Book Review: Economics Unmasked: From Power and Greed to Compassion and the Common Good by Phillip B. Smith and Manfred Max-Neef

by Herman Daly

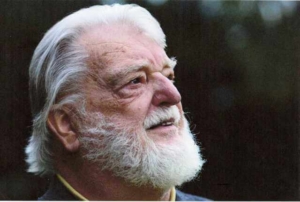

Manfred Max-Neef is a Chilean-German economist noted for his pioneering work in human scale development and his threshold hypothesis on the relation of welfare to GDP, as well as other contributions, for which he received the Right Livelihood Award in 1983. Phillip B. Smith (deceased, 2005) was an American–Dutch physicist with a devotion to social justice that led to an interest in economics. Smith died before this collaborative work was completed, so it fell to Max-Neef to finish it, respecting what Smith had done. Although this results in differences in style and approach between chapters, Max-Neef informs us that they both read and approved each other’s contributions, so it is a true collaboration. These differences between the physical and social scientists are complementary rather than contradictory.

As clear from the title, the book argues that modern neoclassical economics is a mask for power and greed, a construct designed to justify the status quo. Its claim to serve the common good is specious, and its claim to scientific status is fraudulent. The latter is sought mainly by excessive mathematical formalism to the neglect of concrete facts and real values. The mathematical formalism is in imitation of nineteenth-century physics (economics viewed as the mechanics of utility and self-interest) but without any empirical basis remotely comparable to physics. Pareto is identified as a villain, and to a lesser extent, Jevons.

The hallmark of real science is a basic consensus about fundamentals. There is no real consensus in economics, so how can it claim to be a mature science? Easy: By forcing a false “consensus” through the simple expedient of declaring heterodox views to be “not really economics,” eliminating history of economic thought from the curriculum, instigating a pseudo-Nobel Prize in Economics, and attaining a monopoly on faculty positions in economics departments at elite universities. Such a top-down imposed consensus is the opposite of the true bottom-up consensus that results when independent minds all bow before the power of the same truth. “Mathematics was simply built into the laws that describe the behavior of the atomic nucleus. You didn’t have to impose it on the nucleus” (p.67). The same cannot be said of people, even atomistic homo economicus.

The authors give due attention to the history of economic thought, drawing most positively on Sismondi (for statements of value and purpose), Karl Polanyi (for his treatment of labor, nature, and money as non-commodities that escape the logic of markets), and Frederick Soddy (for his thermodynamics-based analysis of money, wealth, debt, and the impossibility of continuing exponential growth of the economy). Negative references are reserved mainly for Friedrich von Hayek and Milton Friedman, with a mixed review for Amartya Sen. While I understand their antipathy to Hayek, I found their case against him less than totally convincing. More convincing and fruitful is their building on the neglected work of Sismondi, Polanyi, and Soddy. That effort cries out to be continued by others.

Neoclassical economics is a mask for power and greed, argues Manfred Max-Neef. (Image: CC0, Credit: ZIPPASGO).

Their criticisms of globalization, free trade, and free capital mobility are well-founded. Economists must remember that the first rule of efficiency is to count all costs, not to specialize according to comparative advantage, especially if that “advantage” is based on a standards-lowering competition to externalize environmental and social costs. Indeed comparative advantage is irrelevant in a world of international capital mobility that gives priority to absolute advantage. While specialization according to absolute advantage gives gains from trade, they need not be mutually shared as in the comparative advantage model.

Chapter Ten provides a summary of the basics of ecological economics as “the humane economy for the 21st Century,” as well as a review of Max-Neef’s insightful matrix of needs and satisfiers.

Of particular interest is Chapter Eleven on “the United States as an underdeveloping nation”—the process of development in reverse, or retrogression in the U.S. is chronicled in terms of unemployment, wage stagnation, increase in inequality, dependence on food stamps, bankruptcy, foreclosure, health care costs, incarceration, etc. Not happy reading, but a necessary reminder that gains from development are not permanent—they can be squandered by a corrupt elite employing a self-serving economic model to fool a distracted populace.

As a teacher of economics, I was especially glad to read Chapter 12 on “the non-toxic teaching of economics.” I concur with the authors’ view that the teaching of economics today is a scandal. Reference has already been made to the dropping of history of economic thought from the curriculum—why study the errors of the past now that we know the truth? That is an arrogant attitude. And we certainly do not want any philosophical or empirical questioning of the canonical assumptions upon which the whole superstructure of mathematical deduction teeters. Growth must not be questioned because it is by definition the solution to all problems—even those that it causes.

Academia, such as Yale Univesity, has limited the range of economic studies where present-day economic students study growth economic as opposed to multiple avenues of economics. (Image: CC0, Credit: 12019).

As late as the 1960s, economics students could study approaches other than the neoclassical—there were the remaining classical economists, institutional economists, the Marxians, the Keynesians, the Austrian School, labor economics, Fabian Socialists, Market Socialists, Distributists, etc. Now there is a cartel of elite, expensive universities, “the Big Eight” as the authors call them (California, Harvard, Princeton, Columbia, Stanford, Chicago, Yale, and MIT) to which we could add Cambridge, Oxford, and a few others. They all teach the same growth-oriented, globalizing economics. The IMF and the World Bank hire economists from many countries and pride themselves on their diversity. But the diversity of nationality and color masks homogeneity of viewpoint since 90 percent of these economists graduated from the Big Eight, and are comfortable with both their position and their economic views. One wag succinctly described a frequent career path as “MIT-PhD-IMF-BMW.”

Further evidence of the corruption of economics arrives daily. The documentary film Inside Job exposed the complicity of some Big Eight faculty in the financial debacle of 2008. I recently read that the Florida State University economics department has accepted a grant from the right-wing Koch Brothers to hire two prestigious economists with acceptable views, no doubt products of the Big Eight, whose presence on the faculty will raise FSU a step on the academic ladder. All corruption in academia cannot be blamed on economics departments, but the toxicity level there is high, and Max-Neef and Smith are right to accuse. One good way for honest economics professors to fight back is to recommend this book to their students!

The book ends with a hopeful review of some concrete, real world, bottom-up, human-scale development initiatives. The World Bank and the IMF are necessarily absent from this final chapter’s discussion of moving from village to global order. Might it be that after the globally integrated collapse we will move to village reconstruction, and then to a global federation of separate national economies under the principle of subsidiarity?

Herman Daly is CASSE Chief Economist, Professor Emeritus (University of Maryland), and past World Bank senior economist.

Herman Daly is CASSE Chief Economist, Professor Emeritus (University of Maryland), and past World Bank senior economist.

2018 Tony Webster

2018 Tony Webster

Definitely then a pending purchase. Amazon has this for just under $15, paperback, excluding postage and handling.

Looks quite interesting. I wonder if the authors qualify as ‘good economists’ according to Bastiat’s definition:

“Between a good and a bad economist this constitutes the whole difference – the one takes account of the visible effect; the other takes account both of the effects which are seen, and also of those which it is necessary to foresee. Now this difference is enormous, for it almost always happens that when the immediate consequence is favorable, the ultimate consequences are fatal, and the converse.”

Of course, Monetarists and Keynesians both fail this test. The Austrians insist they pass it, and for my money, they do a better job than the mainstreamers, but they have the same blindness when it comes to disregarding the limits to growth imposed by a finite and interconnected living world.

I very much like your vision of an economic federation based on subsidiarity! Although I would prefer it be based on regions – organically occurring fragments of present nations. It would be an interesting project to sketch out how that might take shape. I am concerned that, continuing to live in the thrall of cultural myths, humanity will learn all the wrong lessons from the collapse and continue to view a top down sociopolitical structure as something to emulate.

Thanks for an intelligent and thoughtful review of what looks to be an intelligent and thoughtful book. :)

– Oz

writing from Ireland, I have to say I agree with Oz. I am much taken by the principles of MMT and the concept of a Guaranteed Job Scheme but I too had observed a lack of interest from the monetarists regarding the limits to growth. We are currently organising a major economic conference which will confront traditional economists and commentators with other ideas such as how rising energy prices will dampen any trust in global growth to solve the debt crisis and other options such as a complementary currency. You could read more about these home grown Irish proposals on feasta.org and/or smarttaxes.org