussing the issues with that (eg global warming), or what it means—most talk about reopening auto plants, pork palnts, and world trade… The media does report on GDP, its growth rate and the stock market, so maybe those terms and issues should just be abandoned —its mostly consumer culture and its ‘material footprint’ ( term in J Hickel’s and G Kallis’ 2019 paper on ‘green growth’).

2. My view is your ‘trophic theory of money’ is basically about the ‘material footprint’ (or throughput). To me its main important contribuition is to connect the ideas of economics, material footprint, etc to biology — others such as Yakovenko connect them to physics . e.g. https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.00111 (that is only one approach from physics). One reason ecological economics came about was because people seperated disciplines. ( the maximum entropy formalism used by Yakovenko or its nonequilibrium variants are also applied to biosystems— eariliest maybe was by E Kerner ( student of Feynman) , is now applied to biodiversity, genetics, etc.

I sort of agree with Hickel, Kallis and S. Pueyo that theoretically ‘green growth’ or ‘absolute decoupling’ is theoretically possible . The blog by Crelis on decoupling (april 26 2017) pretty much has my view. its ‘possible but unlikely. COVID lockdown showed alot of people didn’t have to drive 60 miles round trip in a traffic jam to work in an office. I’d subtract ‘commuting time’ from GDP.

I sort of went though that fairly dense paper a few times.

The idea that ‘agricultural surplus’ is essentially the origin of ‘trophic money’ reminds me of Marx’s labor theory of value. i.e. almost an ‘atomic or molecular decomposition’—just break up the atom or molecules into elements or fundamental particles, excepect in this case break up the modern world (technology, and everything else) into the agricultural plants at its source (corn, wheat, peas…) . Humans do eat the surplus and build the modern world but I dont think that explains the mechanism—it almost implies the world was always at equilibrium. i.e. the ground was there, and just transformed into agricultural surplus , and then into NYC etc.

As a semi-student of nonequilbrium thermodynamics (eg Ilya Prigogine I view as the most well known expositor of that—which is a few steps beyond Georges-Roegescu (sic?) ) in a sense that view could be true (it follows from Poincare’s recurrence theorem or paradox) but humans don’t see that. They see ‘progress’ or evolution , and transformation of ‘nothing’ (‘wasteland’ ) into ‘something’ (civilization or consumer culture).

One thing this view leaves out is ‘other resources’ (minerals,l, oil, etc.) — inputs into the human tropic level.

(The PNAS paper cited on ‘Eating up the world food web’ I think may be a more accurate seperation of organic sources for HTL (human trophic level) from other ones. one needs other nutrients at times to grow food.)

Also the conclusion that ‘finance has no effect on GDP’ seems to be an analog of Marx’s Labor Theory of Value (ie that the value of anything is how much labor went into it—as opposed to agricultural surplus. For Marx the fundamental particles of value or money was hours of work —didn’t really matter if you just moved around bricks or built a house .)

finance is used to fund oil exploration which affects GDP. . This is why you need a nonequilibrium perspective.

I totally agree with Crelis. only in this world is GDP correlated with material throughput. Also democracy in america was associated with slavery and genocide. that was unnecesary. .

these debates over degrowth, GDP, and steady states are confused—-tropic structure is not fixed but evolves just as does GDP.

Dear Brian Czech. I am so glad that you advance strongly rduce GDP when it needed. I give you 4 advices how to do it better:

1. Explain more that the Corona Pandemic is one of the conseqences of the ecological crisis, therefore another reason for a Steady State Economy. The Nature is saying: “OR YOU WILL STOP OVERCONSUMPTION OR I WILL STOP IT”.

https://www.cirad.fr/en/news/all-news-items/press-releases/2020/origins-epidemic-coronavirus

https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/science-points-causes-covid-19

2. Explain more that there is an ideal level of consumption and when you go from it to both sides it is bad for you not only because of the economy, security and environment. There are 3 times more people dying from Obesity than from Hunger. Millions of peoples die from overuse of artificial energy (Sedentary Lifestyle). The overuse of Screens (what means energy, matherials) create immence health problems. Overuse of artificial lights create Light Pollution and sound systems Noise Pollution that are very seriouse heath problems, etc.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Overconsumption#Effects_on_health

3. Explain more that the system of maximal growth had established not because it is better but because it create a higher military potential. It is just another reason for global peace.

4. Explain more that there is poor countries but not because there is not enough things. We need only to share justly. And this is not mean to those that have “Job” because the Jobs are commonly make money on nature destruction.

To clarify, Brian Czech’s online 2010 article in Resilience ‘the trophic theory of money’ (which overlaps with his writing here and in his books) I find to be clearer and i agree with alot of it.

I think one is arguing about definitions—same for ecological vs. environmental economics, degrowth vs steady state vs voluntary simplicity—i view these as all variants of similar ideas.

I sort of view GDP as the sum of the transactions in an economy —hence I like H Daly’s approach (the one i saw first) of defining ISEW (I call that GDP).

Its measured in units of ‘money’. .

It may be GDP is so associated with the standard things counted by Government agencies like BEA it should be scrapped (like some statues).

Chzeck’s ‘tropjhic theory’ emphasizes ;’material inputs and throughputs’–energy, minerals, water, land, etc.

I think introducing ‘trophic’ is a good idea—but its related to ideas like embodied energy, exergy, etc.

But my view is one should just monetize everything—monetize ‘natural capital’ and ‘ecosystems services’ ( Constanza, etc.) . Others have done amee for what used to be called ‘women’s work’ or unpaid housework such as childcare, house cleaning cooking, elder care, sick care. Some people pay for these so they go into GDP, other oeople just do them by themselves. The same for gardening, tutoring etc.

One could increase GDP immediatley just by counting ‘household work’.

Pollution (cleaning it up) .also goes into GDP but actually should be charged as a service–people have to pay people to pick up trash.

If people go ‘vegetarian’ they operate at a lower trophic level than carnivores. . Tourism (a hike in your local park) operates at as lower trophic level than a cruise.

Buildging a small home rather than a mansion is same–eg a log cabin. One can spend do ”arts’ or ‘learning science’. From the GDP=ISEW view you can be ‘richer’ without increasing energy use. I’d rather go for a hike than to NASCAR .

More rhetorical questions and observations:

1. Self-interest vs altruism in choice

Imagine there are only 4 individuals remaining of a species – say 2 male, 2 female gray whales, all frisky and fertile and ready to re-generate the species – and a person’s daughter is in the hospital facing a life-critical disease. There is a cure, but the cure means that all four remaining gray whales must be “harvested” (such a lovely euphemism) and, from their remains, the cure is extracted.

Now imagine the same choice faced all of humanity but with a different species being the saviour for each person. We would run out of species before we cured everyone. (Estimates are of <10 million species).

This speaks of how we perceive the value of a human life compared to that of other species but also how we are so interested in individual liberty without concern for cumulative impacts of all that liberty. (Obviously, looking at ongoing news soverage, it doesn’t speak to how we value human lives comparatively)

2. GDP degrowth does not necessarily correlate to environmental Kumbaya.

Looking at Europe’s forests, to pick one example. These were largely decimated before the turn of the 20th C and I think it fair to say that the GDP of Europe to that point was a lot smaller than it is today. A more general example is the human propensity to exploit a resource to extinction.

One might counter that, now, we are more informed and asking new and important questions. Perhaps, but we are still extracting resources to extinction, directly or indirectly, even as we discuss these new and important questions.

At the same time, however, if the “answer” is in the reduction of (let’s limit it to) virgin resource extraction, it certainly is useful to have an understanding of what might happen in our day-to-day existence (i.e. the economy) if we quickly were to reduce the available virgin resource capital. See my #4.

3. I am an advocate of immediately tossing GDP into the gutter but even ISEW, GPI, etc. have their issues. Chief among them is the notion of valuing ecosystem services; for example, what is the true cost of cutting down a redwood?

Though I realize that smarter and more educated people than I differ in this opinion, I think it’s a mug’s game, in my lay opinion, for this reason.

https://tinyurl.com/ybmlx59c

According to this item, it is estimated that only about 15% of the planet’s fauna and flora have been described, and, even in that 15%, we don’t know fully what each species extracts from and returns to the ecosystems in which they are found. For example, it was fairly recently that scientists discovered the important nutrient source that are salmon to the forests of the pacific northwest.

How can we possibly value ecosystem services – and use those numbers in calculations of GPI, ISEW, etc. – when we, honestly, don’t have a substantive grasp on what is happening in those ecosystems and what services even exist.

4. As in #1, I like to ponder rhetorical questions. Here’s another one.

Let’s assume that humans need do nothing to meet their basic needs – they extract all necessary nutrients from the air, and whatever personal waste they generate is diffused back into the air, they aren’t greedy and don’t need anything to enjoy life. They are never too hot, nor too cold. But, they do want to keep occupied. So, the “economy” consists of spending time thinking-up jokes and then gathering together to exchange jokes. Each person’s product is a joke. There is no resource input to manufacture the product nor any waste product from either production or consumption. The product is simply produced and consumed. I suppose some people might not be adept at stand-up and some might not be bothered to even try. So, how would that economy function? What would be a unit of exchange? Would people look at the teller of lousy jokes as less than equals? How would those who don’t tell jokes be viewed? Would people be labeled as free-loaders or would that concept not even exist? Would the stand-up stars expect some additional recognition over the poor comedians? What if they didn’t?

How much of what we see as human behaviour is truly necessary in our species? How much of our behaviour ultimately dooms us and all that is around us?

ken p. i like thought experiments. so, for degrowth first we simply eliminate all humans. the we look closely at floras and faunas to see they have an economy—plants amass photons and biomass, faunas get the plants . 2nd law still holds. unless they can recycle some suns from outer space.

Ishi C., I don’t understand your point here.

I would add that the tendency to use resources to exhaustion is not limited to humans. Other species appear to also require extra-special (As in SPEECE-ial; is that a word?) checks on their populations and behaviours.

For example: https://www.fws.gov/refuge/alaska_maritime/visit/hunting.html#:~:text=On%20the%20wilderness%20island%20of,(slow%2Dgrowing%20lichens).

In a “steady” natural economy (if such a thing exists), various forces, it seems to me, have, over time and through complex web of species interactions and resource inputs, fallen – as opposed to developed – into (more or less) equilibrium.

Until something – a meteor, a Henry Ford, Homo Sapien – occurs to disrupt the equilibrium at which point the natural order is tossed out the window. There IS a word for this progression/cycling of a system by I can’t remember it. (The book I am thinking of has a graphic of the infinity symbol on the cover).

Thank goodness I can see my book orders from 15 years ago.

“Panarchy” is the word I had in mind.

https://www.resalliance.org/panarchy