Suing for the Steady State

by Daniel Wortel-London

Climate activists have won cases in state courts. Could steady-state cases be next? (Martin Kraft)

On August 14, Montana’s Supreme Court ruled that in light of Montanans’ constitutional right to a clean environment, the failure of state agencies to take climate change into account when considering new projects is illegal. This ruling, resulting from a lawsuit by 16 young people, is being followed up by a similar trial in Oregon—and another is pending in Hawaii. At a moment of legislative disappointment across the sustainability policy landscape, environmental victories in court are welcome signs of progress.

In this article, I’ll explore litigation as a tool for building a steady state economy. Legal challenges can strengthen and even create policies that could keep our economy operating within planetary boundaries. Current environmental litigation, however, tends to address symptoms of our ecological trespasses and not their driver: economic growth. To limit growth and the policies that promote it is the purpose of steady-state litigation. It’s time we started making a case for it.

Litigation to Advance the Steady State Economy

Litigation is an increasingly popular means of spurring ecological protection. Some 2,341 climate change cases alone have been brought to court, and more are being developed every year. Some litigants claim that pollution violates constitutional rights, such as the right to a “…clean and healthful environment…,” which is promised in Montana’s constitution.

Others argue that existing laws fail to fulfill their intended purpose by insufficiently addressing climate change. In all cases, the plaintiffs seek to require lawmakers to tighten up environmental policies.

The EPA didn’t regulate carbon emissions until a lawsuit forced it to. (Rawpixel/CC0)

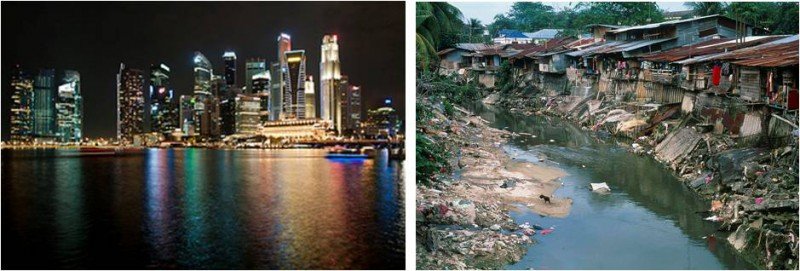

Unfortunately, environmental litigation, like environmental law more generally, tends to address the symptoms of ecological decline rather than its drivers. For example, laws and litigation are more likely to focus on regulating smokestacks than on the economic growth that drives their construction. Their ambition stops at limiting humanity’s harm to the environment.

If we think of human rights as intertwined with environmental health, however—indeed, if we think of nature as having rights—then the purpose of environmental law changes. Rather than simply trying to mitigate harm, its purpose becomes to prevent harm. That means developing laws that limit humanity’s “footprint”—particularly our throughput of material and energy—to keep economic activity within planetary boundaries. And that means limiting economic growth.

How Can Litigation Help?

The purpose of litigation for the steady state economy is to establish the illegality of any activity entailing unsustainable levels of economic activity. In practical terms, this means establishing the principle that economic growth beyond a sustainable level—growth that does not lead to overshoot—violates constitutional or statutory law. There are a few promising avenues for doing this.

One is to show how policies promoting economic growth can violate state or federal constitutional rights. Many states require all legislation to serve the “general welfare.” Other states require that policies such as eminent domain—the taking of private property by the public sector—“provide for the public health, safety, and morals.” And Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution states that the Congress shall “… provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States.”

A growing number of lawyers argue that global warming violates these rights.

Does it follow that the economic growth that, to an inarguable extent, causes climate change can also be deemed unconstitutional? Can economic growth, for example, endanger the “general welfare”?

Is economic growth unconstitutional if it undermines the “general welfare”? (Cowtools)

We know it can. We know that economic growth can generate stress and undermine communities, leading to increased depression and suicide. We know that economic growth can eat away at the natural capital that is the foundation of our prosperity. And we know how the damage economic growth inflicts on our environment can erode our health, safety, and “general welfare.” All these examples of what Herman Daly called “uneconomic growth” are therefore threats to both our lives and our legal rights.

And some state courts have begun to recognize that economic growth can threaten constitutional privileges. For example, public outcry after the Supreme Court’s Kelo Decision of 2005 encouraged state courts in Ohio and Michigan to strike down pro-growth eminent domain decisions, on the grounds that economic growth didn’t sufficiently constitute a “public use” or benefit the “public welfare” as defined in their state’s constitution. And if eminent domain on behalf of economic growth can be ruled unconstitutional, perhaps other policies on behalf of growth can as well.

In fact, cases can be made that economic growth violates many federal laws. The Clean Water Act, Clean Air Act, Endangered Species Act—these and other laws commit the government to protecting various dimensions of the environment. And lawyers increasingly argue that policies that contribute to climate change violate these acts. The National Environmental Policy Act alone has been the basis of 396 lawsuits by litigants arguing that climate change wasn’t sufficiently addressed in environmental impact statements and assessments.

If these laws are violated by policies that directly accelerate climate change, such as opening federal land to oil drilling, they are also violated by the pro-growth policies that indirectly accelerate climate change.

On these grounds, environmental lawyers could target every pro-growth policy and every decision that increases throughput as a statutory violation. Free-trade agreements would seem to violate the Clean Water Act. Highway construction undermines the Clean Air Act. Monetary policies by the Federal Reserve can violate the Endangered Species Act. The point is that almost every pro-growth policy, no matter how subtle, is potentially a target of litigation.

Making a Start

Most environmental litigation, of course, has shied away from explicitly tackling “economic growth” as an ecological threat. Some plaintiffs have come close: Litigants in one major Dutch case stated that “as a result of a growing global population and increasing economic activity, ecosystems (and biodiversity) are under pressure all over the world due to, inter alia, overconsumption, deforestation, pollution and other excessive use of natural resources everywhere.”

Generally, however, climate litigants employ “win-win” rhetoric: Whereas oil companies claim regulation will harm economic growth, environmental lawyers claim the two can go hand-in-hand. This cheery posture may be politically useful, but it’s also fundamentally flawed.

From the streets to the courts, an expanded mission. (US Government, public domain)

Now we need to apply the principles of ecological economics to real cases pursued by real lawyers. Doing so can help reveal new pathways for introducing steady-state principles into policy.

Of course, taking the litigative path will not be easy. For example, in 2007, Massachusetts and several other states successfully , which ruled that the EPA was bound to regulate carbon dioxide emissions. But that case was largely overruled by a subsequent 2022 Supreme Court decision, whereby the Court ruled that the autonomy of agencies like the EPA was strictly limited by Congress.

It is possible that steady-state litigation will be more successful at the state than at the federal level. But we won’t know until we try. Thankfully, a growing number of environmental lawyers are eager to take this step.

This is not to say that steady staters should prioritize litigation over other tools for advancing the steady state economy. A Steady State Economy Act, arrived at democratically and passed by Congress, remains our ultimate goal.

But remember: In the USA, everything that can be legislated can be litigated. And that fact just might save the planet.

Daniel Wortel-London is CASSE’s Policy Specialist.

The Montana legal case, first paragraph of the above article, seems to have been triggered by grass roots activists. I would guess that litigation strategy would need to be in sync with grass roots activism. The Civil Rights Act, for example, would not have been achieved without long struggles from the ground. The ideal for a steady state litigation strategy could surface if people on the ground who trigger lawsuits organically espouse a steady state message. Sadly, it has sometimes turned out in reverse, with environmental activists being put in jail, and legal specialists forced to act on the defensive.