Cracking the Code: Finding “Economic Growth” in Statutory Law

by Daniel Wortel-London

A chapter in the U.S. Code entitled “Statements to accompany significant regulatory actions” contains a critical directive. It declares that any notice of proposed rulemaking by a federal agency that may result in expenditures of $100,000,000 or more must be accompanied by an estimate of that rule’s effect on economic growth.

Take out your editor’s pen. Imagine amending this code by replacing “economic growth” with “economic stability.” How might this simple change transform the purpose and operation of federal laws? And could this help to steer the U.S. economy toward a steady state?

Some 323 references to “economic growth” are found within the U.S. Code. (Tony Webster)

This directive is only one of the more than 73 binding references to the term “economic growth” found within the U.S. Code, the official compilation and codification of permanent federal laws passed by Congress. Such directives can be found in bills pertaining to fisheries and global trade, highways and banking, conservation and space commerce. They can take the form of vague exhortations or firm requirements. And all of them entrench “economic growth” as an overriding goal of federal policy.

CASSE’s goal is to change this. By replacing references to “economic growth” within the U.S. Code with references to steady-state objectives, we can fundamentally alter the priorities and activities of the U.S. government. To do that, I’ve begun compiling and analyzing mentions of the term within that code. This exercise helps reveal the places of greatest leverage for rewriting federal laws and moving our nation’s economy toward a steady state.

Numerical Analysis

To compile substantive references to economic growth in the U.S. Code, we must first understand what the Code is. The Code is organized by subject matter into 54 titles, each of which is further divided into chapters and sections. For example, the establishment of the National Highway System can be found in Section 103 (National Highway System) of Chapter 1 (Federal-Aid Highways) of Title 23 (Highways).

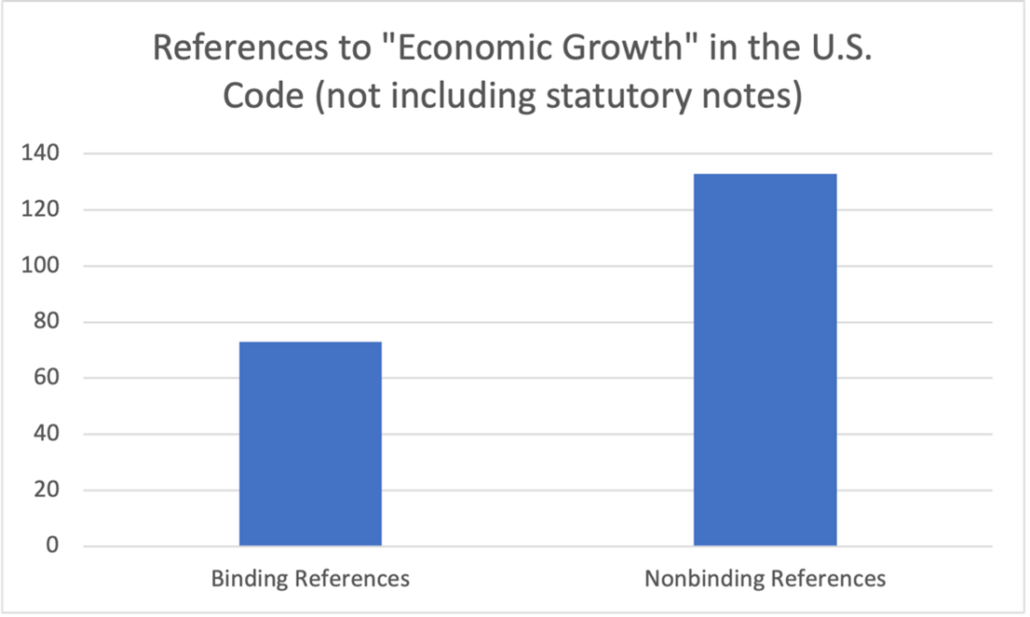

A quick search for “economic growth” in the Code pulls up 323 hits. But finding substantive references to economic growth—the references that commit the government to pursue growth—requires more digging. This is because most references to “economic growth” in the code—about 133, by my count—don’t create binding and enforceable law by themselves.

Statements of purpose, declaration of policies, and findings—elements like these help to clarify the purpose of laws, but they don’t enact the law. For example, Section 1801 of Title 19 declares that it is the purpose of the Trade Expansion Program to “stimulate the economic growth of the United States…” To be sure, this embeds a pro-growth tone in the Code – but unless we understand how this policy will “stimulate the economic growth,” we won’t know how to amend this part of the code to accomplish more sustainable trade goals.

To get at the “how” of the law, we need to delve into the binding portions of the bill—the ones that spell out the requirements, prohibitions, enforcement mechanisms, and oversight provisions that operationalize the broader purpose of a law. For example, Section 1017 of Title 42 requires the Secretary of Energy to report on how locating a nuclear repository in Yucca Mountain might impact economic growth. The bill spells out who will write the report, for whom, by when, and for what purpose. This type of language “enacts” economic growth as a priority of the Federal government.

Such binding references to “economic growth” are plentiful, encompassing 73 mentions across 16 of the 54 titles comprising the Code. By comparison, wellbeing is found only twelve times, labor rights nine times, and gun safety twice. Let’s take a look at how some of these references show up in—and shape—widely different domains of federal policy.

| Title | Number of Binding References to “Economic Growth” |

|

| Title 22 | Foreign Relations and Intercourse | 31 |

| Title 42 | The Public Health and Welfare | 9 |

| Title 2 | The Congress | 6 |

| Title 48 | Territories and Insular Possessions | 5 |

| Title 19 | Customs Duties | 4 |

| Title 29 | Labor | 4 |

| Title 12 | Banks and Banking | 3 |

| Title 16 | Conservation | 2 |

| Title 31 | Money and Finance | 2 |

| Title 49 | Transportation | 1 |

| Title 15 | Commerce and Trade | 1 |

| Title 8 | Aliens and Nationality | 1 |

| Title 7 | Agriculture | 1 |

| Title 33 | Navigation and Navigable Waters | 1 |

| Title 25 | Indians | 1 |

| Title 40 | Public Buildings, Property, and Works | 1 |

| Total | 73 |

Content Analysis

Numerically, the term “economic growth” appears most often within titles relating to foreign relations, customs, and trade. This is partly due to the sheer number of separate bills and treaties that fall under these categories. These references can often be found in the context of requirements for foreign nations to receive American assistance. For example, Section 2395 of Title 22 insists that any country “eligible to receive cancellation of debt under this section” can do so only if they have taken “…steps to…promote broad-scale economic growth…”

Similarly, Chapter 32 of Title 22 (Foreign Assistance) requires the president to “take appropriate steps to discourage actions which might “impair” the “…stable economic growth and development” of countries receiving American assistance. Such references embed “economic growth” as a priority for both the USA and foreign nations who hope to receive our aid.

“Economic growth” also appears frequently in bills related to public health – often as a way of qualifying or restraining efforts to protect the environment. Section 7612 of Title 42 requires the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency to describe the effects of air pollution regulation on “economic growth.”

“Economic growth” is also found in statements of purpose, as when Chapter 91 of Title 42 declares that the “National Energy Conservation Policy” is to “conserve nonrenewable energy resources produced in this Nation and elsewhere, without inhibiting beneficial economic growth.” Here again, economic growth is prioritized over other federal policy objectives.

Parts of the code related to banking and finance also contain significant references to economic growth. Section 1811 of Title 12 asks the Secretary of the Federal Deposit Insurance System to change financial regulations to better “promote economic growth.” Section 5330 of the same title insists that the Financial Stability Oversight Council “take costs to long-term growth into account” when developing stricter financial regulations.

Are you beginning to see a pattern?

The olive branches symbolize peace and prosperity facilitated by economic growth, says U.S. law. (NCUA)

“Economic growth” appears in some strange, surprising places as well. The notes of Section 1752 of Title 12 reference an executive order by President Trump specifying that the olive branch held by the eagle in the National Credit Union Administration’s seal “symbolizes the peace and prosperity facilitated by…economic growth…” OK, then.

The notes of Section 330 of Title 15 reference the National Weather Modification Policy Act of 1976, which calls for a study on whether “deliberate weather modification” could be used to “decrease the adverse impact of weather” on economic growth.

What sticks out, however, is how often references to “economic growth” are used to restrict democratic policymaking in order to accomplish this narrow—and increasingly destructive—goal. Nowhere is this clearer than in Title 48, entitled “Territories and Insular Possessions.” Section 2141 requires any fiscal plan developed by The Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico (otherwise known as “La Junta”) to “provide for capital expenditures and investments necessary to promote economic growth.” Not expenditures for health, or wellbeing, or sustainability, but growth. This diktat is nothing less than an environmental death-sentence for Puerto Rico. But it is only formalizing the growth obsession that already drives our economy.

Conclusion

Returning to our opening question, imagine framing U.S. laws differently. Currently, Section 1105 of Title 31 requires the Director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to deliver a report analyzing the impact of federal regulation on “economic growth.” If legislators replaced that phrase with “economic stability,” what would result?

In the steady state economy, we’d see fewer of these behemoths. (PXFuel)

On one hand, possibly little. Altering explicit references to “economic growth” (and its synonyms) within the U.S. Code would far from guarantee a steady state economy. After all, most federal policies accelerating growth do not mention growth at all. To reform them requires us to go past labels and identify the legal requirements that enact economic expansion in the USA, and fundamentally modify them.

On the other hand, changing our language could mean a lot. Forcing the OMB to monitor economic stability instead of economic growth, for example, embeds an entirely new criterion for judging federal policy within the Code. We’ll be able to leverage the resources of this office to understand precisely how our laws are blowing us off the steady-state course, and we’d understand better how to correct them.

Ultimately, CASSE’s goal is to uproot all explicit and implicit commitments to growth hidden in the Code (and in federal rules more broadly). By breaking these shackles and embedding “economic stability” instead as the law of the land, we can go a long way towards building the steady state economy in the USA.

Daniel Wortel-London is CASSE’s Policy Specialist.

I have been saying for years that we should change that clause in nearly every corporate charter (including nonprofits) that they must grow or else. I do not think that is a f

Great information, but not unexpected. When you think of economic growth in terms of the energy or conservation sectors it why as a career energy efficiency engineer in the USA, I learned early on not to talk about energy savings, that the term “conservation” was a dirty word akin to communism, and only speak in terms of money saved in energy spend that could mean more money could be devoted to growth and beating out competitors. I’m afraid competition and the zero sum game is so ingrained across the world (and especially in the USA), which nation would start with a steady state economy when it would mean you may likely lose out to competing nations. I’m also afraid a great term like economic stability would simply be hijacked to mean growth, it would have to be very tightly defined in a legal sense.

This is akin to when I first started my career and if I used the term conservation, I got the “so we’ll need to wear our coats indoors?” response. I think the first hurdle is not to change the legislation, but to change the perception that competition and growth are best for all of us, and if not all of us, some of us. We first either have to convince those who have the power and wealth to change, or spread the wealth and power evenly and convince most people to change. I wish I had the answers.

This article proves that the other side is winning the war of words, and that language counts and engrains itself in consciousness and law. To counteract the unfair playing field in the USA, I believe (naively?) that we can fight to gain an edge by collecting and repeating the critiques against growth that have come from respected American public figures. We could start, for example, with (A) Henry David Thoreau &(B) Robert F Kennedy. (A) “If a man walk in the woods for love of them half of each day, he is in danger of being regarded as a loafer; but if he spends his whole day as a speculator, shearing off those woods and making earth bald before her time, he is esteemed an industrious and enterprising citizen.” (B) GDP “measures everything excecpt that which is worthwhile.”

I do much work in the environmental community and even committed environmentalists have a hard time grasping the end of growth and its implications. it is truly engrained deep into the American psyche, but we must persist.

I love it when I see people doing practical work on what needs to be done.

In 1999, the Board of Supervisors of Santa Cruz County unanimously passed County Code Title 16, Chapter 16.92 Environmental Principles and Policies to Guide County Government. Look at the Purposes of this amazing prescient legislation (below) and be sure to read 16.92.010(B)(5) and (6) —

16.92.010 Purposes.

(B) To direct County government to utilize its powers and resources to endeavor to accomplish all of the following:

(1) To provide for the more efficient use of renewable energy and recycled resources;

(2) To protect biological diversity and human health, through protection and restoration of the environment;

(3) To encourage agricultural practices which are protective of the natural environment and human health;

(4) To promote and encourage economic development strategies in Santa Cruz County which are consistent with both environmental protection and environmental restoration, and which will help create a local economy based on the use of renewable resources;

(5) To ensure that future growth and development in Santa Cruz County recognizes and respects the natural limits and carrying capacity of the Santa Cruz County environment; and

(6) To instruct Santa Cruz County government to take actions, locally, which can help reverse, reduce and eliminate those actions and practices which are contributing to environmental crises which are global in scope.

(C) To urge all the elected officials who represent the people of Santa Cruz County, at the city, State and Federal levels of government, to take any and all actions in their power which can assist in the protection and restoration of the environment of Santa Cruz County, and which can help reverse, reduce and eliminate those actions and practices which are contributing to environmental crises which are global in scope.

We’re working to see this is re-codified.

Jean this is excellent stuff, especially the 5th clause with mention of natural limits. Best wishes getting this renewed, it is exactly what our civilization needs.

Thank you Daniel for this work. All I can ask is: how can we individuals help?

If there’s anything in particular that we can do, however small or indirect, please let us know.