The Environmental Consequences of Putin’s War

by Connor Moynihan

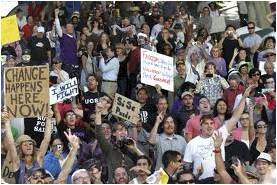

Perhaps the famous Vietnam-era poster should be amended: “Growthmanship is not healthy for children and other living things.” (CC BY-NC 2.0, qbac07)

Steady-state advocates know that peace is required for a stable and prosperous world. Herman Daly said, “It is hard to imagine a steady state economy without peace; it is hard to imagine peace in a full world without a steady state economy.” Brian Czech emphasized succinctly, “Peace is a steady state economy.” And peace campaigners have long connected their goals to the environment. For example, U.S. anti-war activists rallied behind the cry, “War is not healthy for children and other living things,” in response to the use of napalm and Agent Orange in Vietnam.

When Putin and Russia invaded Ukraine, over 1,000 multidisciplinary experts signed an open letter concerning the environmental hazards. They called attention to the dangers of fighting near nuclear plants and dams, which have since been assaulted. They also highlighted threats to the food supply and the economic weaponization of oil and gas reserves, as well as the potential impacts of the war on biodiversity:

Fighting in the Black Sea Biosphere Reserve—the largest protected area in Ukraine and a listed Ramsar wetland–has generated fires that can be seen from space…While we may not know the full environmental impacts of this war for some time, history shows that the effects will be far-reaching and long-lasting. Thus, there is a need for rapid environmental assessment, long-term monitoring, and accountability.

The environmental impacts of war are sometimes covered in mainstream outlets, but are seldom linked to the goal of economic growth. By examining the environmental consequences of this invasion, the role of growthism becomes clear.

The Biodiversity Impact of War

“Warfare ecologists” have surveyed 146 conflicts from 1950 to 2000 and found that 90 percent of them took place in a country with a biodiversity hotspot, and 81 percent had fighting in the hotspots themselves. Ukraine doesn’t have or comprise a biodiversity hotspot per se, but it’s disproportionately important in the European biodiversity context. Ukraine comprises only six percent of Europe’s total landmass, yet contains 35 percent of the continent’s biodiversity, including 81 endemic species (that is, species found nowhere else).

Ukrainian endemic species such as the sandy blind mole-rat are lesser-known casualties of Putin’s war. (CC BY-SA 4.0, Максим Яковлєв)

Military operations have numerous effects on biodiversity. They tear up ecosystems and make them susceptible to invasive species, which in turn are frequently transported via military vehicle (on the ground, in the air, or at sea). Additionally, military operations emit noise pollution that’s harmful to animals, disrupting their behavioral and reproductive patterns.

Soldiers taking shelter in forests poach at higher rates, air-to-ground assaults defoliate forests, and sonar causes hemorrhaging in cetaceans. Sub-marine detonations can cause barometric trauma, or “overpressure,” in marine species, causing tissue destruction or instant death. Some of these risks have already been evident in Ukraine. Illegal hunting is a listed concern in Ukraine’s fifth report to the Convention on Biological Diversity, as 16 percent of their land is forest. There has also been a rise in cetacean strandings in the Black Sea that scientists suspect may be caused by Russian naval activity.

Beyond Biodiversity

Putin’s invasion was initially launched on multiple fronts in Ukraine, with most of the warfare concentrated in the south. Zaporizhzhia, an area of intense fighting, is home to two of the five iron mines in Ukraine. Before the war, Ukraine was the third largest exporter of pig iron with about half of their exports ending up in the USA. Ukraine has the world’s seventh largest coal reserves, with much of the coal found in the Donbas region. Mining activities impact the environment long after the projects are abandoned; adding explosive destruction to the mix only furthers this damage.

As Russia targets Ukraine’s nuclear plants, memories of the Chernobyl disaster turn ominous. (CC BY-SA 2.0, IAEA Imagebank)

In 2020, Ukraine increased steel production to nearly 2 million tons. Many of the country’s steelworks plants, around a third of which are located near Mariupol, fell to Russian forces in May. Neon gas, a byproduct of steel manufacture, is another important product of Ukraine, with major refiners located in Odesa. Since turning their attention to the east, Russia has continued harassing the port city. In the absence of bombs, steelworks emit heat and fine particulates such as lime, oil, dust, and iron (bi)carbonates. How much more has been released into the air and water due to warfare?

Nuclear plants pose an entirely different level of risk. Half of Ukraine’s electricity is generated by 15 nuclear reactors. Nuclear radiation is associated with devastating health effects, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, and acute radiation syndrome. In March, a fire broke out at Zaporizhzhia, home to Europe’s largest nuclear plant, and Russia took control of the plant. Luckily, five of the six reactors had already been shut down when the fire broke out and the radiation levels have since been reported as normal. The plant, however, continues to operate with Ukrainian staff under Russian control. Some suggest Russia is using Zaporizhzhia as a “nuclear shield,” as Ukrainians are loathe to fight fire with fire near nuclear reactors.

Early on fighting broke out near Chernobyl as well, as Ukrainian soldiers fought to prevent a repeat of the 1986 disaster. Despite being one of the most toxic places on Earth, Russian forces bulldozed through the nuclear site, exposing themselves and others to possibly dangerous amounts of radiation lingering beneath the surface. Russian troops ignored the restricted airspace around the site along with other safety precautions in place to lower the risks of radiation exposure to Ukraine, nearby Belarus, and beyond.

What’s more, a losing Putin could decide to use nuclear weapons. Russian military doctrine permits the use of nuclear weapons to defend Russian land. Therefore, if Ukraine counterattacks to reclaim lost areas such as Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Donetsk, or Luhansk, Putin may justify nuclear warfare to protect the newly annexed territories.

War and Growth

Putin’s growthmanship has inspired an expansionist war for resources. Russia’s own territory is 49 percent forest, making it one of the most important carbon sinks in the world. About ten percent of its forest cover has been lost since 2000 due to fires, many of which are in boreal and Arctic regions, contributing to the melting of permafrost, turning some areas from carbon sinks into carbon sources. Sakha and Krasnoyarsk, the economies of which are heavily extractive, are losing forest the fastest. In Sakha, the main industries are mining and timber, while Krasnoyarsk is home to intensive aluminum production and other heavy industries.

Carbon sinks cut for economic growth. (CC BY 3.0, Druschba 4)

Russia’s historical emphasis on manufacturing has come at great expense to the environment, with one river surpassing mercury standards by 2,000 percent. Soviet-era dumping is largely responsible for today’s widespread water pollution, the country’s most pressing environmental issue. Forty percent of surface water and 17 percent of spring water in Russia is impotable due to excessive amounts of chemicals, sewage, and toxic waste.

Russia exports fourteen percent of the world’s crude oil and eight percent of its natural gas. Its largest energy source after fossil fuels is nuclear. Although agriculture makes up only six percent of Russia’s GDP, agroindustry is of paramount importance to Russian leadership. Russia’s parliament and presidents have pushed for agricultural self-sufficiency since 2000, and the country has moved from being a net importer of grain in the 1990s to a key exporter in merely a decade.

In 2010, the agriculture industry set extra-high production targets, and recently increased them again in 2020. In 2014, Russia responded to U.S.-led sanctions by banning certain agricultural imports, and these policies have reduced competition in Russian agriculture and exacerbated inequality in an already unequal society. Furthermore, the oligarchic industry has kept food prices high, despite the ramped-up production.

What emerges is a clear, big picture familiar to steady staters. The economic requirements and ecological costs of growthmanship don’t stop at national borders. Instead, they spill over violently in the quest to maintain the upward trajectory of the national account. Perhaps the old anti-war slogan should be revised to reflect the reality that “growthmanship is not healthy for children and other living things.”

Connor Moynihan is an environmental studies intern at CASSE.

Connor Moynihan is an environmental studies intern at CASSE.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

(No profanity, lewdness, or libel.)