Putin the Practical Wants Ukraine Grain

by Brian Czech

Pundits, think tanks, and politicians are asking, “What does Putin want with Ukraine?” If you’re familiar with Ukraine’s flag—especially the bottom half—you’re halfway to the answer.

Putin: inscrutable yet exuding a cynical practicality. (CC BY-SA 2.0, Global Panorama)

But let’s start with the conventional wisdom. Yes, Putin wants to pressure the West into preventing Ukraine from joining NATO, thereby keeping the alliance off Russia’s doorstep. Russia’s natural gas transmission to Europe would be a lot more profitable if they didn’t have to pipe the gas through tariff-charging Ukraine, too. Hundreds of miles of shoreline on the Sea of Azov with its rich sturgeon fishery doesn’t hurt, either (even with Crimea already grabbed).

There’s also the bluntest geographic reality of all: Ukraine is one of the largest countries in the world that could conceivably be stolen by a menacing neighbor.

No one knows for sure what’s on Putin’s mind, but it’s clear what the Western press has overlooked: those amber waves of Ukraine grain!

Ukraine’s Flag

Recently I had the opportunity of interviewing Chris Matthews for the The Steady Stater podcast. When I asked him for recommendations on advancing the steady state economy, he quickly honed in on the paucity of geographic knowledge among Americans. His point is well-taken: How can we understand limits to growth without a good grasp of geography?

It’s not just about place names and borders; far from it. Merely recognizing the military implications of coastlines, mountain ranges, and rivers doesn’t cut it either. What’s crucial for an understanding of everything from poultry to politics is ecological and economic geography. And, in the 21st century, climate change must be taken into account as well.

Ukraine: the land and its flag. (sunnylapin, Alex Maisuradze)

Now, is there a flag in the world more starkly reflecting the ecological and economic geography of a nation than Ukraine’s? Sweeping landscapes of wheat under sunny summer skies: that’s what makes Ukraine the breadbasket of Europe!

Ukraine has approximately a third of the world’s black soil; that is, the coveted “chernozem,” highly fertile and full of humus. This soil is so valuable that, during the transition from Soviet kolkhozy (collective farms) to Ukrainian agribusiness, nearly a billion dollar black market (annually in 2022 dollars) thrived by the truckload. Ukraine’s climate is similar to that of Kansas, the heart of the American breadbasket. Finally, the topography of Ukraine is neither too flat to cause saturation problems nor too rolling to cause cultivation problems, although soil erosion is a threat given the black-market excavation of chernozem and the industrialization of agriculture.

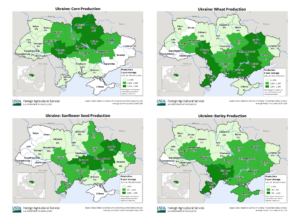

What’s the bottom line of all this ecological geography? For starters, two-thirds of Ukrainian land is farmed. Eastern Ukraine, especially, is grain-crop heaven. Ukraine is the fifth-largest wheat exporter in the world. It’s the fourth-largest exporter of corn and rye, and third-largest of barley. It’s by far the largest exporter of highly profitable sunflower oil.

Ukraine also produces prolific crops of soybeans, potatoes, beets, legumes, fruits, and a variety of vegetables. It refines some of its production into sugars, meal, vegetable oils, and honey. The primary meat products are beef, pork, veal, and chicken. Dairy production waxes and wanes, largely in response to superseding agribusiness trends.

By far, the agricultural and economic highlight of Ukraine is… well, ponder the flag.

Putin the Practical

Down the halls of Russian history walk Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great, and (evidently) “The One from Lena” (Lenin). Does Putin warrant a “the” title? I suggest “Practical” fits like a glove.

I’d pose this question to Putin observers wherever they may be: Does Putin not exude practicality? It’s neither a compliment nor an insult; simply an observation.

Ukraine: Breadbasket of Europe.

Putin the Practical knows not only how the bread gets buttered, but how it gets baked. (Coincidentally, Putin’s grandfather was a cook for Lenin.) Furthermore, he understands that, as a practical matter, there’s no baking without cultivating. He’s astutely aware of agriculture’s role in Russia’s rise of recent years, so he takes a keen interest in grain production now and in a future shaped by climate change.

Putin, in other words, is a big-picture, long-term, systemic thinker in the vein of Peter Seidel’s Uncommon Sense. Having experienced the Soviet collapse, he knows all about limits to growth. While he reminisces about Soviet power, he’s no fan of the Soviet kolkhozy or the disastrous inefficiency of agriculture under the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Putin wants the breadbasket of Europe under Russian power, absorbed into the model of state capitalism he’s gravitated toward as a purely practical matter. Such absorption could go smoothly for Putin given the parallel strides of Ukrainian and Russian agriculture in recent years. If he manages to steal Ukraine, or a substantial portion of its eastern grain belt—and given the grip Russia already has over Europe with its natural gas supplies—suddenly Russia has the agro/extractive base of an unquestionable 21st century superpower.

The Currency of Currencies

“Give me control of a nation’s money supply, and I care not who makes its laws,” said Mayer Amschel Rothschild, the prototype of European banking. A century later, Lenin averred, “Grain is the currency of currencies.” On both statements Putin has probably reflected, “Of course.”

Conversely, if Putin ever encountered the notion of William Nordhaus that agriculture, because it accounted “for just 3 percent of national output,” couldn’t have “a very large effect” on the economy, he’s probably uttered, “What a идиот.” (And perhaps he thought, “No wonder those Americans, with economists like that, don’t have a clue about limits to growth.”)

Lenin and Putin would be natural adherents to the trophic theory of money. (The studious Nordhaus, despite his “just 3 percent” moment in 1991, will eventually get it as well if he doesn’t already.) Money is generated in proportion to the agricultural surplus that frees the hands for the division of labor and the exchanging of products. No agricultural surplus, no money. No real money, at least.

Which brings us as well to the contemporary crisis of inflation. Just as with Putin’s desire for Ukraine, inflation coverage by the mainstream media seems woefully lacking in agricultural insight. As we bump against limits to growth in the 21st century, food and water are the last things people will go without. Food demand is “price inelastic” in economics jargon. That means food prices will skyrocket while nominal money supplies are still… inflated. Central banks can issue all the money they want; none of it’s real (resilient against inflation) if the agricultural surplus isn’t there to match.

So what Putin wants with Ukraine goes far beyond his designs for NATO, natural gas transmission, and nationalist expansion. He wants the agricultural power of those perfectly positioned, well-drained, “black gold” soils, now and in the future. If he can steal Ukraine, he’ll have the currency of currencies (a lot more of it, that is), the best possible hedge against inflation, and adaptive capacity in the face of climate change.

In other words, Putin covets what Ukraine’s flag stands for. He wants that golden belt of grain. If he can get it, it’s blue skies ahead for Russia.

Brian Czech is the executive director of CASSE, author of Supply Shock, and co-author of the Kyiv Communiqué.

Brian Czech is the executive director of CASSE, author of Supply Shock, and co-author of the Kyiv Communiqué.

Great analysis, Brian !

Thank you for this astute analysis. I’ve had the feeling all along that Putin is a brilliant Machiavellian strategist, with a long-term perspective, and this article confirms it. Here in America, we seem to have forgotten altogether that net energy is the foundation of every economy, while money is ultimately just arithmetic. And the two primary forms of available net energy are oil and soil!

This reminds me of a table I saw years ago about the food status of the dozen or so republics of the old Soviet Union. Every one was a net food *importer*, even the huge Russian SSR, except for the Ukraine SSR (SSR = Soviet Socialist Republic).

Brian, you seem to propose only one scenario for Putin. How about the idea of NATO unencumbered trade negotiations with Putin?

Very insightful Brian! Of course no one in government or the media is reporting this because it might raise awareness of the limits to growth.

Great article, it makes a lot of sense if we also consider that Russia has essentially cut itself from the European food and agricultural market in 2014, and now has to rely mostly on its own producing lands. But I do see some flaws in your argument – I don’t think the operation that we see is aiming at invading Ukraine for any type of benefit for the Russian economy. I’d be willing to bet everything that Putin knows all too well that invading Ukraine will lead to an economic disaster for Russia – we saw a glimpse of that in 2014-2015 when the ruble depreciated, and we see how the Moscow stock exchange has been reacting to the news lately. Economic losses from this war will seriously outweigh any potential gains, if Putin is not completely insane yet, he understands that.

You’re right to mention inflation but I have a feeling that you’re tying inflation in Russia with the general inflation crisis in the world. Russia has been struggling with price inflation for a few years now. If we talk about the recent food price increase, in particular, it has more to do with seasonal supply issues. Russia grows a lot of food in the Don and Krasnodar regions in the South but lacking in modern storage and transportation infrastructure. Recently, year after year, Russia has been seeing food prices go up in the Fall and then go back down in the late Spring, and (citing Sergey Guriev on this) it indicates the lack of infrastructure, not food deficit.

If we speak in geographic (and not political) terms, there’s a more pressing issue that needs to be solved, and it’s water supply to Crimea. As it was annexed in 2014, Ukraine stopped the water supply from Dnipro through the North Crimean Canal (search for Nova Kakhovka on Google Maps if you want to see where this canal originates), and Crimea has been suffering from a lack of water for agricultural and general needs. So it’s been rumored for a couple of years now that this canal is the main target in Ukraine.

Thank you for the insightful comment. Your point about the Crimean water crisis is highly relevant, on its own but especially with how essential water is to an agricultural power base.

Your point about the “economic disaster” Putin would face in invading Ukraine is conventional wisdom and could very well hold. However, one of my points in the article is that Putin (in my opinion) is a long-term thinker. He may be calculating—as a practical matter of political economy—that the long-term economic power of a grain-belt takeover is well worth the short-term financial pain. I imagine it’s a close call either way (given the lack of a well-developed peace ethic, that is).

Russia would be well advised to stop threatening the neighbours and start cooperating. Previously a super power Russia now has the gdp ( dare i swear) smaller than that of Italy slightly larger than Spain. It can ill afford to be economically side linded in the event of an invasion. The economy has little going for it in terms of production, more similar to an oil and gas extraction economy. As the west moves away from reliance on global warming fuels Russias future looks weaker if measured in gdp and they feel threatened and insecure. Our Russian neighbours need to be more self assured, need to cooperate with the worlds team of countries to provide a safer world for themselves and others. Its with this cooperation that Russia can find a new place as a leading nation working with other to deliver sustainability and fairness.. .see the big picture… We’re all one big team on little planet earth

Yes, grain is important. That’s why Stalin organized Holodomor – a famine terror accompanied by a broader assault on Ukrainian identity – in 1932-33 in Ukraine, while exporting grains and keeping the image that everything is great in USSR (Western journalists based in Moscow were instructed not to write about it) – https://www.britannica.com/event/Holodomor. Russians have always been dreadful and slaughterous in their “practicality”.

The Holodomor Victims Memorial In Kyiv is one of the saddest places I’ve ever been. The famished little girl is clutching the grain — https://www.kyivpost.com/ukraine-politics/holodomor-statue-vandalized-in-kyiv.html — while the souls of the starved fly off the monument as cranes: https://www.shutterstock.com/image-photo/fragment-memorial-victims-holodomor-dedicated-big-2079541468 . It is profoundly touching and haunting.

Holodomor should never be forgotten. Thank you Yaryna for reminding us.

Interesting analysis. I haven’t seen this anywhere else in the media. Thanks.

It turns out that Russia is tops in wheat, but the US is the worlds largest grain exporter. Brazil believes it is headed for #1.

See:

https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/en/economia/noticia/2021-03/study-brazil-be-worlds-top-grain-exporter-five-years

The largest grain exporter in 2020 was the US, with 138 million tons. Brazil’s 122 million came second. “In the next five years, Brazil should overtake the US in exports.

Yes, Russia is a major agricultural producer in its own right, especially in the region close to Ukraine. It’s one of the biggest things Russia has going for itself.

No one should take this to mean that Putin doesn’t want more. He wants not only the grain but in particular the surplus. Agricultural surplus is the origin of money, which explains why Lenin called grain “the currency of currencies.”

In other words, taking Ukraine—or a significant portion of its grain belt—would be like robbing a giant, durable, ultimate sort of bank, bearing interest practically forever.

Thanks, Brian for filling a very notable gap in the mainstream media’s coverage of the Ukrainian/Russian border. I haven’t heard anything about whether Russia’s western border is any more insecure than its eastern or southern borders, either!?

Thanks for this piece! I’ve saved it. In college we were told to look for mineral resources, if we saw a war whose motivation eluded us. Now, enlarging the food footprint is added to the list. I understand the importance of chernozem; however, Russia could produce a lot more excellent food if it restored much of its steppe to natural grasslands and created humongous European Bison ranches. Collective ranch size, if you will. These animals don’t require the best soil to grow well and be healthy on native natural grasslands.

It isn’t necessary for Russia to control productive Ukrainian land for agriculture to increase influence in international grain markets, Putin need only to deny Ukraine’s ability to harvest and export its crops to increase Russia’s leverage for its grain exports. Russia has profited from stolen Ukrainian grain as well as getting a higher price for their grain in a stressed market.