Population and the Steady State Economy

(Image credit: Sérgio Valle Duarte, Wikimedia Commons)

By Max Kummerow

Sir David Attenborough remarked in a 2011 presidential lecture to the Royal Society that “every environmental and social problem is made more difficult and ultimately impossible to solve with ever more people.” Wherever women’s status has improved and societies modernized, he said, birth rates have fallen. He begged his audience to “talk about population.”

We often hear politicians call for “more jobs.” Growing populations require a bigger economy to prevent unemployment. So if you assume population growth is good and/or unavoidable, you probably favor economic growth to prevent unemployment. And even if there was a steady-state population, the world desires (and some of it needs) higher incomes, more consumption, and more wealth.

Many regard growth as a moral imperative to alleviate extreme poverty. Two billion people still live on two dollars a day. How can their lives improve without economic growth? Attention is focused almost exclusively on economic growth as the path to supporting more people at higher living standards. But there is another path.

A conventional measure of economic well-being is Y/P, or output divided by population (that is, per capita income). Y in this equation represents GDP (gross domestic product). We can acknowledge that a growing GDP per capita may increase wellbeing, but only when GDP is not beyond the optimum level. A growing GDP causes environmental, economic, and social problems. Various measures of well-being (such as the Genuine Progress Indicator, the Happiness Index, and the Human Development Index) help us determine when GDP is beyond optimum. Indeed, numerous analysts inside and out of the CASSE network believe that is now the case – that GDP is beyond the optimum – and perhaps has been so since the mid-late 20th century.

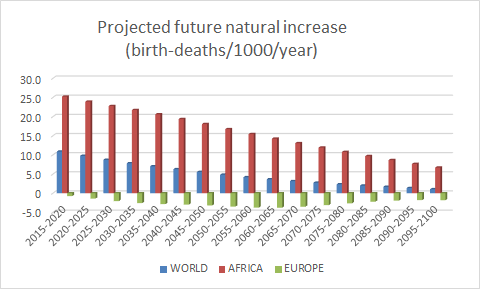

(Graph created from UN World Population Prospects 2017 data.)

In a crowded world facing physical limits to growth, then, why not think more about reducing the denominator? If population falls, we can get by with fewer jobs. There will be more land per family for poor subsistence farmers. Wages will tend to rise and the prices of commodities—housing, fuel, food, etc.—will tend to fall.

To examine the problem if we do not reduce population, let us consider a simple equation comparing the Earth’s carrying capacity—or its ability to provide all that we need from it—with our use of the supply. When we exceed carrying capacity, we also reduce it. Carrying capacity is the Earth interest generated by Earth principal (natural capital, in other words). When we use more in a year than the Earth interest generated that year, we use up some Earth principal, so next year less interest can be generated. Many ecological economists and sustainability scholars have described in theoretical and empirical terms how we are currently over long-run carrying capacity, and we are using up Earth principal (biodiversity, for example). So every year there is less interest and less long-term capacity.

Before family planning, most women bore many children, and infant and maternal mortality rates were extremely high. In The Wealth of Nations Adam Smith wrote, “It is not uncommon… in the Highlands of Scotland, I have been frequently told, for a mother who has borne twenty children not to have two alive” (Book 1, Chapter 8).

In 1970, global fertility still averaged five children per woman. Now the global average fertility rate has fallen to 2.4 children per woman. In about 90 countries, women currently average less than 2.1 children each, which is the replacement fertility rate (two children reaching adulthood for every couple equals replacement). When fertility falls, it takes about 50 years for “demographic momentum” to play out so that growth stops. Young populations have to grow up, have children and age before death rates exceed birth rates. That has finally happened in a handful of countries. Germany and Japan, with declining populations, are doing much better than high fertility countries. Scarcity caused by growth is not alleviated by more growth. Growth is the problem, not the solution.

Country average fertility rates currently range from about 1.1 (Singapore, now one of the richest per capita) to 7 (Niger, one of the poorest). Europe’s fertility averages about 1.7. Sub-Saharan Africa’s fertility rate of 5 children/woman is falling slowly. But death rates by country are falling faster, so natural increase (births minus deaths) is higher now than in 1960 (the current rate is about 2.7% population growth per year).

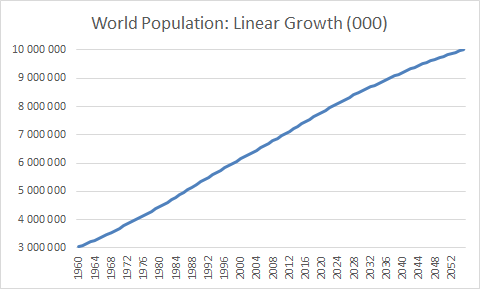

Globally, annual population growth fell from 2% in 1970 to 1.1% in 2010. Meanwhile, world population doubled from 3.5 billion to 7 billion. World population is therefore growing as fast as ever (2% x 3.5 =1% x 7) and increasing by about one billion every 12 years, which means it is headed from 3 billion in 1960 to 10 billion by 2050.

(Graph created from UN 2017 population prospects data.)

Completing the fertility transition in places with corrupt governments and poor people will be difficult. Fundamentalists in all religions have more children. But modernization helps fertility rates fall, especially education and improving the status of women. Low fertility rates in Cuba, Iran, Brazil, Botswana, Thailand, and about 85 other countries shows that fertility transitions are possible anywhere. There are trade-offs, but countries with small families are usually better off economically and their children tend to be better educated.

Lower fertility rates have numerous benefits for individuals, families and societies. It is possible to stabilize world population and to reduce population back down toward global carrying capacity. Education can help change family size norms to reflect the reality that we live on a small planet that doesn’t get bigger when we add more people.

With declining population, the strongest arguments for economic growth disappear, and a steady state economy with universal prosperity becomes both physically and politically more feasible.

Max Kummerow, Ph.D., is a retired business school professor and population activist who researches demography, ecology, and economic development. He has presented papers at ESA, PJSA, NCSE, PAA and EAERE meetings showing the benefits of accelerating the world’s stalled demographic transition toward lower fertility rates.

Max Kummerow, Ph.D., is a retired business school professor and population activist who researches demography, ecology, and economic development. He has presented papers at ESA, PJSA, NCSE, PAA and EAERE meetings showing the benefits of accelerating the world’s stalled demographic transition toward lower fertility rates.

I think we must consider the fundamental reasons driving our current economic, environmental, and social issues, which is over population and capitalism. Together over population and capitalism may do us in but “nature bats last”.

The madness of economic growth which will destroy the planet (or at least most of its inhabitants) but be excused because it improves GDP