The Second Cold War?

By Brian Snyder

Over the past two months, there has been a great deal of talk about the environmental implications of the pandemic. Some have looked for glimmers of hope, others have predicted that we will shortly return to the status quo. I fear that the biggest outcome of the pandemic will not be its death toll nor its effects on the climate, but its impacts on geopolitics. Specifically, the deteriorating relationship between China and the USA may lead to a Second Cold War. If this cold war leads to an all-out GDP race as the original one did, the consequences for humanity will far outweigh the direct human health impacts of the pandemic.

A Second Cold War

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the world may have already been spiraling toward another cold war between the USA and China. The rivalry between the USA and China for economic control of Asia far predates the Trump administration, and the reasons for it are both complex and poorly defined, much as they were as when the iron curtain fell over Eastern Europe. And as in the Cold War between the USA and Soviet Union, historians will eventually find reason to blame both sides for the Second Cold War. Despite these complexities, I fear that future historians looking back at the Second Cold War will note the COVID-19 pandemic as the turning point from economic rivalry to enmity. That is, COVID-19 or, more accurately, Chinese and American leaders’ willingness to blame each other for the pandemic to deflect their own mismanagement, may be the last straw.

A downward spiral: Tensions between the USA and China have significantly increased since the emergence of COVID-19. Could these tensions lead to a full-on Second Cold War, with the score kept in GDP? (Image: CC0, Credit: The White House)

Since the emergence of the pandemic, tensions between China and the USA have increased significantly. Members of the Chinese government have alleged that U.S. service members brought the virus to Wuhan. Simultaneously, the president of the USA has called the virus “Chinese,” refused to accept the academic consensus that the virus likely spread from a wild animal at the wet market in Wuhan, dispatched American intelligence apparatus to prove the unprovable accusation that COVID-19 began in a Chinese lab, and blamed the Chinese government’s secrecy for the severity of the U.S. pandemic.

The original Cold War nearly ended with nuclear annihilation, yet that is not what concerns me about the Second Cold War. The first Cold War ended only after decades of historically unprecedented economic growth in the West was leveraged toward military and technological superiority. This Western growth was nearly matched by the Soviets. If this coming Cold War involves the same growth race, there will be dire consequences for the future of human life on Earth. China and the USA are the two largest economies on Earth, closely followed by the U.S.’s NATO allies, and neither country has anything approaching a sustainable energy supply. If their rivalry ends in the continuing growth of their economies, especially via fossil fuels, the effects will be catastrophic.

This Isn’t (Entirely) Trump’s Fault

While it may be tempting to blame Trump for the looming Cold War with China, it is not entirely Trump’s fault. While Trump’s recent China policy has not helped, tensions with China have been rising for a decade or more. Trump’s confrontational attitude toward China—as seen through the trade war and the pandemic blame—is a product of these tensions, either as a cynical appeal to his base or heartfelt xenophobia.

Many politicians have been claiming for decades that China has been our economic rival. Yet, these same politicians were promoting the globalization of the manufacturing industry for the sake of economic growth. (Image: CC BY 2.0, Robert Scoble)

Trump may indeed be biased against China, and his lack of strategic thinking may be the ultimate blunder that leads us into another Cold War, but there is a reason for his attitude toward China: us. Over the past seven decades, Americans became accustomed to thinking of Beijing as “The Other.” They may not have been the enemy, but Americans have been comfortable viewing them warily, as well as comfortable with politicians telling us the Chinese are an economic rival and a threat to our jobs.

Of course, we were too dim to notice that the movement of manufacturing jobs to Asia could only occur via a globalized world, or that our politicians had built that globalized world to foster domestic economic growth. Thus, politicians have told us out of one side of their mouths that globalization is good for the economy and will make us all the more prosperous, while telling us from the other side of their mouths that our jobs are all moving to China. Remarkably, neither is correct. Globalization will make us poorer in the long term because it leads to unsustainable economic growth, and, until recently, we had more jobs than at any time in our history. The fact that we were near full employment prior to the pandemic somehow failed to alert people of the lie that the Chinese were stealing our livelihoods.

Note that this is not to imply that the blame for this new Cold War, if it develops, is one sided. Certainly, the Chinese government will share in the fault. However, something about logs in eyes should encourage us to focus on our own culpability.

The Cost of a Cold War

But why does it matter if we enter another Cold War? Why would a Cold War with China, if it results from this pandemic, be the most consequential result of COVID-19?

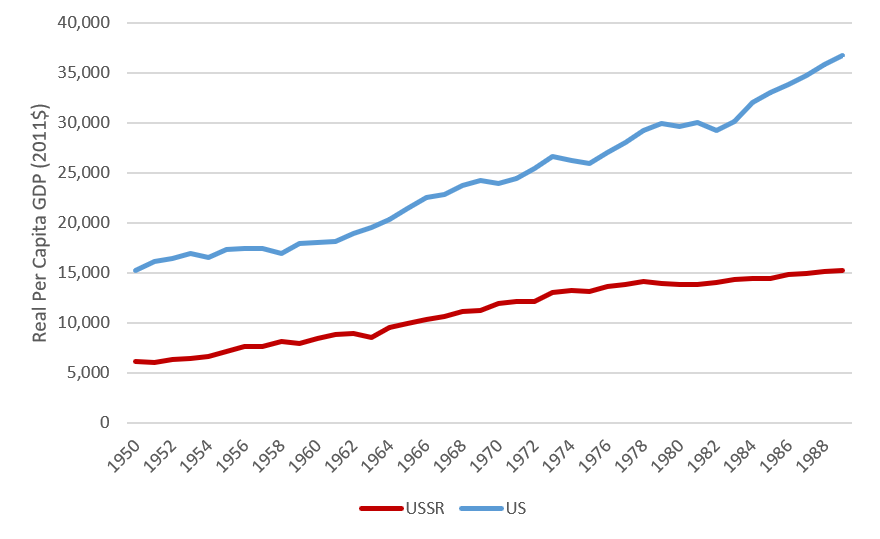

Between 1950 and the Soviet Union’s economic peak in 1989, U.S. real per capita GDP more than doubled, while the Soviet Union’s per capita GDP nearly tripled, according to data from the Maddison Project. If similar growth occurs again over the next 40 years, by 2060 the U.S. GDP would exceed $100,000 per person (in 2011 dollars), while China’s per capita GDP might be $40,000, approaching contemporary U.S. standards.

Such economic growth would require similar increases in energy demand, and this demand would occur both in the USA and China, as well as in their trading partners. These trading partners would export goods to the USA and China and would require increased energy consumption to produce these goods. In some cases, this increased global energy demand may be met with renewables, while in others it may be met with fossil fuels. In either case, it would not be sustainable for two main reasons.

First, renewables, while far less damaging to the earth’s systems than fossil fuels, have environmental impacts. Those impacts may be mitigated with future technology and should not dissuade us from moving away from fossil fuels, but nor should we pretend that they are environmentally benign.

Second, if increased energy demand occurs, it will slow the transition away from fossil fuels. If the USA and China feel the need to grow their economy, they may delay the decommissioning of coal and natural gas-fired power. They may also defer investment in carbon-negative systems, which will be required to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement.

In addition to these changes in energy demand, a second cold war might also lead to rapid technological development which would further stimulate the economy and lead to further energy use. Consider the technologies that emerged largely from investments in the U.S. military industrial complex of the first Cold War: the internet, satellites, GPS, cell phones, computers, and robotics. Consider how much of our economic growth over the last five decades is the result of these technologies. Consider how much of our energy growth and climate emissions result from that economic growth. And consider what will happen if we use our considerable ability to innovate in the service of more economic and energy growth.

Figure 1. Real Per Capita GDP Growth in the US and USSR, 1950-1989

(Credit: Brian Snyder)

Systems Theory

One of the underappreciated advancements of mid-20th century science was systems theory. Applied in numerous disciplines, including in H.T. Odum’s ecology, systems theory rejected the reductionist approaches foundational to then-modern science and argued that the system as a whole had to be understood. Because complex systems are non-linear and emergent, they tend to have properties and behaviors that can’t be anticipated from a view of one isolated sub-system.

Today we are confronted with an extraordinarily complex system. A pandemic presents health and economic challenges; politicians use disinformation to escape blame; and long-simmering rivalries begin to boil. These geopolitical changes incentivize economic growth, and through a bit of chemistry and the second law of thermodynamics, a long-warming planet begins to swelter.

As in the mid-20th century, it should be clear that understanding this system requires a transdisciplinary approach. Issues of climate and energy are also economic, sociological, and geopolitical issues, and we will not avoid our slide toward cold war unless we view all ecological and economic components as a system. Reductionism and retreating into disciplinary silos will lead nowhere.

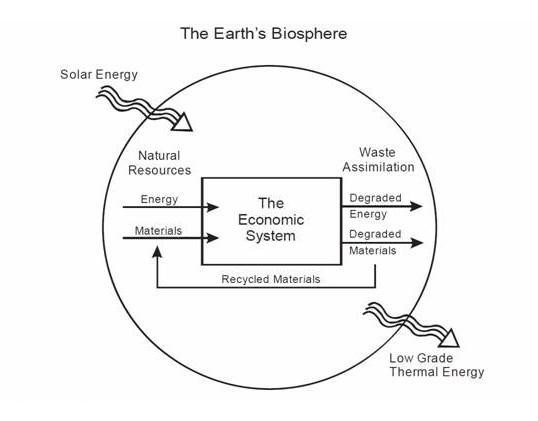

Figure 2. A systems diagram of the earth’s economy, one of the many concepts that developed indirectly from systems theory.

(Image: CC0, Credit: Herman Daly)

How to Dismantle a Cold War

What is especially concerning about this new Cold War is that it will occur in a post-fact, social media-dominated world. Of course, the Soviets in the first Cold War lived in a propaganda-driven, post-fact world, but the West largely did not. Certainly, Western news media in the mid-20th century had a Westernized view of the world, and American politicians tried to spin the news to their advantage, but, in general, Western leaders did not actively and purposefully spread disinformation.

Today information is very different. Like the Soviets, China controls its citizens’ access to information, although their methods are not as effective. But the major difference is in the West, where leaders actively spread disinformation and conspiracy theories. These are then amplified on Twitter and other social media. We have already seen this occur in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, in which alt-right voices on Twitter have spread a variety of false and/or anti-Chinese messages.

This disinformation system—i.e., social media, talk radio, and cable news—is the ultimate cause of our slide toward the Second Cold War. In a circular, symbiotic relationship, American politicians manipulate their traditional and social media followers to spread anti-Chinese messages and conspiracy theories. This makes a significant segment of the public believe that China is a threat to Americans, and it also makes these voters more likely to support leaders who are “tough” on China. Of course, the tough-on-China leaders are the same ones spreading the anti-Chinese messages in the first place. The same sort of relationship occurs with other topics (e.g., climate change), but it is a particular problem in the case of China because nationalism and xenophobia motivate and scare people in a way that climate policy does not.

Thus, to avoid cold war we need to return to a system in which factual journalism is created and disseminated and replaces the current system of disinformation and propaganda. Until that occurs, a change in political leadership will not halt our slide toward the Second Cold War nor prevent destructive economic growth.

Brian F. Snyder is an assistant professor of environmental science at Louisiana State University and CASSE’s LSU Chapter director.

Brian F. Snyder is an assistant professor of environmental science at Louisiana State University and CASSE’s LSU Chapter director.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

(No profanity, lewdness, or libel.)