Growth Battles in Chittenden County

by Dave Rollo

The Green Mountains of Vermont. (JJ Sky’s the Limit)

Vermont takes its name from the French Monts Verts, or Green Mountains, the state’s rolling hills that host maple, birch, and beech forests in the south and spruce and fir in the north. Quaint towns and farms, many retaining their historic structures, are nestled in the mountain valleys. Lakes, streams, and wetlands are plentiful. And farms are everywhere: Vermont consistently ranks as one of the top states in the nation for local food production.

The verdant beauty of the Green Mountain State is striking, but preserving its beauty is a struggle as the state’s fields and forests attract green of a different kind. The state’s revered rural landscapes represent potentially lucrative investments for developers.

Developers have sought to expand urban development into surrounding green areas since the end of World War II. This is particularly evident in Chittenden County, the home of Burlington, Vermont’s largest city. More than a quarter of Vermonters live there, and it remains on the front line of the struggle against sprawl. Recent battles there highlight the tensions between providing housing and protecting the environment. They also demonstrate that well-organized groups of citizens can make inroads against powerful pro-growth interests.

Burlington’s Growing Pains

In the latter half of the 20th century, Chittenden County lost farmland at an alarming rate; farmland’s share of total area fell from 73 percent to just 24 percent between 1950 and 1992. Commensurate with this loss was a doubling of population. And since 1945, the number of residents has more than tripled.

In the late 1960s, politicians and the public began to clamor for action to prevent further loss of land to sprawl. The legislature responded in 1970 with Act 250, a landmark land-use statute. Years later, the Republican governor who signed the legislation recognized the Act as the most significant of his administration.

Act 250 marked a sea change in land use. It required that a project, after passing review at the local level, meet ten criteria to earn further review by the state’s Natural Resources Board. Then it is reviewed by one of nine regional Environmental Commissions. Environmental Commission review has been particularly successful in regulating developments of ten or more housing units or building lots.

Analysts credit Act 250 with protecting Vermont’s agrarian spaces, wetlands, and forests. The development process mandated by the Act encourages the participation of neighbors in targeted areas, bringing the perspectives of various stakeholders before the commissions. Although developers find the requirements onerous and time consuming, most permits are granted—none were rejected in 2022, and only one was rejected in 2021.

Will the scarlet tanager continue to have a home in Vermont? (Jen Goellnitz)

Still, developers complain of a chilling effect of the Act, as the review can be lengthy and costly. And housing advocates, concerned about housing scarcity and rising home prices, have joined developers in critiquing the Act.

Legislators are now debating reform of Act 250, which the current Governor favors. Changes are likely soon. Some proposed changes are quite benign, such as exempting farm restaurants or farm stands from the density provisions of the law. But loosening standards and lowering barriers threatens to generate the very sprawl that the law was enacted to prevent. Resident groups such as Better (Not Bigger) Vermont eye the growing coalition of developers and housing advocates with concern.

Meanwhile, the legislature adopted the Home Act in June 2023, which critics fear could encourage sprawl. The intent of the Home Act is purportedly to elevate density in village centers of rural communities to increase housing stock. To this end, the Act permits “plexing,” the subdividing of existing single-family homes, usually to create rental units.

While creating density through plexing could be beneficial in town cores, the Act’s simultaneous elimination of single-family zoning statewide reduces opportunities for home ownership, a key strategy for building wealth. In contrast, duplexes convert housing stock to rentals where equity building isn’t possible.

Many advocates of a supply-side approach to the housing crunch fail to consider that the problem is not just a shortage of structures, but how they are used. Short-term rentals (Airbnb) and the purchase of second homes effectively take homes off the sale and rental markets. The effect is to reduce housing availability in Vermont, just as it does elsewhere in the country.

Infrastructure and Growth Pressures

As the state legislature begins to ease development review and encourage greater density through upzoning (allowing greater height, density, or both), local governments are responding by relaxing local land-use codes. Planning commissions typically develop eight-year plans and create zoning regulations that are forwarded to selectboards, the legislative bodies that govern towns in Vermont. The revision of zoning plans provides an opening for growth advocates to expand development in rural towns—especially the bedroom communities of large cities such as Burlington.

Summer 2023 algal bloom in Lake Champlain. (southherovoters.org)

Growth in these communities takes infrastructure, such as roads and waterworks, which benefits developers. Expanding sewer treatment, for example, is a prerequisite of housing and commercial development. At least, it should be a prerequisite. Unfortunately, a common practice of growth advocates is to pressure communities to develop more housing even though existing infrastructure is inadequate to accommodate it.

Many communities impacted by growth and sprawl commonly complain about a lack of concurrency of infrastructure and services—ensuring that infrastructure is possible and affordable before a new area is developed. But concurrency is rarely prioritized, leading to stress on existing infrastructure that is costly in both environmental and economic terms.

In Vermont, the case of combined sewer systems, in which sewage and stormwater flow through the same pipes, demonstrates the lack of infrastructure capacity. Combined sewer-stormwater infrastructure renders water treatment vulnerable to flooding during heavy rains. This can bring about sewage overflows into waterways, such as the White River, a tributary of the Connecticut River, the largest river in New England. Sewage overflows also contaminate Lake Champlain.

Heavy summer rains in July 2023 caused an antiquated sewer pipe to rupture, spilling 10 percent of Burlington’s wastewater into the Winooski River, which feeds into Lake Champlain, causing extensive contamination of the lake. Combined sewer-stormwater overflow also contributes to poisonous bacterial blooms, which diminish fishing and swimming opportunities and threaten the health of pets and wildlife.

During the COVID pandemic, federal funding from the American Rescue Plan (ARPA) was ostensibly made available for upgrading antiquated sewage systems such as combined sewage-stormwater systems and septic fields. However, in Vermont this funding was often used to expand sewage treatment plants in rural areas, stimulating growth there. As a result, combined sewage-stormwater systems still plague the state.

Westford Pushes Back Against Growth

Westford, Vermont, a town less than 10 miles from greater Burlington, illustrates how citizens can stand against development interests to protect small-town rural character. In 2023, the state proposed use of ARPA funds for construction of a wastewater treatment plant that would permit a 60 percent increase in Westford residences. Ninety percent of the construction cost of the $4-million plant was to be financed by the state, but Westford residents needed to approve a bond to cover $400,000 of the cost.

Westford, Vermont town center. (Bernhard Wunder)

Knowing that the plant’s extra capacity would be utilized by development interests, residents joined forces to educate the town and vote down the referendum that was required for the bond passage.

Residents found themselves pitted against the town planning commission, and the local media was unsympathetic to their objections. They were even removed from a statewide listserv used to provide information on the project, according to Bob Fireovid, a farmer and activist in the greater Burlington area.

Despite these obstacles, the group created a political action committee and a website with information including videos describing the proposal. They also peppered the community with signs urging a “No” vote on the referendum. To the surprise of the growth boosters, the referendum was defeated in November, 2023 in a 532-to-488 vote. Furthermore, the Westford Selectboard went further, declaring that the vote represented not just a rejection of the bond, but a referendum on the wastewater project. The project is now suspended

Tale of Two Heroes

Other rural communities threatened by Burlington sprawl are the towns of North and South Hero, located on Grand Isle in Lake Champlain. South Hero is just 12 miles from Burlington, while North Hero, on the northern end of the island, is more distant. Towns in Vermont make changes to their town plans every eight years, and both Hero draft plans were opened to public review in 2022. A referendum in South Hero and a vote by North Hero’s Selectboard were then to follow. That’s when residents got busy.

Many residents of both towns were alarmed at the extent of the proposals, which increased density and altered zoning over large areas extending from their town centers. The plans, they argued, weren’t created in the interests of residents at large, but to serve commuters to Burlington, South Burlington, and Essex Junction.

Residents of South Hero developed a website to post planning documents, alert neighbors to upcoming meetings, and describe the hazards of a plan that would have expanded development into their rural community.

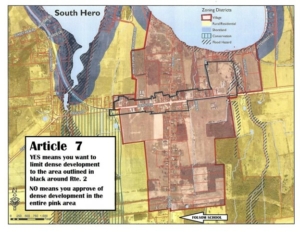

On the South Hero ballot were two alternative proposals: one to limit the extent of growth and the other to expand the dense development many-fold. The proposal to limit sprawl failed by about 50 votes of the 650 cast.

The referendum question for South Hero. (southherovoters.org)

In contrast, residents of North Hero opposed to comprehensive density increases were able to restrict multi-family housing primarily to a limited zone near the town center. The North Hero Selectboard will permit denser housing in rural neighborhoods only by conditional use, which requires a board hearing with public input.

Moreover, recommendations by the town’s planning commission to decrease rural minimum lot size from three to two acres was rejected by the North Hero Selectboard. The commission had recommended a more expansive zoning allowance for multi-unit development, but residents convinced the North Hero Selectboard to adopt the more limited area, with density increases in the larger jurisdiction left to a matter of conditional use.

The divergent outcomes in South and North Hero hold important lessons for advocates of restricted growth. In South Hero, advocates lost, but narrowly, demonstrating the near-effectiveness of their organizing and communications efforts. Their network and template of action can be deployed in the next attempt to update their town plan.

In North Hero, a committed group of residents were successful in resisting the most ambitious objective of the growth boosters, which would have adversely affected their quality of life and negatively impacted their island’s environment.

Together, the two cases demonstrate that citizen action can move the needle in opposing growth. The Heros have constructed constituencies for eventual success, if not initial victory.

A Recurring Theme

Chittenden County’s growth struggles pitting the preservation of scenic beauty, rural character and agricultural base against housing development are a recurring theme in counties across the country. Preservationists have traditionally stood up to development interests, but today the latter are joined by “affordable housing” advocates who contend that the demand for housing should be met with more supply—and therefore, that communities need to grow. This is the argument and impetus of easing the current standards of Act 250, and the frame of mind of planners and elected officials who modify zoning.

This clash of interests must ultimately be resolved by means other than accommodating ever more housing if Vermont is to retain its rural character, protect its production of food, and conserve wildlife habitats. While density can play a part in accommodating housing, it should be localized so as not to undermine decades-long efforts to limit land development impacts.

Equal attention should be placed on limiting short-term rentals and the trend of investors buying up housing stock. Efforts to limit these trends probably require federal action.

In the meantime, residents of Vermont have had some success in restraining urban encroachment, serving as examples of steady-state citizenship at the local level.

Dave Rollo is a Policy Specialist and Team Leader of the Keep Our Counties Great program at CASSE.

Thanks for letting the world know about our small state’s development struggles. We have become an escape destination; escape from climate change induced droughts, wildfires, etc. This has encouraged the real estate developers to set their sights on Vermont. Around a million dollars were gathered from mostly local businesses and the VT Chamber of Commerce to create an “educational ” non-profit (vtfuturesproject.org) to make the case for the need of 150,000 more people (on top of our present 650,000+) and 33,000 more housing units in the next 12 years. The main need expressed was for more younger people needed to work in the trades, and more children to refill the emptying schools. A concern about food resilience in a future of energy descent was to be solved with “new technology and increased efficiency”( sort of a standard answer from economists).

Until politicians and local, state and national governments acknowledge that the environment is our economy we will continue to experience the push for more building construction. Too, recognition is needed that a GDP economy is a destructive one and growth at all costs that sacrifices the health and welfare of our people and environmental quality is not an acceptable one. A steady state economy is needed that will incorporate limits to population growth and housing numbers. One that emphasizes the quality of living and reduction of extraction and consumption of natural resources.

required for sustainability.

No mention of population growth, the driver of all this sprawl. See NumbersUSA’s recent publication “From Sea to Sprawling Sea: Quantifying the Loss of Open Space in America,” https://sprawlusa.com

We aren’t going to “Keep Our Counties” great if we keep crowding out other species with ever more people.

My little borough of Swarthmore, a college town in southeastern Pennsylvania, is going through just such a process. An Affordability Task Force was so popular it had to turn volunteers away. We now have a tentative proposal for our Town Center to allow taller buildings, and an RFP is in progress to recruit a consultant to draft a new Comprehensive Plan. I went to a committee meeting and made a public comment pleading for the Comp Plan to incorporate resilience, without using that word, and two of the three committee members clearly had no idea what I was talking about. With the coming Troubles now baked in from 200+ years of unsustainable industrialization, we need to make sure any land we have available goes into growing food. Yet a survey showed that the priority on most residents’ minds is developing a “vibrant” town center.

There seems to be no such thing as a reality check.

People who act sanely about their household budget are utterly insane about the planetary budget.

But what are you going to do with the products of growing population? People coming of age and needing housing didn’t give birth to themselves, although they might have immigrated here from elsewhere. Is there any way to be kind to the humans who exist through no fault of their own, yet discourage the production of more humans? Yeah, I know the old story about educating women and girls. Actually, it’s more like empowering women and girls. But with a cultural mandate to desire children, even that is not enough.