Modernizing Henry George

by Herman Daly

Economists have traditionally considered nature to be infinite relative to the economy, and therefore not scarce, and therefore properly priced at zero. But the biosphere is now scarce, and becoming more so every day as a result of growth of its large and dependent subsystem, the macro-economy. As the macro-economy expands into the ecosystem it displaces what was there before, namely habitat of other species (and of indigenous and poor members of our own species). Consequently, biodiversity decline is a salient index of the increasing scarcity of nature, as is involuntary resettlement of people to make way for dams, mines, soybeans, and cattle; and of course increasing depletion and pollution. Sacrifice of nature’s scarce services constitutes an increasing opportunity cost of growth, and that in turn means that nature must be priced, either explicitly or implicitly. But to whom should this price be paid? Nature would prefer not to sell herself, but if forced to it by growth, would at least like to divide equally among her children the revenue from the forced sale of her previous gifts. From the point of view of efficiency it does not matter who receives the price, as long as it is counted and paid by the users. But from the point of view of equity it matters a great deal who receives the price for nature’s increasingly scarce services. Such payment is the ideal source of funds with which to finance public goods, and to redistribute to the poor.

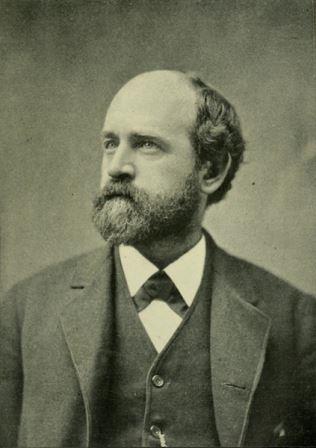

Why do we not take the ideas of Henry George and apply them to natural resources? (Image: CC0, Credit: Unknown)

“Value added” belongs to whoever added it. But the original value of that to which further value is added by labor and capital, the value of scarce natural resources and natural services, should belong to everyone. It is the original commonwealth. These “payments to nature” should be the focus of redistributive efforts. Payment for what is now too scarce to be treated as a free gift is measured and appropriated by markets as a rent (payment in excess of necessary supply price). Rent is unearned income to the recipient, but allocative efficiency requires that it be paid by the user of the resource. Taxation of value added by labor and capital is certainly legitimate. But it is both more legitimate and less necessary after we have, as much as possible, captured natural resource rents for public revenue.

The above seems to be the basic insight of early American economist Henry George (1839-1897) who applied it specifically to rent on the scarcity of desirable locations of land rather than to rents on natural resource scarcity in general. Could we not extend Henry George’s logic to resources in general? For resources the necessary supply price is the cost of extraction—so any payment above cost of extraction is rent. Since land has no cost of extraction all payment for land is rent. If no rent is paid, land does not cease to exist. Neoclassical economists accept this definition of rent but resist Henry George’s ethical emphasis on rent as unearned income.

The modern form of the Georgist insight is to tax the rent from land, and by extension from natural resources and services of nature, and to use these funds for fighting poverty and for financing public goods. Or we could simply create a trust fund from these rents, and disburse the earnings from it to all citizens, as in the Alaska Permanent Fund. Our present practice of taxing away a lot of the value added by individuals from applying their own labor and capital creates resentment, and discourages the supply of labor and capital. Taxing away value that no one added, scarcity rents on nature’s contribution, does not create as much resentment, and the resentment it does cause is less justified. In fact, failing to tax away the scarcity rents to nature and letting them accrue as unearned income to a landlord class has long been a primary source of resentment and social conflict. Furthermore, taxing land and resource rent does not diminish their quantity. Soviet communists tried for a while to abolish the category of rent because it represented unearned income—a part of “surplus value” like profit and interest. They jumped to the conclusion that therefore resources and land must be free. But that makes it impossible to allocate resources efficiently. Better to follow Henry George and retain rent as a necessary price for measuring opportunity cost, but to then tax it away as unearned income to the landlords. The more we tax away rent the less we have to tax the value added by human labor and capital.

Charging scarcity rents on natural resources and redistributing them to the commonwealth can be effected either by ecological tax reform, or by quantitative cap-auction-trade systems. In differing ways each would limit expansion of the scale of the economy into the biosphere, thereby preserving biodiversity and also providing revenue to run the commonwealth. I will not discuss their relative merits here, but rather emphasize the advantage that both have over the currently favored strategy. The currently favored strategy might be called “efficiency first” in distinction to the “frugality first” principle embodied in each of the policies mentioned above.

“Efficiency first” sounds good, especially when referred to as “win-win” strategies, or more picturesquely as “picking the low-hanging fruit.” But the problem of “efficiency first” is with what comes second. An improvement in efficiency by itself is equivalent to having an increased supply of the resource whose efficiency increased. The price of that resource will decline. More uses for the now cheaper resource will be made. We will end up consuming perhaps as much or more of the resource than before, albeit more efficiently, as pointed out in the nineteenth century words of economist William Stanley Jevons:

“It is wholly a confusion of ideas to suppose that the economical [efficient] use of fuel is equivalent to a diminished consumption. The very contrary is the truth.” (The Coal Question, 1866, p. 123)

If we keep refusing to pay Nature’s rent, our home could like this. (Image: CC BY 2.0, Credit: Crustmania)

We need frugality (diminished consumption) more than efficiency. “Frugality first” induces efficiency as a secondary consequence, an adaptation; efficiency first does not induce frugality—it makes frugality less necessary, and it does not give rise to a scarcity rent that can be redistributed. Let us put frugality first by reducing physical throughput with ecological tax reform and/or cap-auction-trade systems for basic resources, and by so doing both avoid the Jevons effect and collect the scarcity rents on nature for the commonwealth rather than the elite.

If we could directly limit population and per capita resource use (scale of the macro-economy) to a level that nature could easily sustain, then nature’s services could remain free. But if we insist that population and per capita consumption must be free to grow, then the rising cost of natural resources must indirectly limit growth, and the question of who receives the increasing rent (who owns nature) will become ever more pressing, and Henry George’s thinking ever more relevant. Alternatively, our increasing takeover of nature will, beyond some point, render moot the question of distribution of rents by eliminating all potential claimants! When an overloaded ship sinks all aboard drown—even if the overload is justly distributed and efficiently allocated!

Herman Daly is CASSE’s Chief Economist, Professor Emeritus (University of Maryland), and past World Bank senior economist.

Herman Daly is CASSE’s Chief Economist, Professor Emeritus (University of Maryland), and past World Bank senior economist.

Bravo, well written. My thoughts exactly. I call it “voluntary austerity”. Without it, population overshoot and the attending resource depletion (manifesting themselves at present) will bring “our moment in the light” to an end and thrust us back into the darkness of post empire yet again. Mankinds collective memory is ever so short.

By coincidence, Martin Wolfe and the Financial Times are also reconsidering Henry George. Maybe ecological tax reform isn’t that far removed from the mainstream:

http://blogs.ft.com/martin-wolf-exchange/2010/07/12/why-were-resources-expunged-from-neo-classical-economics/

Daly is 100% correct THEORETICALLY, but he completely ignores the problem of how LVT (land value taxation) is to be politically implemented. It must be done GRADUALLY but he does not address that problem at all

Herman Daly wrote:

Economists have traditionally considered nature to be infinite relative to the economy, and therefore not scarce, and therefore properly priced at zero.

Ed Dodson here:

While this observation can be found in the writings of some economists, the number of economists who embrace public policies that would achieve this result is quite small. I am reminded of what the economics professor Harry Gunnison Brown wrote at the beginning of his textbook on economics published during the 1940s and 1950s. He titled this first chapter, “Prejudice Versus Science,” and the reader could not be misconstrue his meaning:

“Economics is concerned with the problem of ‘getting a living.’ It deals, therefore, with an important phase of the ‘struggle for existence.’ Unfortunately, this fact operates to prevent unprejudiced investigation of its laws and of the effects of various economic policies. An examination that would would show the effects of various policies from which a part of the public was benefiting, to be injurious to the remainder, might not be an examination which those who were profiting by the policies in question would desire to have made. And if such an examination were made, acceptance of its inevitable logical conclusions would probably be vigorously opposed. …Economic theories are, in effect, voted on, when policies involving them are adopted or rejected. But the bias which economics has to face, so far as it is not merely the inertia of ignorance, is a bias of special and class interest and of political affiliation, rather than of theological outlook.”

Brown is certainly not the only member of his profession to express frustration over the undue influence of vested interest over the objective pursuit of scientific knowledge; but, teaching the history of economic thought, I find his perspective very instructive.

***

Herman Daly wrote:

… biodiversity decline is a salient index of the increasing scarcity of nature, as is involuntary resettlement of people to make way for dams, mines, soybeans, and cattle; and of course increasing depletion and pollution.

Ed Dodson here:

Is this real or contrived scarcity? Our footprint is so heavy on the earth’s life-support systems in large part because we are spread out over the globe. Our pattern of resource extraction is wasteful and unncessarily destructive because government’s subsidize short-run profit-maximizing methods of exploitation. What if we constructed our own communities at densities similar to that of the Netherlands and not permitted population and infrastructure to sprawl across the landscape?

***

Herman Daly wrote:

Sacrifice of nature’s scarce services constitutes an increasing opportunity cost of growth, and that in turn means that nature must be priced, either explicitly or implicitly.

Ed Dodson here:

Is it “nature” that must be price, or “access to nature”? This may not seem like an important distinction, but because this distinction has been lost (since Locke argued its importance) our system of law has sanctioned the private ownership of nature (i.e., of the commons) rather than provide for a competitive leasehold system such as proposed by Henry George before settling on the taxation of rent as a substitute approach.

***

Herman Daly wrote:

… From the point of view of efficiency it does not matter who receives the price, as long as it is counted and paid by the users. But from the point of view of equity it matters a great deal who receives the price for nature’s increasingly scarce services. Such payment is the ideal source of funds with which to finance public goods, and to redistribute to the poor.

Ed Dodson here:

Efficiency actually suffers quite considerably, as users of nature under current conditions are forced to pay both the owners of land for access, then must pay taxes to government to provide for public goods and services. The landed also pay taxes but do so out of the rents they have privatized.

***

Herman Daly wrote:

… These “payments to nature” should be the focus of redistributive efforts.

Ed Dodson here:

Consider a different definition of rent, as society’s rightful claim on the physical wealth produced by labor with the assistance of capital goods. By this definition, the private appropriation of rent is redistributive (i.e., from producers to nonproducers). The rightful distribution of rent, then, is to all members of a community or society.

***

Herman Daly wrote:

Rent is unearned income to the recipient, but allocative efficiency requires that it be paid by the user of the resource. Taxation of value added by labor and capital is certainly legitimate. But it is both more legitimate and less necessary after we have, as much as possible, captured natural resource rents for public revenue.

Ed Dodson here:

We can agree that rent, when privatized, is unearned to its recipient. And, so long as the holder of a deed is able to charge others for access under a leasehold arrangement, the landowner collects the rent payment from the tenant. However, there is no economic value added by the landowner as landowner.

***

Herman Daly wrote:

The above seems to be the basic insight of early American economist Henry George (1839-1897) who applied it specifically to rent on the scarcity of desirable locations of land rather than to rents on natural resource scarcity in general. Could we not extend Henry George’s logic to resources in general?

Ed Dodson here:

Henry George had a pretty solid handle on resource rents and wrote extensively on the need for allocation of resource-laden lands by competitive bidding to recoup the full amount of rents for the public. He knew that many of his predecessors and contempories also grasped these principles but had ignored the dynamics of urban land markets, so this is where he focused a good deal of his efforts.

***

Herman Daly wrote:

For resources the necessary supply price is the cost of extraction — so any payment above cost of extraction is rent. Since land has no cost of extraction all payment for land is rent. If no rent is paid, land does not cease to exist. Neoclassical economists accept this definition of rent but resist Henry George’s ethical emphasis on rent as unearned income.

Ed Dodson here:

I believe it is clearer to say there is a zero cost of production for nature in terms of labor and capital goods. Extraction of minerals, timber and other natural resources does have a cost — in terms of labor and capital goods. If we assume public control over all such locations, access to which is awarded under leaseholds acquired by competitive bidding, then the rents obtained will represent what the most efficient resource extractor will bid based on the cost of extraction as against market prices for the commodities produced.

***

Herman Daly wrote:

The modern form of the Georgist insight is to tax the rent from land, and by extension from natural resources and services of nature, and to use these funds for fighting poverty and for financing public goods. Or we could simply create a trust fund from these rents, and disburse the earnings from it to all citizens, as in the Alaska Permanent Fund.

Ed Dodson here:

I may be mistaken, but I believe the contributions to the Alaska Permanent Fund are not determined by calculating rents but by charging a royalty on the value of oil taken.

***

Herman Daly wrote:

Our present practice of taxing away a lot of the value added by individuals from applying their own labor and capital creates resentment, and discourages the supply of labor and capital. Taxing away value that no one added, scarcity rents on nature’s contribution, does not create as much resentment, and the resentment it does cause is less justified. In fact, failing to tax away the scarcity rents to nature and letting them accrue as unearned income to a landlord class has long been a primary source of resentment and social conflict.

Ed Dodson here:

In the United States, at least, the opportunity to become wealthy by speculating in and hoarding land has a long and cherished history. Despite the volatility of land markets and the periodic crashes that (as is happening now) result in deep economic and social dislocations, the potential to acquire a residential property that will “appreciate” in value over time is sought after as a major source of net worth and income for retirement. Thus, despite the powerful ethical and efficiency arguments to support a shift to the taxation of location rental values, exempting property improvement values, local governments have tended to turn to this approach only when their economies are in disarray and there is no other option for raising enough revenue to provide basic public goods and services. In these instances, the landowners who often end up with the increased tax bills are absentee corporate owners who have abandoned their facilities. There have been exceptions (e.g., Sydney, Australia) but the U.S. experience in cities with relatively strong economies is that landed interests prevail when property tax reform is attempted.

***

Herman Daly wrote:

Furthermore, taxing land and resource rent does not diminish their quantity. Soviet communists tried for a while to abolish the category of rent because it represented unearned income — a part of “surplus value” like profit and interest. They jumped to the conclusion that therefore resources and land must be free. But that makes it impossible to allocate resources efficiently. Better to follow Henry George and retain rent as a necessary price for measuring opportunity cost, but to then tax it away as unearned income to the landlords. The more we tax away rent the less we have to tax the value added by human labor and capital.

Ed Dodson here:

Some of us tried to make the “Henry George case” with Russian officials back in the 1990s. In a paper I delivered before the Russian Duma in 1996, I argued that Russia was in the unique position of avoiding the speculation-driven boom-to-bust property markets experienced here in the West by retaining public ownership of land but offering it to private interests under leaseholds awarded by competitive bidding. More powerful voices than mine (e.g., Mason Gaffney of the University of California and Nic Tideman of Virginia Tech) tried to make the case but influential Russians were already hard at work creating their own landed class.

***

Herman Daly wrote:

If we could directly limit population and per capita resource use (scale of the macro-economy) to a level that nature could easily sustain, then nature’s services could remain free. But if we insist that population and per capita consumption must be free to grow, then the rising cost of natural resources must indirectly limit growth, and the question of who receives the increasing rent (who owns nature) will become ever more pressing, and Henry George’s thinking ever more relevant. Alternatively, our increasing takeover of nature will, beyond some point, render moot the question of distribution of rents by eliminating all potential claimants! When an overloaded ship sinks all aboard drown — even if the overload is justly distributed and efficiently allocated!

Ed Dodson:

Although Henry George argued there was no direct relation between population size and poverty, he recognized that without many changes in our socio-political arrangements and institutions poverty would continue to plague humanity, as it has. What he tried to warn us is that absent the public collection of rent all of the other measures we might employ would fail. The final chapter of his book ‘Protection or Free Trade’ discusses this point with respect to the outcome of removing all barriers to trade.

You seem to say that, if we use land more efficiently, we will use more of it. But with land rent uncollected, many owners use far more land than they need, hoping to profit from increase in selling price. If big box stores had to pay the full rental value of the land used for their parking lots, would they not consider ways to do business more compactly?

Excellent piece. Populations would tier downwards if we had a scarcity based tax system where everyone paid their fair share. With less leakages we would have more finance for women’s education and decent health.

Supply side economics must be replaced by an understanding of scarcity rents. Land values are like a giant oil well – they are the most sustainable of all resources and must be shared. When properly implemented, property bubbles are avoided – we grow up not out.

I like this argument because we can attract business with lower company and indirect taxes.

The everyday person must switch onto the tax game so we can call the pyramid purveyors to order.

The Jevons quote immediately conjured up recollection of Ford’s slogan ‘EcoBoost [sic] offers the thirst of a V6 with the thrust of a V8.’ Obviosly that’s Eco as in economy (efficiency) not ecology. When I first saw the Ford commercial, my immediate gut-level reaction was of course disgust. Is there some reason the same technology cannot be used to create an engine with, say, the thirst of a 4-cylinder engine with the thrust of a V6, or better yet, the thrust of a 4-banger with the thirst of a lawn mower engine? Assuming there is, is that reason yet another engineering tradeoff whose envelope happens to be most pushable in the performance car end of the curve, or is it yet another Iron Law of Economics (Sociology?) to the effect that the American consumer is inveterately maximalist, and whose accelerator pedal can be pried away, perhaps, from their cold, dead toes.