Redesigning Business for Sustainability

by Daniel Wortel-London

Members of a women’s cooperative in Cameroon. (UN Women/Ryan Brown, Creative Commons 2.0)

Can businesses become sustainable? Certainly—at least in theory. In recent years, new business models have emerged that attempt to place business on an ecologically healthy footing. The doughnut economy, the regenerative economy, sufficiency enterprises, and postgrowth and degrowth businesses: These and other experiments represent ways of doing business that not only create customer and firm value, but address social and environmental needs as well. In a context of limits to growth, such experiments are excellent vehicles for providing the goods and services people need, within boundaries set by nature.

But relatively few businesses are adopting these models. On the contrary: Businesses drive resource extraction and erosion of natural capital and therefore are key drivers of our planet’s environmental crisis. For example, just 100 corporations account for more than 70 percent of global carbon emissions on earth.

Presumably the primary reason businesses aren’t embracing more progressive models isn’t ignorance, greed, or a lack of commitment. It’s a question of design. The way businesses are governed and incorporated tends to promote unsustainable production and consumption and blocks them from undertaking activities that can make a net-positive impact on our environment.

But these designs can be changed—and more and more firms are changing them. Business leaders are broadening business governance to include different voices, expanding corporate charters to include environmental responsibilities, and reforming how their businesses distribute profits. The enterprises emerging through these reforms, from B-corps to worker cooperatives to nonprofit enterprises, are addressing head-on the task of reducing our economy’s environmental impact.

Misaligned Incentives

The way businesses produce, the way they encourage consumption, and the way they design products and choose suppliers have enormous environmental implications. Environmentalists have looked to government intervention to curb bad practices and encourage good ones—through regulations, taxes, subsidies, reporting requirements, and other measures.

A Walmart shareholders meeting. (Walmart, Creative Commons 1.0)

Regulation creates, at best, a hostile relationship between businesses and government (and environmentalists). But the bigger problem is that regulatory tools don’t touch incentives internal to businesses. To change the way businesses make things and deliver services, we need to think first about how businesses are designed.

For example, corporate law in the USA imposes fiduciary duties on directors to act in the best interest of their shareholders. A corollary to this principle is that corporate directors must act to maximize shareholder value, defined in terms of distributed profits. In pursuit of maximized profits, corporate directors can ignore the health of the environment, labor, or local communities in their decision-making. In fact, they can be held legally liable if caring for the interests of these other stakeholders depresses profits.

Alternative Designs

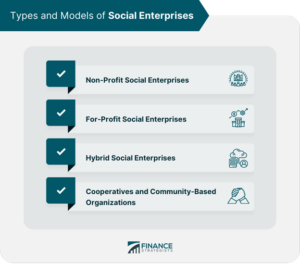

Other ways of designing businesses go to the heart of their operations.

First, we can change the purpose of businesses to incorporate or even prioritize environmental benefits. Most states have adopted legislation creating new legal forms of enterprise, such as social purpose corporations and benefit corporations, that specify that corporate managers must take social or environmental considerations into account when making decisions. These businesses, such as Patagonia, continue to function in many ways as conventional firms. They have products, services, customers, expenses, and revenues like any other business. The difference is that shareholders can’t sue them if these firms decide to forgo profits in favor of environmental protection.

Second, we can change the way businesses are governed. Currently, most answer to a relatively narrow range of investor shareholders. But other ways of governing firms can “embed” environmentalism and worker protection into decision-making. In cooperatives and mutual associations, for example, local workers can ensure that business decisions benefit communities threatened by environmental deterioration rather than geographically distant shareholders. Open-source and commons-based enterprise open the doors to environmental protection even wider. The business “Faith in Nature” has even appointed a “Nature Guardian” to its board. Its job is to give nature a voice and a vote in business strategy. Such governance structures provide an additional internal incentive—and legal grounding—for businesses to take environmental and social considerations into account.

Alternative ways of designing a business to encourage sustainability. (Financestrategists, Creative Commons 2.0)

Finally, we need to take on the elephant in the room: profit. If businesses aim to maximize profit, they will be compelled to maximize production and consumption. This dynamic is difficult to balance with any environmental commitments a business might otherwise have made.

But there are other ways of doing business; nonprofit enterprises are a good example. While these firms buy and sell services like any other, the profit they make is legally required to be used for social or environmental purposes, rather than being distributed to private owners or shareholders. Growth is not the goal; maximizing the firm’s positive environmental impact is. And if making additional profits threatens to reduce this impact, profits are sacrificed.

Together, these reforms of the purpose, governance, and profit orientation of businesses can dramatically shift their orientation toward sustainability. They will be incentivized to respect planetary boundaries not by government fiat but using their own by-laws. Moreover, they could welcome government sustainability initiatives to the extent that those initiatives make their own job easier. All of this can help make an economy more resilient—and more just.

Real Potential for Real Change

Businesses with a progressive orientation do in fact exist. There are currently 6,000 certified B corps in 60 countries around the world, up from 2,500 in 2018. In the EU alone there are more than 2.8 million “social and solidarity economy” firms—more than 10 percent of all businesses!

Moreover, these alternative firms are very successful. Cooperatives routinely demonstrate a lower failure rate than traditional corporations or small businesses: About 10% of cooperatives fail after their first year, compared to 60–80% of traditional businesses. And the potential to convert other conventional businesses to alternative models may be greater than one might expect. Most businesses in America and elsewhere are small and don’t necessary want to expand dramatically. A recent survey of German firms found that only two percent were “growth-driven.” Despite the absence of a growth ambition among the other 98 percent, they operated successfully enough to remain in business.

Most businesses are small, and don’t seek to grow dramatically. Laws should help businesses like these. (Roman Bozhko, Unsplash)

Environmentalists might wonder whether promoting these new forms of business risks generating a “rebound effect” in which reduced consumption in one economic sector is outweighed by the broader growth of that sector. But we need to keep our eye on the goal: reducing the growth of our economy as a whole. We still want to shrink the highest-impact sectors, like energy and agriculture, while increasing product durability as a way of lessening throughput. But increasing product durability will generally increase production costs, which in turn could reduce profits. If we want businesses to adapt to this era of lower profits, we need to encourage new models of enterprise that will help them do so. That’s where public policy comes in.

What’s Next?

Public policy could better support the new kinds of businesses that our environment and economy need. Incorporation laws that enable the formation of these businesses are ad hoc and vary wildly. Governments could procure from, or contract with, existing social enterprises through tools like “community wealth building.” Public bodies could better publicize and promote the role these enterprises can play in addressing our planet’s challenges.

Luckily, campaigns across the world are attempting to change this. More and more U.S. states are providing support to worker cooperatives and B-corps. A coalition to promote “impact-oriented businesses” received the support of three American senators and eighteen representatives in the House. Meanwhile, a campaign in the UK to require corporations to consider social and environmental concerns in decision-making has received the support of 2,000 businesses.

Creating an economy that works for all requires that all step up. (Joe Piette, Creative Commons 2.0)

Too often, however, these campaigns silo themselves from each other. Nonprofit enterprises act separately from cooperatives, who work independently of B-corps. To encourage businesses to transform the way Earth needs them to—to transform their purpose, governance, and relation to profit—these firms need to be working together. And ecologists need to join them.

Not that business reform is by itself sufficient for sustainability. The economy grows as an integrated whole, ultimately limited by agricultural and extractive surplus at the base. (That is the essence of the “trophic theory of money.”) In other words, not all businesses can be truly “green,” even if most can become “less brown.” That’s why there is a limit to economic growth and a fundamental conflict between economic growth and environmental protection. Therefore, macroeconomic policies to cap the size of the economy are a prerequisite to sustainability.

Yet even with steady-state macroeconomic policy, we can’t solve our planet’s environmental crises without the help of business. We need to reform businesses so they adopt environmental protection goals on their own. This means encouraging new legal forms of business: ones that allow the purpose, governance, and role of profit to align with the steady-state goal.

Daniel Wortel-London is a Policy Specialist at CASSE.

Those “100 corporations” are usually just meeting the demand created by many, many millions of consumers. Those corporations would not do what they do if there were no market for their goods and services. They cannot ‘brainwash’ people to the necessary extent. The statistic about CO2 emissions is grossly misleading. The real problem resides elsewhere. It is also misguided to narrow what is a comprehensive ecological crunch, one with many underlying causes not least human numbers, to just one symptom amongst many. The suggestions about alternative business structures are, to be fair, very useful ones.

– Thank you for your response. In my article I said that businesses are “key drivers” of ecological degradation, and never intended my article to say that they were the singular or only cause. I apologize if this was the impression. Also, I agree that these companies are, to an extent, serving an existing consumer demand. The point here is: how can companies, given this demand, change their business models to be less environmentally destructive? And what stands in their way? I tried to address these questions in my article.

Maybe more companies can look at becoming non-profits. I work for a huge organization that is legally a non-profit, and it seems like a good way to go:

– instead of profits going to shareholders, operating income (net gains in money for a calendar year) go to reinvestment, even into financial investments to create a buffer

– the top executives still get paid very, very well. These guys (and gals) are not hurting for creature comforts, believe me

– the planning horizons seem a lot longer than the for-profit companies that I’ve worked for

Does the elephant (i.e. profit) remain in the room for these alternative business models, and if so, can they possibly be sustainable? My understanding of an SSE is that it is operating at levels at which nature can regenerate its productive and assimilative capacities. Humanity is already greatly in excess re consumption levels of these two fundamental functions of the biosphere. And if profit is a claim on future resources, can any business that generates a profit be sustainable? All businesses need to cover costs, including reasonable salaries. But profit generates growth of the economy – the very thing that is destroying the biosphere. While these alternative business models are a step in the right direction, its important to appreciate how far they are from a genuine SSE.

o Thank you for your response. I agree that the overall goal of an SSE is to reduce the economy’s scale to within the planet’s productive and assimilative capacities. This reduction, however, does not entail that certain economic sectors cannot grow relative to others. We can have an aggregate decrease in the economy’s scale while also growing the regenerative economic sector compared to where it is now. To make this shift, however, I argue that we need to adopt new business designs. On the question of profit: the point here is how the profit is used, not whether it exists at all. Both a regenerative farm and an industrial meat processing facility can generate profits: but one will have less environmental impact. We want to promote the former while advocating for an aggregate cap on the economy’s scale.

This is a rather simplistic analysis. Note that the Skadden memorandum does *not* say that it is the fiduciary duty of businesss to maximize profits. That idea was indeed laid to rest by a 2005 report from Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, a leading international law firm. The report, “A legal framework for the integration of environmental, social and governance issues into institutional investment” (Oct. 2005, 154 pp.), was commissioned by the Asset Management Working Group of UNEP’s Finance Initiative. It concluded, on the contrary, that failing to take environmental, social and governance factors into account may be a breach of fiduciary duty. (The study also found that staying short of maximum returns is not illegal under any provision in civil law.)

The Skadden memorandum advises that businesses “explain that particular ESG issues will be examined in light of enhancing the company’s ability to succeed over the long term consistent with its pursuit of shareholder value.”

So what Delaware’s “shareholder primacy rule” calls for is the crux of the matter. Opinions will differ in part as a result of differences in perspective. One could argue that “short-termism” is a form of greed.

Meanwhile, all power to the co-ops, B-corps and social enterprises that meet people’s needs without being driven by short-term profit.

– Thank you for your response. I appreciate that definitions of “shareholder primacy” can vary, and that firms like Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer have argued that it is not the fiduciary duty of companies to maximize profits. The issue here, however, is that current incorporation laws are not clear as to what precisely the fiduciary duty of companies are. It has by no means been “laid to rest,” as we still see debates over what company fiduciary duties are, and the role of profit within them, to this day. You can research these debates online, and I’ll point you to some articles on the topic here. The point of altering business designs is to make clear and legal the fiduciary duties of companies and the role of profit within them,– in this case, to address social and ecological purposes rather than enrich shareholders alone or primarily.

Daniel, I fully agree that alternative business models provide the pathway to a steady state and peaceful world. A leap forward can be taken if such businesses can align with marketing and branding. With clearly identifiable ‘planet n people’ businesses consumers can shift their demand to those suppliers. Imagine an online business portal comprised of such suppliers. These suppliers can create additional brand identities for consumers, like Patagonia. Brand values esposing environmental care can encourage sustainable consumer behaviour. Brand loyalty schemes may enable those loyal to form communities with one another.

Persons not conforming are uncomfortably exposed and start to conform.

The cultural shift away from harmful consumerism is completed as social businesses drain talent from the for profit sector against a backdrop of legacy donations through peoples wills transferring corporate holdings to the social sector.