The Populations Problem

By Herman Daly

The population problem should be considered from the point of view of all populations—populations of both humans and their artifacts (cars, houses, livestock, cell phones, etc.)—in short, populations of all “dissipative structures” engendered, bred, or built by humans. In other words, the populations of human bodies and of their extensions. Or in yet other words, the populations of all organs that support human life and the enjoyment thereof, both endosomatic (within the skin) and exosomatic (outside the skin) organs.

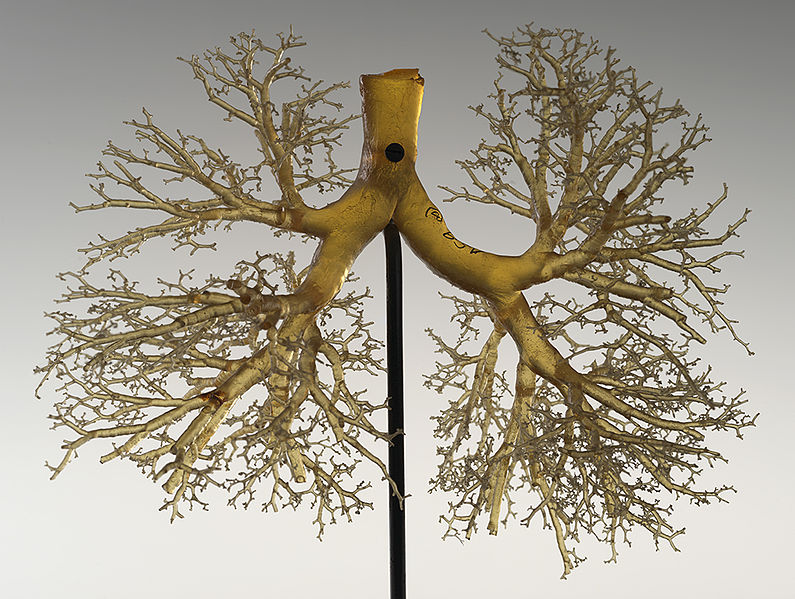

All of these organs are capital equipment that support our lives. The endosomatic equipment—heart, lungs, kidneys—support our lives quite directly. The exosomatic organs—farms, factories, electric grids, transportation networks—support our lives indirectly. One should also add “natural capital” (e.g., the hydrologic cycle, carbon cycle, etc.) which is exosomatic capital comprised of structures complementary to endosomatic organs, but not made by humans (forests, rivers, soil, and atmosphere).

The reason for pluralizing the “population problem” to the populations of all dissipative structures is two-fold. First, all these populations require a metabolic throughput from low-entropy resources extracted from the environment and eventually returned to the environment as high-entropy wastes, encountering both depletion and pollution limits. In a physical sense the final product of the economic activity of converting nature into ourselves and our stuff, and then using up or wearing out what we have made, is waste. Second, what keeps this from being an idiotic activity, grinding up the world into waste, is the fact that all these populations of dissipative structures have the common purpose of supporting the maintenance and enjoyment of life.

What good are endosomatic organs without the support of exosomatic natural capital? (Image CC BY-SA 2.0, Credit: Centre for Research Collections University of Edinburgh)

As A. J. Lotka pointed out, ownership of endosomatic organs is equally distributed, while the exosomatic organs are not. Ownership of the latter may be collective or individual, equally or unequally distributed. Control of these external organs may be democratic or dictatorial. Owning one’s own kidneys is not enough to support one’s life if one does not have access to water from rivers, lakes, or rain, either because of scarcity or monopoly ownership of the complementary exosomatic organ. Likewise, our lungs are of little value without the complementary natural capital of green plants and atmospheric stocks of oxygen. Therefore all life-supporting organs, including natural capital, form a unity. They have a common function, regardless of whether they are located within the boundary of human skin or outside that boundary. In addition to being united by a common purpose, they are also united by their role as dissipative structures. They are all physical structures whose default tendency is to dissipate or fall apart, in accordance with the entropy law.

Our standard of living is roughly measured by the ratio of outside-skin to inside-skin capital—that is, the ratio of human-made artifacts to human bodies, the ratio of one kind of dissipative structure to another kind. Within-skin capital is made and maintained overwhelmingly from renewable resources, while outside-skin capital relies heavily on nonrenewable resources. The rate of evolutionary change of endosomatic organs is exceedingly slow; the rate of change of exosomatic organs has become very rapid. In fact, the evolution of human beings is now overwhelmingly centered on exosomatic organs. This evolution is goal-directed, not random, and its driving purpose has become “economic growth,” and that growth has been achieved largely by the depletion of non-renewable resources.

Although human evolution is now decidedly purpose-driven, we continue to be enthralled by the neo-Darwinist aversion to teleology and devotion to random. Economic growth, by promising “more for everyone eventually,” becomes the de facto purpose, the social glue that keeps things from falling apart. What happens when growth becomes uneconomic, increasing costs faster than benefits? How do we know that this is not already the case? If one asks such questions one is told to talk about something else, like space colonies on Mars, or unlimited energy from cold fusion, or geo-engineering, or the wonders of globalization, and to remember that all these glorious purposes require growth now in order to provide still more growth in the future. Growth is good, end of discussion, now shut up!

Let us reconsider, in the light of these facts, the idea of demographic transition. By definition, this is the transition from a human population maintained by high birth rates equal to high death rates, to one maintained by low birth rates equal to low death rates, and consequently from a population with low life expectancy to one with high life expectancy. Statistically, such transitions have been observed as the standard of living (ratio of exosomatic to endosomatic capital) increases. Many studies have attempted to explain this fact, and much hope has been invested in it as an automatic cure for overpopulation. “Development is the best contraceptive” is a related slogan, partly based in fact, and partly in wishful thinking.

There are a couple of thoughts I’d like to add to the discussion of demographic transition. The first and most obvious one is that populations of artifacts can undergo an analogous transition from high rates of production and depreciation to low ones. The lower rates will maintain a constant population of longer-lived, more durable artifacts.

Our economy has a growth-oriented focus on maximizing production flows (birth rates of artifacts) that keeps us in the pre-transition mode, giving rise to growing artifact populations, low product lifetimes, high GDP, and high throughput, with consequent environmental destruction. The transition from a high-maintenance throughput to a low one applies to both human and artifact populations independently. From an environmental perspective, lower throughput is desirable in both cases, at least up to some distant limit.

The second thought I would like to add to the discussion of demographic transition is a question: Does the human transition when induced by rising standard of living, as usually assumed, increase or decrease the total load of all dissipative structures on the environment? Specifically, if Indian fertility is to fall to the Swedish level, must Indian per capita possession of artifacts (standard of living) rise to the Swedish level? If so, would this not likely increase the total load of all dissipative structures on the Indian environment, perhaps beyond the capacity to sustain the required throughput?

The point of this speculation is to suggest that “solving” the population problem by relying on the demographic transition to lower birth rates could impose a larger burden on the environment rather than the smaller burden that would be the case with a direct reduction in fertility. Of course reduction in fertility by automatic correlation with a rising standard of living is politically easy, while direct fertility reduction is politically difficult. But what is politically easy may be environmentally destructive.

A solution to the populations problems by relying on the demographic transition to lower birth rates could put more strain on our environment. (Image: CC0, Credit: Free-Photos).

To put it another way, consider the I = PAT formula. P, the population of human bodies, is one set of dissipative structures. A, affluence, or GDP per capita, reflects another set of dissipative structures—cars, buildings, ships, toasters, iPads, cell phones, etc. (not to mention populations of livestock and agricultural plants). In a finite world, some populations grow at the expense of others. Cars and humans are now competing for land, water, and sunlight to grow either food or fuel. More nonhuman dissipative structures will at some point force a reduction in other dissipative structures, namely human bodies. This forced demographic transition is less optimistic than the voluntary one induced by chasing a higher standard of living more effectively with fewer dependents. In an empty world, we saw the trade-off between artifacts and people as induced by the desire for a higher standard of living. In the full world, that trade-off seems forced by competition for limited resources.

The usual counter to such thoughts is that we can improve the efficiency by which throughput maintains dissipative structures —technology, T in the formula, measured as throughput per unit of GDP. For example, a car that lasts longer and gets better mileage is still a dissipative structure but with a more efficient metabolism that allows it to live on a lower rate of throughput.

Likewise, human organisms might be genetically redesigned to require less food, air, and water. Indeed smaller people would be the simplest way of increasing metabolic efficiency (measured as the number of people maintained by a given resource throughput). To my knowledge, no one has yet suggested breeding smaller people as a way to avoid limiting births, but that probably just reflects my ignorance. We have, however, been busy breeding and genetically engineering larger and faster-growing plants and livestock. So far, the latter dissipative structures have been complementary with populations of human bodies, but in a finite and full world, the relationship will soon become competitive.

Indeed, if we think of population as the cumulative number of people ever to live over time, then many artifact populations are already competitive with the human population. That is, more consumption today of terrestrial low entropy in non-vital uses (Cadillacs, rockets, weapons) means less terrestrial low entropy available for capturing solar energy tomorrow (plows, solar collectors, ecosystem regeneration). The solar energy that will still fall on the earth for millions of years after the material structures needed to capture it are dissipated, will be wasted, just like the solar energy that shines on the moon.

There is a limit to how many dissipative structures the ecosphere can sustain—more endosomatic capital must ultimately displace some exosomatic capital and vice versa. Some of our exosomatic capital is critical—for example, that part which can photosynthesize, the green plants. Our endosomatic capital cannot long endure without the critical exosomatic capital of green plants (along with soil and water, and of course sunlight). In sum, demographers’ interest should extend to the populations of all dissipative structures, their metabolic throughputs, and the relations of complementarity and substitutability among them. Economists should analyze the supply, demand, production, and consumption of all these populations within an ecosphere that is finite, non-growing, entropic, and open only to a fixed flow of solar energy. This reflects a paradigm shift from the empty-world vision to the full-world vision—a world full of human-made dissipative structures that both depend upon and displace natural structures. Growth looks very different depending on from which paradigm it is viewed.

The carrying capacity of the ecosystem depends on how many dissipative structures of all kinds have to be carried. Some will say to others, “[y]ou can’t have a glass of wine and piece of meat for dinner because I need the grain required by your fine diet to feed my three hungry children.” The answer will be, “[y]ou can’t have three children at the expense of my and my one child’s already modest standard of living.” Both have a good point. That conflict will be difficult to resolve, but we are not yet there.

Rather, now some are saying, “[y]ou can’t have three houses and fly all over the world twice a year because I need the resources to feed my eight children.” And the current reply is, “[y]ou can’t have eight children at the expense of my small family’s luxurious standard of living.” In the second case, neither side elicits much sympathy, and there is great room for compromise to limit both excessive population and per capita consumption. Better to face limits to both human and artifact populations before the terms of the trade-off get too harsh.

Herman Daly is CASSE Chief Economist, Professor Emeritus (University of Maryland), and past World Bank senior economist.

Herman Daly is CASSE Chief Economist, Professor Emeritus (University of Maryland), and past World Bank senior economist.

The problem is of course that our economic system is set up in such a way that it is impossible for the economy to stop growing. In my opinion, it is too weak to say that “our economy has a growth-oriented focus”, instead growth is built into the system, in which money is created as credit by banks through “fractional reserve banking”, and must be paid back with interest. In the absence of economic growth, credits cannot be paid back, causing the collapse of the banking system, along with the value of money, savings and pensions, and eventually entire governments. Even a slow-down of economic growth often causes mass unemployment. No wonder that the Fed and the European Central Bank desperately inject fresh money into the system, in order to restart economic growth.

In short, if one accepts that it is impossible for our economy to keep growing indefinitely, but also impossible to stop growing, then the only ways out are economic/ecological collapse or an alternative economic system. Unfortunately, no one is directly in charge of the economy and in a position to introduce an alternative economic system. And there are not even economic systems that could be suitable. Only Soviet-style communist central planning and Chinese-style state capitalism have been tried on a large scale, and the results are not encouraging for a transition to a steady-state economy. Ecological economics, as I understand it, is a system for analysing the economy, not for running the economy. Maybe something useful could come from think tanks like the New Economics Foundation, but even then the political problem is how to convince the “advanced economies” to adopt it, and how to handle the transition from the current system without destroying savings and pension claims.

Two points to elaborate on Herman’s argument.

First, the IPAT approach is based on accounting equation that cannot be used to test hypotheses; the relationships are assumed true and P, A and T are assumed to have unit elasticity. The STIRPAT approach keeps the mutiplicative logic of IPAT but allows for hypothesis testing and estimation of effects. The general conclusion from several dozen papers in the peer reviewed literature is that the elasticity of P tends to be greater than 1 but less that 2. See http://www.stirpat.org or just search the scholarly web on ‘STIRPAT.”

Second, contemporary demography suggests that it is not just a increase in affluence that reduces fertility but much more an increase in women’s life chances and economic opportunities, access to birth control and reduced infant mortality.

I once wrote an article on reducing the size of human beings as a solution to growth problems. I speculated for example that if we were about half our current size we could split each floor of every building into two, doubling space efficiency, halving energy needs etc. The date of that article was April1.

Continue to enjoy everything Mr. Daly writes.

Making the transition from our current, blatantly unsustainable, system to one which is viable in the

long term requires a paradigm shift in popular thinking if it is to be managed without blood and

tears. I wish I knew how this could be achieved.

Otherwise change will likely happen spontaneously via economic collapse – no longer a distant

possibility – leading to traumatic change and a spontaneous return to local steady-state

economies.

In the latter scenario the human population would have been reduced via an ugly mixture of wars,

starvation and disease.

Ladies and gentlemen:

While Daly brings fancy words and scientific reality to the human overpopulation equation, as a 6 continent world traveler, I personally witnessed what we all face: human misery, human die-off, environmental destruction, dead oceans, polar ice caps melting and species extinctions on a scale unknown since the meteor hit to kill of the big beasts. As Dr. Jack Alpert says, we either need to get our human numbers gracefully diminished, or Mother Nature will do it for us. http://www.skil.org And, she always bats last and rather brutally. We need to push letters and inquiries to [email protected] , Neal Conan at [email protected] , Diane Sawyer, Matt Lauer, 60 Minutes and every other news outlet to get this discussion into the open and on the front burner. Frosty Wooldridge, http://www.frostywooldridge.com

The core of a sustainable economy will be built arround three generations [extended family ] living together with grandparenting skills taking precedence over parenting skills freeing up the middle generation to be active in communiy life

Old people will live on ground floors in multi geerational housing with fewer posessions and share meals and wisdom with second and third generations in peninsular kitchen diners

Most waste is produced by people whos unsetled hearts are restless seeking an external solution/substitute to the love not experienced in their families

like I have been saying for a long time: too much red on the planet now and not enough green (too much meat (is that not what we are?) and not enough plants)

I totally agree that depending on the demographic transition to ensure we do not suffer the effects of overpopulation, is ridiculous. I agree with the general slant of this article. However, it was a very long way of saying something pretty basic. On a finite planet too many people will cause poverty. This is not rocket science. Everyone understands the misery of being in a place that is not big enough for all the people trying to fit in. If indeed, the demographic transition is illustrating some cool mechanism that ensures we do not over breed, that mechanism must be a non-linear curve. If more wealth will cause the birth rate to be lower, and also too much birth rate causes poverty, then there is a trap. We could be stuck on the wrong side of the curve.

There is no such mechanism. The only mechanisms are the obvious ones. Too many people cause poverty, and when people can afford and do use birth control, the birth rate is lower than it otherwise would have been. There simply is no magical mechanism somehow driven by wealth, or women’s education or whatever, that prevents us from over breeding and therefore nothing to prevent us from suffering the effects of overpopulation. We have no choice, we must control our births. There certainly are mechanisms, like starvation and malnutrition, that lower the fertility, but these all are invoked after we have too many. Nothing sends a signal to us humans to stop breeding so that we don’t hit the limits of how many can be provided for.

The I = PAT formula is bogus. It is useless for scientific purposes, and if it is designed to educate people regarding how we should behave, it stinks. There are no units for I, A, and T so scientists should ignore this junk. It obfuscates the real message that should be delivered. Buried inside P is an exponential function. How many children we average determines how fast P is attempting to grow. No amount of A or T can overcome this. No amount of conservation or technologically fueled efficiency gains can overcome the fact that if we average more than 2 children, our numbers are attempting to grow to infinity, and do so at an exponential rate. The finite nature of our planet, stops that growth, and that information is hidden inside P. In short, the only factor that must be measured and controlled is how many children we average. If we average more than 2, we are attempting to grow our numbers to infinity, and our finite planet has no choice but to kill children at exactly the rate over 2 that we are averaging. In other words, the death rate of children must be (x-2)x where x is how many children we average over the long term on a planet of finite size. Think about that. The death rate is determined by how many children we average. Yes, children die because we over breed.

The assumption that our planet was not full of humans in the past, but is filling up, is bogus. Pick some period in history when the human population was stable. Why was it not growing exponentially? The standard answer is that deaths were occurring so fast that we barely made enough babies to keep up. This is ridiculous. The planet was full. Sure, more people could have fit if they knew how to dig up oil, make fertilizer, make internal combustion engines, and refrigerators, but they didn’t know how. Yes, more people did fit in, but that only means that the limit has not yet been an absolute roof. The limits change. The limit where use use fertilizer is higher than if we don’t. There is a higher limit if we do farming vs hunter gathering. There is a limit somewhere north of 7 billion if we burn oil, and much lower if we don’t, and it will run out. All during human history, humans produced babies faster than necessary. Humans were constantly driving our numbers against the limits. This point is vital, it means that we were, and still are, creating babies too fast. Failure to limit our births caused, and causes, children to die.

This means that “You can’t have three children at the expense of my and my one child’s already modest standard of living.” is the wrong response. Consumption is irrelevant. No amount of “modest living” will prevent the suffering that must happen if we average too many children. If it is OK for me to have 3 children, then it is OK for my children to do the same. If that is the case, our number attempt to grow to infinity. Therefore, it is NOT OK for me to have 3 children. The correct response is more like: “It is OK if you have 3 children, as long as your children limit themselves collectively to 4 grandchildren for you.”

This generation is not capable of feeding our numbers without consuming resources faster than they renew. Collectively the world population does not know how to feed our numbers without screwing future generation’s ability to feed this number of people. This means that we must reduce our numbers, and that means we must average fewer than 2, and that means you, me, your children, my children, and Bill and Melinda Gates’ children must stop at one. If some future generation is capable of feeding their numbers without consuming resources faster than they renew, they do not need to reduce their numbers.

An updated version of the inhumane and barbarous feudalist system. The self appointed social darwinist aristocracy created the problem. Are you confused oh all you phd’s. Let me grade school it for you slow indoctrinated minds: The bigger the host, the bigger, sleeker, and fatter the parasite. But now the parasite believes it no longer needs the host and pines for the olden days of the little people who lived briefly and owned nothing. Of course we need a different marketing campaign to sell it this time around. You want a solution you self congratulatory schooled lads? Global enlightenment. This way the power will be forever removed out of the hands of the elitist technocracy and the magic will be revealed to be nothing more than a carnival side show shell game – poorly done at that. The world the parasites created nevertheless is in its death throes and nothing they can do will reverse it. As they say: he who digs a pit ( for his fellow to fall in) will himself fall in it.

I should have learned by now that irony and reductio ad absurdum are lost on humorless ideologues. Just for the record, I do not really advocate breeding smaller people. I was sarcastically suggesting that people who refuse to limit births will need to consider that ridiculous alternative. “Cold Reality” should thaw out a bit.

Why dont you let people live? who are you to tell people to have less babies, this isnt China and were not your cattle banker guy. I know how to make the earth healthier, get rid of Banks, the real cancer on our world.

Thank you for Mr Daly for the broad succinct overview expressed in your article

How can hapiness be equated with a sustainability that can be freely entered into rather than forced by necessity , that seems to be the question

Our culture based on Hellenism [ the external] is self evidently adolescant and better described as adultlessense having matured in a showy sense externally but not internally

Hellenism emphasized the individual,its statues abound ,it provided no family statues yet the family is the university of love with secrets learned by the old conveyed to the young at the oportune moment

Hellenism denies the family by affirming the primacy of the individual ,grand parents are dumped in care homes after being abandoned in isolation from family till incuring premature dementia and no longer able care for themselves they take their secrets with them .

Then likewise perfectly usable furniture is dumped because it is not streamlined enough to satisfy hellenistic cravings of an external perfection that has less utility than what it replaces

Now Hellenism itself is heading for the care home kicking and screaming “why me ,im not deluded”

Hellenism was the first sign of dementia as far as “exosomatic” development was concerned ,but no one noticed ,except the religious thinkers

cont

Why is hellenic development ultimately so destructive?

Hellenism developed from europe with its origins probably in hunting and associated canibalism

ie A failed hunt and a dead or injured hunter that could not be carried by the other hungry hunters

I] the dead hunter gets eaten hunt goes on

2]The injured dying hunter gets clubbed [why wait] and eaten, hunt goes on

3]The slowest hunter gets eaten, hunt goes on

4]The remainder draw straws [decimation] hunt goes on

Hunting groups fight and eat eachother

Military cooperative skills developed

Technology developed for military purpose first

To repair military equipment and finance technological military development transformer economy developed alongside using fractional reserve banking ,which also pays the subjugated for their goods

Expanding hegenomy pays interest to sustain the illusion of fiat value

Economy/hegenomy stops expanding due to expansion induced resource depletion

Low resource use service industries spring up to absorb fiat [cobblers ,stand up comedians, chinese restaurants , lesbian guidance cuncillors]

Resourse consumptive military equipment rusts breaks down becomes obsolete and out moded

Politicians decide to declare war on weakest [here we go again]

No proper military equipment left to engage enemy

Stand up comedians sent into battle first [followed by the hungry rest]

To prove that “satire is the greatest martial art” and slay the enemy with the breath of their mouth

Garlic provided by the chinese restaurants

Hellenism does not prepare for old age

You should read less of whatever you’ve been reading, and more G.K. Chesterton.

On my posting above the formula for the childhood death rate should be (x-2)/x. The / is missing.

The world is already inundated with a population of small people they are known as children and with proper parenting skills they will grow into mature self limiting adults ,at present we grow older and still wish to get bigger because we have not grown up wiser .

Populations of fewer artifacts could be created by synthesizing boilers, washing machines,tumble driers , fridges ,dehumidifiers ,irons ,cooker hoods etc into one combined unit that utilizes the surplus of one process be it hot, cold, or damp or dry to drive another. thus reducing the overall unit population and energy consumption

Storage tank cold water could be used to dehumidify and cool internal summer heat whilst in the process being preheated before it becomes temperature boosted in the hot water storage cylinders by the surplus heat from air conditioning compressors

The water being used for bathing could be temporarily stored or simply left in the bath overnight till its heat is disipated internally [in winter] and then used for flushing toilets, watering the garden jet washing etc

Unfortunately corporate interest profits thrive on the waste of inherrited energy wealth which then drives its price even higher and their enormous financial clout allows them to buy the patents on products that would be more energy efficient

patents should not be allowed on technological invention not brought to market at an affordable price to serve the public interest

Double glazing drives condensation [due to lack of ventilation once provide by draughts in ill fitting widows and doors] onto external walls behind cupboards makeing electric dehumidifiers necessary

Why not leave one small window in the coolest part of the house facing away from the sun as a single glazed therefore surface cooler unit to attract condensate with a built in drain off to external cill

Amazing page i really enjoy scanning your postѕ,

keep up thhe great work!