Reflections on Thirty Years of Worldwatching

Gary Gardner

Looking back. (Library of Congress via Picryl)

It’s been a fascinating experience watching the human family’s response to the emerging sustainability challenges of the past 30 years. Over a career writing on the topic, largely at the Worldwatch Institute, I marveled at the ingenuity displayed by many changemakers. I also bemoaned the blindness and stubborn resistance to change apparent in many sluggards. Here I reflect on sustainability’s ups and downs over three decades.

We are certainly a complex species with contradictory impulses and motivations. Where that complexity will take us as we wrestle with our greatest developmental challenge ever is still an open question. We’ll know soon enough, as the future is arriving quickly! For now, I offer a few simple reflections on sustainability’s ups and downs over the past three decades.

A Hopeful Future?

For most of my tenure at Worldwatch, I believed humanity would get its act together and learn to build clean and innovative sustainable economies. We had (and have) plenty of tools to work with: the steep decline in the cost of renewable energy, the creative thinking represented by circular economies and biomimicry, the renewed appreciation of appropriate technologies such as the bicycle, and the small but vibrant movements preaching the gospel of simple living, to name a few.

On the social side, I was encouraged by the emergence of simple and affordable technologies and practices for improving people’s lives. The simple paste made from peanuts, sugar, milk powder, oil, and vitamins that has saved millions of children from malnutrition. The power of education and healthcare to raise the status of women and open a world of opportunity to them. Decentralized solar-power delivering electricity “the last mile” to rural people in Africa. Solar lamps that stoked educational advances for kids, who now had light for studying at night. And mini-grids that spurred income-enhancing entrepreneurial activity among their parents, who could now run small devices like sewing machines.

No longer just a child’s plaything. (Wikimedia)

Even behavioral science seemed to offer advances for creating a better future. In 2001 I wrote a chapter for Worldwatch’s annual State of the World report entitled “Accelerating the Shift to Sustainability” which explored the drivers of societal change. It touted research showing that peer influence, direct appeals, and enticing incentives are excellent tools for prompting behavior change. One study from the UC Santa Cruz athletic center reported that a sign placed in the shower asking people to turn off the water while soaping up prompted only 6 percent did so. But when a researcher modeled this behavior, compliance shot up to 49 percent. And when two researchers modeled the behavior, compliance was 67 percent.

Surely these and myriad other ideas were the seeds of a new economy and society that would germinate, take root, and blossom into a bright future. We would meet the challenge!

But signs of trouble percolated persistently around me. Friends and family—well-educated people with good hearts—seemed unable or unwilling to grasp what I was learning. “If only you could see the reports that come across my desk,” I would say to my wife, believing that information was surely enough to change minds. That’s why I was at Worldwatch, after all: to digest the science and translate to a broad audience the story of a planet and people in peril.

Yet year after year, Worldwatch’s annual Vital Signs publication documented the steady decline of the planet’s health. An increasingly feverish global temperature. Steady shrinkage of the lungs of the planet, the Amazon rainforest. Clogged arteries as rivers were loaded with pollutants. The cancer-like spread of suburban sprawl. Incomplete nutrition as soils were fed too much potassium, phosphorus, and nitrogen, and too little organic matter. Despite a medicine chest filled with inspiring, nature-friendly treatments, the patient was largely allowed to languish and to grow ever sicker.

Eventually, I kept a mental tally of global issues that were getting better and those that were getting worse. It was an easy list to keep, with the healing of the ozone hole the only entry in the “Good News” column. Everything else—climate change, water scarcity, deforestation, species loss, ocean salinization, desertification, soil erosion, coral reef loss, and virtually every other global environmental issue—fit in the “Troubling Developments” column. For three decades I saw little movement in my lists, even if advances in energy and other technologies have brought limited and localized relief.

Media Silence

As the years passed at Worldwatch, I was increasingly frustrated with the mainstream media’s negligent treatment of the biggest story in human history: the relentless destruction of our one and only home. (The Guardian is the closest thing to an exception among mainstream media.)

I was puzzled, too. What journalist could resist covering humanity’s most colossal misstep ever? Well, nearly all of them, it seemed, despite the story’s potential to be spellbinding.

After all, it featured power plays, in the national and corporate jockeying for resources.1 Greed, in the liquidation of old-growth forests and other resources for fleeting profit. Hubris, as decision-makers stubbornly refused to recognize the long run. Criminality, as corporations stole resources from indigenous people. Delusion and folly, in the human insistence on standing separate from nature. Suspense, in the long-running and insistent question: Would we beat the advancing threats? Thrills, in the courageous actions of heroes from Chico Mendes to Greta Thunberg.

Maybe the story lacked a singular villain. Perhaps it unfolded too slowly for the news cycles. Maybe a global story was too hard to wrap one’s head around. Whatever the reason, journalists seemed to take a pass on the scoop of a lifetime.

Media coverage of sustainability? (Richard Ricciardi, Flickr)

Today’s journalists, despite greater understanding of the issues and episodic coverage of fires, floods, and other disasters, continue to underestimate the dangers rushing toward us. “Enlightened” reporters smugly wag their fingers at climate deniers. But where were these journalists over the past three decades, when sustained coverage could have helped put humanity on a steadier course?

Indeed, where are they today, even the “progressive” ones who give only fragmented attention to the climate crisis, yet provide breathless coverage of every twist in the modern saga of political corruption? Reporters today seem not to understand that the climate emergency qualifies as a—what’s the word? Well, emergency!—that requires emergency-level coverage.

Nor do they understand that the crisis is likely much worse than we realize because current emissions have yet to do their full damage and because emissions continue to rise. Read that emphasis again: emissions continue to rise. Shouldn’t media outlets report emissions levels as faithfully as they do the Dow Jones average?

Even worse, journalists haven’t absorbed that climate is just one of an array of intertwined challenges known as the polycrisis. Any issue from my Troubling Developments list would be of serious concern alone and would require robust policy attention. But the basket of problems taken together is hugely impactful and challenging. A simple example is the chain of causality from fossil fuel burning to climate change to natural disasters to human migration. Who reports on these not as discrete challenges, but as a set of stacked issues?

Finally, and worst of all, few journalists dig to uncover the origins of the polycrisis. The climate crisis, water scarcity, species loss, and other discrete pieces all stem from the same root: economies built on rapaciousness, and ever-growing rapaciousness at that. In other words, the problem is the system, and the growth engine that drives it. Despite pleas for precisely such coverage, when did you last hear any journalist report on that?

Too Pessimistic?

Some argue that it’s too soon to write humanity’s obituary. I’m all ears. Consider the view of Solitaire Townsend, who writes that cultural change is not linear, but happens slowly, then all at once. She points to social science research showing that major social changes—on smoking and health, suffrage, technology adoption, and others—follow an exponential pattern of advance. Pressure for change builds up gradually, then BAM! The change comes swiftly.

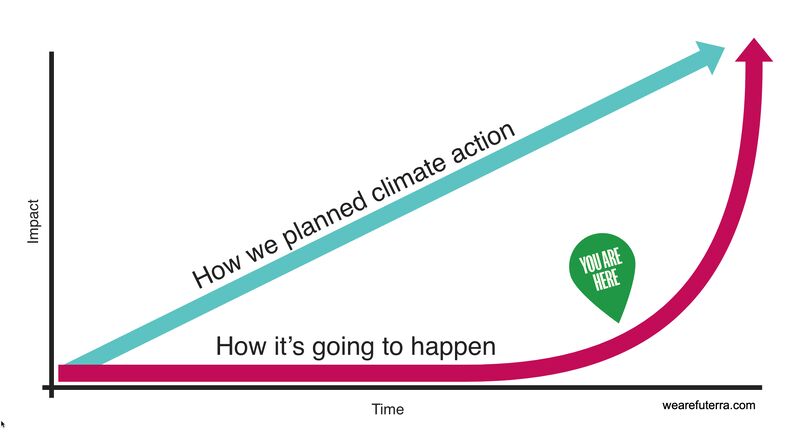

Is something missing? (Solitaire Townsend)

Looking at her chart, I feel the same surge of hope and optimism that fueled much of my tenure at Worldwatch. Hang in there! The cavalry is coming, right there on the red path!

Maybe it is. But I resist the impulse to relax, because the chart is seriously incomplete. It’s missing an upward sloping line shaped like the blue one but depicting the tally of damages. These include the increased suffering of humans from pollution, global heating, noise, congestion, stress, poverty, and many other side effects of overgrown economies. It would also track less observable but momentous damages like species extinctions, depleted aquifers, and a deforested Amazon region. The damages accelerate while the cavalry, apparently having lost its bugle and thoroughbreds, inches forward along the bottom of the graph.

Critically, the impacts are tumbling forward toward risk-filled crossroads. Scientists reported last year that six climate tipping points are likely to be crossed if humanity enters the Paris Agreement range of 1.5 to 2.0 degrees C of warming, which is exactly where we are headed. These tipping points include collapse of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets, die-off of coral reefs, and thawing permafrost, each of which would potentially change the game dramatically for humanity.

It seems we’re witnessing a race between Townsend’s reassuring upward curve and the rapidly approaching tipping points. In spite of substantial advances over 30 years in understanding the challenges we face, humanity’s divergent responses to existential danger remain alive and well.

Picturing the End Game

While I clung to optimism at Worldwatch, I often wondered what our failure to act might look like decades ahead, meaning about now. As the truth of planetary degradation and societal breakdown became clear, would we “get it” suddenly, all of us together? Or would our grasp of the crisis emerge slowly across the population?

Would the conservative media and politicians admit their errors and make amends with a rash of enlightened policies, even if most of these were too little, too late? Or would they double down in their obstinacy, like the officials from the previous U.S. administration who vow to roll back environmental protections if the former guy is elected in 2024?

Our move. (Nils Rohwer, Flickr)

And what about the liberal politicians and even “environmental” organizations pitching the “win-win rhetoric” of green growth? Would they come to recognize the fundamental conflict between economic growth and environmental protection? Or, for the sake of GDP growth, would they keep us eating our environmental cake while pretending we could have it too?

Maybe panic would arise sector by sector, as with the metals executives who penned a letter last week to European leaders requesting an emergency summit. They say the energy shortage related to the Ukraine conflict has shuttered 50 percent of aluminum and zinc capacity since 2021 and increased gas and electricity prices tenfold over the past year. Excited language like “alarm,” “crisis,” and “critical” pepper the letter, along with phrases like “permanent deindustrialization” and “the existential threat to our future.” This is not standard corporate whining but the language of panic and desperation. Should we watch for similar pleas for help from other sectors?

My work at Worldwatch regularly brought to mind the ancient Chinese curse, “May you live in interesting times.” We certainly do. Are we indeed cursed, or might we be on the threshold of a new and sustainable chapter in human history? It’s not clear. But even the hope-filled Solitaire Townsend is arguably hedging her bets when she declares, “The next few years are going to be a wild ride.”

1 John Perkins, Confessions of an Economic Hit Man (Penguin Random House, 2004).

Gary Gardner is CASSE’s Managing Editor.

Homo sapiens. Very smart compared to other species (we even have science!), but very slow to react to new discoveries.

The cause of this slowness to react is found in our forms of government, where science practically does not participate in decision-making.

Sorry disagree, We are clever, and know a lot of clever stuff, but wise we are not. No other creature of whatever kind destroys its own life support system. They live within their limits. We are at the bottom when it comes to common sense and knowing how best to live.

Homo corruptus . Human brains did not develop similarly in all of its parts . The technological part went exponential all the while the empathical part stayed behind .

No longer am i an optimist . I fear for our children’s adulthood for no matter what we do as parents , it is not sufficient At All to cope with the mass destruction on global scale .

Wishing y’all all the best .

Erika

Ah, reasons why I’m not a progress-ive.

The idea that Earth is flat gets deserved ridicule, but the ridiculous concept that Earth is constantly getting bigger is the dominant paradigm of our civilization.

Kurt Vonnegut said he thought the tipping point may have been 1859, when the first oil well was dug in Titusville, PA. That site is a museum now, the oil field is long gone. So it goes.

Man, I know exactly how Gary feels. It’s really hard to know how things will play out, but my gut tells me it will overall feel similar to the polycrisis of the 1930s Japanese/Spanish Civil War/World War II:

– far sighted intelligent people begin to express concern

– intelligent people get really concerned about what they see developing, but are mocked

– intelligent people start freaking out, and are told to calm down

– things start to get bad, with some stunning disasters.. ordinary people begin to worry (estimate: 2023 to 2025)

– things get worse, and some serious mobilization of effort begins

– things get even worse, to the point where ordinary people begin to realize, we might not make it! (2030 to 2040?)

– more really bad news, but also a couple of actual achievements

– the rate of new bad things starts to slow, although the bad news keeps coming

– bad news stabilizes, but at a level that is appalling

– gradually, humanity’s Great Emergency becomes somewhat manageable

– there will be a tremendous re-think of how civilization (what’s left of it) should be organized, and what rules should be abided by. A long term plan to rebuild a healthy planet is agreed upon (22nd century)

Most people throughout the Polycrisis of this century will still die of natural causes I think. And it will be possible, now and then, to have moments of happiness and hope, and even just “fun times” in one’s personal life. But as in late 1945, I think there will be a tremendous sentiment of “why didn’t people listen to the warnings” and “never again.”

My hope is that doing whatever little I can for CASSE will help speed up the process. That’s all any of us can do I think.

Thanks, Cole. Your timeline may well be correct. I suppose what worries me a ton is the social/political disruption that is likely to accompany the events you outline. Many deniers are quite powerful and will not likely go quietly into the night. I hope that some of the mobilization and awakening you refer to happens across a large movement–so large that even the powerful won’t have much capacity to defeat the sane majority. We’ll see. Thanks for the map to the future!

Excellent article. I’d just change the title to “Reflections on fifty years of worldwatching” i.e. since Limits to Growth was published in 1972.

Your mention, ‘“If only you could see the reports that come across my desk,” I would say to my wife’, struck a chord. As I obsessively study the polycrisis/metacrisis, my spouse is unable to muster any curiosity. An episode of tears finally got his attention. Educated, well-meaning people, connected with those of us who “see”, not only feel too traumatized by a peek to look harder, they also are terrified of being required to take some responsibility.

The philosophy that is enabling me to get up each morning is summarized as “you do you”. I take any steps that I consider necessary and within my power, without reference to their insufficiency. Some of those steps are REALLY HARD. I’m in my mid sixties and was forced into retirement. I never achieved confidence on a bicycle. Until this summer. That was scary. Now I’m researching ways to move at least some, perhaps half, my funds out of my retirement funds, which invest in the eternal growth machine, and into something more helpful, like appropriate agriculture. Terrifying.

By setting myself up as a guinea pig for the things we need to ask of people, I can cultivate empathy for all the climate protesters who don’t want to do any of these things. Perhaps a blossoming of empathy will enable me to talk about it without environment-shaming. Maybe someone will say, if she can do it, I can, too. And then maybe someone else. An on-ramp to Solitaire Townsend’s curve.

Beautifully put, Robin. I especially like your connecting praxis and empathy, with the two leading to change via Solitaire’s curve. Rich stuff, and worth pondering…

Excellent article. I have come to the conclusion that it is well past the hour for humanity to have a chance of getting out of the mess we have created without going through a whole lot of hurt. Reason and forethought require hard mental work. Mental work consumes a lot of energy. We evolved as an animal in an environment of scarcity and danger where exercising our mind beyond that necessary to fulfill our immediate needs was a dangerous waste of resources and where the future was never anything much beyond our next meal. We accomplished much despite that very real limitation on our mental capacity but we remain essentially that same animal. The window dressing we call civilization that we managed to scrape together when the world went on forever placed a veil of delusion over that harsh reality that is now being lifted. If I were to hazard a guess I would say that most of those reading here have lived for the most part, despite any troubles encountered along the way, a life of plenty that has left ample time to deeply contemplate what needs to be done to avoid our fall. Yet, even from this privileged seat, I would also guess that most have also experienced the frustratingly persistent difficulty of trying to nudge the needle of our own behaviour even a little. Almost the entire world economy is built on the ludicrous idea that perpetual growth is possible within a finite system. The needle needs a lot more than a nudge. I remain hopeful that we won’t eliminate ourselves completely as we fall and that those that survive will be humbled enough by the experience to find a better way that truly respects our obligation to the future. In the meantime I don’t despair. Instead I try hard to heed a reminder in my calendar that pops up every Friday morning and implores me to “ be better for your kids” in the hope that if I can push myself to move my needle even a little it might, in some small way, ease the pain for those that follow.

Thanks for that insight to your time observing this crises unfold.

Don’t lose belief that information will not change minds. It’s like crowd behaviour. Initially the few first movers start a trend, they’re trendy with a few followers, then it goes mainstream, just like rok n roll. But the issue is the system curtailing the change. The joualists need to sell ad space. During the property bubble, papers full of property supplements, dire warnings didn’t get past the editor.

Modelling behaviour and peer pressure may be the key drivers. Trend setters from the activist end can model the supporting of the not for profit sector. In time we will move from the trend of Nike to maybe not for profit Patagonia. The red path may represent the future growth of not for profits, with the growth economy tipping the other way. Showing peer example is so much more powerful than a sermon of information. That said its a super article and may be better spread with a whatsapp share button embedded for your smartphone readers