Introducing the Sustainable Population and Immigration Act

by Brian Czech

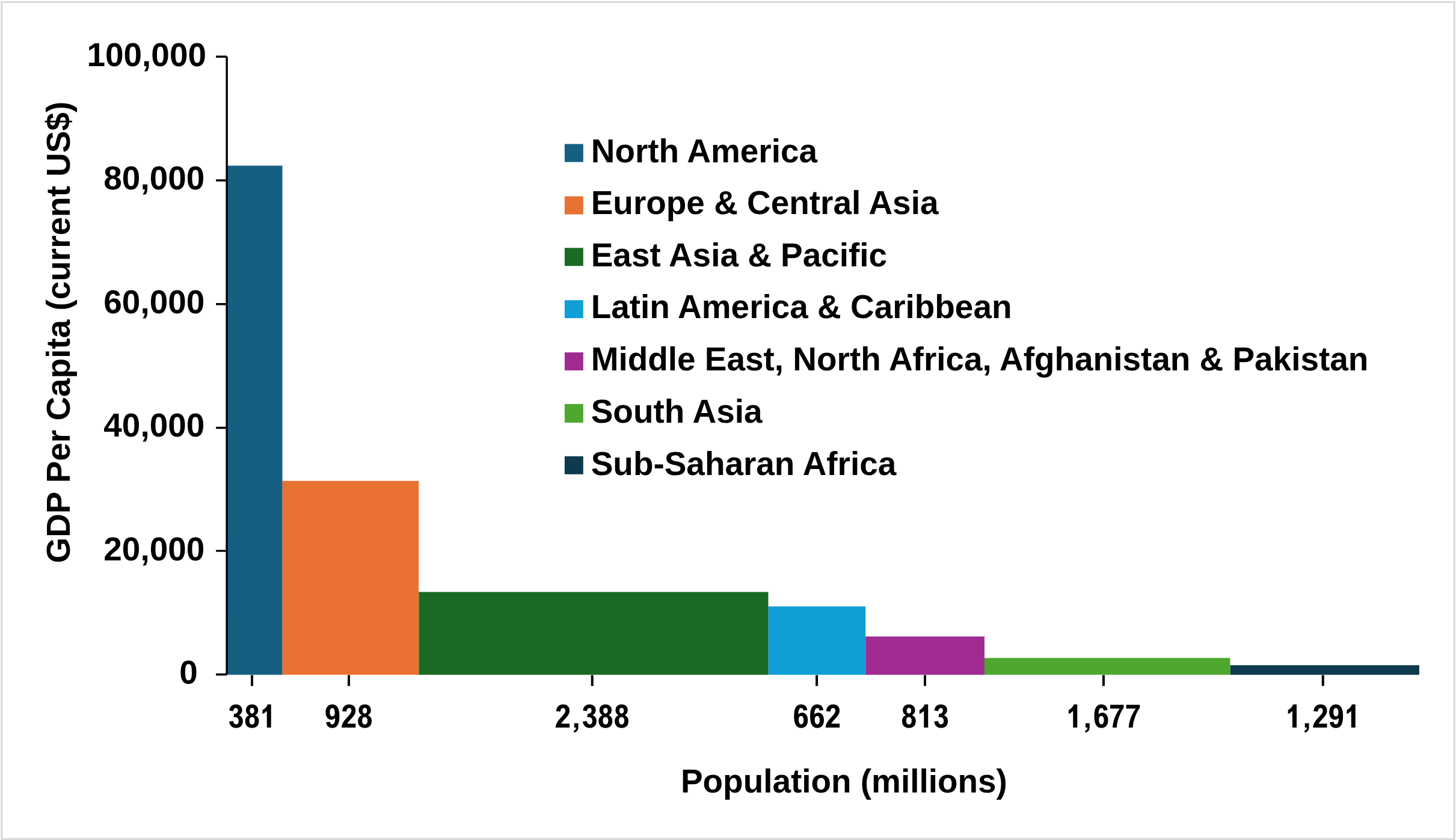

Population and per capita consumption of geopolitical regions in 2024. The area (length × width) of a bar, then, indicates GDP, and therefore ecological footprint. Bars display the relative importance of population vs. per capita consumption among regions. (CASSE, data from the World Bank)

A steady state economy requires, by definition, a stabilized population. If population is not stabilized, it won’t matter how much we try to conserve. Our consumption as individuals—“per capita consumption”—can only go so low before we hit the lower limits of mere survival.

Mere survival isn’t comfortable, much less fun. It precludes any political viability for keeping consumption at minimal levels. So, as a society concerned about sustainability, we strive for a reasonable level of consumption that provides wellbeing without exceeding ecological capacity.

That’s why writers like me have focused on per capita consumption for decades. But at some point, population must be dealt with, too, as it will be herein. A key consideration is where to apply this population focus in public policy.

Think Globally, Act Nationally

Ideally, population policy would be applied at the global level. Theoretically, that could alleviate the unsustainable migration pressures as well as internal growth in regions where native fertility rates are too high. The problem is, public policy entails governance, and there is no global government. Also, who are we (“we” meaning citizens of any nation) to tell people halfway around the world what to do in their own environs?

No, population policy is a matter for nation states. When a nation develops a steady-state population policy, it can then engage in demographic diplomacy. Such diplomacy may manifest directly with other nations and in pseudo-governmental institutions of regional and global scope, the most comprehensive being the UN General Assembly. The European Union, African Union, World Health Organization, and World Bank are some of the other key institutions.

United Nations General Assembly, New York, where steady statesmanship and demographic diplomacy are in dire need. Which nation will set the precedent? (CC BY-SA 3.0, Basil D Soufi)

At this point in history, population policy seems most promising if it starts in a relatively democratic nation with precedent-setting power. This nation would need the fiscal means to transition to a steady state economy without precipitating a political backlash.

To grasp the merits of this perspective, first imagine the leadership of a poverty-stricken nation announcing to its impoverished citizens that, in order to protect the environment, it was time to stop growing the GDP. That wouldn’t fly, and it shouldn’t. Poor countries still need GDP growth, as described in the foremost online position on economic growth.

And don’t forget, in most countries economists would be advising that population growth was required for GDP growth. In fact, they would prescribing—shockingly to the uninitiated—population growth for increasing not only GDP, but GDP per capita! That’s right; they have rationalized that, because a larger population should have a larger cohort devoted to research and development (begetting technological progress) a higher density of people results in more goods and services per person.

Due to slow-changing cultural reasons, too, we cannot expect many nations with widespread poverty—even if stereotyped as “overpopulated”—to lead the world in population stabilization, much less reduction.

Rather, the precedent-setting nation will need an economy fat enough for trimming without considerably impacting the consumption habits of the majority. This is especially the case because there will be a transition period in which population will still be growing as the nation attempts to stabilize its GDP (and therefore its ecological footprint). That means per capita consumption will decline, making it politically essential to stabilize population (and therefore GDP/capita) before the belt-tightening hits the majority too hard.

For purposes of precedent, the nation should also be large and strong, not likely to be ignored or geopolitically bullied. Population size is determined by immigration and emigration (along with births and deaths), so the precedent-setting country must be fully capable of maintaining its borders.

Finally, the country will also need a sense of its own limits to growth. Until then, it won’t have the wherewithal to stabilize population or consumption.

A Steady State of America

In my opinion, the nation that best fits the precedent-setter criteria laid out above is the United States. While American democracy is ailing, it still operates pursuant to the basic principles of democracy laid out in the Constitution and fleshed out in statutory and case law. The United States is also one of the wealthiest countries in the world. It is notorious for conspicuous consumption but famous also for a history of conservation ethics, environmental movements, and ecological economics.

For a steady state of America, the stars of the show are population and per capita consumption. Ideally the multiplied product, GDP, is in the optimal zone: not too sparse and not too crowded (with people and stuff). (flag: Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons; stars panel modified by CASSE)

I want the United States to set the precedent of stabilizing its population intentionally, ethically, and durably, without the 20thcentury draconian measures practiced in India, Peru, and most notably in Deng Xiaoping’s China. Sadly, recent raids of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency have been ruthless and not even designed for stabilizing population, but rather coupled with a president’s obsession with GDP growth.

Morally decrepit population management is not only wrong in a normative sense; it won’t stand a test of time, either. The U.S. should develop a population stabilization policy based on sound science and lengthy dialog about limits to growth and the need for a steady state economy.

Indeed, it has been over five decades since the United States published the 1972 President’s Report on Population, culminating the advisory work of the Commission on Population Growth and the American Future under President Nixon. The Population Bomb (1968) and Limits to Growth (1972) were bestsellers. President Carter commissioned the Global 2000 Report to the President (1980), which echoed the 1972 report, but with a greater emphasis on global population.

The tide turned, though, when Ronald Reagan took over the White House in 1981. He explicitly disregarded the limits to growth. His aggressively pro-growth, supply-side economics established a foothold in politics and policy, aided and abetted by neoclassical growth theory and the fallacious notion of perpetual population and GDP growth. Dialog on stabilizing population has since been muffled.

Muffled, but not extinguished. In my opinion, there is tremendous latent concern about “too many people” among the American public. If there wasn’t, the immigration reform movement wouldn’t be nearly as loud and influential. Critics of open borders include racist and nationalist extremists—bad and ugly—but they also include many good people who simply don’t like the pace of change, especially in our rural and exurban regions. I suspect these Americans number in the tens of millions.

In other words, the more genuine desire to “make” America great “again” is not so much about skin color, foreign languages, and different garb, but rather about too many stop signs, too much competition for jobs, and too many children for the schools to handle. It’s about limits to growth: population growth and economic growth. We need to keep America great by stabilizing population, consumption, and GDP. That’s how we maintain our ecological capacity for health and happiness.

Introducing the Sustainable Population and Immigration Act

The Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy has been constructing a Steady State Economy Act for over five years and producing “feeder bills” on a monthly basis since early 2024. Some of the feeder bills—Salary Cap Act for example—should be politically feasible with or without the goal of a steady state economy.

Others, though, such as the Sustainable Budgets Act, won’t be feasible any time soon; not until the United States has truly reckoned with limits to growth.

Guess which category the freshly minted Sustainable Population and Immigration Act falls into? That’s right: Such a bill has as much of a chance on today’s Capitol Hill as a polar bear has (anywhere) in the year 2500. But it’s worth putting these feeder bills out in bite-sized portions, so readers can digest the omnibus bill over time and develop a sense of steady statesmanship in domestic policy.

Furthermore, I believe a majority of Americans (not the capitalist cronies on Capitol Hill) would be in favor of SPIA, if only they had the benefit of a town hall or two on the topic. Certainly elements of the bill already resonate with large swaths of the American public.

That said, please note a disclaimer while considering the merits of the bill: SPIA advocates, starting with myself, are not calling for an end to all immigration; not now and probably ever. In fact, SPIA advocates are lukewarm about any tightening of U.S. borders prior to a concerted effort to achieve a steady state economy. (Borderland law enforcement to address violent crime is crucial at all times, of course.)

Rather, SPIA is predicated on a political timeframe in which the steady state economy has been formally adopted as a policy goal of the United States. Keep in mind, the plan is for SPIA to comprise a section (Section 7, tentatively) of the omnibus Steady State Economy Act. As such, there is no way for its prescriptive measures to take effect unless and until the nation has indeed decided to embark upon steady statesmanship.

As a feeder bill, SPIA comprises seven sections. Section 1, as usual, is used to provide the short title: Sustainable Population and Immigration Act. (The full title is “A bill to establish the principles and practices for maintaining a stabilized, sustainable population, including sustainable levels of immigration, in the United States.”)

As a feeder bill, SPIA comprises seven sections. Section 1, as usual, is used to provide the short title: Sustainable Population and Immigration Act. (The full title is “A bill to establish the principles and practices for maintaining a stabilized, sustainable population, including sustainable levels of immigration, in the United States.”)

Section 2 is in many ways the most critical component. It comprises the findings and declarations of Congress, in which Congress expresses its paradigm shift from the goal of economic growth to the goal of a steady state economy. In short order, Congress finds that stabilizing population is an essential aspect of a steady state economy. Congress then declares that (among other things) it is the policy of the United States to “allow for immigration levels, that, considering fertility, mortality, and emigration rates, result in a stabilized U.S. population.”

Section 3 provides definitions. I’ve taken the liberty to simplify the onerous terminology related to immigration, as manifest in the maze of visa categories. In the process, I invented a few terms, perhaps the most important of which is “steady-state net migration,” which entails immigration levels that countervail low fertility rates, resulting in a stabilized population.

To clarify, I am not criticizing the current catalog of visa categories maintained by the U.S. Department of State. Each category exists for a reason. But for our purposes—and for Congress’s purposes with SPIA—numerous categories can be rolled up into higher-level taxa such as “immigrant visas.”

The beauty and joy of human diversity. Unfortunately, not all faces are smiling as the limits to growth are approached. (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, Julie Kertesz)

Speaking of the State Department, the Secretary thereof is the primary agent of SPIA, along with the Commission on Economic Sustainability (a Steady State Economy Act construct). Pursuant to SPIA’s Section 4, the Commission serves as the clearinghouse for population data (drawing heavily from the U.S. Census Bureau) and the calculator of a “gross immigration allowance.” The allowance is prescribed in gradualist fashion to achieve steady-state net migration over a 25-year transition period.

Section 6 establishes the Aid-in-Place Fund, a concept percolating since 2022. The funding was envisioned to aid “the same number of people that otherwise would have legally emigrated to the USA.” The aid “would take the form of housing, health care, schooling, job training, and other living standards on a case-by-case basis.” Section 6 lays out criteria for Aid-in-Place funding including, for example, absolute poverty, emigration rates, and reproductive rights of women.

Section 7 ensures that SPIA comports with the Sustainable Budgets Act (a key component of fiscal policy in the omnibus Steady State Economy Act). A principle of sustainable, steady-state budgeting is no net gain in bureaucracy, or at least in government spending. SPIA expenses are insignificant, with the exception of the Aid-in-Place Fund. Therefore, Aid-in-Place funding is offset by concurrent reductions in Department of Defense spending.

What’s Left Out

No act of Congress can solve all problems. SPIA won’t even solve all the problems of population stabilization and immigration, much less naturalization, asylum, and family reunification. It is concerned almost entirely with stabilizing the American population, conducive to a steady state economy.

In the textbook terms of ecological economics, then, SPIA is concerned with the goal of “sustainable scale,” not so much with an equitable distribution of wealth or the efficient allocation of resources. It is focused on sustainability, yet in a way that social justice is improved (far from fulfilled) via Aid-in-Place.

Numerous other issues should be included in a comprehensive population policy. For starters, as CASSE Senior Economist Dave Shreve has proffered:

- Certain U.S. states should be funded for purposes of immigration enforcement and naturalization.

- Immigration routes should be far better established for purposes of safety and efficiency (of travel as well as enforcement).

- World Bank and United Nations programs need re-tooling toward population stabilization, especially via family planning and women’s reproductive rights.

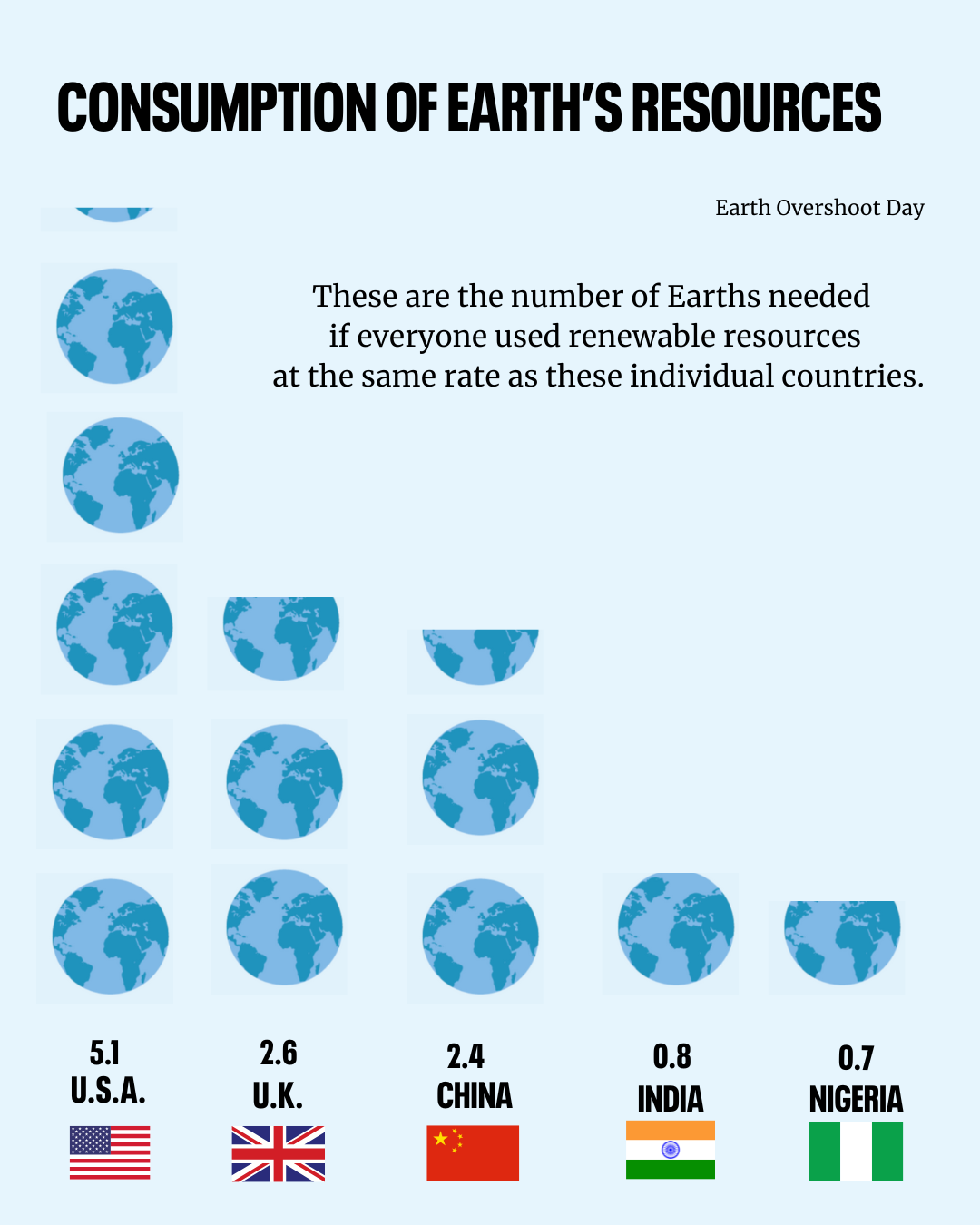

Crucial as it is, stabilizing population isn’t enough for establishing a steady state economy. Not when per capita consumption is beyond the sustainable threshold. Therefore, both are addressed in the Steady State Economy Act. (Figure originally published in Re-Wild Magazine Winter Edition (2025), 2024 data from Earth Overshoot Day.)

To be clear, even the sustainability element is hardly perfected in SPIA. The SPIA focus on stabilizing population won’t satisfy those who assess the U.S. population as already higher than long-term carrying capacity. That said, SPIA does accommodate the prospects of population degrowth, depending on the reports and prescriptions of the Commission on Economic Sustainability.

With SPIA, the Steady State Economy Act is approaching 75% completion. When all the feeder bills are published, the process of rolling them up into the omnibus bill may begin. That process will surely include numerous amendments, especially additions, to address issues like the ones noted above. A primary source of amendatory issues and language will be the comments provided by Herald readers.

So, if you feel strongly about SPIA revision, now is the ideal time to register your concerns!

Brian Czech is Executive Director of CASSE.

Brian Czech is Executive Director of CASSE.

Hello Brian,

Glad to see you carefully wading into the immigration discussion. There are some good aspects to your proposed bill; above all, the ideas of making population policy consciously, and not doing so as subservient to mainstream economic goals.

However, I doubt anything like 340 million Americans is sustainable under any per capita consumption/production levels we are likely to achieve. That calls into question your focus on creating a stable population. What we should be proposing are measures to gradually and non-coercively decrease our population.

With the U.S. TFR around 1.6 and support high for reducing current immigration levels, we could actually be only a few years away from beginning to decrease the U.S. population. That’s a goal sustainability advocates should embrace. To do so, we should support current legislation before Congress, such as the Nuclear Family Priority Act (H.R. 2705 / S. 1328), which would decrease current immigration levels.

Finally, I don’t understand your position that we should wait to address population matters until the U.S. fully commits to a steady-state economy. Those of us who care about sustainability don’t have the luxury of turning up our noses at the one area where we seem to be making progress — slowing population growth — and where there is considerable support across the political spectrum for doing so.

Across the developed world, fertility rates are low and support for continuing mass immigration is lower. We should take advantage of these trends to achieve one key component of a steady-state economy — an end to population growth — and begin the journey toward real sustainability by reversing it.

From my perspective, steady-state logic points toward population distribution based on biocapacity. I’m not implying this should be enforced, but that no country should shut down its borders under the banner of steady statesmanship until it’s reached this threshold: population proportionate to biocapacity.

According to my back-of-the-envelope calculations using Global Footprint Network data, the US has 9-10% of the world’s biocapacity. By the above logic, we should be prepared to accommodate 9-10% of the world’s population: ~800M. I’m from the Midwest, and I find this number just as eye-watering as many US readers would. But from a global perspective, I don’t believe shutting our borders before we’ve reached this proportionate threshold is just.

This is especially true when one considers that our excessive economy is largely responsible for the conditions prompting people to leave their homes and seek a better life. This argument is clear when it comes to climate change, but it can also be made regarding multinational corporations (land grabs, pollution, low wages), the military-industrial complex (fueling conflict), and the debt infrastructure that causes low-income countries to spend their resources on paying back interest instead of on social welfare.

800M people consuming like Americans would be ecologically devastating. But “keep them out so they don’t consume as much as us” doesn’t sit well. The fact that 800M is not an ideal population for the US should add urgency to the goals of:

1) decreasing US consumption per capita, starting with the wealthiest (the other Steady State Economy Act bills are designed for this);

2) advocating for women’s empowerment, sex ed, access to contraceptives, etc., around the world—if the global population declines, so does that proportionate-to-biocapacity number; and

3) getting smarter and better at accommodating immigrants, including fostering a sense of global community via informational campaigns.

To clarify, SPIA could be compatible with my logic, depending on when and under what conditions the 25-year transition period begins. In this sense, my comment is the opposite of Mr. Cafaro’s (which I respect). Mr. Cafaro says, “Why not start now?” and I say, “Too soon for this.”

While “population distribution based on biocapacity” appears as a reasonable guideline, “biocapacity” is such an elastic concept (variable depending on premises and objectives) that it may not be very helpful or even misleading. I suggest it’s more straightforward to start from the distribution of people as it exists today and work towards stabilization and decline everywhere. Japan is already experiencing it. I think Bryan is right that the USA is the obvious next candidate to go that path. If not for the recent migrations into Western Europe, it would be well on its way to decline as well.

I appreciate, in Bryan’s essay, the attention to nuance and its deliberate limitation of scope ( the list of things the proposed Act does *not* do).

Alix (continued): I preferred Australia when it had 15 million people. I also believe that the additional benefits of population growth in Australia, which is largely driven by large immigration numbers, have long been exceeded by the additional costs. Population growth is now ‘uneconomic’.

A country should be able to determine its own population numbers and not be pressured to increase its population simply because the world’s population is rising. Australia’s per capita consumption is far too high, and it needs to reduce it. Many countries are absurdly overpopulated (e.g., China and India), and they need to do something to quell population growth. It’s not Australia’s duty to accept more people simply because the world is overpopulated. Its only obligation is to accept people in need (e.g., refugees), not people who would like to live in Australia because it has a more amenable climate, which often is the case.

Sorry, I have to disagree with you Alix. It is perhaps reasonable for a country that possesses 9-10% of the world’s biocapacity to accommodate 9-10% of the world’s population. But not if the world is overpopulated (which it is); the world’s population is rising; and the country in question has moved to ZPG in attempt to both reduce the impact of population growth on its own natural environment and to contribute to global ZPG. What you are suggesting takes population policy away from individual countries and renders it a hostage to global population growth. You are effectively asking countries to be equally overpopulated.

Australia is the same size as the 48 contiguous states as the USA and has a population of 27 million. It has a much smaller biocapacity owing to huge expanses of arid and semi-arid regions. I personally believe Australia, which has a very fragile natural environment, is overpopulated. Australia’s population growth rate is one of the highest in the Western World and its population has doubled in the past 50 years. We now have four grossly congested state capital cities (Australia only has six states and two territories) and population growth is affecting Australia’s wellbeing and contributing to a housing affordability crisis.

Thanks for this well-thought-out reply, Philip (and Erwin). I empathize with your position, which I think stems from an understanding of ownership and rights that is different from my own. I’ve spent a lot of time abroad (lived in a subsistence farming community in Panama for two years) and studied global affairs, so my perspective is global: We’re all on the same sinking boat, some of us are far more responsible than others for the sinking, and we need to distribute resources equitably amongst all in the boat.

I don’t see the US’s natural environment as “my own.” My country’s corporations–fueling my excessive consumption–haven’t seen other countries’ natural resources as their own. We’ve rendered the world hostage to our economic growth, which is usually a driver (if you dig enough layers deep) of emigration to the US.

We need to stop blatantly disregarding sovereignty when it comes to extraction before we can claim sovereignty as a reason to keep people out. And I don’t blame individual immigrants for their governments’ population policies. I’m not a population expert, but I think the biggest driver of birth-rate decline is income. If all we cared about was population (not consumption), one could conclude that getting as many people as possible into high-income countries was the ticket to reducing population.

It’s also worth noting, in the context of ownership and rights, that I (and I’m willing to guess you) am a descendent of immigrants.

Australia’s natural environment is not ‘my own’, but equally the world is not for everyone else to overpopulate and expect Australia to do likewise and share in global overpopulation.

There was a time when the world was a community of tightly held communities bound by international treaties and obligations. It no longer is, largely due to the change in the nature of the former Bretton Woods institutions (and the global geo-political situation), which has created a world economy organised around ‘globalisation’; the free and easy movement of capital and people; and global production location choice and subsequent trade according to the principle of ‘absolute advantage’ instead of ‘comparative advantage’.

The nation state exists for a good reason. It ought to exist as a means by which a national community can democratically introduce laws and policies to serve community purposes. Domestic population growth and being expected to share in global overpopulation undermines that. Almost every problem we have in Australia has population growth at its core – urban sprawl, loss of agricultural land and wildlife habitat, welfare-reducing urban consolidation and congestion (to combat urban sprawl), and uneconomic GDP growth. I’m sure the same can be said for many countries.

Continued: Yes, I’m a descent of immigrants. I was adopted as a baby and only found out in recent years that I’m a descendant of two First Fleet convicts (and one Second Fleet convict), which is the American equivalent of being a descendant of Pilgrim settlers on the Mayflower. Being opposed to large scale immigration is not ant-immigrant. Immigration is a policy and immigrants are people. Restricting immigration reduces the intake of people regardless of their skin colour, creed, or religion. It means fewer whites as well as fewer non-whites.

I believe that all countries, as a member of a community of countries, have an obligation to control their population numbers, just like they have an obligation to limit their per capita consumption, GHG emissions, etc. They have no obligation to share in ecologically destructive overpopulation.

Continued: Nothing would induce countries to do something about their excessive population than closing the door, to some extent, to emigration. Why do something about overpopulation when other countries will accept your surplus people, and in particular, if countries are obligated to accept them?

The demographic transition is a flawed way to deal with overpopulation. It is a reliance on one thing that is trashing the planet (excessive consumption – i.e., a rise in per capita GDP) to combat another factor trashing the planet. It is very laissez faire and avoids the use of command and control, which is the only way to deal with growth beyond carrying capacity. Command and control – mutually agreed upon mutual coercion (caps) – is at the forefront of cap-auction-trade policies, which should be applied to reproduction as well as resource extraction and waste generation.

Per capita Gross World product has doubled in the past fifty years. So has global population. How long do we have to wait for the demographic transition to bring global population growth to a halt? By the time it does, there will be too many people on Earth (there already are) consuming too much stuff (we already are).

Alix, Philip, thanks for this thoughtful discussion. The good news is that demographic transition theory has been challenged by some compelling recent research by Götmark and Andersson (2022), which shows that fertility rates fall not in response to economic development, but in response to the availability of contraceptives and the ability of women to use them. This is true across rich and poor countries, industrialized and not. The study is here, in case you’d like to take a look. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/sd.2470 It suggests that restoration of robust funding of international family planning programs, as existed in the 1970s and 80s, would be a powerful policy for any country interested in advancing a global steady state economy.

I appreciate Brian’s article for getting into nuances on a subject that I struggle with. Perhaps certain countries where there is an unintended population decline could provide us with lessons. I am thinking of Japan, for example. Second, politically, I would ask how people with a low carbon footprint would react when people with obscene ecological footprints, Bill Gates, for example, might be determining population policy. The richest 1% account for more carbon emissions than the poorest 66%. I imagine that a consensus for reducing population can only be achieved when inequality, within nations, is seriously addressed. Consider the image of Jeff Bezos’ hyper-emitting, grossly polluting wedding in a city, Venice, that might be the first to disappear with climate change.

An interesting idea but I am curious as to where from arises the notion that humanity, or any subset thereof numbering more than a few hundred persons, is capable of collectively acting, over the long run, in a manner that leaves any hope that a steady state economy is a possibility in the absence of might backed coercion. Even with the tool of force expertly and nobly wielded I expect that humanity as a whole is a out of its league on this topic. While we occasionally manage to come together in significant numbers to overcome immediate temporary threats to survival, there is nothing that I have read of our history or experienced in my 60 plus years circling the sun that remotely supports the idea that as a group we have the capacity to attain such a laudable goal. It seems to me that the evolutionary baggage we all carry that leads us to prioritize the now over the later and to judge our fortune only in comparison to our neighbour, even when we are well cared for in the now, raises an insurmountable obstacle here. I would be delighted to be convinced otherwise but any attempts to do so thus far have revealed a breathtaking naïveté regarding human collective behaviour. All signs seem to me to point to the sad fact that the masses truly is an ignorant beast incapable of learning from its past mistakes and that the future holds for us only an inevitable catastrophic collapse of civilization. Hopefully there will be enough (but not too many) of us left that are willing and able to prioritize reason over instinct after the next big fall to allow another kick at the can but I won’t hold my breath on that one. I will try to do what I can to help prove myself wrong. Unfortunately, I am only human.

Hi Arthur,

I understand your pessimism. I have come to the sober conclusion that a transition to a steady-state economy along with a steady-state/biocapacity human population will need an historical process, rather than a mere political one. It can’t be forced or legislated into existence if it’s going to be a stable and sustainable change. That said, what we can do, and this is difficult, is to work at the local level to help people realize their own capacity to produce and provide wealth for themselves working together instead of relying on the mega-for profit market system. We need to think small, not big; not more sophisticated technology, not power-over politics. But to help people come together in community. Money does not produce wealth, people do. This can be readily demonstrated. But, it requires sustained effort and commitment to help reawaken human beings to their need for one another and to be for one another. Richard Heinberg once wrote that the best thing we can do is “get know our neighbor”.

All I can add: if one can just think long term, let’s say 150 years, the need for an SPIA becomes clear. It’s just math.

A policy of ‘Nil Net Migration’ would be helpful ie same number allowed permanently in as those permanently leaving

Kudos to Brian Czech for taking the long view on this important policy matter. Taking the long-term view does imply, of course, that when our per capita consumption multiplied by our population finally places our ecological footprint within the earth’s bio-capacity, the product can and should be stabilized. But diminishing opportunities for ecological efficiency combined with a commitment to avoid diminishing our “quality of life,” present opportunity for change that alone may be insufficient. If we assume that faulty paradigms about the distribution of income and wealth also stand in the way, this is critical. It may not be possible at all, therefore—in thirty years’ time or a hundred—to reach a sustainable steady state without first encouraging population reduction. Because CASSE insists on reproductive freedom, direct legislative efforts in this are difficult. But we are in the middle of a fertility transition that is delivering population reduction—without coercion. Women on every continent have responded consistently to the factors that matter: reduced inequality, broadened economic and educational opportunity, the protection of reproductive autonomy, and ready access to family planning services. The gathering momentum of this change promises a surprisingly rapid transition. It merits increased support, where possible with legislation and forceful diplomacy. Those who resist it on the grounds of a bankrupt growth-first paradigm—still powerful and far too numerous—should be opposed with equal vigor.

Population control policy is going to meet with intense opposition—particularly from those concerned with “the means of oppression,” often associated with “White supremacy”. Frankly, I can’t imagine any Democrat advancing a steady-state agenda if their constituency is asked to endorse a policy like this. At best, steady-state economics risks being seen as a luxury concern—something urban populations, grappling with immediate crises, simply can’t afford to prioritize.

Before restrictive population policy becomes a viable part of the conversation in the U.S., we’ll need to confront deeper emotional and social conditions: alienation, rootlessness, apathy, and resentment. These aren’t abstract feelings—they’re political realities. In my view, the first step towards any sustainable future is rebuilding trust and cultivating a sense of mutual thriving and flourishing. Therefore, a more strategic approach to steady-state goals would focus on building civic infrastructure, fostering face-to-face participatory democracy through environmentally-focused civil projects, and implementing a managed immigration policy—an approach with appeal among both Republican and Democrat voters. I can even imagine tying immigration VISAs to federal and state environmental programs as a way to build consensus and steer economics changes which the market won’t foster.

Absent this foundation, any top-down push for population control risks being co-opted by Republicans seeking to restrict immigration for reasons unrelated to steady statesmanship, plunging the issue into partisan conflict and collapsing under its own moral contradictions. Perhaps the wiser strategy for steady-state advocates, at least for now, would be to withhold this feeder bill from the omnibus (?)

Of course, I wish American public discourse was mature enough for this plank of steady-state policy, but living in Chicago, engaged in the political scene here, I see that we are not. Perhaps a more homogenous place like Denmark.

If reduced rather than simply “stabilized population is a critical goal, CASSE’s Commission on Economic Sustainability and legislation such as the Sustainable Population and Immigration Act proposed here may have to countenance added responsibilities or sections. We may entertain, for example, an amendment to this bill that calls for the beefing up of both domestic and international efforts to expand family planning services. Internationally, this would logically take the form of additional U.S. support for the UN Women and UN World Health Organization, where these services loom large and have had significant impact. Domestically, an amendment designed to support the expansion of services under the Public Health Service Title X program (for family planning services) would do the same for U.S. citizens. In both cases, public policy would encourage and add to the natural momentum of the ongoing fertility transition. In the wake of such critical support, the proposed Commission on Economic Sustainability might then count on imminent population reduction alongside its estimates of sustainable immigration and throughput.

Potential amendments to the SPIA, congruent with the goal of population reduction and encouragement of the ongoing fertility transition:

A new section 5:

SEC. 5. DOMESTIC FAMILY PLANNING SERVICES.

(a) FAMILY PLANNING FUNDS— The U.S. Congress shall meet the full funding needs of the Public Health Service Act Title X Family Planning Program, as estimated by the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Population Affairs and in the amount deemed sufficient to fund Title X family planning care for all uninsured women with incomes at or below 200 percent the federal poverty level;

(b) FEE STRUCTURE— Fees for all Title X family planning services shall be limited by the following schedule—

(1) for all patients with incomes at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty level: No fee; and

(2) for all uninsured patients with incomes between 200 and 250 percent of the federal poverty level: sliding scale fees no greater than $25 per clinic visit.

(c) GAG RULE FORECLOSURE— Pursuant to the annual drafting of appropriations for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources, the Congress shall not include any PHSA Section 1008 rule that prohibits Title X clinics from providing referrals or information about or adjacent and distinct abortion services;

(d) ACCESS TO CONTRACEPTION— Pursuant to the annual drafting of appropriations for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources, the Congress shall not include any PHSA Section 1008 rule that prohibits Title X clinics from providing any emergency contraception medications within the prescribed five-day period.

And, a new Section 6(c) [or 7(c) with the addition of the new section 5, above]:

(c) Pursuant to the drafting of appropriations for the U.S. Department of State, the Congress shall authorize appropriations for the period beginning January 1, 2028, equal to 125 percent of the currently authorized appropriations for the following U.N. assistance programs:

(1) World Health Organization

(2) U.N. Women

Thanks for this thoughtful treatment of population and immigration, which as you know are third rails for many who might otherwise be open to a steady state approach to the polycrisis.

I like how you note draconian population policies of the past, since any discussion of population limits will be assailed as sympathetic to these. In fact the vast majority of population stabilization efforts, which achieved enormous advances in poverty reduction and environmental protection globally throughout the 1970s and 80s, were rights-based and voluntary.

I also like the Aid-in-Place Fund and appreciate the acknowledgement of US culpability for the factors that drive emigration. Glad to see reproductive rights as part of that fund: they should be central to it. Nation-states are currently vehicles for horrible international population policy like Trump’s Global Gag Rule; they could, and SPIA could, instead be vehicles for restoration of robust funding for international family planning including both universally accessible contraception & abortion, and the empowerment of women and girls to use them.

In every country where women have access to family planning, birth rates fall – usually below replacement. There is no need for coercion, and no need even for GDP growth. Below-replacement countries should encourage this trend to allow for inevitable increased migration as a result of climate and other calamities in source countries – Brian’s “steady state net migration.”

I appreciate that SPIA envisions a tightening of borders only after our Steady State journey is well underway, if ever. Many of those with the means to emigrate are already in the middle class in their home countries (a class that will include 5 billion people globally by 2030), meaning that their ecological impact at home cannot be dismissed. We should welcome these immigrants, and afford them full access to the family planning services that will allow them to converge with our below-replacement fertility.

One more thought from me, I’ll make some broad generalizations to keep it short:

– explain to the Global South why an SPIA is necessary, via modest but sustained print/television/Internet messaging, basically:

– “uh oh, there is a catastrophic problem brewing, here are some quick examples (Colorado River is used up, etc)”

– “Adding even more people makes it worse”

– “it give us no pleasure to do this, but we have to limit immigration”

– “but take heart, we recognize many of you want a better life, and we want you have a better life”

– “Stay put! Along with fixing the problems in our area, we are committed to help fix the problems in your area”

– “Keep an eye out for the XYZ initiative, which will seek to create a world where everyone has a good life”

Excessive population is the African bull elephant in the room – the single biggest factor driving a global throughput demand beyond the Earth’s sustainable carrying capacity.

I’m working on a range of SD indicators. One of them is a variation on Paul Ehrlich’s IPAT identity. It is the following:

F = P.A.R

where:

F = Footprint (Ecological Footprint)

P = Population

A = Affluence = per capita GDP = GDP/P

R = Throughput-intensity (Footprint-intensity) of GDP = GDP/F

Hence:

F = P.(GDP/P).(GDP/F) = F

Over the past fifty years, at the global level, P has doubled; A has doubled; and R has halved. Let’s assume that, globally, humankind had adopted a policy where an increase in A was only permitted if accompanied by an identical percentage decline in R, thereby allowing the fall in R to cancel out the increase on A. If humankind had also adopted a ZPG policy long beforehand so that P had remained unchanged since 1975, F would be half its current value. F happens to be close to 1.8 times global Biocapacity, so it would currently be less than Biocapacity – that is, it would be ecologically sustainable!

I still have people telling me that population growth doesn’t matter. They say that only per capita affluence (consumption) matters. Of course, they both matter. When I use this FPAR equation to illustrate what has happened over the past fifty years, I often get a hostile reaction from people who refuse to accept that excessive population is a major issue (denialists, in my opinion). One of the most extreme examples occurred, in 2017, when I raised the population issue during an invited presentation at COP-23 in Bonn. If looks could kill, I wouldn’t have made it out of the lecture theatre alive.

Brian, several years ago we invited you to join Scientists and Environmentalists for Population Stabilization. You declined. Now you’ve stolen our motto — “Think Globally, Act Nationally” – without attribution! Phil Cafaro’s advice needs to be taken if CASSE wants to become more than a pie-in-sky-globalist outfit that talks about the Colorado River problems with the same cowardly globalist mindset of the Sierra Club, Center for Biological Diversity, and Population Connection.

Stuart

It’s great to see CASSE thinking constructively about population stabilization. However, I agree with Phil Cafaro that there is neither the need nor the justification to wait for a commitment to steady state economics, before stabilizing national population. What is missing is an understanding of how population stabilization or contraction automatically contributes to social equity and constrains money supply by removing the need for more debt. When debt is being paid down faster than new loans are made, money is cancelled, removing spending power from those who take the interest but increasing it for the poor who are less indebted, and for governments by alleviating the infrastructure expansion treadmill. Meanwhile, a tighter labour market reduces inequality. All of the social conditions Justin mentioned are improved in the context of population decline. See https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106648 for further discussion. Brian infers population stabilization would be costly and require fiscal “fat” when in fact it saves hundreds of thousands per person not added.

Brian also inferred that developing countries might need population growth to drive their economic growth. Nothing could be further from the truth. High population growth, and the burden of trying to “build out” to keep pace, is the main factor keeping them poor. Nor is income growth the driver of fertility decline – the opposite causation prevailed.

Any nation has a right to end or reverse its population growth, regardless of overpopulation elsewhere in the world. Remember that Global Footprint Network doesn’t discriminate between agricultural land and tropical rainforest in terms of biocapacity, so it is ecologically naive to argue people should be evenly distributed according to biocapacity. Alix insists we don’t “own” our country, but infers that it belongs to all humanity, without regard to other species. We can best help people elsewhere by aid and modelling positive population decline.