The Hidden Door

by Mark Burch

This excerpt is from Mark Burch’s new book, The Hidden Door: Mindful Sufficiency as an Alternative to Extinction.

This excerpt is from Mark Burch’s new book, The Hidden Door: Mindful Sufficiency as an Alternative to Extinction.

A few years ago, I participated in a practice called kirtan, a form of call and response singing conducted as a meditative practice. Its purpose is to create joy. One evening the lead singer introduced a chant in English, instead of the customary Sanskrit, with the words: “I can see a door hidden in the wall.”

The image of a door hidden in a wall is one that has stayed with me. For me, it’s a metaphor for the survival challenge humanity now faces. It expresses a sense of the forcible confinement into which consumer culture has brought us. But it also expresses the hope that an exit exists — if only we can find it.

In my imagination, the confining wall is the whole of consumer culture. It is a culture, even though individuals and institutions stand in its defense. Consumer culture is also a cell the walls of which are closing in on us, driven forward by many forces, the most important of which are psychological. Now they are crushing many beings including us.

I believe the door in the wall to be voluntary simplicity, or what I have come to think of as mindful sufficiency. I’m not the discoverer of this way of life. Neither did I author its perspective of the good life. But I’ve been its avid student for half a century, and in that time and through personal experience I have come to believe that it represents a doorway to life flourishing in a situation that otherwise promises our extinction.

The door leading from extinction to renewed life is hidden in the same sense in which some Buddhists describe their doctrines as “self-secret.” They are truths hidden in plain sight because seeing them requires a change in the seer. When we change, then the way to the exit is obvious, but until we change, it remains hidden.

A considerable literature has appeared about voluntary simplicity. A great deal of it recycles the same advice about ways individuals can simplify how they live. Far less common are treatments that penetrate the deeper structure of values and meaning that constitutes the DNA of voluntary simplicity. What sort of culture might appear if we took seriously the essential values and principles that constitute simple living and let them inform a new perspective of the good life? What might happen if we extended this outlook from individual lifestyle choice to an agenda for cultural renaissance? The Hidden Door aims to make a contribution to such a process by exploring topics not usually addressed in the existing simplicity literature.

Voluntary simplicity is a way of life. It is a philosophical outlook as well as an aesthetic and a spiritual sensibility. Some might say it’s also a direction for cultural and technical development that calls for its own politics, its own economic institutions, and its own creative process.

I’ve come to believe that both the source and the destination of simple living is the cultivation of mindfulness. I see it as the first strand in the DNA of simplicity. Others who write about simple living may have differing views on the matter or may give mindfulness a different priority in their hierarchy of values. But in my study and experience mindfulness is a perennial theme in the history of simple living, in the accounts of those who love simple living, and a mental discipline, the development of which is central to a good life.

The second strand in the DNA of simplicity is the principle of sufficiency. In simple living, the value of sufficiency replaces consumer culture’s obsession with avarice and affluence. The value of sufficiency arises from a radically different understanding of what material consumption contributes to a good life. It would be shortsighted to deny that consumer culture offers many pleasures. But what is mostly missing from its menus are the longer term costs incurred by luxury indulgences.

Mindfulness and sufficiency together form the essential braid of voluntary simplicity’s DNA. They spiral around each other, lending this way of life its dynamic, structure, and direction. With these in mind, we can then explore a number of considerations central to a culture of simple living. We might think of these other topics as base-pairs that bridge between the spiral strands of mindfulness and sufficiency, relating them to each other in specific ways, enabling their synergy, and offering at least a partial anatomy of an alternative to consumer culture.

I can imagine a great many such bridges. We should explore them all. In what follows, I make a beginning by discussing five of them:

“Communicating Simplicity” begins from the observation that once we discover the value of mindfulness and sufficiency, a natural impulse is to share this experience with others. This process is inherently relational and implies community. It also implies opting for certain ways of communicating and leaving aside others.

Discussion of communication evolves naturally toward the subject of “Educating for Simple Living.” To manifest a way of life which is materially simple but culturally and spiritually rich requires deliberate attention to learning what exactly it is that empowers people to secure an ever greater measure of well-being on an ever more modest expenditure of energy, resources, and labour.

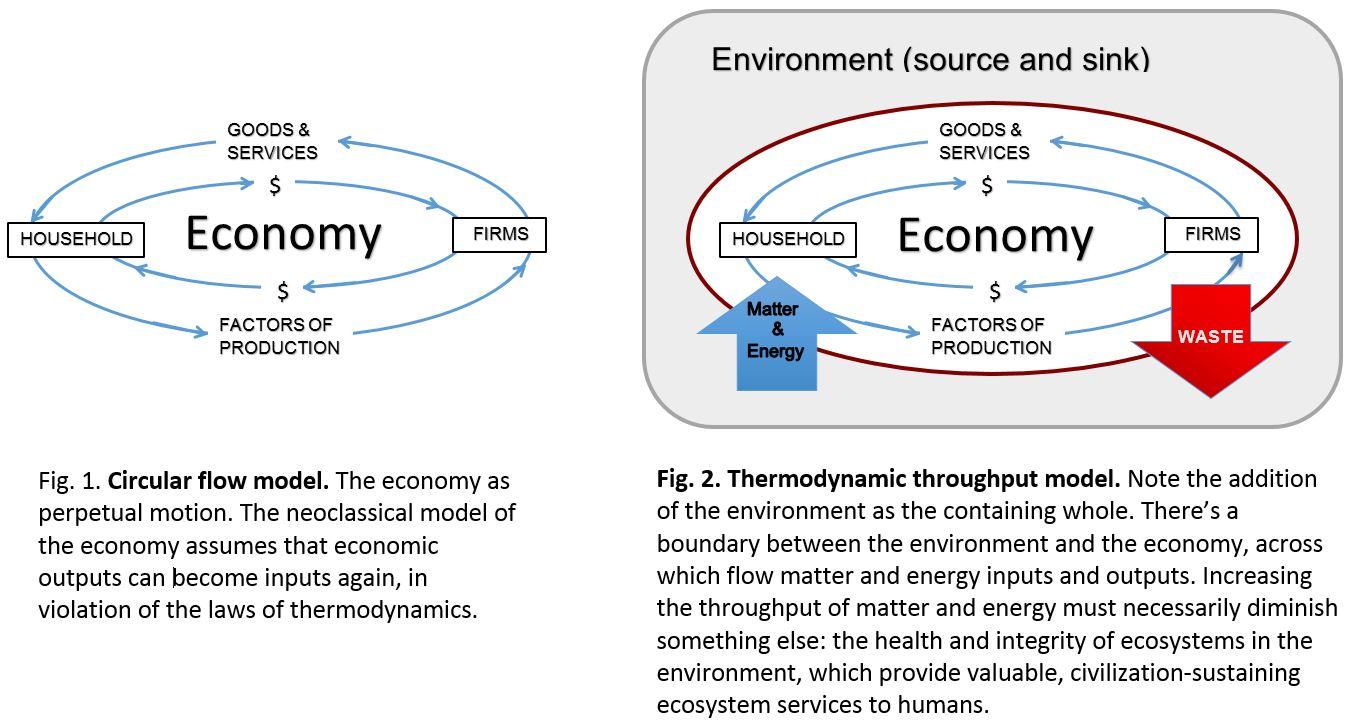

“Simplicity and Economy” takes up the question of what an economy might look like if it was oriented around the values of mindfulness and sufficiency rather than the oppressive promotion of consumerism and economic growth.

Today, it is almost impossible to discuss economics without also considering technology. “Technology and Simplicity” explores what role technology might play in a culture of simple living. Bringing mindfulness to our use of technology leads to insights about how the social and economic roles of technology might change if technology was oriented to serve simple living rather than consumerism and private profit.

Finally, the good life aims to increase human well-being. To me the concept of well-being is inextricably linked with that of human rights. In “Simplicity, Sustainability, and Human Rights,” I argue that consumer culture — traditionally portrayed as the most successful pathway to increasing well-being and protecting human rights — is in fact the single greatest threat to them and that conserving our rights and promoting well-being is highly unlikely apart from a culture of simple living.

Voluntary simplicity is the door hidden in the impregnable wall of our cultural blindness and inertia. I believe it is our single best hope for thriving into the deep future.

—

Mark Burch is an author, educator, and group facilitator who has practiced simple living since the 1960s, and since 1995, offers presentations, workshops and courses on voluntary simplicity. He is a fellow of the Simplicity Institute and also the author of Stepping Lightly: Simplicity for People and the Planet.

Not to be mssed

And it seems the opposite is true, perhaps a chicken/egg prerequisite – that a degree or experience with simplicity catalyzes a degree of mindfulness. Much of my career has involved taking adolescents and adults into the wilderness for 20 plus days of very “simple” living, and I’ve noticed that there is, for many if not most, an ongoing shift in values and desires. That is – even years later, of the participants I’ve been in contact with, while there is usually a continued participation in the consumer culture (it’s kinda like a tar-baby – pretty hard to step out of when all of ones family and friends remain), there is an evident lack of enthusiasm, and a strong tendency toward intellectual and emotional development instead of material accumulation.

A nice article, with good images to contemplate!