Which Future?

by Gary Gardner

Rising or setting? (Flickr)

One of the more puzzling features of modern life is the starkly contrasting visions of humanity’s near-term future. Watch thirty minutes of commercial-filled TV and you get a cheery sense that all is well in the world. A BMW, an anti-depressant, or a Caribbean vacation—these will ensure ever greater happiness.

At the same time, a 2021 poll in ten countries found that four in ten young people are hesitant to have children because of the climate crisis. And a 2022 American Psychological Association survey revealed that 76 percent of adults believed that “the future of our nation is a significant source of stress in their lives.“

Many documents crossing my desk embody these battling worldviews. I describe two below, whose distinct perspectives suggest that the question before us is, “Which future will we choose?” But a third report’s neutral evaluation of the future arguably hints at a more troubling question: “Which future have we likely already chosen?”

Space Vacations? No Vacations?

The first document was a report from McKinsey & Company, that collection of uber-smart analysts who monitor societal trends in search of opportunity and risk. A recent edition of their The Next Normal series, entitled “Could this be a glimpse into life in the 2030s?” featured a survey of a broad range of executives regarding likely developments in the next decade.

The executives’ visions are candy for the imagination. They include vacations in space, and even on Mars; flying taxis; smart packaging (eat your potato chip bag!); packages delivered by drones; immersive and interactive movies; and hotel rooms customized to a guest’s tastes, among others. McKinsey is bullish on the possibilities: “…chances are, in 2035 or thereabouts, much of what’s described…will indeed just be…normal.” So, there’s that. Let’s call McKinsey’s vision Exhibit One.

Exhibit Two is a document from the Post Carbon Institute called “Welcome to the Great Unraveling: Navigating the Polycrisis of Environmental and Social Breakdown.” You might guess that Institute staff is singing a different tune about the human future, and you’d be right. The report reviews the modern “polycrisis,” that mix of causally overlapping global crises that seem to be building to a climax. We’re all likely familiar with the litany of woes: species loss, climate change, deforestation, soil erosion, water scarcity, and collapsing fisheries, to name a few. It also includes social and economic crises from inequality to violence.

Pick a resort. (NASA)

The worsening of these crises and their impacts on society is the Great Unraveling. This unraveling, in turn, emerges from the Great Acceleration, the turbocharged economic activity of the past century characterized by remarkably high levels of materials and energy intensity. The widespread availability of cheap energy, especially fossil fuels, drives the Great Acceleration.

The report speaks plainly: “This unraveling will present a far greater challenge than the recent global pandemic. It will affect everyone, it will persist and worsen, and, if we do nothing, it may not be humanly survivable.” The report asserts that reducing humanity’s planetary footprint is incompatible with a growing global economy. It says that our planet can sustainably support just a few billion people at an equitable level of consumption. And it notes that shortages of critical nonrenewable resources could constrain the energy transition, among other conclusions.

The report’s bottom line is bracing. “The time available to prevent unraveling has elapsed. We have only a brief period in which to find ways to hold together the most vital of threads, while contending with the cascading consequences of misguided human actions to date.” What a contrast to the “all we need is political will” earnestness that concluded so many sustainability reports over the past half century! Notably, the report does not mention vacations of any kind, and certainly not trips to Mars.

Indeed, in reviewing the two reports, I had to wonder if the Post Carbon Institute is on McKinsey’s email list, and vice versa. And if the two organizations are headquartered on the same planet. I did not, however, wonder which of the two perspectives seemed closer to the mark.

A Guide for the Perplexed

Anyone who is unclear about which of these perspectives is more credible could find help in Exhibit Three, a 2021 paper from the Journal of Industrial Ecology entitled “Update to Limits to Growth.” It revisits the 1972 Limits to Growth study and its 2004 update, applying contemporary empirical data to them for a fresh evaluation of the Limits to Growth approach.

The Limits to Growth studies are based on computer modeling that produces various scenarios of the future. These include the possibility of a major contraction of the economy, and the social and demographic dislocation this implies, a scenario it calls collapse. The 2021 update, undertaken by Gaya Herrington, author of Five Insights for Avoiding Global Collapse explores how variables like population, food production, materials use, pollution, and others interact to produce alternative societal outcomes.

Like the 1972 study, Herrington’s study does not predict the future, so her work cannot be used to determine whether the perspective of McKinsey or the Post Carbon Institute is closer to the truth. Instead, her study equips readers to make that determination, by revealing the assumptions that go into creating each scenario. Assess which of the assumption sets is most credible today, and which is the set we’d prefer to see, and you can evaluate each scenario.

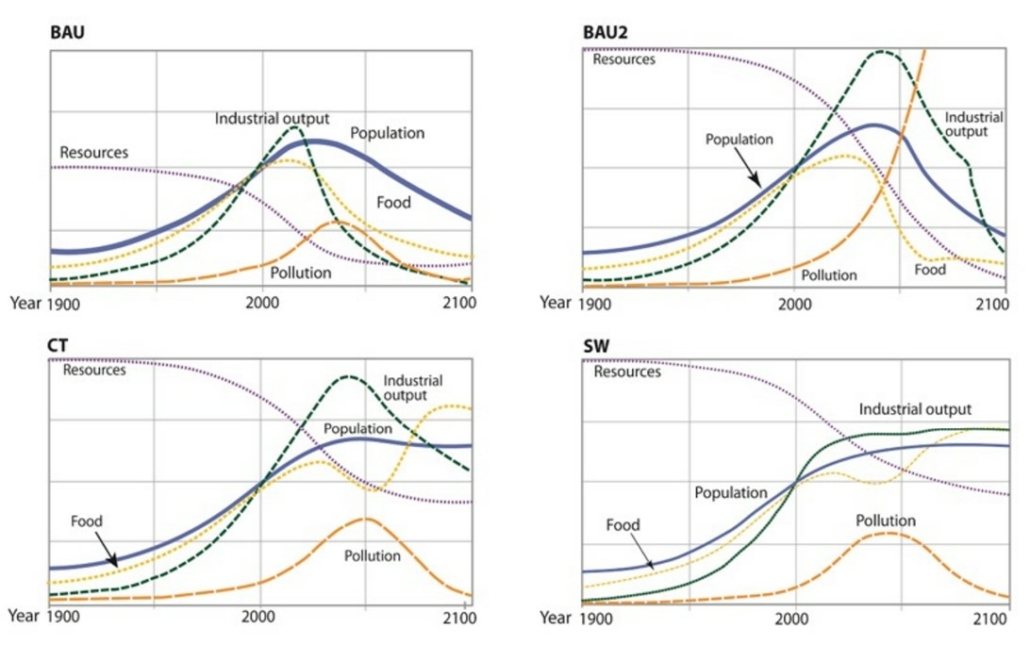

The four scenarios and their assumptions are these:

- Business as Usual (BAU) assumes that materials and energy use, population growth, and the policies that govern them continue their current courses. This scenario captures the worldview of people who don’t follow trends in the economy, energy, pollution and other society shapers. It represents those who cannot or will not recognize today’s gathering ecological and social storm clouds.

- Business as Usual 2 (BAU2) is similar to BAU, but assumes twice the level of resource availability. People comfortable with BAU2 arguably include those who delight in noting that the posted reserves of many resources continue to increase despite steadily increasing consumption. (Just don’t ask them why many resources are increasingly difficult to access and extract.)

- Comprehensive Technology (CT) foresees extraordinarily high levels of technological investment in future economic development. The McKinsey perspective might fit here. Governments can manage resource or pollution constraints using advanced technology and innovation.

- Stabilized World (SW) assumes a sharp shift away from industrial growth and toward investments in health, education, and ecological protection. The Post Carbon Institute would likely favor this one.

Which of these scenarios’ starting points (assumptions) sounds most like today’s world? That we can continue the present course? That resource availability is actually twice the current levels? That technology will save the day? Or that we will abandon the industrial growth model and invest in people and the planet?

And which scenario would you prefer to guide human development over the coming decades?

Having identified your preferred starting assumptions, look at the outcome of each scenario after the model is run.

| Scenario | Assumptions | Outcome |

| Business as Usual (BAU) | Policies and practices can continue their current paths | Collapse, due to depletion of natural resources |

| Business as Usual 2 (BAU2) | Resource availability is double current levels, with no changes to policies and practices | Collapse, due to pollution |

| Comprehensive Technology (CT) | Heavy investments are made in technology and innovation | Steep decline in economy because rising costs for technology eventually cause economic decline, but not a complete collapse. |

| Stabilized World (SW) | The industrial growth model is abandoned in favor of investments in people and the planet | No collapse as the economy and population stabilize, with human welfare preserved at a high level |

Source: Herrington, 2021.

Personally, I’m partial to the “no collapse” outcome associated with the Stabilized World scenario. Little wonder: This is the scenario that looks most like the steady state economy. It’s also the one closest to the Post Carbon Institute vision. On the other hand, I admit that Stabilized World is least likely to prioritize flying taxis and immersive movies.

The figures below depict the outcome of each model. The spaghetti-like trend lines are easiest to decipher by zeroing in on the sharp peaks and subsequent crashes. In the first three graphs, industrial output (the economy) reaches a maximum, then falls sharply—the collapse dynamic. But in the Stabilized World chart (bottom right), the only curve with a peak and crash is pollution! Industrial output and population are both steady—the essential dynamics of a steady state economy.

The timing of the crashes is also interesting. The graphed trends are not predictions, but it’s hard not to notice that industrial output in the first three scenarios peaks before mid-century, i.e., within the next decade or two. Even if the timing is off, the critical dynamic revealed in several scenarios—that of peaks and crashes—should grab us by the shoulders and shake us, no matter when we think it might arrive.

Peaks often spell trouble. (Herrington)

The Comprehensive Technology graph deserves a bit of elaboration given that it did not result in outright collapse and given humanity’s propensity to place faith in technological fixes. First, note that industrial output in the CT graph, while not falling to the extent found in the BAU and BAU2 graphs, does in fact fall, a marked shift from the ever upward trendline of the twentieth century. This represents a major economic dislocation, even if it is not full collapse.

More important, Herrington raises a philosophical objection to the Comprehensive Technology scenario. Even if CT performs better than the BAU scenarios, is it the human vocation to be technocrats, or to be humans embedded in nature? Here is how she puts it:

Why would we use our innovative powers to invent robot pollinators to replace the bees, if we also have the choice to invent agricultural practices that do not have the side effect of insecticide? Why use drones to plant new trees, when we could also restructure our economic priorities so that existing rainforest is not cut and burned down? Now that humanity has attained truly global reach, now that we have an unprecedented power to shape our own destiny, limits to growth force upon us the question: Who do we want to be and what world do we want to live in?

Yes: Who are we and what future do we want? These are essential framing questions.

What Shall We Do?

Back to the future? (PxFuel)

The Great Unraveling report expresses skepticism that government and business will act quickly and robustly enough to avert crisis. (Nevertheless, in my view, citizens should continue to organize on this front). Formidable obstacles stand in the way of effective policymaking, from our focus on the short term and bias toward sunk costs to the growth imperative of capitalism.

Instead, the report focuses on what individuals and communities can do—basically, build resilience at all levels. Psychologically, people and communities need to steel ourselves for the challenging times ahead. Socially, we need robust community ties for effective mutual assistance in periods of stress. And at a practical level, we’ll need to build skills, from gardening and canning to carpentry, plumbing, and electricity, as a means of developing capacity for maintaining and caring for infrastructure.

Lest we lose all hope, we would do well to take to heart one of Herrington’s insights for avoiding collapse. She writes that the end of growth does not spell the end of progress but could mean quite the opposite. Of course, if we insist on comparing a no-growth future to the growth model that promises customizable hotels and adventures in space, we will be disappointed, all the way to the ultimate disappointment of a collapsed economy and society.

But if we focus on assets like strong relationships, health, education, and other measures of wellbeing, we may surprise ourselves. A civilization with a decent quality of life based on renewable energy and renewable and reused materials, and guided by a strong ecological and humanitarian ethic, could offer a path forward that is worthy of the label “human.” Maybe McKinsey & Company, reorganized as a worker’s co-op and managed by the Post Carbon Institute, can get started on this?

Gary Gardner is CASSE’s Managing Editor.

The speaker in the video says that Stabilized World would need behavioral change; In our culture, celebrities become philosophers. We would need a profound change, a culture where philosophers become celebrities. Only then could a critical mass of citizens rise up to thwart the plutocracy. A day when more people know of Epicurus than Elon Musk.

Thanks, Mark. Yes, cultural change is sorely needed. I am encouraged by the often spontaneous and unexpected power of cultural change, as with the antiwar movement in the sixties, the recent advances in civil rights in spite of backlash, and the gains of LGBTQ+ folks in a very short period of time. Nobody saw these changes coming. To be sure, cultural change is not easily planned, like pulling a policy lever. But the advantage of cultural change is that it’s an option open to us all, philosophers and hoi polloi alike. I was intrigued today to read this story about a guy who wants to get rid of lawns, for environmental reasons, so he scattered flower seeds on our national lawn, the National Mall. Who knows where actions that capture the imagination of folks might lead? But we’d better get our imaginations in gear, fast.

Gary, it astonishes me how even relatively enlightened people feel too shy to speak up. I do speak up and am encouraging allies to do so as well. Speech makes a difference.

Hypocrisy also astonishes me. How someone can sound like a fierce climate advocate while planning an airplane trip across the atlantic without dying of cognitive dissonance is beyond me.

Thanks, Robin. I have been at the sustainability gig for a few decades, long enough to have watched a change in consciousness unfold, slowly, across the land, and I often wonder about the dynamics of that shift. How does it work? It’s no great insight that a key piece is the willingness of some–the James Hansens and Greta Thunbergs of the world–to stand up and say what needs to be said. Each such high-profile example undoubtedly represents thousands who take similar stands within their own tribes. “Speech makes a difference,” you note. Indeed, it may be the nudge that eventually starts a movement. Thanks for the point, and for all you do to speak up.

Thanks for your excellent overview of possible futures. I especially like the contrast between “collapse, because scarcity” and “collapse, because pollution.” We don’t really have to resolve the conflict between the idea that peak oil will precipitate collapse, and that climate change will precipitate collapse. It doesn’t fundamentally matter: both scarcity and pollution constitute limits to growth.

In fact, even the “comprehensive technology” scenario could be understood in this way. Technology already gobbles up resources, and this scenario increases the “gobbling” even further. I would question whether we can avert collapse even with technology, but fundamentally it doesn’t matter; we still encounter limits to growth substantially below our present level of consumption.

Why we should be afraid of “collapse” at all? What exactly experiences “collapse” — our political systems, our economy, or what? Aren’t our economy and our political systems precisely the problem? So what’s wrong with that, exactly?

If we shut down half of the fossil fuel industry by 2030, and the other half by 2050 (akin to proposals from ThirdAct.org), what will happen to the economy, even if our elites accept this and even if we have all-out development of renewables? And this doesn’t even address land use issues, which have a massive impact both on climate and on biodiversity. These are the questions that we need to ask.

Thanks, Keith, for your thoughtful response. Certainly we need to greatly reduce energy and materials use, but the collapse path would surely involve a high social and human cost. In the piece I pointed to the crashing industrial output trend lines, but look at food and population in the BAU and BAU2 scenarios. Both crash as well, likely meaning widespread starvation. A softer landing is possible in the Stablized World scenario. But we need to have started that project yesterday, it seems.

Keith, the difference between collapse due to depletion and collapse due to pollution is the degree of damage to the natural world. Collapse of human civilization due to depletion would still cause much suffering and death among both humans and the rest of life, but humans would be unlikely to go extinct. Collapse due to pollution could render the planet uninhabitable by anything other than bacteria, cockroaches, and jellyfish.

This all weighs heavily on all our minds, I am sure.

The only thing I will add to Gary’s excellent essay: I think humanity will inevitably move to a steady state economy, either explicitly or de facto. The real question for me is: will we make the transition voluntarily (much preferred), or involuntarily?

Thanks, Cole. Agree that a voluntary transition, involving many great changes now, is preferred to the involuntary one that will involve a great deal of suffering. I am bothered by the idea that virtually all humans in 50 years will agree that a voluntary transition would have been better, yet so few understand this now. Would that we could borrow votes from the future to make policy today.

Its ok Gary, we’ve got this. Your hopeful closing line advocating the growth of cooperative commonly own suppliers points the way forward. A hurdle to overcome is the buy in of consumers. Its easier maybe cheaper to buy mainstream than from a local coop if you can find one. There’s a low price with more choice and a faster delivery when ordering with Amazon. Consumers invariably go for the best deal. How can we change consumer behaviour so that sustainability overrides convenience and price? The answer, use comprehensive technology as a tool to deliver the nirvana of a stabilised world. We all need to be accountable and responsible for the harm we are doing, a plastic bottle or maybe that flight. CT can tie our card payments to the items we buy and tally our individual environmental efficiency score. Score more when we support coops.These scores can be shared, compared and personal reputations electronically displayed like a personal trust pilot. Cooperation flourishes when our reputations are there to be seen. A voluntary scheme adopted by first movers that may virally grow as the benefits become widely accepted. On the supply side cooperative suppliers can similarly tally the environmental efficiency and societal benefits of their organisations. With the magic of supply and demand a growing community of ethical consumers can support a commonly owned supplier economy, where our suppliers compete to deliver a sustainable and equitable future for us all.

Thanks, Conor. I love your creative thinking. Although objections come quickly to mind (would making public my private consumption choices become a tyrannical invasion of privacy? Is it fair that some would score low on the personal trust pilot because their region lacks the infrastructure, like public transportation, for lower consumption? Shouldn’t the onus be on govt or business, rather than the consumer, to lead on sustainability?) these could likely be dealt with. Would we need a co-operative, democratically run agency–a public-spirited equivalent of Equifax, TransUnion, and Experian–to do this work? Or could it be more decentralized than that?

An excellent piece, Gary, thank you.

Note that, in the Stabilized World scenario, industrial output holds steady, at the global level. Given the huge unfulfilled demand in less developed countries, that must mean significant reductions in consumption and production in the high-income countries. That’s where the pain will be, only lessened when we realize that much of our current consumption (and the production to satisfy it) is wasteful.

Yes, good point, Erwin. There are two periods of pain in the SW scenario: initially, as we end the growth paradigm, and subsequently, as we in wealthy countries downshift. And I wholeheartedly agree with your last point, that we could well realize that lives of relationship, health, and learning are richer than, and preferable to, the consumption-centered lives we are pulled into today. Anyone who can bottle that realization and market it widely will become a legend, with mountains and rivers named after them.

Q Would making my private consumption choices public become a tyrannical invasion of privacy?

A. Sharing ones consumption efficiency score would be a voluntary choice. With the end of a sustainable peaceful world in mind positive steps may be taken.

The early adopters may be activists, customers of social business, or participants within a cooperative living scheme. Motivated individuals are likely to voluntarily to share their environmental efficiency score with the aim of encouraging others to join.

With the compelling end in mind it’s a strong proposition compared to the alternative of BAU1.

Personal privacy need not be inappropriately invaded. Individuals may share their overall efficiency score, not detail every single consumer choice.

It is key that reputations are shared because when they are hidden irresponsibility prevails. In an anonymous society, non contributing free riders are more numerous. They take from the work of conscientious contribution made by others, they discourage that effort.

By accepting a new social norm of voluntarily sharing our effort made to deliver sustainability, we can make the non cooperators, (notable by their absence) uncomfortable and motivated to change.

This is not a big step for most to take, social media has created a sharing culture as I’m sharing with others as I type.

Tyranny, no. Its a voluntary positive step for most to take. After back from the abyss.

Will address more of your questions, hopefully tomorrow.

Q Would making my private consumption choices public become a tyrannical invasion of privacy?

A. Sharing ones consumption efficiency score would be a voluntary choice. With the end of a sustainable peaceful world in mind positive steps may be taken.

The early adopters may be activists, customers of social business, or participants within a cooperative living scheme. Motivated individuals are likely to voluntarily to share their environmental efficiency score with the aim of encouraging others to join.

With the compelling end in mind it’s a strong proposition compared to the alternative of BAU1.

Personal privacy need not be inappropriately invaded. Individuals may share their overall efficiency score, not detail every single consumer choice.

It is key that reputations are shared because when they are hidden irresponsibility prevails. In an anonymous society, non contributing free riders are more numerous. They take from the work of conscientious contribution made by others, they discourage that effort.

By accepting a new social norm of voluntarily sharing our effort made to deliver sustainability, we can make the non cooperators, (notable by their absence) uncomfortable and motivated to change.

This is not a big step for most to take, social media has created a sharing culture as I’m sharing with others as I type.

Tyranny, no. Its a voluntary positive step for most to take. A step back from the abyss.

Will address more of your questions, hopefully tomorrow.

Q . Is it fair that some would score low on the personal trust pilot because their region lacks the infrastructure, like public transportation, for lower consumption?

A. Let’s envisage how this can work well. City dwellers can score well with less private travel, well insulated apartments, efficient goods distribution.

Rural dwellers will score less well.

Firstly, the people we know daily in our lives, usually live in similar circumstances to one another. By sharing comparing, and let’s be honest, competing with one another, we can lower our overall environmental efficiency score among the group we know.

As the system is improved, let’s imagine some more developed personal stats, that can be accessed by tapping on a WhatsApp like avatar. There, one might see an environmental efficiency score that separates out travel, in this way online buddies, living in different circumstances can compare.

Household stats may be shared encouraging families living in similar circumstances to share compare and improve.

In cities people might walk or cycle more. In rural areas people might run E.V.s and install solar panels to help run them. (Sure You’d be the talk of the parish if you had a patio heater :)

With a well developed app, people can access privacy and location settings, enabling meaningful comparisons. When first movers are participating and sharing, questions may be asked of the non sharers, when nothing displays when we tap that avatar. Social pressure may influence them to join in the scheme of measuring, targeting and lowering their individual environmental efficiency score.

In sports and in business you often hear of measuring and then targeting progress towards a defined goal. It’s the sum of our individual environmental performances that will determine the win, the overall outcome. To move towards the goal of sustainability, to improve, we need to measure and know how we are performing

Q. Shouldn’t the onus be on govt or business, rather than the consumer, to lead on sustainability?

A. Business has delivered many of the advances that can enable sustainable living, they can behave sustainably and align brand integrity with customer values. Despite this a compound growth economy, comprised of profit seeking businesses, is inherently unsustainable. (BAU1)

Govts, when lobbied by groups like CASSE, agree to set and enforce, the achievement of environmental targets, while not sufficiently grabbing the issue. They are constrained by the ‘for profit’ driven economies that we all rely on.

The shift to secure long-term sustainability, with the steps that are urgently required, would be a shock for the electorate, a political risk for the ruling politicians, allowing populist opposition to grasp power (on an easy fix promise).

Governments may only be able to lead the necessary change, when given support by populations that have grasped the scale of the problem, and are motivated to significantly change consumer choices.

Consumer aspirations need to change, maybe secured with a reputation sharing scheme as described. This mindset can facilitate stable govts that can then lead.

The prevailing business model needs to move back from striving to profit and grow, back from continuously being policed by govts attempting to halt depletion.

Business, consumers and government all need to be pulling in the same direction.

Can this be achieved with commonly owned coop businesses, competing in a free market to deliver our demand for sustainability?

Can consumers, influencing one another with trust ratings, support and grow those cooperative suppliers. Can a Steady State prevail, dominated with cooperative suppliers, competing to deliver sustainability while using their influence and reserves to promote equality and peace?

Gary thanks for the space to explore this prototype idea, will answer your last question tomorrow or so.

Q. Would we need a co-operative, democratically run agency–a public-spirited equivalent of Equifax, TransUnion, and Experian–to do this work? Or could it be more decentralized than that?

A scheme rolls out from a social business, let’s say a community run food/home goods outlet, not for profit. ‘Caremart’.

Caremart encourages sustainable choices, stocks fairtrade items on the eyeline. A free water chiller by the coffee machine, drinks/bottled water fridge.

Caremart donates to a charity; hospice, Greenpeace, homeless shelter, cancer charity, aid to alleviate hunger.

Customers can be asked to display a marketing sticker iCAREmart 2023 on their car window, maybe their mailbox.

This creates peer pressure, neighbours now need an in date iCAREmart sticker.

The store will have a loyal customer base.

They launch an app planetsaver. An app for the more environmentally aware customers. They might win something free, but it is serious. It’s responsibility to save the planet from destruction, and is marketed as such.

Points are earned by selecting the fairtrade items, lasting-fashion, the lower foodmile items, efficient appliances.

Some engage with this and maintain a score, by regularly buying an expected level of sustainable goods. On the app customers can see if they are a hero or zero with, bronze, silver, gold, or ‘green’ performance bands.

They can go up a level by sharing their score with fellow app users. Encouraged to share and promote the scheme with friends on social media, they get discount or free items for doing well.

The store does well, other social business adopt the same app and share the scheme, the app works across the various social businesses reinforcing the social sector.

With online business the scheme gains scale.

There then can be an overseeing body, tasked with running and improving the environmental efficiency scoring scheme, paid for by the participating social businesses, maybe audited by govt environment departments if it is required.

The LTG model needs updating. We’ve learned, for example, that cumulative pollution (atmospheric carbon) will not necessarily fall when economic activity collapses. Self-reinforcing feedbacks could continue adding carbon to the atmosphere after collapse. And extinction cascades might continue. And soils won’t recover. On the other hand, reducing population seems feasible as fertility rates fall below replacement levels. CASSE should contact system dynamics models to collaborate on an LTG update.

My opinion of McKinsey has steadily eroded over the decades. They have exhibited unethical behavior — helping Purdue Pharma “turbocharge” opioid sales. [see, The many times McKinsey has been embroiled in scandals , https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/the-many-times-mckinsey-has-been-embroiled-in-scandals-43996 . And they have made some outrageously wrong assessments for their clients (e.g., informing AT&T that the future of mobile phones – which AT&T Bell Labs had invented – was a niche market). In 1980, AT&T commissioned McKinsey & Company to predict cell phone usage in the United States by 2000. As widely noted, The consulting group argued that cellular telephony would be a niche market. They forecasted 900,000 subscribers.

How off were they? McKinsey’s was less than 1% of the actual figure, 109 Million. Based on this legendary mistake, AT&T decided there was not much future to these toys.

Now that I’ve read Gaya’s March 2020 thesis, I’d like to add a few more remarks.

Check out Nate Hagens’ interview of Gaya Herrington: “Humanity’s Soul: Life or Growth?” on youtube, or thegreatsimplification.com or your podcast app.

I had to read the thesis to confirm that CT and SW both use the BAU2 resource number. I also learned that SW incorporates all of CT as well as changes in societal values and priorities.The only difference between BAU and BAU2 is the doubling of natural resources for the latter. Given how well empirical data tracks BAU2 (pp. 30-31 in the Results section), I’m not sure I understand the usefulness of continuing to track BAU.

Assuming that the limits to growth concept maps roughly to what Nate Hagens calls the carbon pulse, Dr. Hagens’ @thegreatsimplification youtube video, The Many Shapes of the Carbon Pulse | Frankly #44, minute 18:42 somewhat corresponds with Gaya’s industrial output curves. His precipice curve corresponds to BAU and BAU2. Arguably, if CT were extended to a longer time frame, it may look like Hagens’ stair step dynamic. The industrial output curve of SW seems unrealistic. Continuing the present level of industrial output indefinitely in SW fails to account for the lack of interchangeability between different energy sources and minerals. Considering limitations listed on pp. 57-59 of the thesis, the CT drop-off should look more like the first step in Hagens’ stair step, and SW should level off more like Hagens’ sapient curve.

A purpose of this research was to check the validity of the original LtG models. That is why the models differ from empirical data. It would be interesting to update the models to reflect empirical data, and see how they subsequently diverge from the thesis Results section. It would also be interesting to add in the variables listed on pp. 57-59, plus pandemics and war to future simulations.