Steady Statesmanship and Climate Policy in the Midst of a Fascist Threat

By Brian Snyder

The insurrectionist mob that stormed the Capitol last week has been frequently described as fascist. Certainly, it was a far-right, racist mob attempting to overthrow a democratic election, as with the Beerhall Putsch or the March on Rome. Yet, the real fascists in the Capitol weren’t the mob. The actual fascists are far more powerful than a bunch of conspiracy-addled cosplayers. The real fascists were the half-dozen senators and 140 or so representatives who abetted and instigated the insurrection. Furthermore, the real problem in American democracy is not determining how to punish the rabble, but determining how to handle the fascists who’ve infiltrated our American government.

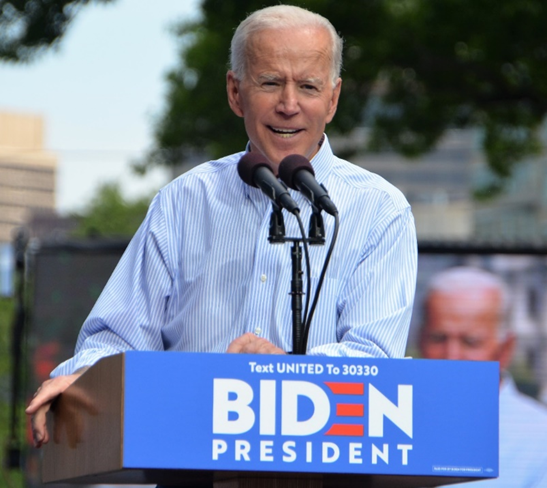

Donald Trump: Conservative or fascist? (Image: CC BY 2.0, Credit: Michael Candelori)

The Mob Was Not Fascist

Do not mistake my argument that the mob was not fascist for sympathy. Quite the opposite. But the difference between fascism and conservatism—even far-right conservatism—is profound. Conservatives believe in democracy; fascists do not. Conservatives and fascists may (or may not) have similar policy preferences, but fascism seeks power through any means—democratic or not. Conservatives, because of their respect for the rule of law, propriety, and precedent, would not seek to abrogate the results of an election. Mitt Romney is a conservative; Donald Trump is better described as a fascist. Of course, this definition seems to suggest that the rioters were fascists. Followers of Trump tried to undermine democracy.

Yet, it would appear that the rioters did not think that they were undermining democracy. They seem to have been deluded into believing that the democratic process had been corrupted and that it was up to them to right that wrong. They saw themselves as democracy’s savior, not its destroyer.

Fascism in the Republican Party

While I do not believe that most of the mob could be fairly called fascists, some members of Congress clearly are fascists, and this should be far more frightening. The mob was enabled by a group of senators and House members who planned to object to the results of free and fair elections in six states. In most cases, they followed through with these objections even after the insurrection. These politicians, all of whom are high-achieving, highly educated individuals, surely knew they were misleading Americans. They knew the elections were fair and that Joe Biden rightfully won, but they did not care. They were willing to trade democracy for power. That makes them nihilists. That the power they sought—another term of Trumpism—was racist, nationalist, and far-right, makes them fascists.

Of course, the Republican Party also has a conservative, non-fascist core centered around Mitt Romney, Mitch McConnell, and a handful of Never Trumpers. At present, it seems like there will be a prolonged dispute within the party between those who will seek power at all costs, and those who believe in democracy. If this conflict occurs—that is to say, if Mitch McConnell is able to rid the party of Trumpism—the mainstream conservatives will win. What they lack in an enthused base, they will more than make up for in corporate dollars, and so a new iteration of the Republican Party may emerge, if not simply revert to the pre-Trump version.

What Now?

In the midst of all of the problems of 2020 and 2021—an attempted coup, racial injustice, a global pandemic, increasing tensions with Iran—we still have all of the problems we had in January 2017 when Donald Trump took office, and most of them are worse. The past 12 months will be the warmest in recorded history—until it is overtaken soon—as global emissions continue to rise. The national debt has ballooned due to the stimuli and tax cuts used to maintain growth. Our geopolitical rivalry with China has deepened, causing concern about a new cold war. The government’s ability to leverage political capital has plummeted as our European allies wonder if we will elect more fascists in the coming years. In just about every way, the USA is worse off than it was four years ago.

Meanwhile, some of us have trouble walking and chewing gum at the same time. Dealing with all of these problems at once will be like riding a unicycle while eating meatloaf. Yet, that appears to be the hand we’ve been dealt, and the consequences if we fail—if we remain divided by race and class, divided on climate and energy, at odds with the world—will be catastrophic. Trump has brought us to the precipice of the abyss, and it is up to Joe Biden to walk us back.

Joe Biden has a task before him unlike any president has faced since 1932; and, as in 1932, the problems we face cannot be solved in a divided, polarized nation. Thus, Biden’s first job must not be climate or economic policy but unity. Unfortunately, Biden can only accomplish something approaching unity with the help of Republicans in the Senate, especially Mitch McConnell.

The unicycle is on a bumpy path when the highest hopes for the Republic rest with Mitch McConnell, yet if anyone in the Democratic Party can work with McConnell, it’s probably Biden.

What Does This Mean for Environmental and Steady-State Policy?

While many of the issues facing the USA are critically important, climate change takes on a special urgency and needs to be addressed immediately. But climate change lacks the immediacy of a pandemic, or insurrection, or a conflict with Iran. As a result, there is a risk that it will be pushed to the back burner. That would be both disastrous and understandable.

Joe Biden: Not a steady-stater, but a symbol for climate stability. (Image: CC BY 2.0, Credit: Michael Stokes)

Further, it is hard to imagine how climate legislation could be passed in a nation so divided. We cannot even agree if our elections are fair or if the President incited a violent mob. How can we possibly agree on a contentious policy that we have argued over for decades?

Yet there is room for a certain degree of optimism. History is instructive. Our nation has been divided in the past: During the late 1960s following the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, the riots following King’s assassination, the Kent State Massacre, the My Lai Massacre, and the police assault during the Democratic Convention in Chicago. Then, as now, domestic terrorist organizations were dedicated to overthrowing the U.S. government from the left (Weather Underground) and the right (the Klan).

Despite these stark divisions, the early 1970s witnessed the passage of nearly every major piece of environmental legislation in U.S. history. The National Environmental Policy Act (1970), the Clean Air Act (extended 1970), the Clean Water Act (1972), and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (1976) were all passed or strengthened during this period and still, five decades later, form the backbone of U.S. environmental policy. Perhaps this was just the culmination of growing environmental awareness, or perhaps it was because passing environmental legislation was easier than dealing with issues of race or war. Whatever the cause, something positive emerged from this great division. Perhaps something similar can happen today.

Perhaps Americans watching this division and hatred will recoil and attempt to build a more community-centered nation, along the lines of that explored in Herman Daly and John Cobb’s For the Common Good. Perhaps they will react against the gilded excess of Trumpism and return to a saner level of personal consumption and debt. Perhaps Americans will begin to understand that they should not rely on their drunk uncle’s Facebook feed as a source of information and return to factual news sources. Or perhaps Americans elect representatives in future elections that make real, substantive change in our political culture, our public policy, or both. If they are looking for a place to start, I might humbly submit the Full and Sustainable Employment Act (FSEA). Indeed, steady-state economics is a curious mix of progressive ideals and conservative values. (What could be more conservative than community-centered, fiscally-conservative conservationism?) The FSEA could make for common ground from which to start.

Brian F. Snyder is an assistant professor of environmental science at Louisiana State University and CASSE’s LSU Chapter director.

Brian F. Snyder is an assistant professor of environmental science at Louisiana State University and CASSE’s LSU Chapter director.

Back in the 30ties and 60ties the organized left wielded real power to push for agendas, this is not the case today after 40 years of neoliberal backlash and center-left giving in to corporate power. The environment is going down from a 1000 cuts watered down from endless compromising w capital and growth politicies and has left climate legislation in most industrialized countries totally inadequate, serving de facto as a coverup for the status quo. The transformation from liberal, enlightened democracies to oligarchic hybrid-states lost of almost all cultural and political external and internal diversity is all but over, and to pin any sort of hope on Biden in any capacity to become the great saviour is downright insane, no offence intended Brian – I’m a firm supporter of steady state echonomics otherwise. I believe Hedges is spot-on here, unfortunately :

https://www.facebook.com/1294099203/videos/10223814390769748/

Much of what you say here is, unfortunately, true enough. However, the way I read Brian Snyder’s article, there’s no hope being placed in Biden to become the “great saviour.” The hope he alludes to toward the end, I think, is in you and I and our fellow steady staters, and our ability to deliver the compelling message of degrowth toward a steady state economy, as well as the policies theretoward. Enough such ability and effort will eventually manifest in politics and policy as well as consumer behavior. No miracles expected.

Point taken, yes I agree after a second read, thx Brian.

Hi Morten, thanks for reading! I agree with your sentiment about the center-left, and I don’t think Biden is a savior but I do hope he represents a transition. I am hopeful that if he gets some of his climate policy implemented, climate policy becomes normalized in the US. Perhaps the next president can then make some more structural changes to the economy. Admittedly, this is nearly blind faith at this point given the events and division of the last week, and it is just as likely that we will slip into something very dark, but that would make for a downer of a post! On the plus side, I see a lot of young people on TikTok who seem anxious for a different economic system, albeit not specifically a steady-state one.

Yes I see you point, and we’re all scared – I know I am scared to death – for my kid, for everything as we’re running out of time fast. Actually I think a preferred/probable scenario to reach critical mass would have been another four years with the neocon Trump – however unbearable – which would have exposed him and doubled the following of an upcoming new green deal type of Sanders leftist many times over (for sure all the young people u mention). If there was/is such a politician, maybe even a steadystater… Same with the rise of the neo-machiavellian right as personified in the ideological gap in the two Bush’es – populist nationalist militarism was off the table as an end to push elitist capitalist agenda after wwii because of first hand evidence. Hopefully the rattling of a dying system will soon be loud enough for everyone to hear and no-one to drown out.

Great article and like the bridge between liberal and conservative, plus the optimism. Only critique is that McConnell deserves no applause. He’s like what we call the 11th hour resistance here in France. For 4 years he enabled the monster, got what he wanted, and now he can dump him. If I were to offer an example of an honest republican, it would be South Carolina conservative Tim Rice, who had the courage to vote for impeachment even though his vote insures that his political career in his Trump-voting district is finished and that he will be getting death threats.

I’m confused. Brian Snyder defined fascism as “fascism seeks power through any means” and yet explicitly excluded McConnell. McConnell has been demonstrating his fascism for years.

Very good point! But I think the desire for power is necessary but not sufficient to call someone a fascist. I think you also need to have a right-wing ideology, and be a nationalist and a racist. I think McConnell is power hungry and a he is to the right of Ronald Reagan, but I am not sure he is a nationalist or a racist, at least to the degree required to call him a fascist. I have no doubt he believes in American exceptionalism, but he is also a globalist. And I don’t think he is racist in the same way much of the right is. That said, as Mark pointed out, abetting a fascist for four years is not a profile in courage.