Building Upon the Trophic Theory of Money: Preliminary Results from Canada

By James Magnus-Johnston

The human economy doesn’t just mimic the economy of nature; it is part of it. It is woven directly into the ecological system of producers and consumers. Due to the technological prowess of Homo sapiens, though, the human presence dominates, threatening other species and the life support system of the planet. Human dominance over non-human life leads us to acknowledge some uncomfortable truths, particularly for proponents of “green growth.”

The first pertains to the loss of biodiversity. As the human economy grows, biodiversity must be sacrificed. The economy grows from the “bottom up,” starting with the agricultural and extractive activity that displaces non-human species. This is the essence of what Brian Czech calls the “trophic theory of money.”

In this anchored clip, Brian Czech defines the trophic theory of money in a 2018 presentation to the Royal Society of New South Wales.

The trophic theory of money changes the way we think about pathways toward a greener, sustainable society. For example, it makes us think twice about strategies for “green growth,” including the following two:

- Using sectors like tech and tourism to shift away from farming and extraction (“dematerialization”).

- Investing in a renewable energy strategy that shifts the economy away from fossil fuels.

While both strategies have merit, it’s important to consider the systemic material implications of each strategy: How does each relate to the agro/extractive base of the economy and biodiversity loss? What are their rebound effects?

An alternative warrant for a greener society would be to use the trophic theory of money as an overarching design constraint. Instead of attempting to “dematerialize” GDP, we can instead work toward social wellbeing at an appropriately scaled, non-growing GDP. We can, in other words, opt for a steady state economy at some relatively optimal level. Before we can expect widespread acceptance of this option, however, we’ll probably need wider-spread knowledge of trophic principles.

What is the “Trophic Structure” of the Economy?

It takes producers and production to support consumers and consumption. In any ecosystem, from local to planetary, primary consumers (like voles and rabbits) require producers (like grasses and forbs), while secondary consumers (like shrews and weasels) require primary consumers (like voles and rabbits). For an ecosystem to be sufficiently developed to host tertiary consumers (like bobcats and eagles), there must be plenty of production, primary consumption, and secondary consumption “below.”

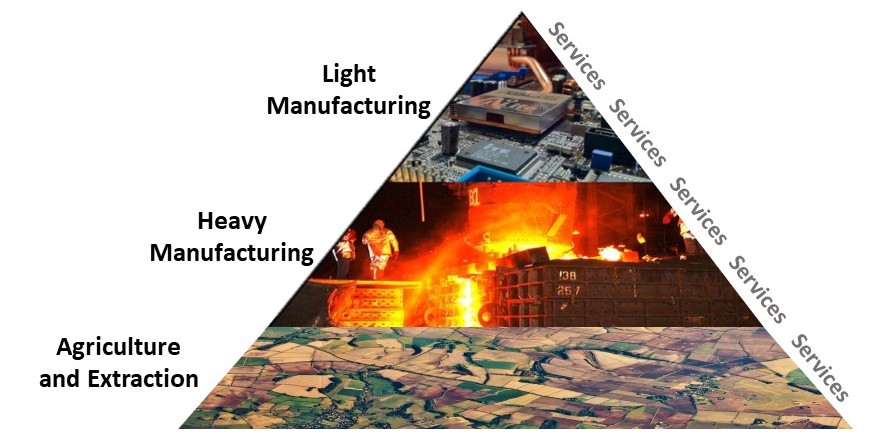

The trophic structure of the economy consists of producers, manufacturing sectors, and services. The corresponding trophic theory of money is that “money originates via the agricultural surplus that frees the hands for the division of labor unto manufacturing and service sectors.” In other words, the real economy is reflected by flows of real (inflation-adjusted) money.

These “trophic levels”—producers, primary consumers, secondary consumers, etc.—comprise the “trophic structure” of nature. “Trophic” simply refers to the flow of energy and material, or the “low-entropy flow” described by Herman Daly. Each time biomass (plant material or animal flesh) is consumed for the growth or maintenance of the consumer, waste is co-produced and energy is lost as heat. The certainty of waste follows from the second law of thermodynamics (that is, the entropy law).

In the human economy, manufacturing sectors build upon the agricultural and extractive base. Service sectors are not as readily assigned to particular levels in the trophic structure. Some service sectors—tourism for example—are best modeled as high trophic levels. Tourism doesn’t literally “serve” other sectors, but rather comprises a high level of consumption allowed for by surplus production starting at the trophic base. Other service sectors, though, are more appropriately modeled as interwoven throughout all trophic levels. For example, the transportation sector serves virtually all other sectors ranging from agricultural and extractive all the way through the manufacturing sectors and up to tourism and entertainment sectors.

Why is this trophic structure consequential? Because the clearly “material” sectors (agriculture, extraction, and manufacturing) are inseparable from the “immaterial” sectors (i.e., services such as insurance and finance). In fact, the material and immaterial sectors are mutually dependent, and ultimately the primary dependence is upon the agricultural and extractive sectors. Manufacturing and services would not exist without the agricultural and extractive base; more manufacturing and services require more agricultural and extractive surplus.

The money-material correlation might be less evident in national economies where services predominate, but that doesn’t mean the trophic dynamics don’t exist. For example, a Swiss investor might be earning revenue from resource extraction in Mali. What appears as “immaterial” financial sector revenue in Swiss accounting still has a large material footprint in Mali.

As resources are exchanged up the trophic pyramid, value is created and revenue is produced. In this way, value (represented by real money) becomes a unit of pressure on the environment. Every time a trophic conversion happens, it produces waste (material waste and waste heat) as well as a stream of revenue. The trophic theory of money suggests that the generation and flow of real money—namely the flow of expenditure contributing to GDP—is concurrently, concomitantly a measure of economic output and environmental impact (including especially biodiversity loss).

As Czech has pointed out, inflation, technological progress, and international trade can warp the tight linkage between GDP and environmental impact. But, as we hope to demonstrate with further research results, these phenomena do not affect the underlying trophic structure of the economy, nor do they refute the trophic theory of money.

Initial Research: Money-Material Correlation in Canada

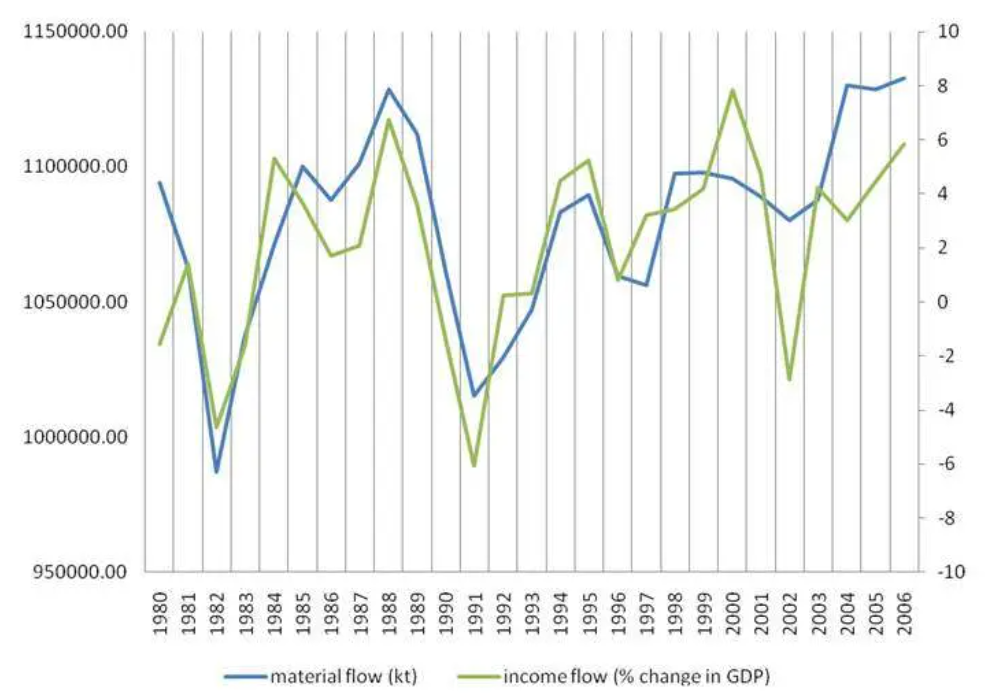

Almost fifteen years ago, without the benefit of numerous intervening studies, Herman Daly wrote, “ecological economics sees coupling [between income and environmental degradation] as by no means fixed, but not nearly as flexible as neoclassicals believe it to be—in other words, the ‘dematerialization’ of GNP and the ‘information economy’ will not save growth economics.”[i] I tested the idea in 2010 by comparing materials use with income (GDP) in the Canadian economy over a quarter-century. I found that the coupling of aggregate materials and aggregate inflation-adjusted income in Canada is indeed pretty tight. I called this coupling the “money-material correlation.”

Money-Material Correlation in Canada, 1980-2006

In the first phase of the study—the phase producing the figure above—I considered materials use (material flow or MFA); later I also considered the ecological footprint. I wanted a metric that would concretize the idea of material growth (that is, resource use), and MFA fit the bill. I also wanted to understand the general environmental impact of GDP growth, and looked to the ecological footprint for a general understanding. In both the MFA and ecological footprint studies, as one might expect, the correlation with GDP was tight.

My study was, in fact, a test of the trophic theory of money. The results were promising. That said, further testing is probably required before we can establish GDP as a widely accepted indicator of environmental impact.

Future Testing

The trophic theory of money would seem to set design constraints for the pursuit of a greener society, whether as a shift toward tech/tourism, or toward “green” energy. Pursuant to the trophic theory, the economy cannot be “dematerialized” by substituting agro-extractive activities with services like tourism or tech. While the notion of dematerialization has largely been debunked in ecological economics, it remains a popular idea in neoclassical economics and political circles. Further evidence corroborating the trophic theory of money could be the nail in the coffin for dematerialization and “green growth.”

The second argument to consider through the lens of trophic theory is whether or not energy sources are substitutable. The answer will have implications for where we should invest our time and money in the effort to build a better world. The trophic model helps us to recognize that the raw materials required for all energy systems need fossil energy: first to extract; and then to produce and maintain. Fossil energy, as explored in depth by Vaclav Smil and others, is not always substitutable. Fundamentally, whether referring to hydro, nuclear, solar, or wind, each of these energy sources requires oil and other raw materials to build and maintain, in addition to the metabolic and transportation needs of the human beings who design and maintain the systems.

Whether referring to economic sector substitution or energy substitution, the general design principle in operation here is similar: We must consider the metabolic needs of the system and the full spectrum of land and energy inputs. By evaluating the economy as a complete system, we can determine the raw inputs and fossil energy requirements of services or renewables in the trophic structure. More importantly, as resources “climb” up the trophic levels and material conversions take place, the resulting revenue streams are likely to signal biodiversity loss (and other aspects of environmental impact) as much as income gain.

To test the trophic theory of money, then, I intend to reproduce the money-material correlation in other jurisdictions with diverse economies and widespread agro-extractive activities, including China, the USA, and Russia. If there proves to be a strong link between GDP and various indicators of environmental impact under such differing models of political economy, it would be wise for us to include the trophic theory of money as a central feature of ecological macroeconomics, as well as economic policy for the 21st century.

[i] Daly, H. 2007. Ecological Economics and Sustainable Development. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, U.K. See page 88.

James Magnus-Johnston is a PhD researcher at McGill University in the Leadership for the Ecozoic program.

James Magnus-Johnston is a PhD researcher at McGill University in the Leadership for the Ecozoic program.

Please tighten specifying units. I infer that the graph displays material flow measured in kt/yr and % change in GDP measured in $/yr/yr. Decoupling has consistently has referred to flow vs. flow, e.g., energy/yr vs $/yr. So the units in the graph indicate a stock-flow mismatch. Please clarify.

Hi Robert. I would argue that this is still a flow-flow comparison, albeit a different one than the kind you cite. Kt/yr refers to the flow of domestic extraction: “all biotic and abiotic raw materials that are extracted from the domestic environment and further used in production processes.” If I understand your point re: money, a % change in GDP is still measuring flow. Income itself (GDP) is a flow unit (ie. rather than a measurement of a money “stock”). Perhaps we could chat further about this face-to-face?

I concur with the basic premise of the tropic theory of money, though I look forward to seeing further research and analysis to support it. I question the assertion about the substitutability of other energy sources for fossil fuels, though I have not read Smil’s monograph. Not all wastes are created equal and carbon emissions threaten the ecosphere in even more drastic ways than other forms of human waste. As in the general case of “zero waste,” operationally defined as 90% diversion of materials from landfills, there’s a long, long way to go before we have to confront the ultimate thermodynamic limits. The “circular economy” will never totally dematerialize society. but we can do very much better than presently. We likely will have to develop economical CO2 removal technologies, but first we must reduce emissions. There’s much to do while building the case for a steady state economy.

I’m not an abstract thinker but from this article I was able to understand how “the economy cannot be “dematerialized” by substituting agro-extractive activities with services like tourism or tech”. But I have trouble understanding how economic sectors like tourism and agriculture can be quantified, given they are so varied from within. Certainly the cruise industry is not in the category as bicycle touring which uses human energy. Or agriculture: I once did subsistence agriculture and I felt nothing in common, energywise or in relation to GDP, with a soy or hog producer. Perhaps yours is strictly ecological macro economics, but for a degrowth economic policy for the 21st century, it would seem that micro alternatives should play a primary role. I am not an economist so forgive me if I frustrate the reader with naive pronouncements.

The idea that money originates as a matter of agricultural surplus is not accurate. And the notion that GDP reflects this surplus is inconsistent.

Not only agriculture but also manufacture, industrial and service can be produced for others and has formed along the centuries a growing and complex economic activity.

And, GDP reflects (with a lot of deficiencies) goods and services created in a given period and thus is a direct consequence of labor employed in the process. As well known and obvious, labor is the only way to create wealth.