Steady State Transportation: Closing the Door on the Dirty Oil Era

by Brent Blackwelder

If human civilization is to make the move to a steady state economy that provides prosperity without growth, it must meet people’s basic mobility needs without reliance on fossil fuels. The U.S. requires a revolutionary transformation of its transportation systems, and recent experience with the downsides of oil provides a potent political push to overcome inertia.

Image Credit: Neoporcupine

In the United States, the transportation sector consumes about 60% of the oil and is responsible for about one-third of greenhouse gas emissions. We use more gasoline than the next 20 nations combined. America has 2.6 million miles of paved roads with 3 cars for every 4 people in the country, and 88% of people get to work via automobile.

Concerns about global climate destabilization and dramatic water pollution have put the issue of oil usage front and center. The world has focused on the tragedy of the gigantic BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico that began on April 20. But numerous other spills, leakages, and pipeline breaks have occurred since April. For example, the Enbridge pipeline ruptured the last week in July and spilled over one million gallons of oil into the Kalamazoo River in Michigan. As with BP, this recent spill was not a unique mishap but rather one in a long series of accidents and violations in Enbridge’s history.

Over the past decade, there have been over 1,600 accidents with oil pipelines in the U.S. The year 2010 is not extraordinary for its mishaps, but merely business as usual in the oil industry. It is naïve to think that Congress or state legislative bodies can tighten regulatory and enforcement regimes to solve the problem. Friends of the Earth and other environmental groups have tried this route, but oil is inherently dirty. In addition, the oil industry is politically powerful, and well-intentioned protections often fail to curtail the massive amounts of leakage and spillage in the U.S. and around the word.

To achieve optimal economic scale and a true balance with nature in a steady state economy (i.e., healthy ecosystems and a healthy economy), boldness is required, and the transportation sector is a good place to start. Ending the use of oil to power vehicles, from planes to trains to automobiles, is a must. But the power of the highway lobby and the momentum of the global jet-setting economy’s demands make this objective appear improbable.

Some encouraging signs of change, however, provide the basis for making big demands on Congress, state legislatures, and the executive branch. For example, public support for spending the preponderance of federal transportation dollars on road construction (instead of public transportation) may be cracking significantly. On July 25th the Chicago Tribune reported that for the first time, both suburban and urban citizens in the Chicago metro area think that more money ought to be spent on transit than on highways.

Another promising sign is the growth in U.S. transit ridership. Since 1996 transit ridership has increased by an average of 2.6% annually, including a 3.3% increase in 2009.

Recent economic analyses highlight the costliness of oil and automobile usage, and evidence from these analyses can drive big shifts in policy. For instance, the U.K. Department of Transport has found that for each British pound spent to reduce car usage, there are £10 of benefits in the economy from fuel savings, reduced congestion costs, and lower pollution levels.

But America lags far behind other nations in rethinking transportation systems – a quick comparison of Atlanta to Amsterdam demonstrates the gap. In Atlanta 95% of residents commute to work by car. In Amsterdam 40% commute by car, 35% bike or walk, and 25% go by transit. The series of oil spills in the U.S. this year should energize efforts in city after city to revamp transportation and breathe new life into automobile alternatives.

My brother Brion Blackwelder, who is a law professor at Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, suggests several standards that a modern 21st century transportation system should meet:

1. Zero tolerance for death and injury;

2. Congestion as a rarity rather than a daily occurrence;

3. Small footprint in terms of land use, energy use, air and water pollution, and wildlife impacts;

4. Provision of services for the young, the old, the disabled, and the poor.

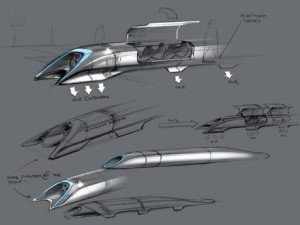

Not surprisingly, the United States flunks the test of meeting these standards. Take, for example, the first. Highway accidents each year in the U.S. claim the lives of about 40,000 people, and several hundred thousand more are seriously injured. Contrast this tragic record with Japan’s bullet trains. The speedy 322-mile route from Tokyo to Osaka, completed in 1964, has not had a single passenger fatality. Today 1,360 miles of high-speed rail link all of Japan’s cities.

Not surprisingly, the United States flunks the test of meeting these standards. Take, for example, the first. Highway accidents each year in the U.S. claim the lives of about 40,000 people, and several hundred thousand more are seriously injured. Contrast this tragic record with Japan’s bullet trains. The speedy 322-mile route from Tokyo to Osaka, completed in 1964, has not had a single passenger fatality. Today 1,360 miles of high-speed rail link all of Japan’s cities.

One way to confront the challenge posed by these standards would be to shift to mostly electric vehicles. Cars and trains could be run on electricity generated by wind, solar, and other renewable sources. For part of the 20th century, the Milwaukee Railroad operated 650 miles of electric rail over five Pacific Northwest mountain ranges on its Chicago to Seattle route.

It may come as a surprise that 100 years ago Henry Ford and Thomas Edison were so dissatisfied with the internal combustion engine that they were developing and selling all-electric cars from 1910 to 1914, when a mysterious fire burned almost all of Edison’s laboratories in December of 1914.

Now is the time to rekindle that vision, capitalize on the public’s awareness of the dirty consequences that consistently accompany our oil usage, reinforce the growing sentiment to invest in public transportation, and begin serious debate on a sustainable transportation system.

I enjoyed reading your article about moving on past petroleum. For the past several years, the sustainability community in the Pacific Northwest has been actively exploring ways to lower everyone’s energy footprint. One innovative idea is revitalizing the use of sailboats for transport and trade. The cooperative that I am involved with in Seattle, Salish Sea Trading Cooperative, has started a CSA delivery service and we are exploring other items for trade. We would love to talk with you! Thanks.

Wow, what a dud of an ending. You spend the entire piece cataloging the multiple catastrophe of our cars-first transportation system, then conclude with a call for electric cars!

Look, there is a question of basic physics here. Automobiles will still weigh at least a ton, 2,000 pounds, in even the happiest all-electric scenario. You suggest that use of a one-ton machine for daily commuting and errands is anything but a dire threat to the continuation of modern life? How do you imagine that?

Need we also mention that automobiles spend 95 percent of their lives sitting parked, unused?

Sheesh.

P.S. The Chevy Volt weighs almost 2 tons…

This article starts out good, then, inexplicably, concludes that replaceing millions of gas-powered mobile trash bins, with millions of EV;s is the solution to the evils of the ICE car…mmmmm. While there is nothing inherently wrong with EV;s as such, would argue against EV emergency, or utility vehicles for example? But replaceing millions of ICE cars with millions of EV’s will leave most of the inherent problems created by personal commuter cars un-resolved, sprawl, massive resources directed to maintaining highways etc.

Most people in the USA depend on private automobiles for most of their transportation. However, if we think of this method of transportation, based on private vehicles driven on public highways, as a transportation system, and start counting up the costs, it quickly becomes clear that we have the most expensive transportation system in the world. In addition to the direct monetary costs, which total somewhere around $1.5 Trillion each and every per year, there are additional costs from many thousands of deaths and injuries costs each year, huge environmental costs, and added military costs. However, due to the political gridlock in Washington, the chances that our government will make any significant changes in transportation policy anytime soon are slim to none. Most politicians are apparently afraid to even acknowledge the true scope of these costs. So what can we do without any government leadership?

In the absence of any government leadership, our only choice is to make individual changes. True, the net savings from one individual making a change, even a big change, will be negligible. But successful changes can be a model for other people to follow. And if enough of us make individual changes, the cumulative savings will be large. With the average annual cost for maintaining an automobile in the range of $6500 per year, there is plenty of incentive for an individual to make changes to reduce both their energy use and operating costs for transportation.

Before rushing out to buy a new electric car, we should consider the typical stages of change, as applied to transportation energy and cost savings. Typically a first stage would be to switch to a more efficient car, such as a Hybrid or all electric car. A typical second stage change would be to drive your car, or cars, less, by switching to a bicycle or public transportation whenever possible. The switch proposed by Brent Blackwelder, to an electrically driven public transportation system, would be an example of this second stage of change. A typical third stage change would be to change jobs, or move from the suburbs back to town, so that you don’t need to travel as much.

While many people will fixate on the initial costs, each of these changes can usually yield sufficient energy and cost savings to justify the change. For example, switching to a more efficient car can be very cost effective, if the fuel savings are more than enough to justify the initial cost for the more efficient car. And the most cost effective change might be to find a good used car that gets much better fuel mileage than your old one, rather than buying an expensive new hybrid. Likewise, driving less can be very cost effective, especially if a family finds that it can get by with one less car. And moving back to town might allow a person, or even a whole family to, give up all their cars, and rely on a car sharing service or a rental for occasional weekend trips.

And, of course, there is no law that requires that we make all three changes in sequence. For some people it will be feasible to take a shortcut and reap the benefits of all three stages of change in one fell swoop. For example, someone who now lives in the far suburbs and commutes sixty miles each work day in a car, might decide to pack up and move to an apartment four blocks from work, start walking to work, sell the minivan, and sign up for a car sharing service. Such an all-in-one change might reduce that person’s transportation energy use and costs by 90%, without any help or prodding by the government. And just as our current system has high external costs, a move back to town may have high external benefits, such as more leisure time, more attractive options for using that newfound leisure time, and more discretionary income to use for those activities.

So before calling our congressman to demand new high speed electric trains, we should consider what changes we can make by ourselves, and start preparing for those changes.

We have been advocates of Mass, Public, Urban and Alternative forms of transportation for many years. This is a crucial subject to the environment and our everyday ways of life. If you have a chance, please check out our site by visiting the following link: Transit-Forum