Where Does Inflation Hide?

by Herman Daly

The talking heads in the media explain the recent fall in the stock market as follows:

A fall in unemployment leads to a tight labor market and the prospect of wage increases; wage increase leads to the threat of inflation; which leads the Fed to likely raise interest rates; which would lead to less borrowing, and to less investment in stocks, and consequently to an expected fall in stock prices. Therefore investors (speculators) rush to sell before the expected fall in stock prices happens, bringing about the very fall expected. So, the implicit conclusion is that rising wages of the bottom 90 percent are bad for “the economy,” while an increase in the unearned incomes (lightly taxed capital gains) of the top ten percent is good for “the economy.” The financial news readers of the corporate media avoid making that grotesque conclusion explicit, but it is implicit in their explanation.

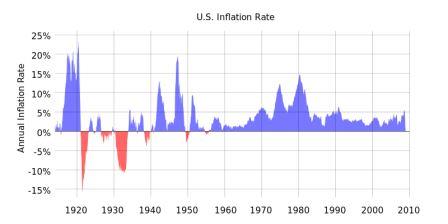

US Inflation Rate Since 1914 (Image: CC0 1.0 Universal, Credit: Department of Labor / Bureau of Labor Statistics)

A wage increase, in addition to cutting into profits, is considered inflationary, and that leads the Fed to raise interest rates and choke off the new money feeding the stock market boom and related growth euphoria. But higher interest rates serve other functions, most notably to keep capital from being wasted on uneconomic projects that are financially lucrative only at zero or negative interest rates. Furthermore, positive interest rates reward savers provide for retirement and emergencies and even reduce the inflationary effect of consumer spending.

As long as officially measured inflation is low the Fed can keep on pushing money into the economy to finance the asset boom. But why, with so much added money has there apparently been so little measured inflation? In truth, there has been a lot of inflation, but it has simply not been measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Why is that? Because the new money is borrowed into existence by investors who use it mainly to buy existing assets (stocks, bonds, real estate, art, crypto-currencies, etc.). The price of assets goes up; we have asset price inflation, but asset prices are not part of the CPI and go uncounted. Inflation occurs in asset prices rather than in consumer goods prices, leading to boom and bust cycles.

Some inflationary pressure spills into the goods markets but does not register directly as a price increase and thus goes uncounted. Examples are numerous. At the supermarket the price stays the same while the box of raisins gets smaller, the block of cheese shrinks, the cup of yogurt is less full, the self-checkout line becomes the only option, etc. Airfares may not go up, but seat space declines; “miles” become ever more difficult to redeem, and quality of service becomes aggressively bad. Everywhere customer service declines as recorded “answers” replace real people (“your call is important to us—please stay on the line”). Our premier newspaper, The New York Times, may not raise its price, but it repeats the identical articles over and over after day and in various sections of the same edition. The price to watch network TV is to endure the commercials, which keep getting longer and louder. In sum, quantitative easing has resulted in unmeasured inflation, mainly in the asset market, but also in the consumer goods market.

Federal banks are meant to serve the public, yet member banks hold stocks in them. How can we hold the Fed accountable as an independent entity? (Image: CC BY-SA 2.0, Credit: Ken Lund)

Economists at the Fed are not stupid—they know this. Why then do they not correctly measure inflation and stop quantitative easing and the resulting zero (or even negative) interest rates? Because the increase of asset prices benefits the asset owners, the rich, while the smaller rise in the undercounted CPI hurts mainly the poor. Also, under our fractional reserve banking system, new money (interest-bearing private debt) must be loaned into existence, and banks lend to those with collateral, those at the top. In a sovereign money system, the new money (non-interest-bearing public debt) could be spent by the Treasury into the economy at the bottom to finance public goods and real production and employment (for an explanation of sovereign money, see Positive Money). Giving private banks the right to create money, as does our fractional reserve system (that no one ever voted for), is a giant subsidy to the private banking sector. Incidentally, the Fed is owned by these member banks who profit from excessive money creation, even though it is supposed to act independently in the public interest.

Herman Daly is CASSE Chief Economist, Professor Emeritus (University of Maryland), and past World Bank senior economist.

Herman Daly is CASSE Chief Economist, Professor Emeritus (University of Maryland), and past World Bank senior economist.

Wow. So the price of Property goes up, but they’re careful to limit the rate of rise in the cost of Living?!? I had no idea that there’s an inflation differential, but it totally makes sense. So, since inflation is being suppressed, it seems obvious that the reckoning is going to involve severe inflation.

Can I ask you how transaction costs fit into the steady state solution?

I’ve been thinking about Vilfredo Pareto’s observation that there’s two ways of acquiring wealth: to produce it or co-opt wealth that’s produced by others; and it seems like there’s an important branch of economics that’s been entirely neglected. I call it the Dark Arts Of Appropriation: how does one go about co-opting the wealth of others?

Obviously, land rent is huge. Not only does it deliver public wealth to the landowners, but it creates parasitic industries that support the land rent scam. Finance is clearly another culprit. The framework that seems to fit for all of the cheating is an exaggeration of transaction costs: unproductive agents seek excessive compensation for whatever valuable services they do provide. I would certainly argue that transaction services are critically important for society, but it seems that each institution has an incentive to inflate its own transaction costs with the monopoly power that they have access to: military, healthcare, finance, etc.

Is there anything about the SS solutions that would serve to structurally dampen the rise of transaction costs? Georgism would take a big bite out of the parasitic load, but what about the industries like finance and healthcare? Is that something that could be tempered with structural economic solutions, or would it have to be through some sort of democratic accountability?

Thanks, Andy

Indeed, I have been bugged by this very thing for several years and tried pointing it out to our local Member of Parliament. He sort of thought about it, I guess. Anyway, next time I came across him he said to me (and everyone near me): “Oh, Brian doesn’t like Growth” and then he quickly moved on.

Ah well. I’m glad I’m not an economist. If I were, I might feel some professional responsibility for such nonsense.

Governments oppress cosmic powered biology manifest as human. So what comes next?

Thank you, Herman, for this important article on the failings of official estimates of The Inflation Rate.

About two decades ago, I argued in my Master’s thesis that the government’s calculations of ‘The Inflation Rate’ hid some very important information re: inflation that all economists should really care about and want to measure: the variance of inflation rates across different income groups.

It is indeed possible for one income group to experience robust, accelerating inflation at the same time that another income group is experiencing dis-inflation, or even deflation. Even a cursory review of the historical data shows that this is precisely what has happened in America since Congress began in the 1980’s to throw free money at all rich people through successive reductions in their income tax obligations.

This very important economic reality has been hidden from view by government estimates of “the overall rate of inflation” which intentionally exclude changes in asset prices from their calculations. Changes in assets prices are treated as a special sort of economic phenomenon that has nothing at all to do with inflation, but is an important indicator of the health of the entire economy.

Whether this misrepresentation of inflation is intentional, as you and I both suspect, or simply the result of the mind-blowing ignorance of generations of theoretical economists, it is an analytical failure that can be rather easily corrected by compiling and publishing a spectrum of inflation rates which spans the entire hierarchy if disposable incomes.

This would be derived, of course, through the identification of “market baskets” which rationally apply to the members of particular income brackets. How do they spend most/all of their disposable income?

Money that rich people spend on financial and real assets would have to be included in market baskets of rich people, properly weighted to account for the percentage of their income that they apply to those purchases.

The result would be a spectrum of inflation rates which would provide policy-makers with some important information re: the consequences of their fiscal policy options.

One revelation: the asset bubbles we’ve seen over the past four decades are actually entirely attributable to the income tax cuts that rich people have been given over that period. If you want to prevent asset bubbles, or at least moderate them, then stop cutting the taxes of rich people, or maybe even raise them once prices in asset markets start to accelerate.

Publishing a spectrum of inflation rates would force economists and policy-makers to ask: why should we, or shouldn’t we, recommend a fiscal policy that will grant one income group a higher rate of inflation than other groups? What real economy consequences can we point to that would justify such a policy?

Ultimately, I suppose, we have Irving Fisher and his references to “The Price Level” for popularizing the specious notion that Inflation is a mysterious effect within the economy which spreads out evenly over the entire economy like a mist. Nothing of the sort is remotely true.

Note to government economists at the BLS: publishing an “average” inflation rate which hides the variance of inflation rates across income groups is an analytical failure—and intellectual sin—that economists as a clan should feel profoundly embarrassed about…

Since reading H.Daly in the 70’s, I have written and published (with Scribners in 1975) four books portraying who we are as human beings, what a steady state might look like, how it could be threatened, and how we can rise above our sense of failure to find meaning and resolve to fix that which is obviously broken. The fourth book in the Archives of Varok is coming soon–dealing with the

silent topic of overpopulation. It’s not scifi. I’m a realist about space travel but grew up with the Oz books–hence my “aliens” are realistically close and obnoxious in their preaching (but a handy literary tool to bounce real ideas off open minds). You’re invited to http://archivesofvarok.com and welcome to review and consider them for mature readers (7th grade to 79). I’m on Twitter and Facebook.