The Top Three Actions to Fix the Economy

by Rob Dietz

Fixing the economy will require more than tax code tweaks and stock market peaks. Anyone who’s been paying attention knows that we need big changes to the way we run things on this planet. Even a partial list of today’s social and environmental problems sounds grim:

- An unfathomable number of people (2.7 billion) live in poverty, scraping by on less than $2 per day.

- Our penchant for burning fossil fuels has increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere such that scientists are throwing around phrases like “runaway climate change.”

- National governments are drowning in debt, while the global financial system teeters on the verge of ruin.

- The health of forests, grasslands, marshes, oceans, and other wild places is declining, to the point that the planet is experiencing a species extinction crisis.

Result s like these arise because the global economy has grown too big for the broader systems that contain it. We have too many people consuming too much stuff. Sure, the engine of economic growth has driven technological advances and provided a dizzying array of consumable goods. But it’s hard to argue that these material benefits outweigh the costs of social breakdown and environmental upheaval.

s like these arise because the global economy has grown too big for the broader systems that contain it. We have too many people consuming too much stuff. Sure, the engine of economic growth has driven technological advances and provided a dizzying array of consumable goods. But it’s hard to argue that these material benefits outweigh the costs of social breakdown and environmental upheaval.

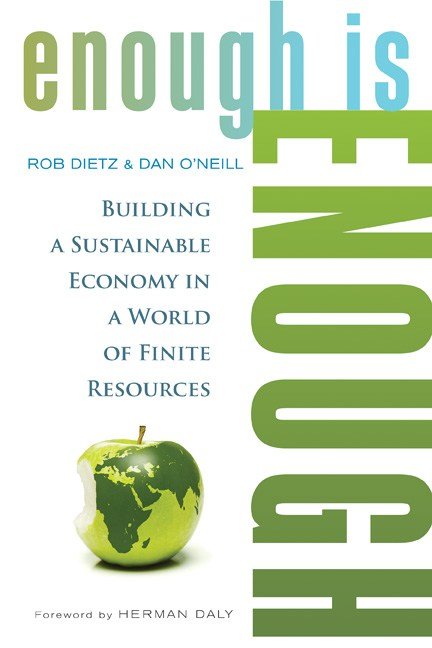

So we need a systemic change, but what are our options? We could try to increase the size of the planet, or try to find another one that’s habitable. But maybe it would be more prudent to focus on changing the economy. That means shrinking, and then stabilizing, the economy so that it can meet humanity’s needs while conserving and protecting the ecosystems that support life on Earth. The book I wrote with Dan O’Neill, Enough Is Enough, describes policies to do that, but as Peter Victor has noted:

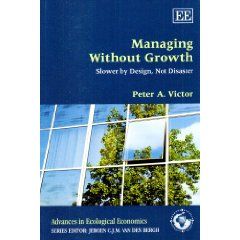

The dilemma for policy makers is that the scope of change required for managing without growth is so great that no democratically elected government could implement the requisite policies without the broad-based consent of the electorate. Even talking about them could make a politician unelectable.

Victor’s statement rings true. For example, in the last U.S. Presidential election, the candidates sparred with each other over who could grow the economy faster and create the most jobs. Suppose that instead of trying to “outgrow” his opponent, President Obama had run on a platform of stabilizing the economy. You can almost hear President Romney’s inaugural address about more oil pipelines, more highways, more consumption, more, more, more. But to the climatologists, conservation biologists, and ecological economists (and even the butchers, bakers, and candlestick makers) who are tracking the limits to growth, it is becoming increasingly clear that we need to make room for our leaders to discuss economic stabilization. It’s time for them to begin working on an economy that aims for enough instead of always chasing more.

From Victor’s quote, we can deduce the top three things we need to do to begin the transition to such an economy.

From Victor’s quote, we can deduce the top three things we need to do to begin the transition to such an economy.

1. Achieve widespread recognition that our planet is finite and that our economy has to fit within ecological limits. Politicians can’t talk about the limits to growth because most of the electorate remains unaware of the limits. Even with increasing attention paid to climate change and other developing crises, the conversation rarely turns to overconsumption in the economy. Schools are not teaching ecological economics, and people are too distracted by the routines of daily life to pay much attention. We need compelling stories and broad public education to get people discussing critical topics such as the relationship between environmental and social systems, humanity’s place within nature, and the benefits of a steady-state economy.

2. Provide a set of practical policies for achieving a steady-state economy. All citizens (even the politicians) need to understand what can replace the growth-obsessed policies in use today. As soon as people begin to get a feel for how a well-conceived set of steady-state policies can outperform the obsolete policies of endless growth, politicians will gain the broad-based support they need to overhaul the system. The heart of Enough Is Enough describes this set of policies, but even a quick glance at them confirms Victor’s point: the scope of change required is indeed great. That’s why we need more than just awareness of the problem and a set of policy proposals.

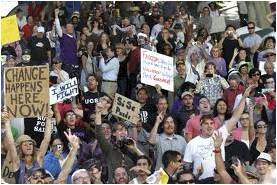

3. Cultivate the will to act. Economic changes won’t materialize on their own. People have to want out of the current system, and they have to demand the transition to a new one. Without such pressure, entrenched elites (in both politics and business) have no incentive to overturn the status quo. There’s an awful lot of networking and organizing to be done.

With these three actions, we can get the economy we want and the planet needs. The unelectable politicians will be the ones who cling to the wishful thinking of perpetual growth. It’s time to take a stand, to put aside the destructive mania for more, and let our lawmakers know that enough really is enough.

Rob Dietz brings a fresh perspective to the discussion of economics and environmental sustainability. His diverse background in economics, environmental science and engineering, and conservation biology (plus his work in the public, private, and nonprofit sectors) has given him an unusual ability to connect the dots when it comes to the topic of sustainability. Rob is the author, with Dan O’Neill, of Enough Is Enough: Building a Sustainable Economy in a World of Finite Resources.

Rob Dietz brings a fresh perspective to the discussion of economics and environmental sustainability. His diverse background in economics, environmental science and engineering, and conservation biology (plus his work in the public, private, and nonprofit sectors) has given him an unusual ability to connect the dots when it comes to the topic of sustainability. Rob is the author, with Dan O’Neill, of Enough Is Enough: Building a Sustainable Economy in a World of Finite Resources.

It’s essential that we understand the nature of a wonderful means in our economy: money.

If we would understand the true nature of money we would more easily apply the limitations that should be respected in the economic system in order to reach a stable system.

see also: http://gearedeconomy.blogspot.nl/2013/01/geared-economy.html

“It’s essential that we understand the nature of a wonderful means in our economy: money.”

I would totally agree to that, but I would include an understanding of debts.

If I had the power to change just one law in current industrial societies to make the transition to a sustainable society possible, I would change the way we treat the legislation of debts.

It also sounds like an argument that could put forward by the advocates of the “small state”, but of course never will be.

The change would be that the state, meaning the legislature and executive branch, would not in any way enforce a debtor to pay back a loan to a creditor. It would be a contract between the two parties, and due repayment of debts would be the responsibility of both sides. Of cours a creditor would have the right to remove the debtors credit worthiness if the debtor could not fulfill his obligations, but that would be it.

If a loan contract would be free of the structural violence the state can issue forth in favor of the creditor our system would be stood on its head. Loans would no longer be the means for ruin and slavery.

The satisfaction of increasing debts is the reason why growth capitalism exists. Markets must grow because the absurd ammount of wealth the very few have accumulated grow exponentially, and with them loans and interests.

Most credit gven worldwide today is given as a means to ruthlessly suppress and to exploit. The reason for the unequality in this world is this law for the enforcement of repayment of loans.

By using debts we are able to press indebted nations into giving up their ressources for our gluttony. The global empire of multinational corporations, based in the USA or Europe, is based on a harsh rule of debt enforcement. It is the means to keep the unwilling in line.

The laws concerning debts stand in stark contrast to the often invoked religious believes of christianity by the political right, who are often identical with the “small state” advocates in the conservative right. The usurer was shunned in all great religions in preindustrial times, but not by conservatives. The neoliberal economist is the high priest of a new religion, ant this one is not forgiving.

The “Lords prayer” invokes the right for forgiveness of debts, the societies ostensibly built on these believes do not.

any normal, sane. thinking person recognises that there are limits to growth, and that growth is going to come to an end, probably in a very unpleasant manner, and soon

but

please not ‘my’ growth, at least not yet.

While Peter Victor’s words are beyond dispute, I fear that they are an amalgam of wishpolitics wisheconomics and wish-science

we will not accept that growth is finished until growth is physically, and I fear brutally stopped in its tracks by forces stronger than ourselves.

I cannot pay off my 25 year mortgage in a no-growth economy, because my job will downsize to a level where I cannot earn enough to do so. That debt will not cease to exist just because of some fanciful idea of a no growth economy, if I cannot pay it, then I will lose my home. It really is that simple, If the state has entered a no-growth phase, that means I will probably starve, because community care depends entirely on the excess production of the community itself. Diminished output (no growth) means that there is no excess to feed and house the needy. That’s just one aspect of it, I could cite lots more.

So please, when waffling on about ‘no growth’ try to think it through, and imagine the full horror of what it means. Growth is going to stop, but we will not enter into a universal utopia because of it, quite the opposite.

In my view item number 2, laying out a practical set of social/economic policies to achieve a steady state economy, is the real key. A fairly widespread perception that we need to live within ecological limits already exists. Giant earth raping corporations regularly publish claims about the ‘greenness’ of their corporate policy. Of course one can argue that these claims are purely Machiavellian public relations BS. However, in my view they are (for the most part) examples of cognitive dissonance, and the stated belief in the importance of ‘greenness’ is real. As for item number 3, the will to action requires a plan addressing the substantive issues to be resolved before it can find effective expression.

In my opinion there are three central principles which any practical set of policies designed to bring about an economic system with long term stability must include:

1. The unbounded competitive accumulation of consumption right must be replaced by bounded accumulation of consumption rights.

2. Private, for profit credit markets must be replaced by not for profit, community credit markets.

3. Retirement security should be based on the building up of social credit by supporting the elderly rather than by monetary savings.

Obviously anyone who believes in limits to growth is on board with principle number 1, but support for principles 2 and 3 is much harder to find. Many people seem to believe that private credit markets and money as a long term store of private value can be reformed and regulated into a sustainable form, but I must respectfully disagree. Money as practical medium for of making economic exchanges and money as an information system for directing economic effort is still potentially useful in an economy with long term ecological stability. However, money as a long term store of value is death to any attempt to live within ecological limits.

I wonder if the focus should be on the concept of policy makers the electorate. There has to be a way of removing the gap and getting the whole community involved. We need educators to inform the community so that we can have informed decision making, not just managing perceptions of voters. Change cannot be imposed from above without the community being involved. Responsible leaders would see their role as informers.

I’m sorry NoMore, but you really need to change your pseudonym to NoIdea. You have completely misread the Peter Victor quote which, apart from pointing out how difficult it will be to transition to a ‘no-growth’ or steady-state economy, is more about hope than wishing.

While, like you, I’m not overly optimistic about a steady-state economy emerging though human design (more like through natural disaster), you do not understand the most basic aspects of steady-state economics.

Firstly, in a steady-state economy where the emphasis is on the production of better goods instead of more goods, you would be able to pay off your mortgage. Better goods command higher prices relative to low quality substitutes and therefore enable higher profits and higher nominal wages to be earned from the production of the same quantity of goods. Although the higher prices would cancel out the rise in nominal wages, real wages would remain unchanged and enable workers to afford the same quantity of the now better quality goods (i.e., consumption-related benefits would increase). Meanwhile, your mortgage repayments wouldn’t rise in nominal terms but instead fall in real terms. So it would be easier for you to pay off your house. Indeed, so much so, you may be able to reduce the number of hours you work each week, thus giving you more leisure time/time with your family, etc., and helping to reduce unemployment through job-sharing. The decreased production combined with some efficiency improvements would also reduce the quantity of resources used and pollution generated, so you would also be able to enjoy your increased leisure time in a cleaner, less scarred environment. Sounds good, doesn’t it?

Secondly, diminished output does not mean a lack of goods and services to feed and house the needy. There already is a gross excess of goods and services. It’s just that the excess is being syphoned off to the small percentage of absurdly affluent people – people, by the way, whose money income far exceeds their true contribution to wealth accumulation (economic rents), much of which could be taxed away without any reduction in their motivation to work (if you know anything about economic rents). True, these people could emigrate, but that may not be a bad thing. No-one is irreplaceable and all they would be taking with them is their money. They can’t take the real, useful stuff that their money (spending power) would otherwise allow them to claim, and would thus free up some of the real stuff for the needy to claim. Some of this unclaimed real stuff could also be acquired by governments (currency-issuing central governments have no spending constraint, despite the nonsense and unfounded fear being circulated about central-government deficits – see Billy Blog) to provide the infrastructure needed to have in place a clean, green, renewable energy-dependent, and low-carbon economy (including access for all to adequate health and education facilities and services).

So, please, before waffling on about ‘no-growth’, first learn some basics about steady-state economics. Start by reading this blog site more often with the recognition that the people who contribute towards it are no fools. Better still, read some of their work. Then you might understand that a well-designed steady-state economy is nothing to be feared but something to be embraced.