The Influence of Donella Meadows and Limits to Growth

by Rob Dietz

“There are no limits to growth and human progress when men and women are free to follow their dreams.”

This cornucopian quote sounds like something a Disney character would say, but it’s actually chiseled in stone on a monument in the heart of Washington, DC. These are the words of Ronald Reagan, and they have a permanent home in the atrium of the government building that bears his name. These words also seem to have a permanent home in the economic strategy of the U.S. and just about every other nation.

Reagan’s quote oozes with optimism. His optimistic attitude and his gift for inspiring people formed the core of his popular Presidential style, even if his rhetoric sometimes strayed far from reality. In his quote, he cleverly equated growth (which he championed for political reasons without considering the long-term environmental and social implications) with human progress (which pretty much every voter can get behind).

Reagan’s quote oozes with optimism. His optimistic attitude and his gift for inspiring people formed the core of his popular Presidential style, even if his rhetoric sometimes strayed far from reality. In his quote, he cleverly equated growth (which he championed for political reasons without considering the long-term environmental and social implications) with human progress (which pretty much every voter can get behind).

One prominent public figure was able to match Reagan’s hopefulness and ability to inspire. She was a humble writer and farmer, but first and foremost, she was a scientist who rooted her analyses in the laws of physics and ecology (she certainly never tried to gain support by resorting to fantasy-land notions such as infinite growth on a finite planet).

When Donella Meadows passed away suddenly in 2001, humanity lost a leading light. If you begin reading her Global Citizen columns, it’s hard to stop before you’ve read through the entire 16-year archive. With wit, style, and uncommon insight, she tackled some of the most pressing social and environmental problems, and her writing was so good that the column was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. She became one of the most influential people to promote the vision of a sustainable society. In fact, the Post Growth Institute has ranked her at number 3 (right behind E. F. Schumacher and Herman Daly) in their list of the top 100 sustainability thinkers.

Meadows became internationally famous in 1972 as the lead author of The Limits to Growth, a little book with powerful ideas that went against the mainstream grain. She and her coauthors, Dennis Meadows, Jorgen Randers, and William Behrens, combined principles from the emerging field of system dynamics with newly developed computer modeling capabilities to assess the implications of ongoing growth in population, food production, industrial output, pollution, and consumption of nonrenewable resources. Even the most biting critic has to admire their guts and resolve for undertaking such an ambitious study to build a robust model of the world!

It’s hard to overstate the influence of The Limits to Growth, which was translated into 25 languages and became the best-selling environmental book of all time. That’s a stunning achievement on its own, but it’s all the more impressive for a book that covers such a disconcerting topic by presenting a bunch of output from a computer model.

It’s hard to overstate the influence of The Limits to Growth, which was translated into 25 languages and became the best-selling environmental book of all time. That’s a stunning achievement on its own, but it’s all the more impressive for a book that covers such a disconcerting topic by presenting a bunch of output from a computer model.

The book’s level of influence can be demonstrated by three pieces of evidence beyond the sales figures. The first piece of evidence comes from the realm of politics. Jimmy Carter, a scientist and farmer like Meadows, was clearly inspired by her work and that of other like-minded scholars (he even hosted E. F. Schumacher at the White House). In his “Crisis of Confidence” speech (1979), Carter called for conservation of energy, sharing of resources, and pursuit of meaning through channels other than “owning things and consuming things.” That sounds a lot like a practical and hopeful approach to dealing with the limits to growth. But Carter’s political rivals re-branded his speech as the “Malaise Speech.” They successfully undermined his message, which was seen as a threat to corporate power and unchecked economic growth.

The second piece of evidence is closely related to the backlash heaped on Carter, which helped sweep him out of office and set the stage for the era of reckless Reaganomics. The Limits to Growth received the same backlash as Carter, and as Richard Heinberg reports, detractors took such strides to discredit the book that millions of people mistakenly believe it was debunked years ago. This is nonsense — the book’s analysis and its underlying message have held up surprisingly well. In fact, in 2008 the Australian Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization took a close look at the book’s scenarios. The findings show that thirty years of historical data compare favorably to key features of the book’s business-as-usual scenario (ominously, this scenario results in collapse of the global economic system sometime around 2050. The fact that The Limits to Growth struck such a nerve and raised the ire of so many critics serves as a potent reminder of its influence.

The third piece of evidence is anecdotal. I bought my own copy of The Limits to Growth (a 1975 second edition) from a used book store a few years ago. The book’s original owner received it as a Christmas present from someone named Rex. In his “Merry Christmas” note on the inside cover, Rex wrote, “I haven’t read this yet, but it’s supposed to contain some interesting ideas on where we are heading.”

Meadows and company summarize “where we are heading” right up front by stating these three far-reaching conclusions:

- If the present growth trends in world population, industrialization, pollution, food production, and resource depletion continue unchanged, the limits to growth on this planet will be reached sometime within the next one hundred years. The most probable result will be a rather sudden and uncontrollable decline in both population and industrial capacity.

- It is possible to alter these growth trends and to establish a condition of ecological and economic stability that is sustainable far into the future. The state of global equilibrium could be designed so that the basic material needs of each person on earth are satisfied and each person has an equal opportunity to realize his individual human potential.

- If the world’s people decide to strive for this second outcome rather than the first, the sooner they begin working to attain it, the greater will be their chances of success.

Detractors of The Limits to Growth clearly had an agenda — they didn’t want any obstacle to impede their quest for unlimited profits and accumulation of wealth. But Meadows and company had an agenda, too. Their agenda, revealed in the second concluding point, is profoundly humanitarian. They were desperate to find a way to maintain human well-being without undermining the life-supporting systems of the planet.

Unfortunately, even to this day, the anti-limits marketing machine continues to churn out propaganda and sway public opinion toward the wishful thinking of infinite growth. We are not going to achieve infinite economic growth on planet Earth. Not only is it physically impossible, but it’s also an undesirable goal to begin with.

We’ve made disappointing progress on the third concluding point of Meadows and company over the last forty years. Even so, their premise still holds. The sooner we begin working toward a steady state economy, the greater our chances of providing a lasting prosperity for all of civilization.

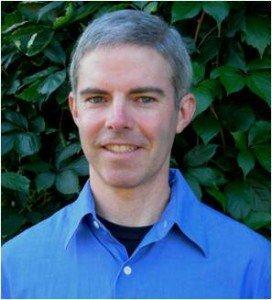

Rob Dietz brings a fresh perspective to the discussion of economics and environmental sustainability. His diverse background in economics, environmental science and engineering, and conservation biology (plus his work in the public, private, and nonprofit sectors) has given him an unusual ability to connect the dots when it comes to the topic of sustainability. Rob is the author, with Dan O’Neill, of Enough Is Enough: Building a Sustainable Economy in a World of Finite Resources.

Rob Dietz brings a fresh perspective to the discussion of economics and environmental sustainability. His diverse background in economics, environmental science and engineering, and conservation biology (plus his work in the public, private, and nonprofit sectors) has given him an unusual ability to connect the dots when it comes to the topic of sustainability. Rob is the author, with Dan O’Neill, of Enough Is Enough: Building a Sustainable Economy in a World of Finite Resources.

"Rappahannock County Courthouse" by taberandrew is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

"Rappahannock County Courthouse" by taberandrew is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

It is interesting to see that critics (mostly economists) of the idea that there are limits to growth almost always refer to The Limits to Growth, trying to suggest that it has been proved wrong by history (“The world hasn’t collapsed, has it?”). As I once wrote on my blog, it is a kind of upright obsession. A seldom one, since they tend to oversimplify Meadows et al.’s and ignore all other arguments that support the limits to growth hypothesis.

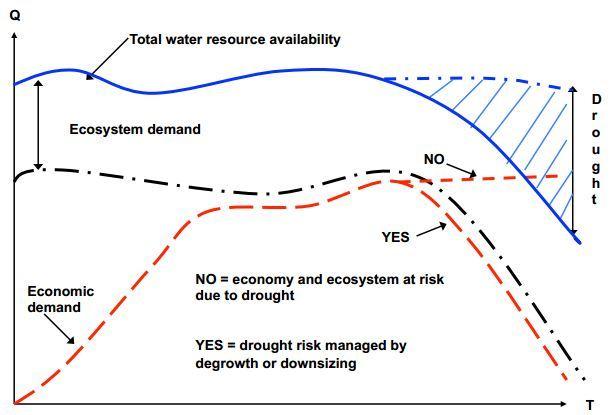

I believe Meadow’s book, Thinking in Systems has the capacity to transform how people are able to think and therefore transform society. I have about 20 tabs in that book to identify key points that I can refer to as I develop an ecocommerce model. My recent epiphany related to systems is an ecocommerce concept I called “symbiotic demand”. I converts the “tragedy of the commons” into an economic opportunity that addresses the self interests of land managers and corporations that depend on a functioning natural capital base: https://prezi.com/tpfaewgz1jie/apportioning-ecological-values-and-costs-through-symbiotic-demand/

I have also recently recognized that as people search for ecological economics solutions, they have a tendency to subconsciously believe that a solution to address the externalities of our capitalistic economy will not emerge – with economists being the best at being dismal.

There are a couple of problems which prevent scenario 2 from happening in the current circumstances.

First: the blind belief that humans work intentionally, rather than randomly and emotionally (sense-response rather than think-do).

Second: the ignorance of our animal natures of competitiveness and the loss of natural moderating systems which humanists cannot fathom putting back in place (death panels, if you will).

We worry about the robots taking over the world, but humans have become robots: consumer-producer robots that do not follow a path toward their future best interests. “Limits to Growth” makes the assumption that the current species of human is something OTHER than the animal which it evolved to be.

Nice Article. Thank you for sharing.