Fitting the Name to the Named

by Herman Daly

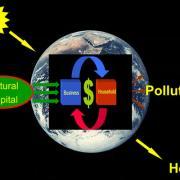

There may well be a better name than “steady state economy,” (SSE) but both the classical economists (especially John Stuart Mill) and the past few decades of discussion, not to mention CASSE’s good work, have given considerable currency to “steady state economy” both as concept and name. Also, both the name and concept of a “steady state” are independently familiar to demographers, population biologists, and physicists. The classical economists used the term “stationary state” but meant by it exactly what we mean by steady state economy—briefly, a constant population and stock of physical wealth. We have added the condition that these stocks should be maintained constant by a low rate entropic throughput, one that is well within the regenerative and assimilative capacities of the ecosystem. Any new name for this idea should be sufficiently better to compensate for losing the advantages of historical continuity and interdisciplinary familiarity. Similarly, SSE conveys the recognition of biophysical constraints and the intention to live within them economically—which is exactly why it can’t help evoking some initial negative reaction in a growth-dominated world. There is an honesty and forthright clarity about the term “steady state economy” that should not be sacrificed to the short-term political appeal of vagueness.

A confusion arises with neoclassical growth economists’ use of the term “steady state growth” to refer to the case where labor and capital grow at the same rate, thus maintaining a constant labor to capital ratio, even though both absolute magnitudes are growing. This should have been called “proportional growth,” or perhaps “steady growth.” The term “steady state growth” is inept because growth is a process, not a state, not even a state of dynamic equilibrium.

The best method to achieve longevity is to embrace sustainability and a steady state economy. (Image: CC0, Credit: WikiImages).

Having made my terminological preference clear, I should add that there is nothing wrong with other people using various preferred synonyms, as long as we all mean basically the same thing. Steady state, stationary state, dynamic equilibrium, microdynamic-macrostatic economy, development without growth, degrowth, post-growth economy, economy of permanence, “new” economy, and “mature” economy. These are all in use already, including by me at times. I have learned that English usage evolves quite independently of me, although like others I keep trying to “improve” it for both clarity and rhetorical advantage. If some other term catches on and becomes dominant then so be it, as long as it denotes the reality we agree on. Let a thousand synonyms bloom and linguistic natural selection will go to work. Likewise, it is good to remind sister organizations that their favorite term, when actually defined, is usually a close synonym to SSE. If it is not then we have a difference of substance rather than of terminology.

Out of France now comes the “degrowth” (decroissance) movement. This arises from the recognition that the present scale of the economy is too large to be maintained in a steady state—its required throughput exceeds the regenerative and assimilative capacities of the ecosystem of which it is a part. This is almost certainly true. Nevertheless “degrowth,” just like growth, is a temporary process for reaching an optimal or at least sustainable scale that we then should strive to maintain in a steady state.

Growth and Degrowth

Some say it is senseless to advocate a steady state unless we first have attained, or can at least specify, the optimal level at which to remain stationary. On the contrary, it is useless to know the optimum unless we first know how to live in a steady state. Otherwise, knowing the optimum level will just allow us to wave goodbye to it as we grow beyond it—or as we “degrow” below it. Optimal level is one thing; optimal growth rate is something else. Once we have reached the optimal level then the optimal growth rate is zero; if we are below that level the temporary optimal growth rate is at least known to be positive; if we are above the optimal level we at least know that the temporary growth rate should be negative. But the first order of business is to recognize the long run necessity of the steady state and to stop positive growth. Once we have done that, then we can worry about how to “degrow” to a more sustainable level and how fast.

There is really no conflict between the SSE and “degrowth” since no one advocates negative growth as a permanent process, and no one advocates trying to maintain a steady state at the unsustainable present scale of population and consumption. However, many people do advocate continuing positive growth beyond the present excessive scale, and they are the ones in control and who need to be confronted by a united opposition!

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen recognized the limits of living in a finite universe. (Image: CC0, Credit: kamiel79).

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, adopted by the “degrowth” movement as its posthumous founder, indeed recognized that the very long-run growth rate must be negative given the entropy law and the final dissolution of the universe. But he did not advocate speeding up that cosmic result by negative growth as an economic policy, nor for that matter did he in the least advocate a steady-state economy! In fact, he speculated that the destiny of mankind might be to have a short, fiery, and exciting life rather than a long and uneventful one. He did, however, tentatively suggest a “minimal bio-economic program” that would surely reduce growth.[1] In general, he was interested in what is possible more than what is desirable. The question—given the limits of the possible, what is the most desirable policy for mankind?—was not his main focus, although he did not entirely ignore it. The closest he came to explicitly dealing with that question was in the following footnote: Is it not true that mankind’s problem is to economize S (a stock) for as large an amount of life as possible, which implies to minimize sj (a flow) for some “good life”?[2]

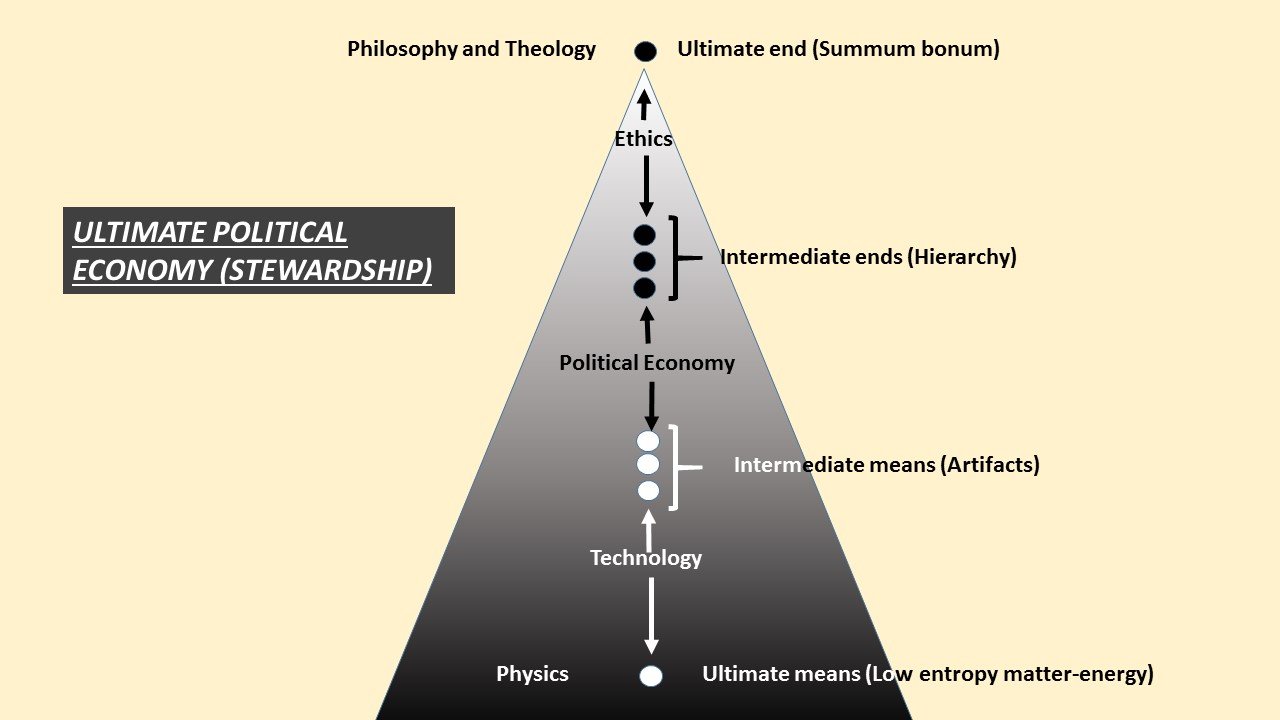

In other words, should we not strive to maximize cumulative lives ever to be lived over time by depleting S (terrestrial low-entropy stocks) at an annual rate sj that is low, but sufficient for a “good life?” There is no point in maximizing years lived in misery, so the qualification “for a good life” is important. I have always thought that Georgescu-Roegen should have put that question in bold in the text rather than hiding it in a footnote. True enough, eventually S will be gone and mankind will revert to what he called “a berry-picking economy” until the sun burns out, if not driven to extinction sooner by some other event. But in the meantime, striving for a steady state at a resource use rate sufficient for a good (but not luxurious) life seems to be a worthy goal, a goal of maximizing the cumulative life satisfaction possible under limited total resource constraints. This puts at the very center of economics the questions:

- How much resource use per capita is sufficient for a good life?

- How do we ensure that everyone gets that amount?

- How large a population can be supported at that standard of consumption without sacrificing carrying capacity and future life?

Needless to say, these questions have not been central to modern economics—indeed, not even peripheral!

Georgescu-Roegen did not like the idea of “sustainability” any more than that of a steady state economy because he interpreted both to mean “ecological salvation” or perpetual life for our species on earth—which of course flies in the teeth of the entropy law. And he was right about that. So sustainability should be understood as longevity, not eternal species-life in the sense of perpetuity. Clear scientific thinking about “forever” seems, interestingly, to lead to the religious model of death and resurrection, new creation, and not a perpetual continuation of this creation. Perpetuity in this world is just a glorified perpetual motion machine! To think about forever we must cross from science into theology. But longevity (a long and good life for both individual and species), even if it falls short of forever, or “ecological salvation,” is still a worthy goal both for scientists and theologians, not to mention economists. A steady state economy is arguably the best strategy for achieving longevity—regardless of what we call it.

Footnotes

[1] Georgescu-Roegen, N. 1993. “Energy and Economic Myths.”Valuing the Earth. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. See pages 103-4.

[2] Georgescu-Roegen, “Energy and Economic Myths”, page 107, footnote 11.

Herman Daly is CASSE’s Chief Economist, Professor Emeritus (University of Maryland), and past World Bank senior economist.

Herman Daly is CASSE’s Chief Economist, Professor Emeritus (University of Maryland), and past World Bank senior economist.

Perhaps “fitting the Name” is a game we should play with more “fitting” names for “growth” “wealth” and “development” among many terms that fail to measure the degradations that are acquired in direct and indirect proportion to what has become purely “monetarized” profit and relatively sub-population gains.

The only reality for a “sustained” economy is class structured zero sum progression and aggression. How can one possibly envision a steady state economy when the existing economy drives an unsteady political state of social inequality locally, regionally, nationally and internationally levels of both scale and scope.

Perhaps we should be discussing quality and not quantity of economic measures. Perhaps we need to make decisions about reciprocity and inclusiveness instead of competitive exclusion and the directives provided by a billion “invisible” hands fighting a regressive survival strategy to sustain “self” interest over orchestrated public choice parity.

On the theoretical side, there is a great deal of distinction to made in the names we employ. Certainly entropic equilibrium is distinct from the complexity of self organizing coordination that employs open system homeostasis.

A brief review of this type of distinction can be found here:

http://epress.anu.edu.au/info_systems/mobile_devices/ch11s03.html

a compliment to Herman Daly’s article with a spectrum of links for further research and study can be found here:

1) a prominent leading author (see his “on-line” books at bottom of the page):

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lester_R._Brown

(2)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brundtland_Commission

(3) SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: (with more than a half page of leading links to explore)

main article:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sustainable_development

The field of sustainable development can be conceptually broken into three constituent parts:

environmental sustainability,

economic sustainability and

sociopolitical sustainability.

I agree with Herman Daly that Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen did not believe in either sustainability or in the Steady-State Economy. Ultimately, as NGR saw things, there must be an ultimate period in which the rate of growth is irrrevocably negative, i.e., decline. As Herman Daly points out, this is consistent with Georgescu’s interpretation of the basic constraints of thermodynamics.

King Hubbert, too, envisioned a future in which resource constraints produce such “de-growth.”

What’s in a name? Beyond clarity of information and ideas, I think branding, marketing, and an overall communications strategy are directly embedded in any chosen name. I think we sell ourselves short, cutting the “united opposition” off at the knees, by not thinking about memes, about reaching people who are coming to this stuff from all sorts of different backgrounds and experiences and intelligences.

I’d like to be part of a “united opposition” that’s organizing to replace the growth economy in the spirit that Buckminster Fuller said “You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”

We need to build not an oppositional force, but a propositional force. We need to translate theories of steady state economics into living breathing community-level, town-level, county-level, and regional-level economies with real life jobs, food, production, education, healthcare, etc.

I’m so very appreciative of the theoretical underpinnings, and the need for improvements in our understanding of economics at this level. But we need to be designers, engineers, and architects of our future, and we need to both market these concepts and breathe life into them. The “new” economy starts now. I think it’s important to think about, as Bill McKibben and James Hansen both have, transcending their roles (journalist/author and scientist, respectively) to becoming the activists we needed. We need to get political — and clearly the Green Party is the only game in town when it comes to ecological economics. We need to get creative. And we need to hit the road and get our hands dirty. And have some fun doing it.

And that should all be reflected in a name!

Coming at this topic as someone with a lowly undergrad degree in economics from too long ago, and as an architect who also teaches and writes in areas related to sustainability and sustainable design, I’m very interested in some of the points expressed by Eli above. SSE (whatever its name) needs to make itself appealing not merely to its core, but to a much larger audience in order to overcome the knee-jerk public and political acceptance that “growth is good.”

SSE needs to portray a viable and enticing alternative structure (along with viable and enticing lifestyles), including a description of how we get from here to there. The Bucky quote is spot on. We have to change the model and convincingly show why it is a better path, both for the present and the future.

This is parallel, in ways, to my objection to the term “sustainability.” It is not affirmative enough. It implies merely existing and not moving forward, not flourishing.

I’m very interested in discussing methods of advancing these concepts and making them appealing to both a professional and lay audience.

My ruminations through my master´s program and thesis after years of activism have been toying with naming ideas like sustainable development constructivism, understood in terms of the UN CED 1992 Rio Summit approach of Agenda 21 and the Peoples´ Forum Declarations, social, environmental, and economic sustainable development. However, the recent development of the solidarity economics concept has lead me frequently to include the term “solidarity.”

The idea that sustainability seems constrained by long-term entropic processes is not a pragmatic focus, I think. In the short term, we are certainly confronted by the tremendous momentum of people acting from ideas acting in much shorter term dynamics. I like Gene Roddenberry´s Star Trek as a potential vision for the future, but certainly we have millions of years to figure that out if we can get passed the looming complications from short term trends.