True Conservation: A 21st Century Vision for the Next Director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

by Brian Czech

The 21st century challenges to wildlife conservation are unprecedented. The ecological integrity of the nation and planet is unravelling before our eyes. Species and ecosystems are disappearing, if not immediately off the face of the planet, then via slow, dead-end emigrations as they respond to climate change.

It’s not as if climate change was needed to imperil fish and wildlife. Climate change is actually the fourth major crisis in the past 150 years. First was the overhunting that extinguished numerous species (for example, passenger pigeon) and extirpated many others from much of their range (for example, bison). Next was habitat loss: the degradation, destruction, and wholesale replacement of habitats in every state. Think for example of the Florida panther or the San Joaquin kit fox. Third, intimately interlinked with the second, was the pollution of air, soil, and water, most dramatically represented by the buildup of DDT that nearly extinguished the bald Eagle, peregrine falcon, and other symbols of the American wilds.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service needs a recovery plan, based on a vision of True Conservation. (CC BY-NC 2.0, US FWS-Pacific Region)

And now, due to the greenhouse gases emitted by a $90 trillion global economy (driven significantly by the $20 trillion American economy) we have climate change; perhaps more aptly labeled “global heating.” Actually, climate change has been impacting wildlife populations for decades, but we are just starting to realize how ubiquitous and devastating the effects are.

Furthermore, the habitat and pollution crises are far from over. While the growth of the economy has slowed in recent years, it’s not for lack of intent or pro-growth policy. Economic growth remains the overriding domestic policy goal of the USA as well as an American priority in international affairs. As long as this holds, wildlife will be increasingly imperiled and extinguished as habitats are lost and polluted.

Finally, no one should assume the overhunting problem has been solved forever. As the economy outstrips its long-term capacity, society faces a 21st century struggle for subsistence. Widespread poverty will bring more intensive hunting and fishing, liberalization of game laws, and ultimately poaching.

Much has already been lost, but priceless populations and species of wildlife hang in the balance. American taxpayers are counting on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) to lead the way in protecting our wildlife heritage. Who else would they expect to do the job?

The problem is, the agency has lost its way. That’s my opinion, after nearly 20 years at FWS headquarters (ending in November, 2017). Inconvenient truths have been shrouded for the sake of perks and pleasures among the higher ranks. No one person is going to fix the FWS, yet some individuals are especially important to the future of the agency. None is more important than the director, and the Senate faces an impending choice on who to appoint.

Herein, I propose a vision that the FWS director will need in order to be effective. I’ll call it “True Conservation.”

Professional Background, Personality, and Priorities

A vision of True Conservation isn’t possible without certain intellectual prerequisites. That’s not a reference to intelligence; that trait should go without saying. Rather, I’m referring to a mastery of particular fields of knowledge. For starters, the director must be an expert in wildlife biology and ecosystem ecology. An FWS director without such mastery is like an attorney general without a law degree or a treasury secretary without an economics education. Given the glut of wildlife biologists, a bare minimum of a master’s degree should be required.

Yet expertise in wildlife science is far from sufficient for True Conservation. An effective director must be an expert on the threats to wildlife. Otherwise, how will they know what to fix and how to fix it? A busy stint as director, which will come and go in a flash, is no time for figuring it out. The director must come in especially with a solid grasp on the fundamental conflict between economic growth and wildlife conservation. She or he (hereafter, “they”), in other words, must have a solid background in ecological economics; in particular, ecological macroeconomics.

Passion is another prerequisite, but it must originate for the right reasons and apply to the right things. Let us not mistake outdoors enthusiasm for conservation passion. It’s not enough to be a passionate hunter, fisher, or birdwatcher, or a passionate defender of the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation. A True Conservation director will be willing to sacrifice fun times in the field in order to conduce the political, policy, and cultural changes required to slow the runaway train of economic growth. A vision short of that is High-Paid Fun in the Field, not True Conservation.

The FWS director must be politically savvy, not for purposes of personal advancement, but rather for deft and timely rhetoric. The 21st century director needs the ability to subtly undermine or outright refute the catastrophic win-win rhetoric that, “There is no conflict between growing the economy and protecting the environment.” Opportunities to refute such rhetoric will come every single day, seven days a week, 365 days a year. They must be taken while the director has the podium and the position.

True Conservation Themes

The FWS director will face a panoply of conservation challenges. They must wisely appoint the proper assistants to handle most of these challenges, because the director must maintain a focus on the big-picture, long-term themes of True Conservation. The most important themes will be a conservation ethic, steady-state economics, land conservation, ecological integrity, protecting the Endangered Species Act, conserving biodiversity, and adapting to global heating.

Wildlife conservation is a pipe dream without a truly widespread conservation ethic. It is up to the director, as much as any other figure in the federal government, to cultivate such an ethic. This doesn’t take a degree in sociology or psychology, much less marketing or advertising. (The latter, especially, would be cynically ironic.) Rather, it requires a passionate exposition of the diversity and wonder of our American wildlife, along with the small and simple, everyday practices that conserve our resources and therefore our wildlife.

The director will have an entire agency as a crucible for cultivating a True Conservation culture. The director should commence cultivating on day one from their very own office. The lowest-hanging fruit is the light switch. Shutting the lights off will be a message to assistant directors, other staff, and visitors.

It’s not enough to talk about Aldo Leopold, leave the lights on, and go eat a steak. If you can’t walk the talk, don’t walk to the podium.

Conservation practiced in the halls of FWS—starting at the director’s office—will emanate to the Department of the Interior, other agencies, and ultimately the American public. After a few months of mastering the messaging in-house, the director should do all in their power to get the True Conservation message out to the public. This will be within the director’s purview, with resources such as the National Conservation Training Center, visitor centers, and an entire communications staff at their disposal. “Turn out the lights, use your own mug, and bring your own bag.” That’s a message all Americans will find relevant, not just wildlifers.

“Nothing could be more salutatory at this stage than a little healthy contempt for a plethora of material blessings,” Aldo Leopold wrote in his 1948 preface to A Sand County Almanac. Leopold would have little patience for FWS rhetoric of “stimulating the economy.” (Courtesy of the Aldo Leopold Foundation and University of Wisconsin-Madison Archives)

The next major theme in True Conservation is steady-state economics. This doesn’t mean the director should, upon the inaugural day, issue a press release renouncing the Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act of 1978. What it means is, from the very start, the director should be taking baby steps toward correcting the fallacious win-win rhetoric, and lengthen those steps throughout their term.

Chances are the director may never utter the phrase “steady state economy” on television, over the radio, or even before Congress. They can leave a lot of that to the next director. However, this director—the one to be appointed by President Biden—needs to get the ball rolling and cannot abide ignorant notions of “green growth.” However subtly the occasion calls for, the director must interject with pithy lessons on limits to growth, the conflict between growth and conservation, and in some venues, at least, the steady state economy as the sustainable alternative. By now, the director will find plenty of empowerment in the long list of true conservation giants—Jane Goodall, Sylvia Earle, the late E.O. Wilson, and so many others (including past FWS director Lynn Greenwalt)—who have put their good names to the steady-state mission.

True Conservation absolutely requires land protection. Any FWS director will have a head start at the helm of the National Wildlife Refuge System: 568 national wildlife refuges encompassing over 800 million acres. Don’t be misled by the heady figures, though. The vast majority of acres (over 700 million) are offshore and largely titular, reflecting a political contest during which presidents Bush and Obama “designated” marine conservation areas, but with weak teeth, as a subsequent, GDP-obsessed president quickly demonstrated. Second, of the 95 million terrestrial acres, most are over large expanses of Alaska where little else would have occurred anyway. (Such acreage is cynically referred to in conservation circles as “rock and ice.”)

That said, over 20 million acres of national wildlife refuges in the contiguous 48 states are jewels of wildlife conservation, from the tiny Watercress Darter NWR (Alabama) to the sprawling Desert NWR (Nevada). Protecting these refuges will be one of the greatest privileges in the director’s life. They better understand the threats.

When the director thinks about land protection, they should start with one key question: What is a national wildlife refuge a “refuge” from? By now it should be clear what the answer is: the economy. Agriculture, mining, logging, domestic livestock production, commercial fishing, manufacturing, urbanization/services, and the infrastructure that ties it all together such as roads, power lines, and canals; these are what the director is charged to protect the Refuge System from.

National parks, too, are refuges from the economy, albeit with different purposes. In fact, all units of the conservation estate including national forests, Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lands, state parks and forests, and county parks are to some degree refuges from the economy. Yes, many of these lands are used for limited economic activities—most notably logging on national forests and cattle grazing on BLM lands—but overall, the economy is precisely what these lands are protected from.

The problem is refuge lands will be under constant pressure to produce, and not just for outdoor recreation, but the supposed “higher and better” economic uses. The pressure will come directly from the private sector and from other, growth-oriented government agencies, directly and indirectly, as many of these agencies assist the private sector for purposes of GDP growth.

The director must start making inroads to higher levels of government. The greatest hope for a breakthrough in macroeconomic deliberations at the Cabinet level lies with the Secretary of the Interior. Such a breakthrough is highly unlikely unless the Secretary is first informed by, and can subsequently lean on, a knowledgeable FWS director, who must drive home the point that the FWS mission is undermined by the goal of GDP growth that has permeated the government. The director will need to recruit allies from within FWS and other Interior agencies in this effort to get the Secretary conversant with the fundamental conflict between economic growth and not only the FWS mission, but much of Interior’s collective mission.

Meanwhile, partly as a result of encroaching economic activity, and largely as a result of global heating and other ubiquitous threats (for example, proliferation of “forever chemicals”), the director will face tricky decisions even on the protected lands of the Refuge System. Pursuant to the National Wildlife Refuge System Improvement Act of 1997 (Refuge Improvement Act) and the subsequent “ecological integrity policy,” known to FWS insiders as “601 FW 3” (Part 601, Chapter 3 of the FWS Policy Manual), the rule of thumb is to manage refuges consistent with natural conditions. This is a philosophical cornerstone, not a cookie-cutter prescription. Exceptions may occur, especially when a refuge was established with other purposes legislated (for example, certain industrial activities at Crab Orchard NWR in Illinois).

Some at FWS have thrown their hands in the air, correctly acknowledging the game-changing effects of global heating, but incorrectly proclaiming it’s game over for the ecological integrity policy. They’ve based their forfeit on the incorrect impression that the policy requires refuge managers to forever maintain natural conditions. As the lead author of the policy, I know that was never the intent. Rather, the ecological integrity policy simply requires refuge managers to assess what natural conditions were, based upon historic records and the archaeological, anthropological, climatological, and ecological data. All else equal, then, if a management action would take the refuge even further from those natural conditions, it would not be advisable (for example, managing for an artificially high ratio of game:non-game populations). Also, a management action itself can be less natural than others, and therefore less preferable (for example, using herbicides to reduce woody vegetation, rather than prescribed fire).

In the original policy—the one that would have passed with strong directorship—my policy team included a chronological frame of reference for natural conditions spanning the millennium from 800 AD to 1800 AD. This allowed for substantial plant community succession and evolutionary pathways accommodating warm and cool periods (Medieval Warm Period and Little Ice Age, respectively). The latter endpoint (1800) was designated not so much because of the mere introduction of industrial technology, but rather the rampant acceleration (“take-off” as W.W. Rostow called it) of the economy as wrought by industrialization, and therefore the rapid demise of wildlife habitats and populations.

Unfortunately, the directorate leadership, down to the level of the Refuge System Chief, caved into political pressure and deleted this crucial element of the policy. However, the concept was kept alive via Natural Resources Journal. A chronological frame of reference—essential for any comparison of conditions—helps us to understand that naturalness is no longer possible, but is still an ideal to hold to.

Vince Lombardi gave an imperfect analogy when he said, “Perfection is not attainable, but if we chase perfection, we can catch excellence.” The director must hold fast to the concept of ecological integrity, or may otherwise lose control of the Refuge System and see it turn into a circus of hunting reserves, shooting ranges, zoos, concession stands, and who knows what else for purposes of “stimulating the national economy.”

While the Refuge System is important for wildlife conservation, education, and research, refuges are a miniscule fraction of the 48 contiguous states. The director must be a passionate defender of lands, public or private, especially in cases where a species is under imminent threat. This brings us to the next theme, protection of the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

The ESA cannot be understood, much less effective, without an awareness of its economic nexus. It was designed as a collective stop sign. If a project is going to further imperil a federally listed endangered species, it encounters the ESA stop sign. Otherwise, by definition, that species is firmly on the road to extinction. Fortunately, the stop signs are easy to see from a distance, and rarely create hardship for well-planned business enterprises.

Unfortunately for wildlife, projects (commercial and public alike) proliferate in lockstep with GDP, many of them are poorly planned, and the causes of species endangerment are like a who’s who of the economy. That’s why the ESA is nothing less than a prescription—albeit an implicit one—for a steady state economy.

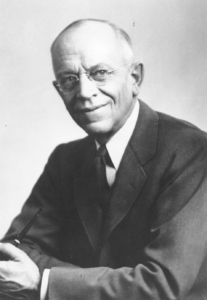

Lynn Greenwalt (second from right) stood out at FWS for speaking truth to power. (CC BY 2.0, americaswildlife)

The director’s challenge, then, is not to hide the meaning of ESA and try to sneak it into the political end zone with the win-win rhetoric of “green growth.” The challenge starts again with the baby steps of raising awareness—one mind at a time—that in fact we cannot have our cake and eat it too. The ESA is not the enemy. In fact, it is much like a friend, warning us against unsustainable behavior such as gluttony or recklessness. We really ought to cherish this friend, not ignore it, much less gut it in Congress.

The director with a True Conservation mission will also resist the temptation to emphasize “game” management purely for the pleasure of hunters and fishers. We thought those days were behind us by the time I was hired (1999) as the first “conservation biologist” in FWS. The principles of conservation biology—most importantly the conservation of biodiversity at large—were behind the Refuge Improvement Act and subsequent FWS visioning exercises such as Fulfilling the Promise and Conserving the Future. Just because one president was so obsessed with GDP growth that even the conservation agencies were brought to bear for “stimulating the economy”—including ramped up sales of arms, ammunition, and all manner of hunting and fishing gear and activity—doesn’t make that shameful episode a legacy to retain. Refuges cannot be treated like another pawn in the chess game of GDP growth. Yes, hunting and fishing is compatible with many of our national wildlife refuges, but on very few refuges (those with legislated exceptions) should it be a top priority. That wouldn’t be True Conservation.

Finally, and coming full circle, the 21st century director must have a cogent response to global heating; that is, a problem-solving approach that addresses the root cause. This is no place for regurgitating a primer on climate change and the Refuge System. In the long-term big picture, it just doesn’t matter if FWS builds a dike here or rescinds a fire prescription there. The real point for True Conservation is that the director must help to magnify the staid assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that the single most driving variable in greenhouse gas emissions is GDP.

Institutional Reform

The incoming director will have plenty of in-house clean-up to do, too, especially at headquarters. Among other things, FWS suffers from poor hiring practices, outdated training priorities, conservation hypocrisy, suppression of science, and the low morale that comes with all the above. None of these problems are intractable. I’ll offer just a few ideas for reform, enough to help buttress a True Conservation vision from within the agency.

Given the aforementioned glut of well-qualified wildlife biologists, a graduate degree should be required for biologist and manager positions. (No more boasting by sons of earlier employees that they managed to land a biologist job without a graduate degree.) Merit-based civil service hiring procedures should be strictly applied, and supplemented with additional requirements if necessary, so that a chief can’t come into headquarters and summarily hire a staff of drinking buddies from the field. This entails hiring by a committee of peers from other programs, without the involvement or input of an immediate supervisor. Any downsides to this approach are outweighed by the proven penchant for cliquish hiring.

Given the True Conservation themes—conservation ethic, steady-state economics, land conservation, ecological integrity, protecting the ESA, conserving biodiversity, and adapting to global heating—the director will need to revamp the training curriculum at the National Conservation Training Center (NCTC). Training on the conservation ethic and land conservation are reasonably developed already. The other themes could use some work, and the theme that stands out as in most need of development is steady-state economics.

Given that True Conservation is essentially a steady state economy, FWS seems almost like a sham without a basic understanding of steady-state economics at the staff level, and substantial knowledge of it among the leadership teams. Every FWS employee ought to be conceptually equipped to describe the fundamental conflict between economic growth and biodiversity conservation in venues ranging from the elevator to the conference podium. FWS leaders should be able to hold their own in the inevitable debates with economists and “green growth” salesmen, and to proffer a vision of steady statesmanship in the Senior Executive Service and potentially at higher levels in the Administration and Congress.

The conservation ethic is taught about in some NCTC courses, but that doesn’t mean it’s taught. That’s going to take True Conservation leadership. Meanwhile, “conservation hypocrisy” ranges from leaving the lights on to investing in oil companies via the Thrift Savings Plan. One of the most reprehensible—and most correctable with True Conservation—is the tendency of FWS chiefs to treat their jobs like full-time tourism. There’s always an excuse to travel to a refuge for “oversight,” a conference for “networking,” or even a foreign wildlife agency for “consultation.” Yes, some of these events are legitimate, but if a comprehensive travelogue of FWS chiefs were published for the past few decades, it would be scandalous, especially accounting for the per diem “costs” that are substantially pocketed. Given the carbon footprint of airline travel, the hefty price to the public, the easy access to online conferencing, and the backlog of duties at the desk, FWS (and other government) flights should be phased out, if not by law then by director’s order.

Suppression of science is a nefarious phenomenon. Not only is truth and reality hidden from the taxpaying public but, to put a slight twist on Donald Rumsfeld’s lament, we don’t know what we don’t know. By the very nature of a gag order, we can never really know how many government employees have been gagged, on what topics, for how long, or why. It’s a slippery slope, shutting up an employee or shutting down a topic. Every scenario is different, but in True Conservation, an FWS director doesn’t gag a biologist for raising awareness of the trade-off between economic growth and wildlife conservation. If ecological macroeconomics is a strong suit of the employee, the director recognizes the value and cultivates it rather than snuffing it out. They consult with the employee and either incorporate the knowledge into FWS programs, bring it to the attention of the Secretary, or, if politically vulnerable, work out an assignment for the employee in a more durable agency such as the State Department, while FWS works on developing the wherewithal to deal with the “800-pound gorilla.”

Although there would have been exceptions among a “hook-and-bullet” cohort, FWS morale probably reached an all-time low at FWS during the Trump Administration. (It hadn’t been very high since 2014, when most headquarters staff were moved to cubicles in Falls Church, Virginia.) The covid pandemic hasn’t helped, because it’s kept a lot of already-insecure staff further in the dark of telework. Furthermore, I believe that each of the institutional shortcomings noted above, plus of course the sweeping sociopolitical challenges to ecological integrity, have discouraged the majority of FWS employees. Morale must have reached rock bottom when Aurelia Skipwith, Trump’s FWS director, told employees in an all-hands meeting that she’d gone back to law school after being constrained by the law while working for Monsanto.

If the next director leads strongly on the themes of True Conservation and fixes the antiquated, corrupting institutional problems at headquarters, morale will soar! Practicing as well as preaching conservation will garner respect. Steady-state economics—with only the basics required for staffers—will refresh a workforce that otherwise faces a growing sense of futility. Not giving up on ecological integrity will ensure employees that they’re working for the long term, not just a generation or two of hunters and fishers.

Finally, extinguishing the win-win, no-conflict rhetoric will boost morale by excising the cancerous tumor of conservation cynicism. Yes, there most certainly is a conflict between growing the economy and conserving wildlife. The Wildlife Society, U.S. Society for Ecological Economics, American Society of Mammalogists, E.O. Wilson, Jane Goodall, Lynn Greenwalt, and many other leading conservation individuals and organizations have acknowledged and explicated it. It’s long overdue for FWS to do likewise. Only when enough acknowledgement exists in the polity can the conflict be responded to wisely.

Brian Czech is the executive director of CASSE. He served as the first conservation biologist in the history of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service from 1999-2017.

Brian Czech is the executive director of CASSE. He served as the first conservation biologist in the history of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service from 1999-2017.

Right on.

good essay but another True Conservation theme has to be – seeking a sustainable population level – because we are already way over it.

I’ve always appreciated your vision, Dr. Czech. I enjoyed reading this and hope the powers that be are listening to you!

My FWS career spanned 1983-2017, most of it spent as the deputy dawg of the Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program. (So, an FWS employee, but working for ten partners, of which FWS is one.) I read your “Shoveling Fuel…” when it first came out and found it a great encouragement. The Colorado River program has often been called a model of collaborative conservation and, yes, sometimes referred to as a “win-win” (for fish and human water use). In reality, I think it’s a partnership that offers the only currently possible way forward for the imperiled fish in the heavily used Colorado River system. We made big strides getting folks to cooperate in water management so fish have some water, etc., but it will always be a managed system as far as I can see. It’s possible we’ve even convinced some water users that, as you say, “The ESA is not the enemy. In fact, it is much like a friend, warning us against unsustainable behavior such as gluttony or recklessness. We really ought to cherish this friend, not ignore it, much less gut it in Congress.”

However, we’ve is much to do in conservation and FWS, in particular, to convince folks that: “It’s (NOT) the economy, stupid” and I’m so grateful you’re pushing hard. As my program partners had to read in my tagline for oh-so-many years, “As long as we worship at the altar of individual self-fulfillment, personal freedom, and material success, we’ll be good stewards of nothing but our own shortsighted selfishness.

Keep up the great work, brother, you’re doing the Lord’s work, for sure!