An Economics Fit for Purpose in a Finite World

by Herman Daly

Causation is both bottom-up and top-down: material cause from the bottom and final cause from the top, as Aristotle might say. Economics, or as I prefer, “political economy,” is in between and serves to balance desirability (the lure of right purpose) with possibility (the constraints of finitude). We need an economics fit for purpose in a finite and entropic world.

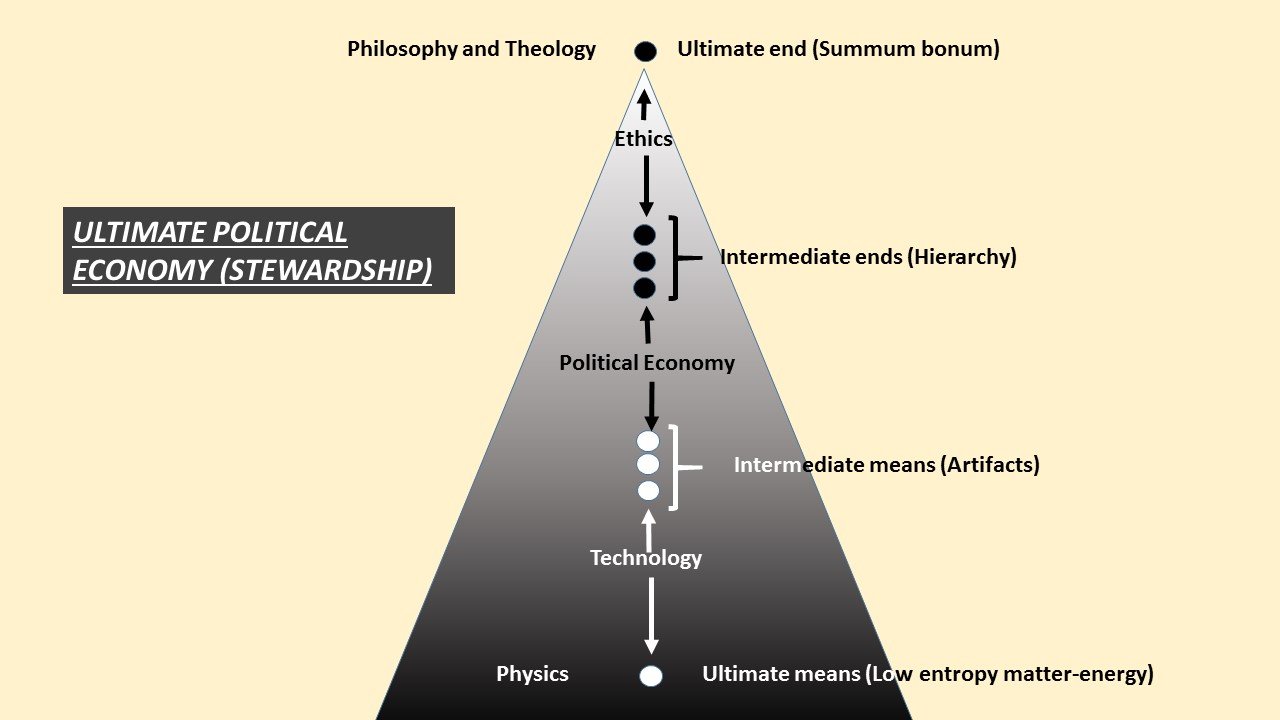

As a way to envision such an inclusive economics, consider the “ends-means pyramid” shown below. At the base of the pyramid are our ultimate means, low entropy matter-energy—that which we require to satisfy our purposes—which we cannot make but only use up. We use these ultimate means, guided by technology, to produce intermediate means (artifacts, commodities, services, etc.) that directly satisfy our needs. These intermediate means are allocated by the political economy to serve our intermediate ends (health, comfort, education, etc.), which are ranked ethically in a hierarchy by how strongly they contribute to our best perception of the Ultimate End. We can see the Ultimate End only dimly and vaguely, but in order to ethically rank our intermediate ends, we must compare them to some ultimate criterion. We cannot avoid philosophical and theological inquiry into the Ultimate End just because it is difficult. To prioritize logically requires that something must go in the first place.

The Ends-Means Pyramid

The ends-means pyramid or spectrum relates the basic physical precondition for usefulness (low entropy matter-energy) through technology, political economy, and ethics, to the service of the Ultimate End, dimly perceived but logically necessary. The goal is to unite the material of this world with our best vision of the good. Neoclassical economics, in neglecting the Ultimate End and ethics, has been too materialistic; in also neglecting ultimate means and technology, it has not been materialistic enough.

The middle position of economics is significant. Economics in its modern form deals with the allocation of given means to satisfy given ends. It takes the technological problem of converting ultimate means into intermediate means as solved. Likewise, it takes the ethical problem of ranking intermediate ends with reference to a vision of the Ultimate End as also solved. So all economics has to do is efficiently allocate given means among a given hierarchy of ends. That is important, but not the whole problem. Scarcity dictates that not all intermediate ends can be attained, so a ranking is necessary for efficiency—to avoid wasting resources by satisfying lower ranked ends while leaving the higher ranked unsatisfied.

Ultimate political economy (stewardship) is the total problem of using ultimate means to best serve the Ultimate End, no longer taking technology and ethics as given, but as steps in the total problem to be solved. The total problem is too big to be tackled without breaking it down into its pieces. But without a vision of the total problem, the pieces do not add up or fit together.

The dark base of the pyramid is meant to represent the fact that we have a relatively solid knowledge of our ultimate means, various sources of low entropy matter-energy. The light apex of the pyramid represents the fact that our knowledge of the Ultimate End is much less clear. The single apex will annoy pluralists who think that there are many “ultimate ends.” Grammatically and logically, however, “ultimate” requires the singular. Yet there is certainly room for plural perceptions of the nature of the singular Ultimate End, and much need for tolerance and patience in reasoning together about it. However, such reasoning together is short-circuited by a facile pluralism that avoids ethical ranking of ends by declaring them to be “equally ultimate.”

It is often the concrete bottom-up struggle to rank particular ends that gives us a clue or insight into what the Ultimate End must be to justify our proposed ranking.

As a starting point in that reasoning together, I suggest the proposition that the Ultimate End, whatever else it may be, cannot be growth in GDP! A better starting point for reasoning together is John Ruskin’s aphorism that “there is no wealth but life.” How might that insight be restated as an economic policy goal? For initiating discussion, I suggest “maximizing the cumulative number of lives ever to be lived over time at a level of per capita wealth sufficient for a good life.” This leaves open the traditional ethical question of what is a good life while conditioning its answer to the realities of economics and ecology. At a minimum, it seems a more convincing approximation to the Ultimate End than today’s impossible goal of “ever more things for ever more people forever.”

Herman Daly is CASSE Chief Economist, Professor Emeritus (University of Maryland), and past World Bank senior economist.

Herman Daly is CASSE Chief Economist, Professor Emeritus (University of Maryland), and past World Bank senior economist.

Succinctly put! The question you lead me (and hopefully others) to is How does the general public interact with this and fit it into every day life? Too easily we focus on immediate goals, needs that are real or perceived, and forego the sort of long-term view necessary to reach our ultimate end-goal (presumably a life that we’ve enjoyed and are satisfied with).

Once again – excellent overview – bottom to top (or vice-versa)

Thank you so much, Prof. Daly! Your stuff needs a much wider audience – so how to get it …

I will forward this to a site, Common Dreams, that has what i think might be a receptive audience and spread it where I can …..

Aquifer is right; the content need to be brought to as large an audience as possible. After all, it is approaching the concept of Planetheonomics! That still being too uncomfortable at least humanity – before it is too late – needs to welcome and embellish the very rational concept of science-based Ecological Economics.

“Yet there is certainly room for plural perceptions of the nature of the singular Ultimate End, and much need for tolerance and patience in reasoning together about it.”

For sure and to that end I recommend Larry L. Rasmussen’s new book Earth-Honoring Faith: Religious Ethics in a New Key. (Reinhold Niebuhr Professor Emeritus of Social Ethics, Union Theological Seminary, New York City.) The breadth, depth and inclusiveness of his thought and research is astounding.

Very interesting, as always! I kind of wish you went into a bit more detail about this elusive “ultimate end” though. Do you mean happiness and life satisfaction? Or perhaps some kind of spiritual growth or philosophical enlightenment, as according to each person’s faith? I would assume the “point” of life is a personal matter for each individual, but the way you capitalised the term implies you do have something in mind! As you say though, I think we can all agree such an “ultimate” end would not be anything to do with GDP, which would struggle to even make the cut of “intermediate end”.

Thanks for the article (:

Prof. Daly suggests that the Ultimate End (aka purpose, highest good or final cause) has “downward” causal power with some capacity to influence the selection of intermediate ends.

An ethical fog, however, separates intermediate ends from the Ultimate End because we can perceive the highest good only “dimly and vaguely.”

If economic goal-setting and policy-making are to be informed by the Ultimate End, then we need to know how to penetrate that fog. One way to do this is to speculate about values which may be consistent with the highest good, then operationalize those values in the form of clear economic prescriptions. Daly starts with the aphorism “There is no wealth but life” which asserts life itself as the basic building block of that which is good. Maximizing life, consistent with principles of fairness and ecological integrity, is the prescription that follows.

Opinions differ about the Ultimate End – whether it exists, what purpose or values may be inherent to it, how downward causation works, and so forth – because we don’t have direct access to it. So it seems we may be stuck with the speculative, inductive approach to reconciling Purpose with economic behavior that Daly suggests. I’m not sure that’s true, but I’ll follow along anyway with a speculative observation which may have economic policy implications:

Economic activity is essentially amoral; it’s the sum total of mechanical transactions between consenting parties. Consistently moral economic outcomes, therefore, require socio-political oversight informed by reason and ethics. The purpose of the economy is to serve community efficiently. The Purpose of community is to serve/be compatible with the Ultimate End.

In practical terms, this suggests that market forces should be tailored as necessary to suit the needs of community, where “community” may be understood to comprise individuals singly and collectively attempting to navigate the ethical divide between intermediate and Ultimate ends.

There are large issues and challenges at play here, but little to lose by exploration.

I believe there should be the right sort of growth if the human race is going to survive. Here, I am implying so-called “green growth.” My evolving project will throw some light on all this. It is called Transfinancial Economics.

An essential and quite urgent conversation to have: how to define good life. Can CASSE and you professor Daly, help us with specifics? We also need a benchmark country to build the ideal good life from there. Denmark maybe? They seem to be the happiest people in a most developed country.

Here is an example:

1. Healthcare (undisputed public good)- universal

2. Education (undisputed public good at all levels) – free and open to all

3. Meaningful, dignified work for all

4. Income range $70000 – $500000

5. Workweek: flexible, proportional with productivity and focused on needs, rather than wants, around 3 days at present (my guess)

6. Housing: ~ xxx sqft (for zero GHG emissions)

7. Transportation – public and mass affordable and available for all

8. Urban design for living within one planet footprint

9. Advanced technology: e.g. solar supersonic airplanes (in other words we should not give up sophisticated life for good life)

Interesting essay, as usual.

Many decades ago I was an engineer at the GM Tech Center. I remember lunchtime conversation on the subject of “How much money does a man (sic) need to earn to live well.” Very quickly it got into what makes up a good life. Consensus: 3-BR house in a suburb with good schools; a new car every four years (cars did not hold up well back then); good food, including occasional luxuries (there was little overweight, virtually no obesity among these engineers); enough for reasonable hobbies (almost every engineer was an avid photographer); a decent vacation every other year; sending 2 or 3 kids to the University of Michigan. Mid-1970’s (just before the oil embargo): $35K/yr. Almost half of us were earning that much.

A cynical observation got plenty of laughs: “If you earn twice this much, you won’t improve your life by doing things you couldn’t do on a lower income. You’d still be doing the same things, but doing them more expensively!”