Contrasting Climate Policies in the House and Senate

By Brian Snyder

On March 10, Senate Majority Whip Dick Durbin introduced America’s Clean Future Fund Act, a fairly ambitious plan to combat climate change. While skeptics will be able to identify plenty of weaknesses in the bill and might argue that it remains enmeshed in a growth-economy worldview, the potential for progress warrants our appreciation. Meanwhile in the House, the Energy and Commerce Committee introduced the Climate Leadership and Environmental Action for our Nation’s (CLEAN) Future Act, which is even more ambitious, although it still seeks to address climate change while growing the economy. So, what’s in the legislation? Let’s start with the Senate.

America’s Clean Future Fund Act

A Carbon Fee

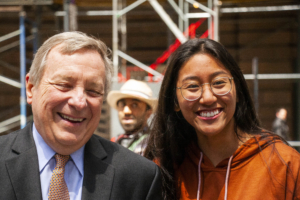

Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL) at the Youth Climate Strike, Chicago, 2019. (Image: CC BY-SA 2.0, Credit: Charles Edward Miller)

Under America’s Clean Future Fund Act, beginning in 2023 a carbon “fee” of $25 per tonne will be applied to upstream sources. The fee is indexed to ratchet automatically to the consumer price index. This would amount to the first carbon tax in the USA and would very likely put the final nail in the coffin of the coal industry. It would also slow natural gas power plant construction which, given the most recent estimates of methane leakage, is very important. What’s not to like?

While $25 per tonne may seem drawn from thin air, so too are most estimates of carbon prices. One way of thinking about the “right” price for carbon emissions is to ask what the price needs to be to incentivize cleaner production. That is, if a fee of $25 per tonne suffices to phase fossil fuels out of the economy, then perhaps $25 per tonne is a good number.

Finally, people might not like that the fee only applies to large, “upstream” emitters and not cars and trucks. This might be a political calculation and it might make implementation easier, but I think it’s a mistake. Transportation is rapidly electrifying, but if we tax emissions only at the powerplant and not at the tailpipe, we will incentivize internal combustion vehicles over electric vehicles (EVs).

Climate Change Finance Corporation

On the surface, this sounds like a bad idea. This new agency will be tasked with providing financial support and investment in clean energy projects, climate resilience, and R&D. This is clearly intended to support economic growth, and so a healthy dose of skepticism is warranted. However, the bill also claims that at least 40 percent of grants will go to environmental justice communities.

The emphasis on EJ communities transforms this proposal from just another green-growth idea to a (potentially) targeted approach for creating jobs and security where they are most needed. This leaves the agency open to potentially serving steady-state purposes in the future.

Transition Assistance For Impacted Communities

This is sort of the non-profit and community-centered version of the Climate Change Finance Corporation, and the most important part of the proposal. Durbin proposes to provide grants to states, local governments, non-profits and community organizations to alleviate the social and economic injustice of decarbonization. This is critical because without local support, any decarbonization policy will fall apart.

As one of my students said the other day, we cannot simply say to the people employed in coal country, “Sorry mate, you’re out of luck. Maybe next time don’t get a job in an industry that destroys the planet.” For far too long, the environmental movement has ignored the concerns of current people in favor of non-human life and future generations. We all too often forget that we cannot accomplish any of the things we want for future generations without the support of current generations. Durbin’s bill addresses this, to his credit.

Sequestering carbon in soils is one way to keep it out of the atmosphere. (Image: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, Credit: Georgina Smith)

Along with forestry, soil carbon is one of the easiest and cheapest means for removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Methods for storing carbon in soil can be as simple as lessening tillage or adding biochar. Durbin’s bill provides financing to help farmers participate in global carbon markets. This is a fine idea, but the proposal could be far more ambitious. The bill helps farmers participate in the market, but it doesn’t set up a tax credit. 45Q, that section of the tax code pertaining to carbon capture and storage, could be amended to provide incentives for carbon farming.

Rebates to Individuals and Refunds for Carbon Capture

In order to make the bill more palatable to tax-averse Americans, we get the carbon fees back in the form of a rebate. The good news is that this rebate goes to low income-families who truly may need it—the bad news is that it will also go to middle-income families who likely don’t. There are also incentives for carbon capture, including carbon dioxide removal systems. This could be a critically important policy if it were well-funded. Unfortunately, Durbin’s bill only provides modest support equal to the value of the carbon fee.

Climate Leadership and Environmental Action for our Nation’s (CLEAN) Future Act

Clean Energy Standards

The House bill proposes what is essentially a renewable portfolio standard, but it is extremely ambitious and requires 80 percent renewable generation by 2030 and 100 percent by 2035. I don’t think this is technically feasible. In order to build that much new generation, we would need a supply chain to fabricate photovoltaic arrays and wind turbines. We would need to be able to deploy at scale technologies that are currently only deployed as prototypes like high altitude wind power, offshore wind power (yes, I know other nations use offshore wind at scale), and marine hydrokinetic energy. And we would need so many batteries. I would love to be proven wrong but reforming the energy industry is not like sending a man to the moon or developing a vaccine—it is far more difficult.

On the plus side, the bill also requires accounting for upstream gas leakage. On the downside, knowing the actual gas leakage rates would make that task more reliable.

Electricity Transmission

The House bill proposes a bunch of much needed electricity transmission, including improving east-west interconnections which will aide in the movement of renewable energy. This is hugely important and should be non-partisan because who doesn’t like improved grid reliability and efficiency? Of course, it is partisan because it also helps wind and solar producers out-compete coal leading the Trump administration to kill even the study of the issue. (In my opinion, if the Trump administration hated it, it is probably a good idea.)

EV Charging

The Bill includes the reauthorization of a $2 billion annual program which funds projects that electrify transportation. The bill also requires the federal government to increase the proportion of electrical vehicles (EVs) in its fleet.

Environmental Justice

Like Durbin’s bill, the House seeks to make 40 percent of the total funding appropriated through the act available to EJ communities. There is also a special emphasis on EV infrastructure in underserved communities, and new EJ training for the federal workforce. As in Durbin’s bill, the impetus seems to be from the Biden administration, but this sort of 40 percent allocation to EJ communities should be on all environmental legislation.

Clean Energy and Sustainability Accelerator

Electric vehicles: great for climate, given a the right grid. (Image: CC BY-SA 2.0, Credit: Bill Abbot)

Because no bill is complete without public monies flowing to private firms, the House wants to spend $100 billion on an accelerator program which would fund loans and grants to the public and private sectors to finance clean energy development.

What Would Make them Better?

Both bills have holes that the other can fill. Durbin’s carbon fee is a better idea for decarbonizing the power sector than the House’s clean energy standard. But the House’s investment in electricity transmission is critical and missing from Durbin’s plan.

Of course, missing from both is an acknowledgement of the fact that all of this will be made much simpler if national energy demand decreases or at least stays constant. For the last decade, we have used about four trillion kilowatt hours of electricity per year. If we electrify our transportation sector, electricity consumption will increase. Further, as we add long-distance transmission, battery charging, and non-renewable curtailment, the efficiency of electricity generation will decrease and so generation will need to increase further.

One way to help make the goal of 100 percent clean energy by 2035 (House bill) more achievable is to take steps to limit the growth in demand. This could be through simple investments in rail and mass transport and increased funding for efficiency improvements (which gets a little attention in the House bill), or it could be through big changes that temper economic growth like those proposed by CASSE.

At a more basic level, neither bill seems to find it ironic that they intend to combat climate change by stimulating the economy. The House bill, and to a lesser extent Durbin’s bill, pours money into a variety of programs to accelerate decarbonization. Presumably this money will come mostly from new debt, although to its credit, Durbin’s bill is funded largely from his carbon fee. Yet to the extent that we use debt to fund decarbonization, we may stimulate the economy we seek to decarbonize. This is a specific case of the “trophic conundrum” identified by Brian Czech: You can’t buy your way out of environmental problems, because generating money causes environmental problems! Climate policy needs to be debt neutral, or better yet, debt negative. If you know that financial crisis may be on the horizon, you would be wise to try to save for it; climate change threatens to create several such crises.

Of course, no bill is perfect. But the question for those of us concerned with the effects of economic growth is: Should we let the perfect be the enemy of the good? Finally, after 30 years of essentially no progress on climate in the U.S., we have two good bills with plausible odds for success. Neither bill will create a steady state economy; indeed, their intention—“green” growth—is just the opposite. As a result, over the long term, both bills might help to create new environmental problems. But when your ship is sinking you aren’t picky about the lifeboat that comes along.

We are just insane as we continue to perpetuate the false reality of green growth or otherwise. The real underlying issue is growth modified by any adjective is physically absurd. Growth is thus the high crime that will ultimately lead us to extinction.

However, lawyers and politicians do not have the wisdom to comprehend that numbers speak louder than words…we will never defeat them and their resultant infinity.

Fridays For Future

T A McNeil