The Economics of Lawns and Landscaping

by Brent Blackwelder

Throughout the United States in urban and suburban settings and in small towns, lawns and massive amounts of non-native flowers, shrubs, and trees dominate the landscape. Such an unhealthy landscape is hardly surprising within an economy obsessed with growth. We lay out grass lawns as fast as possible and throw down landscape arrangements with very little concern for ecological consequences. In contrast, a more thoughtfully designed and ecologically sound landscape fits hand in hand with the framework of a steady state economy.

What’s the Problem with Current Landscape Practices?

The landscaping choices of home and business owners tend to be costly from an economic and an environmental perspective. Around $45 billion is spent annually to care for the 40 million acres of lawns in the U.S., with 800 million gallons of gasoline burned in dirty lawnmower engines. Application of broad-leaf herbicides and high-nitrogen fertilizers for yard maintenance also entails harmful runoff into streams, rivers, bays and estuaries.

Because of the health consequences of chemically laced lawns that are maintained by oil-chugging equipment, a number of organizations such as Beyond Pesticides and SafeLawns have been promoting alternatives. SafeLawns features a slogan, “Time to Get Your Grass Off Gas,” that is particularly pertinent, as the BP spill is the latest in the ongoing oil spills, leaks, and other fiascoes attributable to our dependence on oil.

Of the 220 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions coming annually from off-road vehicles, lawn equipment like mowers and leaf blowers produce about 12% or 26 million tons of the total. Air quality in urban areas can suffer greatly as a result of the dirty motors typically running such equipment.

Importation of non-native species for landscaping causes another set of expensive problems (again from both an economic and an environmental standpoint). And the costly impacts of importing alien ornamental shrubs and trees into the United States have not been explained to the public. There is no way to guarantee that non-native species are free of harmful diseases and insects when they are imported because the host plants may exhibit no symptoms. Once on the loose, it is very hard, almost impossible, to bring the invasive species under control.

The most valuable tree in the eastern U.S. from both a wildlife and commercial timber standpoint — the American chestnut — was almost totally eliminated by the blight from Japanese chestnut trees imported a century ago for the ornamental nursery trade.

This type of disaster has been repeated over the past 100 years with sudden oak death disease, Japanese beetles that entered on Asian nursery stock, the greening disease besetting citrus in Florida, and the soybean aphid that arrived on Asian buckthorns for the ornamental trade — to name just a few.

The staggering price tag for damages caused by invasive species is estimated at over $100 billion per year. Furthermore, 85% of the invasive species have been brought into the U.S. by commercial nurseries. These nurseries suffer no economic consequences for having marketed such exotics that “go astray” and cause millions in damages.

How Would Landscaping Change in a Steady State Economy?

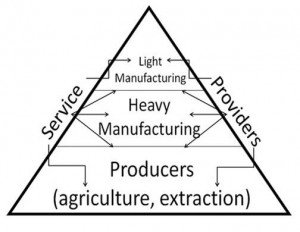

A key feature of a steady state economy is sustainable scale — the economy fits within the capacity of the ecosystems that contain it. Achievement of sustainable scale requires us to value ecological resources and the services they provide. There is a huge opportunity to generate such value by shifting how we manage the landscapes that surround our homes and buildings. Steady state landscapes would enhance biodiversity, improve air quality, and provide food for birds and other wildlife.

Gardening with native species is part of the paradigm shift. The massive harm that accompanies today’s unsustainable landscaping with exotic ornamentals is not reflected in economic calculations. Externalization of such harm would not be part of a steady state economy — an economy that values environmental resources today and in the future.

Professor Douglas Tallamy at the University of Delaware argues in Bringing Nature Home that unless we restore native plants to our yards, the future of biodiversity in North America is dim. Tallamy calls on the public to reevaluate its centuries-old love affair with alien ornamentals and to reverse the practices of the lawn and garden industry in order to provide food for wildlife.

People frequently ask me about tangible actions they can take to move us to a healthier planet. One major opportunity for many is to focus on their own yard or work with their local schools or businesses to shift to landscaping that is a positive force.

If you want to bring back birds and butterflies, you need to have the native vegetation where they can complete their life cycle. In addition to shelter from predators and nesting sites, birds need insects, not seeds or berries, to feed their young. Professor Tallamy asserts: “Birds will not be in our future if we provide them only with shelter and nesting sites.”

What a remarkable result would occur if the $45 billion currently spent on lawn care that degrades biodiversity and causes significant pollution were instead devoted to attractive native landscapes teeming with life!

Well, exactly. Thanks for writing this. The paradigm shift requires a new understanding of the concept of “nature,” as well, I think.

Also, don’t forget the environmental and economic costs of producing plants for the nursery trade far from their point of sale and then trucking them across the country. (Thus did late blight enter and decimate the tomato crop in the Northeast in 2009.) And buckthorn is its very own unique disaster.

One of my other favorite books for the lay gardener is Win-Win Ecology by Dr. Michael Rosenzweig about what he calls “reconciliation ecology,” or designing landscapes for the benefit of non-human species as well as humans. Wild Ones at is another organization that promotes use of native species in landscaping.

In the arid west, the average golf course consumes about a million gallons of water per day. Not sustainable. Palm springs has 18 golf courses. Vegas is starting to use gray water for golf course irrigation. Las Vegas has been sucking Lake Meade dry for years.

For more on water scarcity in the US, see:

http://8020vision.com/2010/06/27/water-scarcity-in-the-us/

It is the second most read article at 8020 Vision.

Jay Kimball

8020 Vision

There is certainly a shortage of native habitat–although what per centage of acreage loss is due to residential areas planted in exotic ornamentals is I think substantially less than that lost to agricultural and ranching activities. I nominate the usual suspect: Too Many People. And Their Accompanying Impacts on Acreage.

Here in Oregon we have a residential area that practices native vegetation only–it’s called Sunriver, and residents are very constrained by the ownership association’s rules as to what can be done in their yards. Basically everything looks continuous and the same–the houses look put down in the native bush with no exotic landscaping or plants, the yards merge into one another with no discernable change. and this is how the original developer wanted it. Rules were implemented from the beginning to keep it that way, and they have.

However, for most people, they don’t want to live in a yard that looks like a native area, because at the scale of a yard that is rather dull, uninteresting, undramatic, overly repetitious. The yards/gardens that are perceived as most beautiful, elegant, & gorgeous are works of art, primarily visually but also in other ways. I’m not sure why exotics are necessary for this, but they seem to be. Yards with only native plants don’t seem to have the same impact. Perhaps this is because beautiful, elegant, gorgeous gardens as works of art have not been designed with native plants only. Perhaps native plant only gardens just haven’t been designed properly yet.

While the reasons for exhorting people to plant only native landscapes around their homes are understandable, we may achieve more actual implementation of this if we also emphasize those plants’ capacity for elegance, beauty, and low maintainence. People are looking for these qualities to surround their homes, as well as being good for wildlife.

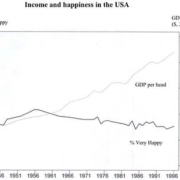

Keep up the good work on the steady-state economy–I’ve been wondering if I may live to see the “contradictions of capitalism” manifest themselves in my lifetime–the analysis of the existence of ‘uneconomic growth’ sounds like one of them, if not a central manifestation! How can the entire globe (‘globalization’) keep returning x% on an ever-increasing base if the base is the entire globe?!

Interesting topic. I’m interested in the psychological and communication issues in conveying consciousness around these issues. Corporate executive approaches to globalization are the basis for the market fundamentalism that blinds most people to such issues.

Colin Beavan’s film, No Impact Man, makes a fine cultural reference point around the related lifestyle issues behind globalization practices. In the film, he pays close attention to agricultural sources of his family’s foods. I would also mention Michael Moore’s film, Capitalism: A Love Story, since he actually arrives at the alternative business model that is the co-operative business model. As a longtime environmentalist, I’ve come to focus on this employee/stakeholder-ownership issue as basic to the cause because of the psychological issues of personal responsibility involved.

Although I’ve been interested in weighing the relative contributions of food co-ops, community supported agriculture, and farmer’s markets, I suspect that each can play important parts in raising the issues of ecological awareness. Brian Halweil wrote a 1997 article on biotechnology, in WorldWatch magazine I think, in which he finishes by discussing agroecology.

I’m glad to have rediscovered CASSE’s site, and look forward to some stimulating threads.

You will spend a long time every week working on your lawn, you need to purchase lawn care equipment like a mower, edger, aerator,

and fertilizer spreader, you simply must purchase “accessories” like gasoline, fertilizer, etc, and you must maintain and store doing this equipment.

General liability insurance and workers compensation needs to

be supplied by the corporation so that in the matter of any sort of accident practical site the responsibiliity of

providing care is clear. They are professionals who can help you in maintaining your backyard

and beautifying it. https://www.felipesoto.net/

The most valuable tree in the eastern U.S. from both a wildlife and commercial timber standpoint — the American chestnut — was almost totally eliminated by the blight from Japanese chestnut trees imported a century ago for the ornamental nursery trade.

(first time I know about this info.)

I like that you talked about achieving sustainable and evaluable ecological resources and services for home and business landscaping needs. I can imagine how this would be important in commercial landscaping, because there would be a huge part of the land that such service will cover. So it would be best for the planet and the environment to be choosing sustainable options instead which might be more affordable for the owners as well.