Prospects for 负增长 Toward a Steady State Economy in China

by Yiran Cheng

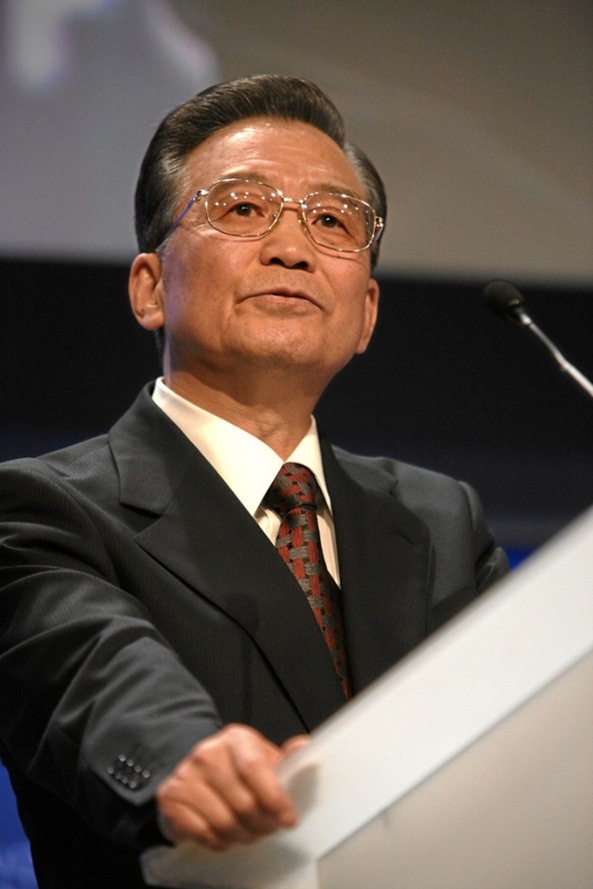

Wen Jiabao: “We absolutely cannot again sacrifice the environment […] for high-speed growth.” (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, World Economic Forum)

This is not to say China is oblivious to its environmental toll. Chinese citizens and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) are well aware of the threat of carbon emissions and climate change. Unlike certain politicians of the USA, recent CCP leaders haven’t shied away from the fact that a balance needs to be struck between the environment and the economy. Starting no later than 2011, the ex-premier Wen Jiabao openly declared that economic growth cannot come at the expense of the environment—a political consensus that was passed on to the current administration under Xi Jinping.

However, even with such an understanding, the domestic discussion on combating climate change or environmental degradation remains interwoven with the premise of growth: green growth, smart growth, etc. I believe that understanding the rationale behind this fixation on growth in China’s unique political and cultural context is required for engaging China in the steady-state movement.

Historic Relationship of the Chinese People with Nature

The Chinese people have had a complicated relationship with nature throughout history. The legacy of this relationship is quite influential in shaping the way Chinese citizens perceive and interact with nature. Amidst all of this history are mythical tales and folk legends, perhaps none so important as the tale of “Emperor Yu Tames the Flood”.

Emperor Yu, tamer of the flood. (CC BY-NC 2.0 , speedygroundhog)

Essentially, the ancient Emperor Yu led the Chinese people to build geographically altering dams, thereby overcoming a flood of biblical levels. Furthermore, and especially in more recent times, Chinese nationalists have used this tale to argue that the Chinese people are perhaps uniquely equipped for conquering Nature. This leads to a core philosophy that is best summed up by a proverbial term known commonly as “人定胜天” (or “humans shall conquer nature” as a crude translation). This guiding philosophy has been around for thousands of years, echoed and reinforced within Chinese society.

This notion that humans can overcome whatever obstacles Nature tosses their way has been quite influential in the decision-making process of Chinese rulers. From the construction of the world’s longest canal circa AD 600 to the much more recent attempts at desert reforestation, the gung-ho spirit to reshape nature as man sees fit can be readily observed. While some of these endeavors could have arguably bore positive results, many others have been ecological disasters; most notably the Three Gorges Dam project, notorious for its severe impacts on the environment.

Contemporary Perception of Growth

As of today, the CCP hasn’t openly expressed any political or economic principles concerning the merits of a steady state economy. In fact, economic growth is still among the top priorities. This is most evident in Xi Jinping’s remarks about economics and the environment in recent years. His speeches on greenhouse gas emissions, carbon neutrality, and the green economy heavily emphasize how such measures must be intertwined with “sustainable and high quality” economic growth.

The hammer and the sickle have swung swiftly at the base of the Chinese economy. (CC0 1.0 Universal, Marx FelipeForte)

This is by no means a matter of pure rhetoric. The Chinese National Development and Reform Commission, one of the most influential departments in Chinese bureaucracy through its agenda-setting powers in economic and political matters, has echoed Xi’s emphasis on growth in its most recent guiding document. The document establishes the objectives of lowering the carbon footprint and transitioning to a green economy while repeating the word “growth” more than 50 times and making it the ultimate goal.

The pursuit of growth is equally potent among the people. With the Chinese economy growing over tenfold in the last twenty years, a new wave of middleclass has appeared in China’s metropolises such as Beijing and Shanghai. Along with this new middleclass comes a wave of state-sponsored consumerism. The freshly minted middleclass is eager to buy the flashiest phone or dress or car to flaunt their newly acquired social status, betting on the economy to keep growing so they can continue enjoying this material comfort. Meanwhile, those feeling envious and left out are praying for another economic boom so they may finally join the ranks of the middleclass.

Multiple Causes of Fixation on Growth

The Chinese fixation on growth is caused by a myriad of factors. Firstly, the aforementioned historic spirit that permeates Chinese society no doubt has its influence over the top party officials and their economic advisors, who might be inclined to believe that sustained growth could be achieved for many more years, if not indefinitely, either through technological advancement or expansion of market access.

Despite furious GDP growth, millions of Chinese are mired in poverty. (CC BY 2.0, Taro Taylor)

Secondly, China is still a country that—in many regions—desperately needs growth. Li Keqiang, premier of China, noted in 2020 that there are still more than 600 million people in the country who have a monthly income lower than 1000 yuan (around 150 dollars). Much of this poverty is due to China’s maldistribution of wealth, indicated by a Gini coefficient of 0.47. However, even with a perfectly even distribution of wealth, China’s GDP per capita of $10,500 would still fall short of what most economists consider a “developed” economy.

In domestic politics, the prospect of growth is the central pillar of the CCP’s rule. As many scholars argue, the Chinese people are willingly trading their political rights for better economic opportunities, and without an ever enlarging economic pie, there wouldn’t be many incentives to tolerate the current political oppression.

Finally, there may even be a second cold war brewing; this one between the USA and China. If, as in the original Cold War, the score is kept with GDP, yet more pressure builds for Chinese (and American) economic growth.

Through the combination of all these elements, the CCP has put growth among one of its top priorities, even using GDP growth as the main measurement in performance reviews for its provincial and municipal party officials. Thus, it’s not hard to see why the CCP is so focused on growing the national economy and using it to measure the performance of its bureaucracy, without much regard to steady-state economics.

Outlook for Steady Statesmanship

While China’s mainstream reception of steady-state thinking is practically nonexistent, the situation is not entirely bleak. Economic scholars from some of China’s top universities such as Nankai’s Maochu Zhong and Tongji’s Dajian Zhu have openly acknowledged the validity of steady-state economics. These scholars have studied the works of Herman Daly and related scholars, and consider the steady-state model a possible alternative to the growth-orientated economic mindset.

Moreover, even though the CCP is fixated on growth, it has become increasingly adept at spinning rhetoric for a positive light when its political performance is ill-performing. An example is the use of the phrase 负增长—degrowth—at least as it pertains to China’s declining birthrates. Thus, if the CCP did decide to adopt the steady state economy as a policy goal, party leaders would simply frame it as a beneficial endeavor for the Chinese people.

The road to establishing broad social support for a steady state economy in China is an arduous one. Even with a better understanding of the Chinese cultural and political fixation on growth, China’s unique political structure and raging nationalist sentiments will prove to be difficult obstacles to navigate around. One thing is certain: The endeavor to reach across the aisles with steady-state words and action—to and from East, West, North, and South—can make or break the prospects for steady statesmanship worldwide.

Yiran Cheng is pursuing a Master of Public Policy degree at Georgetown University and served as a CASSE intern (summer 2022).

CC BY 2.0

CC BY 2.0

The hyper-consumer culture of China (and Singapore, famously) does conflict with some of the older aspect of Chinese culture. The Tang Dynasty poet Han Shan, for example, ridiculed the goal of getting rich. China will face declining ecosystem services (drought has cut ag and hydro power production this year). The saving factor for China might be that declining population should take the pressure for growth off. They can get richer with a shrinking economy, of population shrinks even faster. Another topic: Putin’s folly shows we need to prepare for a hot war with China over Taiwan. The chip manufacturing would be a great prize for the Chinese, and they could confiscate a lot of Taiwan wealth invested in China. Greed and glory motivate wars.

Hi Max, thank you for taking interests in this issue.

I agree, the traditional Han Chinese as well as Confucius beliefs influence people to save more and spend less (as evidently seen in East Asia countries having the world’s highest income-saving rates). However, the government has increasingly started to see that urging against this cultural norm and endorsing consumerism can fuel economic growth. While that might’ve been a good thing while the Chinese economy was still fledging, it will inevitably come into conflict with the environmental reality we now live in.

Great article and thank you.

Very interesting overview of the Chinese view, thank you for this. From steady state economics, I tend to think that the emphasis on *qualitative* improvement over quantitative growth should actually suit Chinese needs very well.

I totally agree! Especially now that China’s population growth has stalled, qualitative growth should become increasingly appealing for policy makers.

Thanks for this article. Great to get these insights.

Where can I get a tee-shirt with this degrowth logo? 负增长

People would ask what it means, and that would give me a chance to introduce the degrowth idea

in a more convivial and entertaining way.

Just take a picture of the ideograms. You probably can have it made for you at many Tshirts shops.

Wonder if the apparent indifference of China’s representatives about their diminishing growth rate over the last 3 years is not linked to a disposition, a cultural attitude, that makes China ready to promote the idea of a “managed growth” which implies renouncing the dogma of “growth at any cost” that has become synonymous with the global West philosophy in economics