“I Know You’re Malthusian, But What Am I?”

by John Mirisch

Times are evidently rough for our natalist, growthmaniac friends.

More people than ever are questioning their agenda of increasing the planet’s population beyond the current 8 billion people (double the level of less than fifty years ago) in the name of “progress” and profit. Yet the growthmaniacs’ only response to anyone who links human population and ecological overshoot is to scream “Malthus!” at the top of their lungs (although some Marvel fanboy growthmaniacs have been known to respond “Thanos!” instead).

Their latest attempt at climate-change revisionism and denial of ecological overshoot is an article in the neoliberal magazine The Atlantic entitled “The Malthusians are Back.” It takes shots at anyone critical of ongoing population growth, such as Harvard professor and climate researcher Naomi Oreskes, who recently wrote an op-ed in Scientific American with the straightforward title, “Eight Billion People in the World Is a Crisis, Not an Achievement.” Oreskes’s subtitle deftly underscores the point: “More people will not solve the problem of too many people.”

Good point. (Mark Klotz, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The main thrust of The Atlantic’s swing at the Oreskes op-ed is to assign guilt by association: Bad people, like eugenicists, once railed against overpopulation, so anyone concerned with overpopulation today is “joining an ugly tradition.” Rather than engage with modern, science-based concerns about the environmental impact of overpopulation and the human footprint, the authors seem to take great pleasure in detailing the “ugly tradition,” as if that were enough to dismiss the logic underlying concerns about growth. It’s as if Cargill Meat Solutions were to trash vegetarianism because of its “dark history”: After all, Genghis Khan, Hitler, Stalin, Pol Pot, and Charles Manson were all vegetarians.

Shills Gonna Shill

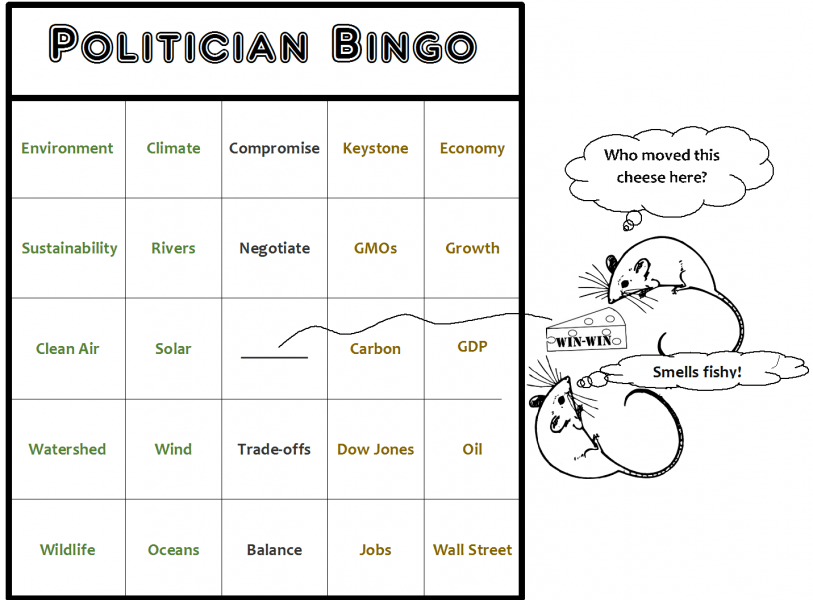

A red flag signaling the growth addicts’ lack of concern with science, and their utter desperation to find a hook, is their quoting of Urban Growth Machine propagandist Jerusalem Demsas as if she were Immanuel Kant: “Enough with the innuendo: If overpopulation is the hill you want to die on, then you’ve got to defend the implications.” What implications? This: If you’re concerned about overpopulation, then you hate people. It’s right there in the title of Demsas’s quoted article, “The people who hate people.” And: If you’re concerned about overpopulation, then you must support eugenics—or worse. The categorical imperative of Demsas and her colleagues at The Atlantic can pretty much be reduced to this: If you like people, then more humans is always a good thing.

Of course, if you support a system of capitalism predicated on the need for growth, “more” is a must. It’s hardly a surprise that Demsas and her neoliberal buddies consistently invoke the WIMBY (Wall St. In My Backyard) credo of “build, build, build,” a corollary, of course, of “grow, grow, grow.” They cite climate change as a pretext for forced density, while ignoring the core cause of climate change—population growth—which itself is a subset of ecological overshoot.

Pack ‘em in. (杨志强Zhiqiang, Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 2.5)

Let’s ignore, for a minute, that the Atlantic authors use “Malthus” as a pejorative; a code word meant to discredit, and thus ignore, the points made by Professor Oreskes and others. Let’s ignore that they are simply wrong in invoking Malthus and in their use of the adjective “Malthusian” (or neo-Malthusian). Let’s move on from the Malthus straw man.

Early in the “Malthusians” article, the authors write, “In recent years, many climate advocates have emphasized human population itself—as opposed to related factors such as consumption and technology—as the driving force behind environmental destruction.” To suggest we talk about consumption without talking about population—that is, consumers—is absurd. They are two sides of the same coin. We need to talk about the two together because the ingredients of humanity’s environmental impact are two interrelated variables: per capita consumption (or throughput) and the number of consumers (or human beings, i.e., population). To reduce overall consumption (and therefore, environmental impact), you can reduce per capita consumption, the number of consumers, or both.

No Free Lunch

Technological efficiencies can potentially reduce the per capita impact of consumption, but we cannot “decouple” economic growth from environmental impact. In other words, there is no such thing as “guilt-free” energy and there are no free lunches. The authors of the Atlantic article, Alex Trembath and Vijaya Ramachandran, however, would be the last to acknowledge that decoupling is a myth. You see, Trembath and Ramachandran both work for the ecomodernist Breakthrough Institute, whose “manifesto,” according to writer T.J. Demos,

“is basically an apology for nuclear energy that allows its authors to reassert the imperative of economic development, as if such an energy system will have no impact on Earth systems (counter to recent experience in Fukushima). What’s striking is that there’s no mention of social justice and democratic politics in this account, no acknowledgement of the fact that big technologies like nuclear fusion reinforce centralized power, the military-industrial complex, and the inequalities of corporate globalization, rather than the distributed self-sufficient economies and egalitarian local governance that tend to accompany renewable energy paradigms.”

Later in the Atlantic article, Trembath and Ramachandran write that those concerned with overpopulation “have tended to emphasize humanity’s destruction of nature” instead of “focusing on famine” as Malthus and others did, and they note that starvation has been forestalled by advances in agricultural productivity. The implication is that technology will always serve up solutions and that the next “Green Revolution” will stave off the starvation of eight billion people and more. A further implication: As long as human mouths can be fed, “humanity’s destruction of nature” isn’t such a big deal.

For those who value nature and care about humanity’s role in its destruction, these unrepentant human supremacists implicitly posit a Demsasian proposition: If you’re concerned about humanity’s role in the destruction of nature, you think people are pollution, and you’re a person who hates people. Using this logic, climate deniers could similarly argue, “If you think climate change is the result of human activity, you’re a person who hates people.”

So, to clarify: Human beings aren’t “pollution.” But humans cause pollution (in addition to depleting limited resources and destroying other life on the planet). We’d better not ignore the ultimate cause of the problems we’re trying to fix, if we’re serious about fixing them.

On the technology front, the Atlantic ecomodernists, after their reference to the Green Revolution, seem to imply that human technology is up to any challenge, even in defiance of the laws of thermodynamics. Indeed, one can imagine them exclaiming: There are no such things as limits to growth because there are no limits on the human capacity for intelligence, imagination, and wonder. OK, so it was really Ronald Reagan who said it first, but you get the point. As environmental studies professor Jeremy Caradonna wrote about the ecomodernist manifesto: “Far from being an ecological statement of principles, the Manifesto merely rehashes the naïve belief that technology will save us and that human ingenuity can never fail.”

PonziPalooza

While the authors acknowledge that global population is “expected to peak and decline later this century,” they see this as a problem, not a course correction or opportunity. In a world of eight billion people, the demographic challenge, they claim, is “underpopulation.” Countries with declining birthrates need more people to generate “economic growth” and support an aging population. If this dynamic isn’t the definition of a Ponzi scheme, I’m not sure what is. And while the likely coming population decline is not due to “war, famine or disease,” as Trembath and Ramachandran admit, neither is it due to eugenics, forced sterilizations, or coercive birth control methods.

Plenty of room for more. (JDBenthien via Pixabay)

Female empowerment and availability of contraception have been key to population stabilization in many countries, but the Atlantic authors are singularly dismissive of it. They write, “Access to education—in general, or to sex ed and ‘population studies’ in particular—is certainly preferable to Vogt’s forced sterilization. But what about solutions to environmental decline that emphasize better growth instead of slower growth? Solutions such as modern energy infrastructure, high-productivity agriculture, and access to global markets?”

Ah, yes: Let the Ponzi scheme continue. Buttress industrial economies by borrowing ever more deeply from nature, postponing further our reckoning with overshoot. Meanwhile, postponement only worsens the consequences of the inevitable crash. If you care at all about coming generations—if you love people—you should tremble at this future.

Perhaps Trembath and Ramachandran are fans of Louis XV. At any rate, it seems they have never heard of the Jevons paradox. It seems that they deny, with Reaganesque optimism, the reality of limits to growth on a finite planet with depleted resources. It seems they don’t care about other species. It seems they aren’t interested in ensuring that women and families have access to education and contraception and that women decide for themselves the family size that is best for them.

The growthmaniacs frequently cite the Chinese “one-child” policy as a “Malthusian” example of anti-human coercion. Yet China, itself susceptible to the allure of Ponzi schemes, is now panicking and moving toward a “three-child” policy. The incentives and blandishments for women to have more children aren’t really working there, any more than they are in countries like Sweden. Swedish policies make it easier (than in the USA) for families to have children, with benefits such as free preschool, subsidized childcare, direct child subsidies, paid parental leave, and the right to miss work with pay to take care of sick children. These policies allow people greater choice, and with that choice, people are opting for smaller families.

Families have interests beyond making and rearing babies, despite the incentives in countries like Sweden. In attacking groups like Planned Parenthood, the Atlantic’s “anti-Malthusians” seem to be doing little more than making common cause with natalists and anti-abortionists of the American far right. They seem to think you’re a “person who hates people” if you support free access to contraception and if you’re pro-choice.

The Real Eugenicists

Trembath and Ramachandran’s attempts to link those concerned about planetary overpopulation with eugenics is a red herring. The biggest eugenics threat today comes not from those concerned about overpopulation, but from those complaining of underpopulation, especially from an extreme wing of “effective altruists” who have created their own pronatalist movement. Not surprisingly, these modern-day eugenicists, says writer Rachel Donald, come from “Silicon Valley, where upper middle class technologists believe it is their duty to repopulate the planet with more upper middle class white technologists. Simone and Michael Collins are leading the charge, out to have 10 children as quickly as possible, who they will indoctrinate to each have 10 of their own, and so on. They hope that, within 11 generations, their genetic legacy will outnumber the current human population.”

Trembath himself is full of praise for the “effective altruists.” In a series of astonishingly error-filled assertions, he writes:

“Your typical ecomodernist and effective altruist each believe in the liberatory power of science and technology. They are both pro-growth, recognizing the robust relationship between economic growth and human freedom, expanding circles of empathy, democratic governance, improved social and public health outcomes, and even ecological sustainability. Notably, every effective altruist I can recall discussing the matter with is pro-nuclear, or at least not reflexively anti-nuclear. That is usually a litmus test for broader pro-abundance views, which effective altruists and ecomodernists both tend to espouse. Ecomodernists and effective altruists both attempt an evidence-based analytical rigor, in contrast to the more myopic, romantic, and utopian frameworks they are working to displace.”

It’s an interesting image Trembath has of himself and his fellow travelers, and it’s not at all hard to look at his Atlantic piece as a defense of his “effective altruist” buddies’ pronatalist movement. To others, though, their pronatalist movement may not look all that appealing. To Donald: “The movement looks an awful lot like white supremacy dressed up as techno-utopian utilitarianism.” Indeed. It’s fairly easy to understand why Trembath would want to talk about “Malthusian eugenicists” of a half century ago to distract from the fact that “these ‘effective altruists’ are obsessed with saving their skin.” by “panic-breeding white babies.”

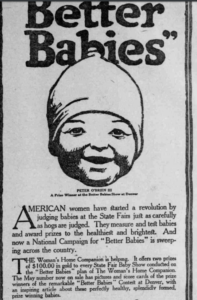

Every day, in every way, better and better. (The Morning Oregonian)

Fortunately for humanity, the narcissistic, solipsistic pronatalists, who as Donald writes, “do not believe themselves accountable for the world today,” but “believe themselves to be the gods of tomorrow” seem to be but a fringe cult of sociopaths. As noted, for most of the rest of the world, incentives to coax a return to the bad old days, when women were baby factories, don’t work. If anything, the next step for authoritarian countries like China could be to use coercive policies to get their populations to breed.

Funny, there doesn’t seem to be a lot of concern from the ecomodernist growthmaniacs about coercive natalist policies. I wonder why. I guess if you force people to have more babies, you really are a “person who loves people.” You certainly are a person who loves the idea of more consumers (and perhaps laborers) for a system of expansive authoritarian capitalism that is based on what Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg calls “fairy tales of eternal economic growth.” Keeping fairy tales alive seems to be the main concern of the Atlantic’s consumer lovers, er, “people lovers.”

Respecting the Law

Whether we like it or not, we live in a finite world with limited resources. As the global population increases, more people will consume and shrink the resource pie, no matter how it’s sliced. And whether we like it or not, the laws of thermodynamics apply to economics as well as to the planet.

No future with overshoot. (Alex Fedini, Pixabay)

People who deny ecological overshoot, who refuse to accept the role that human consumption plays in the degradation of our planet, and who knowingly ignore the role of population growth in threatening humanity and the millions of species we share the planet with—these are people who seem entirely indifferent to nature. And they actively advocate staking the future of humanity and our fellow species on Ponzi schemes of growth.

Call me “Malthusian” (or “Thanosian”) if it makes you feel better and if that’s all you’ve got (even if you aren’t sure what Malthusian means). Malthus, schmalthus. Name calling won’t stop me from talking about population or why we need a steady state economy to replace the fairy tales of eternal economic and population growth. Nor should the threat of name calling prevent rational people who care about logic, reason, humanity, and the planet itself from engaging in frank discussions on population and ecological overshoot.

People (as well as dark-money and corporate-funded AstroTurf groups) who claim to “love people” seem to be more in love with corporate profits, ROI, and money than anything else. As indicated by the persistence of growthmaniacs who huckster Ponzi schemes like so many snake-oil salesmen, there may be no limits to greed. But there are very real planetary limits to growth.

Simply stated, Ponzi schemes, whether ecological or economic, can never be the pathway to abundance or sustainability.

John Mirisch was elected to the Beverly Hills City Council in 2009 and served three terms as mayor. He now serves as a garden-variety councilmember.

Maybe people don’t understand what the word “Finite” means? Why people think they can infinitely reproduce the human species is a mystery. Is it because if one does not have to directly bear the costs of ones actions, it is easier to continue those actions? It is hard to believe costs now pushed onto the environment, (thus not directly impacting humans) will not eventually impact humans directly. And not in a good way. The idea that “technology” can somehow mitigate all adverse population repercussions seems unrealistic. Guess time will tell.

Amen! Thank you for writing this! I didn’t read the article you refer to, and I certainly don’t want to. I would certainly get as riled up as you did, and don’t need the stress.

I looked at the article by Alex Trembath and Vijaya Ramachandran. You don’t critique worriers about overpopulation with just wordiness and in-vogue, button-pushing epithets. In their article, there’s a total absence of any demographic numbers. This is a problem with a lot of pseudo-intellectualists who are literate, consequently wordy, and overconfident in their wordiness. Either they’re innumerate, or they’re too lazy to be numerate.

I’m an Indian. India’s population is set to surpass China’s very soon. I share all the concerns of the author. And just for the record, I don’t hate fellow humans.

One of Malthus’s oversights is he did not anticipate the profound impacts that digging up stored fossil energy would have on everything (including food production and distribution). In 1859, when the first oil well was dug in Titusville, PA, world population was 1.2 billion. Now that fossil energy has peaked, feeding everyone on the fossil downslope rarely gets serious consideration in terms of logistics (or psychology).

Martin Luther King even warned about the perils of overpopulation, when we were at 3.5 billion people.

Growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of the cancer cell.

http://www.peakchoice.org/peak-population.html

A good read. I expect we are mainly preaching to the converted on this site. A steady state is the objective. If we can get organised, do say two thirds of our current consumption, theres a good opportunity for a reasonably healthy planet. The question we have toanswer is how can we transition away from a growth model to a steady state model. Change can be quick and viral if and when people see a solution they believe in, Microsoft tech dominance started in Bill Gates garage a few decades ago, Jeff Bezos doing something similar. We need to speed up consumer support for commonly owned cooperatives, these suppliers replacing the growth model, and competing to deliver sustainable solutions.

I will do my best to share this article. Impeccable argumentation and exquisite style. The only thing I can add is that the most harmful part of the population equation is the spiking population of billionaires. The carbon footprint of space explorers Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson is greater than the entire population of entire continents. If they could make it to Mars and just stay there, we’d be well on our way to dealing with overpopulation here on earth.

All I can add is that I’ve seen the Silicon Valley phenomenon. What never fails to astonish me is how people who are at least fairly intelligent just can’t think through likely outcomes and consequences, with all the ripple effects. E.g: if A will cause B, what will B cause? Thing C is stable, but will more/less B change that? And so on. Thinking is hard :)

It’s probably why the vast majority of Silicon Valley startups fail. Treating our planet like an interesting startup venture – “hey, if this one fails, we’ll just do another one” – is not wise, to say the least.

Here’s a fact, not a theory, thought, or idea. The famous Ehrlich and Holdren I ≈ PAT identity can be rewritten as F = PAR, where F = footprint; P = population; A = affluence (GDP/population); R = resource or footprint intensity of GDP (F/GDP).

That is, F = P x GDP/P x F/GDP (a true equation, not an identity)

Globally, over the past fifty years, F has approximately doubled (2x); P has approximately doubled (2x); A has approximately doubled (2x); R has approximately halved (0.5). Therefore, R cancels out A, meaning that the doubling of F, which is now 70% above global biocapacity (ecologically unsustainable), can be attributed to the doubling of population (2 = 2 x 2 x 0.5). It means that if global population was the same as it was fifty years ago, the global footprint would be approximately half of what it currently is (what it was fifty years ago) and less than global biocapacity (ecologically sustainable) (1 = 1 x 2 x 0.5).

Anyone who denies that population growth is a problem is a denialist who belongs in the same camp as climate change denialists. They also need to return to school to learn multiplication.

Guilt by association: In Australia, where population growth is fueled by net migration, anyone who calls for reductions in the immigration intake on ecological grounds is immediately labelled ‘racist’ because some extreme right-wing groups call for a cut in immigration, usually on ethnic grounds.

Population growth has been the main driver of environmental damage over the past century. I gave a presentation at the COP-23 climate change conference in Bonn in 2017 and was almost chased out of the room for raising the issue of excessive population.

Spot on, Philip. I see the strawman argument about xenophobia and immigration all the time here in California. What sort of helps, I think, is to realize that this is meant to drag the discussion into the gutter. The key is to maintain a polite calm demeanor, and gently emphasize “I hear your concerns, but the characteristics of the people here are not really salient. This is a math problem, a problem of numbers, nothing more and nothing less.”

@philiplawn, thanks for the interesting comment. I like people, I watched a family of 3 recently, beautiful kids full of fun and devilment. Life is so special and it’s great to see. Population growth , for me, positively framed is a challenge, not a problem. In traffic you are somebody else’s congestion. In population you shouldn’t be seen as a problem. Back to the challenge. It’s encouraging to note that footprint intensity of gdp has halved. Its clear folly to activrey encourage greater numbers and unreasonable to label others as problems. Typically global families are of 2 kids, better health are with people surviving longer is what I understand is pushing up the growth. A big part of the solution lies in discouraging profit driven growth while minimising the footprint intensity. A world where all roofs are solar, wind generators are widespread. Where products have long lives, are repairable and easily truly recyclable. Food is a challenge. It should not only be labelled for the price, and potential harm of salt and sugar, the environmental cost should also be quantified so that we can all eat sustainably. If we did this, drove small cars, had cold showers, ( they’re a buzz) and one for you, didn’t cut the lawn, maybe we can half the R one more time.

I don’t think anything I said suggested I don’t like people. In fact, I like people so much I’d like to see humankind limit the number of people currently alive to maximise the number of people who will get the chance to live. There’s little doubt that, by depleting natural capital to the extent that it has, humankind has already reduced the number of people who will ever live.

Nor did I say that any particular person or group of similar-type people are a problem. I consider myself to be as much of a problem as anyone else, perhaps more so because I’m Australian and although I do my best to limit wasteful consumption, I probably have a greater environmental impact than the average global citizen. That’s why I talked about the population issue in the context of the F = PAR equation. Per capita consumption needs to be addressed along with population numbers.

Frame the population issue as a challenge rather than a problem if you like – perhaps call it an opportunity – but it doesn’t alter the stark reality of the situation and the fact that population numbers need to be contained to help address the impending ecological crisis.

@philiplawn, Apologies for any discomfort, no ill will intended. Thanks for your reply, Your insightful formula shows population having doubled and R the footprint intensity of gdp being halved. My understanding is that population is projected to peak at 9 to 10 billion, with a great deal of error margin. If projections on population are let run as expected the impact can be offset by reducing our footprint, some basic care of the environment.There is so much improvement that can be made with a little more thought by everyone, no big effort needed. Less emissions, less resource wasting and without any real pain and some satisfaction that R number can be halved again. Its abhorrent to me to have gdp growers aiming to increase population in the name of growth, much as it also seems wrong to me to actively interfere to discourage family size. In a healthy fair society families will righsize themselves is my expectation. In an unhealthy world of unfair wealth distribution, low opportunity for personal betterment, where woman are not equal, the population numbers may end up on the worrying higher range. 16bn a worst case prediction. The true worry is that GDP growth with ongoing unfair distribution of the spoils, may take us there.. Population growth would be a symptom of the problem not the cause. We need to get off the growth model, onto competing cooperatives, competing to deliver sustainable

solutions, encouraged by consumers sharing their visible reputations.

Here’s another fact. I was born in 1964 when there were 3.25 billion people on Earth. That’s 41% of the world’s population in 2022. Even if we had lived our lives as we did in 2022 – meaning the global per capita Ecological Footprint (EF) would have been as it was in 2022 – if there had still been 3.25 billion people in 2022, the global EF would have been 41% of what it was in 2022. The global EF would have been less than global Biocapacity (BC) – the global economy would have been smaller than its maximum sustainable scale. We would have been partying on New Year’s Eve like never before. Population growth is one of the major drivers, if not the number one driver of the global EF.

Reducing the EF/GDP ratio won’t be as easy or as inexpensive as many people think. The halving of the ratio over the past half century has involved the picking a lot of low-hanging fruit – many of the relatively easy and cheap options have already been adopted. I’m not suggesting that we give up on reducing the EF/GDP ratio. We need to address the per capita consumption and population issues if we are to have any chance of bringing the global EF back within global BC. That said, our need to go further with measures to reduce the EF/GDP ratio, which will entail the use of resources (e.g., establishing ‘green’ infrastructure), will be costly, in part because of our failure to deal with population growth in the past. And it will only be harder and most costly if we continue to ignore the population issue.

I find it so disturbing that a shocking proportion of the people developing AI have such a staggering level of Natural Stupidity to not recognize the fundamental and obvious truths in this piece. This piece has provided me with the best explanation for Elon Musk’s staggeringly sociopathic insistence on a growthing population:

“The movement looks an awful lot like white supremacy dressed up as techno-utopian utilitarianism.”

Excellent article! Anyone that has taken a physics course, knows that matter cannot be CREATED or destroyed. We can’t create any “more” with technology. The earth is indeed finite and there is only ONE pie that is being divided. The division is massively unequal (the 1 percenters getting the most) leaving the other species and people that are in dire poverty with tiny slivers of the pie, if anything at all.

“No ‘BAU’?

‘Most’ ‘economic thinking’ is ‘short run’ and ‘redundant’? ‘It’ ignores the ‘supply side’? ‘Growth’ {and ‘civilisation’} depends upon ‘cheap’ F.F. – those so called ‘halcyon days’ are ‘over’. ?

“The crisis now unfolding, however, is entirely different to the 1970s in one crucial respect… The 1970s crisis was largely artificial. When all is said and done, the oil shock was nothing more than the emerging OPEC cartel asserting its newfound leverage following the peak of continental US oil production. There was no shortage of oil any more than the three-day-week had been caused by coal shortages. Even as we struggle to reimagine the 1970s in an attempt to understand the current situation, the only people on Earth today who can even begin to imagine the economic and social horrors that await western populations are the survivors of the 1980s famine in Ethiopia, the hyperinflation in 1990s Zimbabwe, or, ironically, the Russians who survived the collapse of the Soviet Union.” ?

https://consciousnessofsheep.co.uk/2022/07/01/bigger-than-you-can-imagine/

1/3

I’m late to the party. (I won’t claim better late than never!)

It’s important, I think, to look at who is speaking.

In the case of the Atlantic article, it’s the Breakthrough Institute (BTI), co-founded by Ted Nordhaus (coincidentally nephew of the economist William Nordhaus https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2018/nordhaus/facts/) whose snarky, I-am-the-light, growth-is-good opinions I first encountered in the book he co-wrote with Michael Shellenberger (also co-founder of BTI), in the early noughts, entitled “Break Through: From the Death of Environmentalism to the Politics of Possibility”. (At the time, I submitted an appropriately worded 2-star review to Amazon.com). The authors of the referenced Atlantic piece are, apparently, simply parroting the belittling style of their leader.

Intention is so hard to discern from a distance, but I do sometimes wonder if the likes of Nordhaus, Shellenberger, Patrick Moore (co-founder of Greenpeace), and others similarly re-born, having internalized a view of a hopelessly doomed future, are simply trying to have some fun and finance their remaining time. Who knows?

Something that struck me – perhaps overly much — in this CASSE opinion, was the author’s reference, in the phrase “forced density”, to the stable population…

cont…

2/2

…example of Beverly Hills and the ongoing effort to maintain it, as is, and – so far, so good — fend off redevelopment and densification. (I particularly appreciated his inclusion – in his self-authored reference — of some basic demographic data, so we know the quarter is not populated solely by the rich and famous.) It seemed out of place, in this broader context of global impacts, because it takes a very limited view of the world; as if what is important is only the look and feel of one’s own patch; as if the conglomeration that spread out from the early precincts of LA County, including Beverly Hills, was of no consequence or, minimally, had no real connection to the urban design of his urban oasis. Then, of course, is the existential question, brought into sharp relief with the decades-long drought – and the recent partial reprieve — in the Southwest, about whether the deserts should have ever been settled.

Population increase in cities is not solely the result of increased global population; it is also the result of rural to urban migration itself resulting, in part, from technological change and financial market interest in agriculture and the lands which support it.

The ecological footprint of Beverly Hills, stable as its population has been for decades, is, I expect, rather high (increased since 1970?), even by comparison to average numbers for the USA which, of course, cannot be sustained; certainly not if we believe in an equitable quality of life – for humans… and everything else — across the globe.

If we are seeking a 360-degree view, then it behooves us to not stop at 350, and pay no attention to inconvenient 10 that hide behind the curtain.

cont…

3/3

Aside from that, and some other quibbles (inconsistency between seeing efficiencies of net positive early, but later referencing Jevons, which can lead to net negative), there is much to agree with. In my limited reading, anything from BTI is deserving of a robust riposte.

I wonder if the population consideration is just one of those topics which can’t be mentioned in isolated sound bites; it is so easily weaponized without have contextual, if dull, guardrails (ropes around the ring?).

Canada, where I live, is in the process of increasing immigration by ½ million per year for coming years, presumably to keep the economic system, as it is, afloat in the face of the wave of retiring boomers who see a need to remain on the pension continuation plan. We are also trying to have our cake and eat it to, as is the USA. Continuing to supplement fossil supply, for example, and relying on future tech-salvationism rather than acting.

There’s yet another, new book I’ve just cracked the cover on which may be of interest to some. In the early pages it is acknowledging this issue of population and the associated baggage. It was written by York University (Toronto) professor emeritus Peter Victor https://newsociety.ca/books/e/escape-from-overshoot?sitedomain=ca, who also happened to pen a bio of Herman Daly. https://www.pvictor.com/herman-daly-biography-reviews He was the founding president of the Canadian Society of Ecological Economics and is a past-president of the Royal Canadian Institute for Science.