It’s Time to Ban Earth-Damaging Ads

by Daniel Wortel-London

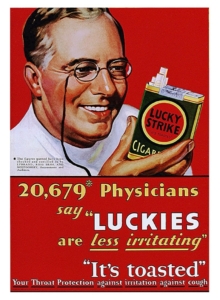

Cigarette ads are restricted in many countries. What about ads for other unhealthy products? (Clotho 98, Flickr)

Advertising works. A recent study by the Advertising Association finds that every dollar of ad spending drives up sales by $21. Ads get us to recognize brands and hum jingles even if we are annoyed by pop-ups. They are particularly effective in driving the kind of unsustainable consumption that is destroying our planet.

This begs a question: Should advertising be limited for the sake of the environment? Is there political demand for such restriction? Is it even legally possible? The answer depends on which ads are banned, in what places, and at what times. But there’s a growing movement to ban advertisements for the most egregiously wasteful products and services, from fossil fuels to air travel.

For example, ads for fossil fuels have been banned in France and in 33 cities around the world. Associations of physicians, students, and climate activists have taken part in the campaigns like the fossil fuel ban. These efforts merit being replicated and expanded to spread a broader message: There’s a limit to how much consumption our planet can tolerate.

Promoting Pollution

What are the societal costs of advertising? We can start with climate change, whose roots in fossil fuel use are well known. Fossil fuels account for more than 75 percent of all global greenhouses gases and 90 percent of all carbon dioxide emissions. Then there are the health problems caused by these gases: In the United States alone, 350,000 premature deaths are attributable to air pollution.

It gets worse. Ads not only drive planet-wasting consumption, they are designed to convince us that this waste isn’t happening. Ads for fossil fuel companies routinely boast of their commitments to “clean energy” even as they pour money into the most polluting energy technologies. A recent study found that 60 percent of the advertisements produced by the five biggest oil companies contain “green claims,” even though they spend only about 10 percent of their capital budgets each year on low-carbon investments. A 2022 investigation by the House Oversight and Reform Committee concluded that “fossil fuel companies have been misleading the public about their purported commitment to reduce emissions.”

What you won’t find in a typical fossil-fuel ad. (Arby Reid, Creative Commons 4.0)

There’s a name for this kind of deceit: greenwashing.

To a certain extent, public bodies have begun to crack down on greenwashing in advertisements. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission has produced a new “green guide” that seeks to prevent companies from making deceptive environmental claims. The City of New York has filed a lawsuit against major oil companies for violating the city’s consumer protection law through “false advertising.” Actions like these are commendable.

But it isn’t enough to hide false claims. Promoting consumption of any kind, no matter how “green,” produces environmental impacts. To stay within the planet’s environmental boundaries we need to limit consumption. This means reducing advertisements that promote particularly wasteful products such as fossil fuels, and those directed toward people who consume the most, namely, the super-rich.

A Movement Grows

The good news is that there is a growing movement to ban such advertisements. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change identifies advertising regulation as a policy measure that can reduce carbon emissions significantly. A panel of 12 prominent scientists has advised the Dutch Minister of Climate and Energy Policy that “a ban on fossil ads is essential for the sustainable transition.”

And citizens are responding. Health professionals in Canada are launching a campaign to ban fossil fuel ads in their country. There are similar national campaigns in Australia, as well as local campaigns in Cape Town, Berlin, and Geneva. Such campaigns have been supported by groups including the World Wildlife Fund, Greenpeace, the Green Student Movement, 350.org, Extinction Rebellion NL, and the Global Climate and Health Alliance.

There’s a growing movement to ban fossil-fuel advertisements around the world. (Matt Brown, Wikimedia)

They are getting results. In 2022 France passed a climate bill that banned advertising of all fossil fuels. Amsterdam, Sydney, and Liverpool have adopted similar bans in their jurisdictions. Thirty-three smaller cities in Australia, England, and the Netherlands have passed similar legislation.

That’s just the beginning of ad bans on environmentally problematic products. At least two cities in the Netherlands have banned industrially farmed meat and dairy products—industries with enormous environmental impacts—from public billboards. Other movements are pushing to extend the range of bans to cover products related to aviation, cruise ships, or automobiles. France now bans advertisements for gasoline-powered cars, and smaller cities have passed similar broadly impactful bans.

The USA Needs to Catch Up

Meanwhile, there isn’t a strong movement in the USA to ban wasteful advertising. We’ve seen ads banned on other grounds, of course. Cigarettes have been banned since the early 1970s, prompted by evidence linking smoking to low birth rates. Many states ban advertising that depicts minors gambling, and drives to further ban online advertisements for sportsbooks are in place at the federal and state level. But there isn’t a similarly strong drive to ban products because of their environmental impacts.

Many U.S. states have banned some advertising for gambling: Will they do the same for oil products? (Andie712b, Wikimedia)

Then there’s the question of free speech. Since 1980, government bodies have been required to meet four criteria to regulate advertisements. They have to show how an advertising message is misleading; identify a legitimate public interest in curtailing the message; show that their regulation would advance that interest; and most importantly, apply a “least restrictive means” test showing that they are suppressing only as much speech as is proportional to their goal.

Prospects for Widening the Bans

Can a ban on fossil fuel advertisements or other ads that promote environmentally harmful products or activities pass these kinds of tests? They would very likely pass the first three criteria; the fourth might depend on the specific ban proposed. But merely attempting to pass such bans would constitute a win for the planet and its people. That’s because the point of these bills is not just to create new laws. It is also to raise awareness of the issue of over-consumption and the kind of advertisements driving it.

If we’re serious about conservation, ads for wasteful vehicles like SUVs must become history. (Zenel Cebeci, Creative Commons 2.0)

Advocates of advertising bans will need to be smart about their approach. They can make restrictions on advertising more palatable by starting on the local level and targeting a few high-impact product categories. And they can make sure that targeted products have an easily identifiable and limited demographic base.

Rather than starting with fossil fuels, for example, it might be smarter to focus first on fuel-inefficient vehicles. A recent study in the UK found that the richest fifth of households in England are 81 percent more likely to own a heavy-emitting car than those in other income bands. This ratio probably holds for many other product categories. Let’s target them.

Ultimately, a post-growth society will not spell the end of all advertising. In fact, we might see more advertising for things like regenerative enterprises, social non-profits, and other low-impact firms. But to reach that point, we need to shrink the most wasteful sectors of our economy and reduce aggregate production and consumption. Targeting advertisements is an excellent strategy for beginning this crucial work.

Daniel Wortel-London is a Policy Specialist at CASSE.

my comment is on priority of this policy approach.

I think it should take a very back seat to other strategy/tactic

options. Just my take. No wish to extend the discussion here.

Yes, I would rather eliminate the corporations involved in earth destroying operations, then they will produce no ads.

If a ban proves problematic (I’m sure corporations will raise a ruckus about free speech, etc), then I think a pretty good Plan B could be a *tax*.

It shouldn’t be too hard to have a very defensible criteria for a higher tax tier for certain things. I will propose: if peer-reviewed science (in a US context, this could be as determined by a working committee of the Academy of Sciences) determined that a particular class of product or service was probably detrimental to individual health and the public interest, that product or service would be taxed at a higher rate than other things.

Hi y’all

Wishing each and everybody on Earth a wonderful , connecting new year .

My very special thoughts and feelings go to the bad people , those who tend to ruin our planet and keep on doing so … until they are aware of their connection to the rest of us .

Erika

There are 18 minutes per hour of advertising on TV in the U.S. This is ridiculous and a sign of corporate dominance of the culture. We are consumers not citizens. Sources of sales and profit rather than people. What contempt for our time to show us all these ads. How about law to cut hours of ads on the public airwaves? Ads are a huge part of the pro-growth, pro-consumption culture headed towards the cliff.

Hi Daniel, I fully agree that banning advertising of harmful products is a key stepping stone on the path to sustainability. In many jurisdictions green parties have influence occasionally holding powerful influence on coalition govts. A social contract may emerge and spread where it becomes unaccepted and harmful to advertise environmentally destructive items. A soft target starting point may be plastic bottled water and the advertising bans may gain traction from that, spreading elsewhere like smoking bans have done. Such baby steps change the overall mindset maybe leading on to advertising bans on air travel, inefficient vehicles. The ultimate goal which you allude to is seeing the emergence of a social non profit sector competing with one another to deliver a sustainable world, while advertising at us to become responsible for our environmental harm and make sustainable choices. There is so much potential for a swift about turn. Fashion brands with their shallow logos can be replaced with environmental brands which we can embrace and wear. It’s through these types of measures that responsible consumers can identify with, while identifying themselves with one another. A domino effect then has potential as the mirage of the emperors clothes is lifted on shallow consumerist aspirations.